David Smith's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATHLETICS AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN RECORDS AS at 16Th September 2020

ATHLETICS AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN RECORDS AS AT 16th September 2020. MEN EVENT PERF. DATE VENUE NAME STATE D.O.B. 100 METRES Aust Allcomers 9.87 23-Sep-00 Sydney Maurice Greene USA 23-Jul-74 Aust National 9.93 5-May-03 Mita, JPN Patrick Johnson ACT 26-Sep-72 Aust U20 10.15 1-Jul-18 Finland Jake Doran QLD 18-Jul-00 Aust U18 10.38 11-Dec-15 Perth Jack Hale TAS 22-May-98 Aust U16 10.67 7-Dec-13 Townsville Jordon Shelley NSW 27-Feb-98 200 METRES Aust Allcomers 19.92 25-Feb-99 Melbourne Frankie Fredericks NAM 2-Oct-67 Aust National 20.06 16-Oct-68 Mexico City Peter Norman VIC 15-Jun-42 Aust U20 20.48 3-Feb-85 Brisbane Fred Martin NSW 4-Oct-66 Aust U18 20.90 6-Nov-82 Sydney Darren Clark NSW 6-Sep-65 20.90 19-Aug-89 Saga Paul Greene NSW 9-Dec-72 20.90 24-Sep-17 Townsville Zane Branco QLD 4-Jan-00 Aust U16 21.44 8-Dec-13 Townsville Jordon Shelley NSW 27-Feb-98 400 METRES Aust Allcomers 43.84 25-Sep-00 Sydney Michael Johnson USA 13-Sep-67 Aust National 44.38 26-Sep-88 Seoul Darren Clark NSW 6-Sep-65 Aust U20 44.75 8-Aug-84 Los Angeles Darren Clark NSW 6-Sep-65 Aust U18 45.96 19-Aug-89 Saga Paul Greene NSW 9-Dec-72 Aust U16 47.99 13-Dec-19 Brisbane Jack Boulton VIC 15-Jun-04 800 METRES Aust Allcomers 1:43.15 4-Mar-10 Melbourne David Rudisha KEN 17-Dec-88 Aust National 1:44.21 20-Jul-18 Monaco Joseph Deng VIC 7-Jul-98 Aust U20 1:45.91 28-Jul-95 Lindau Paul Byrne VIC 29-Jan-76 Aust U18 1.47.24 11-Dec-93 Canberra Paul Byrne VIC 29-Jan-76 Aust U16 1:51.41 11-Dec-88 Canberra Mark Holcombe VIC 21-Aug-73 1000 METRES Aust Allcomers 2:17.67 14-Jan-88 Melbourne -

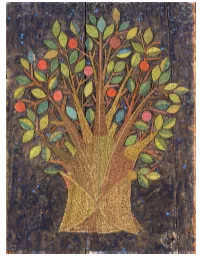

Hudson River at West Point)

Search Collections "True religion shows its influence in every part of our conduct; it is like the sap of a living tree, which penetrates the most distant boughs."--William Penn, 1644-1718. From the series Great Ideas of Western Man. 1961 Vin Giuliani Born: New York 1930 painted wood on wood 23 1/2 x 17 1/2 in. (59.6 x 44.6 cm) Smithsonian American Art Museum Gift of Container Corporation of America 1984.124.106 Not currently on view Keywords Landscape - tree painting metal - nails paint - oil wood wood About Vin Giuliani Born: New York 1930 Search Collections Fields and Flowers ca. 1930-1935 William H. Johnson Born: Florence, South Carolina 1901 Died: Central Islip, New York 1970 watercolor and pencil on paper 14 1/8 x 17 3/4 in. (35.9 x 45.0 cm) Smithsonian American Art Museum Gift of the Harmon Foundation 1967.59.8 Not currently on view About William H. Johnson Born: Florence, South Carolina 1901 Died: Central Islip, New York 1970 More works in the collection by William H. Johnson Online Exhibitions • SAAM :: William H. Johnson • Online Exhibitions / SAAM • Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum • Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum • Cottingham - More to It!: The Whole Story • Cottingham - More to It!: The Whole Story • S C E N E S O F A M E R I C A N L I F E • M O D E R N I S M & A B S T R A C T I O N • Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum • Online Exhibitions / SAAM Classroom Resources • William H. -

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan. 31 – May 31, 2015 Exhibition Checklist DOWN AT CONEY ISLE, 1861-94 1. Sanford Robinson Gifford The Beach at Coney Island, 1866 Oil on canvas 10 x 20 inches Courtesy of Jonathan Boos 2. Francis Augustus Silva Schooner "Progress" Wrecked at Coney Island, July 4, 1874, 1875 Oil on canvas 20 x 38 1/4 inches Manoogian Collection, Michigan 3. John Mackie Falconer Coney Island Huts, 1879 Oil on paper board 9 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches Brooklyn Historical Society, M1974.167 4. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene, c. 1879 Oil on canvas 12 x 20 inches Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Bequest of Annie Swan Coburn (Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn), 1934:3-10 5. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene with Acrobats, c. 1879-81 Oil on canvas 6 x 9 inches Collection Max N. Berry, Washington, D.C. 6. William Merritt Chase At the Shore, c. 1884 Oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 34 1/4 inches Private Collection Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Page 1 of 19 Exhibition Checklist, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861 – 2008 12-15-14-ay 7. John Henry Twachtman Dunes Back of Coney Island, c. 1880 Oil on canvas 13 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 1956.010 8. William Merritt Chase Landscape, near Coney Island, c. 1886 Oil on panel 8 1/8 x 12 5/8 inches The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, N.Y., Gift of Mary H. Beeman to the Pruyn Family Collection, 1995.12.7 9. -

Online Exhibition David Smith. Sprays

Press Release Online Exhibition David Smith. Sprays hauserwirth.com Live Date: 7 July 2020 Hauser & Wirth announces an online exhibition featuring the late post-war American artist David Smith (1906- 1965), including six virtual museum loans alongside significant works spanning from 1958 until 1964. ‘David Smith. Sprays’ is curated by the artist’s daughters and co-presidents of the David Smith Estate, Candida and Rebecca Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Field, Executive Director of the David Smith Estate. The pioneering body of work is presented with walkthrough films of the virtual exhibition space created in HWVR. With thanks to contributing museums: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Harvard Art Museums/ Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC; Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/de Young Museum, San Francisco; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. ‘I belong with painters, in a sense; and all my early friends were painters because we all studied together. And I never conceived of myself as anything other than a painter because my work came right through the raised surface and color and objects applied to the surface’. – David Smith, 1960 The in-depth digital presentation celebrates Smith's innovative approach to the newly available medium of aerosol paint and the consequent interplay between colour, form and the drawn image. The Sprays represent a direct and unmediated form of expression that provide a vital counterpoint to Smith’s metal work. When creating a sculpture, Smith would often place components of the work in progress on white-washed areas of his shop floor, before joining them together. -

College of Fine and Applied Arts Annual Meeting 5:00P.M.; Tuesday, April 5, 2011 Temple Buell Architecture Gallery, Architecture Building

COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS ANNUAL MEETING 5:00P.M.; TUESDAY, APRIL 5, 2011 TEMPLE BUELL ARCHITECTURE GALLERY, ARCHITECTURE BUILDING AGENDA 1. Welcome: Robert Graves, Dean 2. Approval of April 5, 2010 draft Annual Meeting Minutes (ATTACHMENT A) 3. Administrative Reports and Dean’s Report 4. Action Items – need motion to approve (ATTACHMENT B) Nominations for Standing Committees a. Courses and Curricula b. Elections and Credentials c. Library 5. Unit Reports 6. Academic Professional Award for Excellence and Faculty Awards for Excellence (ATTACHMENT C) 7. College Summary Data (Available on FAA Web site after meeting) a. Sabbatical Requests (ATTACHMENT D) b. Dean’s Special Grant Awards (ATTACHMENT E) c. Creative Research Awards (ATTACHMENT F) d. Student Scholarships/Enrollment (ATTACHMENT G) e. Kate Neal Kinley Memorial Fellowship (ATTACHMENT H) f. Retirements (ATTACHMENT I) g. Notable Achievements (ATTACHMENT J) h. College Committee Reports (ATTACHMENT K) 8. Other Business and Open Discussion 9. Adjournment Please join your colleagues for refreshments and conversation after the meeting in the Temple Buell Architecture Gallery, Architecture Building ATTACHMENT A ANNUAL MEETING MINUTES COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS 5:00P.M.; MONDAY, APRIL 5, 2010 FESTIVAL FOYER, KRANNERT CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 1. Welcome: Robert Graves, Dean Dean Robert Graves described the difficulties that the College faced in AY 2009-2010. Even during the past five years, when the economy was in better shape than it is now, it had become increasingly clear that the College did not have funds or personnel sufficient to accomplish comfortably all the activities it currently undertakes. In view of these challenges, the College leadership began a process of re- examination in an effort to find economies of scale, explore new collaborations, and spur creative thinking and cooperation. -

Finding Aid to Irene Rice Pereira Papers 1928-1971 Archives of Women Artists

Finding Aid to Irene Rice Pereira Papers 1928-1971 Archives of Women Artists Finding Aid Prepared by: Emily Moore (August, 2019) Collection Processed by: Patrick Brown, (August, 2006) Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center Email: [email protected] Phone: 202-266-2835 Table of Contents (Click a section title to skip down.) Overview ......................................................................................................i Administrative Information ............................................................................ ii Biographical Note ........................................................................................ iii Scope and Content Note ............................................................................... vi Organization and Arrangement Information .................................................... vi Names and Subject Terms ............................................................................ vii Container Inventory .................................................................................... vii Overview Repository Information: National Museum of Women in the Arts, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center 1250 New York Ave NW Washington, D.C. 20005 Email: [email protected] Phone: 202-783-5000 Title: Irene Rice Pereira Papers Provenance: The periodicals and books in the collection were part of the Library of Irene Rice Pereira, which was donated by the nephew of Pereira, Djelloul Marbrook, to the Washington Women’s Art Center in 1973. In 1986 the Irene Rice Periera Library was -

Modernist Delicacy David Smith at 100 Sara Krulwich/The New York Times Art Review | ‘David Smith’ by HOLLAND COTTER

Friday, February 03, 2006 Modernist Delicacy David Smith at 100 Sara Krulwich/The New York Times Art Review | ‘David Smith’ By HOLLAND COTTER SISSIES were second-class citizens in mid-20th-century American culture. And Smith’s mostly modest-size sculptures are set wide apart on the ramps, leaving art was a he-man’s game: booze, broads, Sasquatch manners, the whole nine expanses of white wall. This allows Wright’s spiral to assume its famously diffused yards. Sure, a little sensitivity was O.K., as long as you didn’t get carried away. It’s glow. And it lets Smith’s dark metal sculptures be exactly what Ms. Giménez says as if there was a sign at the Cedar Bar door: Girlie-men need not apply. Except they are: drawings in space. In short, what you get is a Guggenheim experience as this picture isn’t quite right. Look at the art. De Kooning painted the way Tamara well as a David Smith experience, which add up to a Modernism experience, with Toumanova danced, with a diva’s plush bravura. all the optical rigor and boutique-spirituality Pollock interwove strands of pigment as if he that that implies. were making lace. The sculptor David Smith, the biggest palooka of the Abstract Expressionist As in any career survey, an artist’s personality crowd, floated lines of welded steel in space the is also in play. Smith said that where you found way Eleanor Steber sang Mozart’s notes, with an his art, you would find him. And he makes an unbaroque fineness, an American-style delicacy. -

Colorful Language: Morris Louis, Formalist

© COPYRIGHT by Paul Vincent 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED To UNC-G professor Dr. Richard Gantt and my mother, for their inspiration and encouragement. COLORFUL LANGUAGE: MORRIS LOUIS, FORMALIST CRITICISM, AND MASCULINITY IN POSTWAR AMERICA BY Paul Vincent ABSTRACT American art at mid-century went through a pivotal shift when the dominant gestural style of Abstract Expressionism was criticized for its expressive painterly qualities in the 1950s. By 1960, critics such as Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried were already championing Color Field painting for its controlled use of color and flattened abstract forms. Morris Louis, whose art typifies this latter style, and the criticism written about his work provides a crucial insight into the socio-cultural implications behind this stylistic shift. An analysis of the formalist writing Greenberg used to promote Louis’s work provides a better understanding of not only postwar American art but also the concepts of masculinity and gender hierarchy that factored into how it was discussed at the time. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my thanks Dr. Helen Langa and Dr. Andrea Pearson for their wisdom, guidance, and patience through the writing of this thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Juliet Bellow, Dr. Joanne Allen, and Mrs. Kathe Albrecht for their unwavering academic support. I am equally grateful to my peers, Neda Amouzadeh, Lily Sehn, Kathryn Fay, Caitlin Glosser, Can Gulan, Rachael Gustafson, Jill Oakley, Carol Brown, and Fanna Gebreyesus, for their indispensable assistance and kind words. My sincere appreciation goes to The Phillips Collection for allowing me the peace of mind that came with working within its walls and to Mr. -

The Canonisation of Surrealism in the United States

The canonisation of Surrealism in the United States Sandra Zalman In a pointed assessment of the first show of Surrealism in New York, in 1932, the New York Times art critic asked, ‘How much of the material now on view shall we esteem “art,” and how much should be enjoyed as laboratory roughage’?1 The question encompassed the problem Surrealism posed for art history because it essentially went unanswered. Even after the 1936 endorsement by the Museum of Modern Art in a show organized by its founding director Alfred Barr (1902-1981), Surrealism continued to have a vexed relationship with the canon of modern art. Above all, the enterprise of canonisation is ironic for Surrealism – the Surrealists were self-consciously aiming to overthrow the category of art, but simultaneously participating in a tradition of avant-gardism defined by such revolution.2 Framing his exhibition, Barr presented Surrealism as both the most recent avant-garde export, and also as a purposeful departure from the avant-garde’s experimentation in form. Instead, Barr stressed that Surrealism focused on an anti-rationalist approach to representation. Though Barr made a strong case to integrate Surrealism into the broader understanding of modernism in the 1930s, and Surrealism was generally accepted by American audiences as the next European avant-garde, by the 1950s formalist critics in the U.S. positioned Surrealism as a disorderly aberration in modernism’s quest for abstraction. Surrealism’s political goals and commercial manifestations (which Barr’s exhibition had implicitly sanctioned by including cartoons and advertisements) became more and more untenable for the movement’s acceptance into a modern art canon that was increasingly being formulated around an idea of the autonomous self-reflexive work of art. -

This Page Intentionally Left Blank JAN MATULKA: the UNKNOWN MODERNIST EXHIBITION (Jan Matulka: the Modernist)

This page intentionally left blank JAN MATULKA: THE UNKNOWN MODERNIST EXHIBITION (Jan Matulka: The Modernist) By Rachael L. Holstege THESIS PROJECT Presented to the Arts Administration Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Administration August 6, 2020 2 Jan Matulka: The Unknown Modernist (Jan Matulka: The Modernist) Exhibition A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Masters of Arts Administration In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Administration From the Rackham School of Graduate Studies at the University of Michigan-Flint Rachael Holstege August 6, 2020 ____ _____________________________ Linda Johnson, PhD Thesis Committee Chair Lecturer II—DePartment of Art and Art History University of Michigan-Flint _________________________________ Nicole Broughton Thesis Committee Member Program Director-MA Arts Administration Lecturer IV—Theatre Management University of Michigan-Flint _________________________________ Benjamin Gaydos Thesis Committee Member Chair and Associate Professor of Design—DePartment of Art and Art History University of Michigan-Flint ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am incredibly grateful to the Flint Institute of Arts (FIA) for allowing me the time, space, and resources to execute this exhibition and accompanying online catalog. I’d like to especially thank FIA Curator of Collections and Exhibitions Tracee Glab for going above-and-beyond the duties of a boss to help me accomplish this entire endeavor. Thank you, Tom McCormick of the Estate of Jan Matulka, for your kindness, generosity, and most of all the loans for this exhibition. Thank you, Dr. Linda Johnson, for your continued advice and for stepping in when needed. -

Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287

Picasso and Braque A SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZED BY William Rubin \ MODERATED BY Kirk Varnedoe PROCEEDINGS EDITED BY Lynn Zelevansky THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK Contents Richard E. Oldenburg Foreword 7 William Rubin and Preface and Acknowledgments 9 Lynn Zelevansky Theodore Reff The Reaction Against Fauvism: The Case of Braque 17 Discussion 44 David Cottington Cubism, Aestheticism, Modernism 58 Discussion 73 Edward F. Fry Convergence of Traditions: The Cubism of Picasso and Braque 92 Discussion i07 Christine Poggi Braque’s Early Papiers Colles: The Certainties o/Faux Bois 129 Discussion 150 Yve-Alain Bois The Semiology of Cubism 169 Discussion 209 Mark Roskill Braque’s Papiers Colles and the Feminine Side to Cubism 222 Discussion 240 Rosalind Krauss The Motivation of the Sign 261 Discussion 287 Pierre Daix Appe ndix 1 306 The Chronology of Proto-Cubism: New Data on the Opening of the Picasso/Braque Dialogue Pepe Karmel Appe ndix 2 322 Notes on the Dating of Works Participants in the Symposium 351 The Motivation of the Sign ROSALIND RRAUSS Perhaps we should start at the center of the argument, with a reading of a papier colle by Picasso. This object, from the group dated late November-December 1912, comes from that phase of Picasso’s exploration in which the collage vocabulary has been reduced to a minimalist austerity. For in this run Picasso restricts his palette of pasted mate rial almost exclusively to newsprint. Indeed, in the papier colle in question, Violin (fig. 1), two newsprint fragments, one of them bearing h dispatch from the Balkans datelined TCHATALDJA, are imported into the graphic atmosphere of charcoal and drawing paper as the sole elements added to its surface. -

Primitivism" In2 0 T H Century

TH THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PRIMITIVISM" IN 20 CENTURY ART 11 WEST 53 STREET NEW YORK, NY 10019 Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (212) 708-940U FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August, 1984 No. 17 NEW EXHIBITION OPENING SEPTEMBER 27 AT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART EXAMINES "PRIMITIVISM" IN 20TH CENTURY ART Few if any external influences on the work of modern painters and sculptors have been more critical than that of the tribal arts of Africa, Oceania and North America. Since the turn of the century when Gauguin, Picasso, Matisse, and others first acquainted themselves with masks and sculptures from these areas, modern artists have continued to display strong interest in the art and culture of tribal societies. The term "primitivism" is used to describe the Western response to tribal cultures as revealed in the work and thought of modern artists. Recognizing the importance of this issue in modern art history--and the relative lack of serious research devoted to it--The Museum of Modern Art in New York this fall presents a groundbreaking exhibition that underscores the parallelisms that exist between the two arts. Entitled "PRIMITIVISM" IN 20TH CENTURY ART: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, the exhibition, which opens on September 27 and runs through January 15, 1985, is the first ever to juxtapose modern and tribal objects in the light of informed art history. William Rubin, head of the Museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture and director of the landmark 1980 Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective, has organized the show in collaboration with Professor Kirk Varnedoe of New York University's more/ The exhibition and its national tour are sponsored by Philip Morris Incorporated.