La Poesia È Una Pipa…»

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(The Avoidance of Everything) Bill Beckley—1968-1978 On

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Albertz Benda Opens with the Inaugural Exhibition The Accidental Poet (The Avoidance of Everything) Bill Beckley—1968-1978 On view September 10 – October 3, 2015 Graphic for Myself as De Kooning’s Stove, 1974 Washington, 1969 Cibachrome and black and white Black and white photograph on photographs 30 x 60 inches (76.2 x paperboard 14 x 28 inches 152.4 cm) Edition of 3 (35.5 x 71 cm) When I did the piece crossing the Delaware River on foot, dripping paint as I went, the current took me under, and I lost not only the paint but also the camera I was using to document the work. I realized then that all I had left was the story. – Bill Beckley, 2007 New York, NY, June 11, 2015 – For its inaugural exhibition, Albertz Benda is pleased to present a solo show of rare, early works by Bill Beckley from 1968-1978, many of which have not been on view in four decades. A fundamental member of the ‘70s SoHo art community, Beckley’s work provides a crucial glimpse into one of the key New York art movements of the 20th century. The Accidental Poet (The Avoidance of Everything) features materials drawn from Beckley’s archives, shuttered since the 1970s, unveiling never before seen performance documentation, watercolors, and studies for his best-known work, among other materials. The exhibition will also feature the artist’s conceptual narrative work of typed fictions and framed photographs, previously shown at landmark exhibitions including the Whitney Biennial, Documenta and the Venice Biennale, which have not been on view in the United States since the 1970s. -

It's Customary for Galleries to Display Their Artists' Newest Works. That Is

Installation view, “The Accidental Poet: Bill Beckley—1968-1978,” 2015, at Albertz Benda. It’s customary for galleries to display their artists’ newest works. That is understandable, for we want to see how these figures are developing; we usually leave it to museums to offer a broader historical perspective. But it can be very instructive, also, to study the origins of a now-celebrated artist. Bill Beckley started showing art in 1968, at the moment when change was in the air in New York. He was one of a group of now- Carrier, David. “Accidentally on Purpose: Bill Beckley at Albertz Benda, Artcritical, October 3, 2015. legendary artists associated with the pioneering Soho Gallery at 112 Greene Street — they included Louise Bourgeois, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark and Dennis Oppenheim. This densely packed exhibition provides a good overview of his first decade of artmaking. “The Accidental Poet” included Myself as Washington (1969), a photograph that anticipates Cindy Sherman’s playful studies of personal identity; and the text with photograph Joke About Elephants (1974), a precursor of Richard Prince’s joke paintings. There is Rooster, Bed, Lying (1971), a bed underneath a chicken wire cage housing the live rooster who was present at the opening. In Photo Document for Song for a Chin-up (1971), which was performed by a tenor at the opening, a tenor sings while doing a chin- up. Artists of the previous generation, the Pop painters and Minimalists, who came of age in the 1960s, defined the unity of their concerns by creating distinctive visual styles — a Warhol, like a Lichtenstein or a Donald Judd, is unmistakably their personal product. -

Press Release

ROGER WELCH: EXHIBITION DATES: Expressions of Memory March 2 – April 24, 2021 WESTWOOD GALLERY NYC presents a solo exhibition by New York artist, Roger Welch, entitled Expressions of Memory. This is his first solo show with the gallery and the first solo show of Welch’s work in fifteen years. The exhibition will be on view March 2 - April 24, 2021. Expressions of Memory highlights twenty works from Roger Welch’s narrative art movement founded in the 1970s, along with artists John Baldessari, William Wegman, and Bill Beckley. The aim of narrative art is to tell a sequential story, often based on personal memories. Welch works in a variety of media including sculpture, photography, video, painting, and performance. This exhibition features four main bodies of work produced from the 1970s through the 1990s: the autobiographic ‘Welch Family’ series, ‘Woven Narratives’ series, ‘Photo Perception’ series, and ‘Austin, Texas Children’ series. Included in the exhibition is a video installation, “Welch”, 16mm motion picture with sound, 1:27:00, first exhibited in 1972 at the Ileana Sonnabend Gallery in SoHo. The film was edited from family home movies dating back to 1927, to show the cyclical nature of a middle-class family in the suburbs, overlaid with Welch’s own recollections of his family’s life through his relatives’ stories. Coupled with the video are photo diptychs and triptychs utilizing vintage photographs sourced from his family’s archive with participatory hand scripted memories of events by his father, mother, grandfather, and grandmother. The shared memories exemplify the quest of a middle-class family in pursuit of the American Dream in the 1970s as they operated their paint and wallpaper shop in Westfield, New Jersey, family-owned for over three generations. -

Press Luciano Fabro Frieze, April 1, 2008

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Luciano Fabro By Andrew Bonacina (April 1, 2008) The word ‘Ricomincerò!’ (I will start again) was poignantly inscribed at the entrance to ‘Luciano Fabro: Didactica magna, Minima moralia’. Punctuating the end of an energetic, manifesto-like statement by the artist railing against the ‘reduction of the work to the status of an advertising gimmick’, this personal call to arms could not help but be read as Fabro’s unintentional last will and testament in the wake of his death in June 2007, during preparations for the exhibition. These potent last words revealed an undiminished ethical stance toward the value of a work of art: a stance that fuelled the artist’s creation of a remarkable oeuvre spanning almost six decades. Inevitably, Fabro’s untimely death burdened this exhibition with expectations of a broad and exhaustive survey, yet his adamant desire to focus solely on early works produced between 1963 and 1968 was fully acknowledged by curators Rudi Fuchs, Eduardo Cicelyn and Silvia Fabro, the artist’s daughter, who realized this coolly austere exhibition according to Fabro’s detailed notes and plans. The exhibition’s cut-off date somewhat pointedly marked the moment Fabro became associated with the Arte Povera movement, which reflected a period of intense social and political change in Italy, characterized by strong anti-war sentiment, scepticism of new technology and a growing hatred of the rampant ‘Americanization’ of culture. Arte Povera embodied an art of protest, an art which, wrote Germano Celant in Arte Povera in 1967, consisted in ‘taking away, eliminating, downgrading things to a minimum, impoverishing signs to reduce them to archetypes’. -

On Benjamin Patterson Julia Elizabeth Neal Bull Shit No

all–over # 11 On Benjamin Patterson Julia Elizabeth Neal Bull Shit No. 2 and the Life of An Interview Autorin: Julia Elizabeth Neal Erschienen in : all-over 11, Herbst 2016 Publikationsdatum : 2. Dezember 2016 URL : http://allover-magazin.com/?p=2509 ISSN 2235-1604 Quellennachweis : Julia Elizabeth Neal, On Benjamin Patterson, Bull Shit No. 2 and the Life of An Interview, in : all-over 11, Herbst 2016, URL : http://allover-magazin.com/?p=2509. Verwendete Texte, Fotos und grafische Gestaltung sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Eine kommerzielle Nutzung der Texte und Abbildungen – auch auszugsweise – ist ohne die vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung der Urheber oder Urheberinnen nicht erlaubt. Für den wissenschaftlichen Gebrauch der Inhalte empfehlen wir, sich an die vorgeschlagene Zitationsweise zu halten, mindestens müssen aber Autor oder Autorin, Titel des Aufsatzes, Titel des Magazins und Permalink des Aufsatzes angeführt werden. © 2016 all-over | Magazin für Kunst und Ästhetik, Wien / Basel all–over # 11 On Benjamin Patterson Julia Neal Bull Shit No. 2 and the Life of An Interview Benjamin Patterson, who saw over fifty years of experimental art production as a Fluxus co-founder and artist, passed away this summer. Born in Pittsburgh May 29, 1934, Patterson was an Afri- can-American bassist with limited professional opportunities in segregation-era United States. Instead, Patterson circumvented ex- isting racial barriers by relocating to Canada and performing with symphony orchestras, at which point he took closer interest in elec- tronic music.1 A trip to Germany redirected the course of his career to experimental art production after a negative encounter with ac- claimed Karlheinz Stockhausen. -

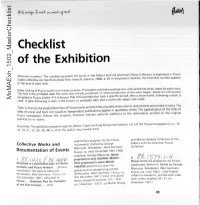

Checklist of the Exhibition

Checklist of the Exhibition Silverman numbers. The numbering system for works in the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection is explained in Fluxus Codex, edited by Jon Hendricks (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), p. 29.ln the present checklist, the Silverman number appears at the end of each item. Dates: Dating of Fluxus works is an inexact science. The system used here employs two, and sometimes three, dates for each work. The first is the probable date the work was initially produced, or when production of the work began. based on information compiled in Fluxus Codex. If it is known that initial production took a specific period, then a second date, following a dash, is MoMAExh_1502_MasterChecklist used. A date following a slash is the known or probable date that a particular object was made. Titles. In this list, the established titles of Fluxus works and the titles of publications, events, and concerts are printed in italics. The titles of scores and texts not issued as independent publications appear in quotation marks. The capitalization of the titles of Fluxus newspapers follows the originals. Brackets indicate editorial additions to the information printed on the original publication or object. Facsimiles. This exhibition presents reprints (Milan: Flash Art/King Kong International, n.d.) of the Fluxus newspapers (CATS.14- 16, 19,21,22,26,28,44) so that the public may handle them. and Marian Zazeela Collection of The preliminary program for the Fluxus Gilbert and lila Silverman Fluxus Collective Works and movement). [Edited by George Maciunas. Wiesbaden, West Germany: Collection Documentation of Events Fluxus, ca. -

The Politics of Arte Povera

Living Spaces: the Politics of Arte Povera Against a background of new modernities emerging as alternatives to centres of tradition in the Italy of the so-called “economic miracle”, a group formed around the critic Germano Celant (1940) that encapsulated the poetry of arte povera. The chosen name (“poor art”) makes sense in the Italy of 1967, which in a few decades had gone from a development so slow it approached underdevelopment to becoming one of the economic dri- ving forces of Europe. This period saw a number of approaches, both nostalgic and ideological, towards the po- pular, archaic and timeless world associated with the sub-proletariat in the South by, among others, the writer Carlo Levi (1902-1975) and the poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975). the numbers relate to the workers who join a mensa operaia (workers’ table), a place as much to do with alienation as unionist conspiracy. Arte povera has been seen as “a meeting point between returning and progressing, between memory and anti- cipation”, a dynamic that can be clearly understood given the ambiguity of Italy, caught between the weight of a legendary past and the alienation of industrial develo- pment; between history and the future. New acquisitions Alighiero Boetti. Uno, Nove, Sette, Nove, 1979 It was an intellectual setting in which the povera artists embarked on an anti-modern ap- proach to the arts, criticising technology and industrialization, and opposed to minimalism. Michelangelo Pistoletto. It was no coincidence that most of the movement’s members came from cities within the Le trombe del Guidizio, 1968 so-called industrial triangle: Luciano Fabro (1936-2007), Michelangelo Pistoletto (1933) and Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994) from Turin; Mario Merz (1925-2003) from Milan; Giu- lio Paolini (1940) from Genoa. -

Geoffrey Hendricks

Geoffrey Hendricks Geoffrey Hendricks was involved in the Judson Gallery in 1967 and 1968. _ n the 1960s, Judson Memorial Church, and especially the Jud- son Gallery in the basement of Judson House, became an impor- tant part of my life. That space at 239 Thompson Street was modest but versatile. Throughout the decade I witnessed many transformations of it as friends and artists, including myself, created work there. The gallery's small size and roughness were perhaps assets. One could work freely and make it into what it had to be. It was a con- tainer for each person's ideas, dreams, images, actions. Three people in particular formed links for me to the space: Allan Kaprow, Al Carmines, and my brother, Jon Hendricks. It must have been through Allan Kaprow that I first got to know about the Judson Gallery. When I began teaching at Rutgers Univer- sity (called Douglass College at the time) in 1956, Allan and I be- came colleagues, and I went to the Judson Gallery to view his Apple Shrine (November 3D-December24, 1960). In that environment one moved through a maze of walls of crumpled newspaper supported on chicken wire and arrived at a square, flat tray that was suspended in the middle and had apples on it. With counterpoints of city and country, it was dense and messy but had an underlying formal struc- ture. His work of the previous few years had had a tremendous im- pact on me: his 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, at the Reuben Gallery (October 1959), his earlier installation accompanied with a text en- titled Notes on the Creation of a Total Art at the Hansa Gallery (February 1958), and his first happening in Voorhees Chapel at Douglass College (April 1958). -

The Politics of Arte Povera

Living Spaces: the Politics of Arte Povera Against a background of new modernities emerging as alternatives to centres of tradition in the Italy of the so- called “economic miracle”, a group formed around the critic Germano Celant (1940) that encapsulated the po- etry of arte povera. The chosen name (“poor art”) makes sense in the Italy of 1967, which in a few decades had gone from a development so slow it approached underdevelopment to becoming one of the economic driving forces of Europe. This period saw a number of approaches, both nostalgic and ideological, towards the popular, archaic and timeless world associated with the sub-proletariat in the South by, among others, the writer Carlo Levi (1902-1975) and the poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975). Fibonacci Napoli (Fabricca a San Giovan- ni a Teduccio), 1971, a work which pre- sents a numerical sequence that com- plicates and humanizes the simplistic logic of minimalist artists, while adding a political component: the numbers relate to the workers who join a mensa operaia (workers’ table), a place as much to do with alienation as unionist conspiracy. Arte povera has been seen as “a meeting point between returning and progressing, between memory and anticipation”, a dynamic that can be clearly understood given the ambiguity of Italy, caught be- tween the weight of a legendary past and the alienation of industrial development; between history and the future. It was an intellectual setting in which the povera artists embarked on an anti-modern approach to the arts, criticising technology and industrialization, and opposed to min- imalism. -

Fluxus: the Is Gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists Megan Butcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Megan, "Fluxus: The iS gnificant Role of Female Artists" (2018). Honors College Theses. 178. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and early 1970s laid the groundwork for future female artists and performance art as a medium. However, throughout my research, I have found that while there is evidence that female artists played an important role in this art movement, they were often not written about or credited for their contributions. Literature on the subject is also quite limited. Many books and journals only mention the more prominent female artists of Fluxus, leaving the lesser-known female artists difficult to research. The lack of scholarly discussion has led to the inaccurate documentation of the development of Fluxus art and how it influenced later movements. Additionally, the absence of research suggests that female artists’ work was less important and, consequently, keeps their efforts and achievements unknown. It can be demonstrated that works of art created by little-known female artists later influenced more prominent artists, but the original works have gone unacknowledged. -

Luciano Fabro (Turin, 1936 – Milan, 2007) Fabro, One of the Members Of

Luciano Fabro (Turin, 1936 – Milan, 2007) Fabro, one of the members of the Arte Povera group, formulated his early works by examining the relationship between object, body, and space. The forms are basic and geometric, what one might describe as minimalist, but the attitude behind them stems from an idea and from the vitality of movement. They exist within a system that seems conceived to unfold at a meeting point between Leonardo’s Scheme on the Proportions of the Human Body and Palladian architecture. In 1969 he began a long series of works developed around the geographic outline of Italy, and he turned this shape into his personal blank page: “I need to know how my hands function on something that remains static. The form of Italy is static, immobile, and I measure my hands’ mobility against its stillness. Italy is like a sketch album, an aide mémoire that I have continued to do over the years: if I’m working on something new, I sketch it out on one of these Italies.” Speculum Italiae (Italy’s Mirror), 1971, begins with a shape in mirrored glass, tightly wrapped in thin strips of lead, like a mummified body. In Italia all’asta (Italy on Auction), 1994, two Italy shapes, one placed upside-down, are positioned face-to-face and then nailed to a pole; the surface of the shapes has a pattern in relief that is typical of manhole covers. The Italy that is right side up might be raised up on the pole like a proud insignia of our country, but the other one, upside down, instead seems to hang from a gallows, held prisoner by a pin, like a giant insect, captured or fallen dead. -

Fluxus Family Reunion

FLUXUS FAMILY REUNION - Lying down: Nam June Paik; sitting on the floor: Yasunao Tone, Simone Forti; first row: Yoshi Wada, Sara Seagull, Jackson Mac Low, Anne Tardos, Henry Flynt, Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, Peter Moore; second row: Peter Van Riper, Emily Harvey, Larry Miller, Dick Higgins, Carolee Schneemann, Ben Patterson, Jon Hendricks, Francesco Conz. (Behind Peter Moore: Marian Zazeela.) Photo by Josef Astor taken at the Emily Harvey Gallery published in Vanity Fair, July 1993. EHF Collection Fluxus, Concept Art, Mail Art Emily Harvey Foundation 537 Broadway New York, NY 10012 March 7 - March 18, 2017 1PM - 6:30PM or by appointment Opening March 7 - 6pm The second-floor loft at 537 Broadway, the charged site of Fluxus founder George Maciunas’s last New York workspace, and the Grommet Studio, where Jean Dupuy launched a pivotal phase of downtown performance art, became the Emily Harvey Gallery in 1984. Keeping the door open, and the stage lit, at the outset of a new and complex decade, Harvey ensured the continuation of these rare—and rarely profitable—activities in the heart of SoHo. At a time when conventional modes of art (such as expressive painting) returned with a vengeance, and radical practices were especially under threat, the Emily Harvey Gallery became a haven for presenting work, sharing dinners, and the occasional wedding. Harvey encouraged experimental initiatives in poetry, music, dance, performance, and the visual arts. In a short time, several artist diasporas made the gallery a new gravitational center. As a record of its founder’s involvements, the Emily Harvey Foundation Collection features key examples of Fluxus, Concept Art, and Mail Art, extending through the 1970s and 80s.