Noh :A Mirror of the Spirit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being in the Noh: an Introduction to Japanese Noh Plays —

Being in the Noh: An Introduction to Japanese Noh Plays — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=628 Conventions of the Noh Play A. The Five Types of Noh Plays: 1. The god play (Kami)—congratulatory piece praising the gods in a quiet, dignified tone. 2. The warrior play (Shura)—a slain warrior comes back as a ghost and relives his suffering 3. The woman play (Katsura)—an elegant, stylish woman is the protagonist 4. The mad woman (or madness) play/realistic play 5. The supernatural (or demon) play (Kiri)—a battle between a demon or other supernatural figure and a hero in which the demon is usually subdued. B. The Order of Performance 1. Okina-Sanbaso—a ritual piece 2. The god play (Noh) 3. A Kyogen play 4. The warrior play (Noh) 5. A Kyogen play 6. The woman play (Noh) 7. A Kyogen play 8. The mad play (Noh) 9. A Kyogen play 10. The demon play C. The Characters of a Noh Play 1. Shite (pronounced sh'tay)—the main character, the “doer” of the play Maejite—(pronounced may-j’tay) the shite appears in the first part of the play as an ordinary person Nochijite—(pronounced no-chee-j’tay) the shite disappears and then returns in the second part of the play in his true form as the ghost of famous person of long ago. 2. Tsure—(pronounced tsoo-ray) the companion of the shite 3. Waki—a secondary or “sideline” character, often a traveling priest, whose questioning of the main character is important in developing the story line 4. -

War Sum up Music

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #WarSumUp Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer War Sum Up Music. Manga. Machine. Hotel Pro Forma Vocals by Latvian Radio Choir BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Nov 1 & 2 at 7:30pm Approximate running time: one hour & 20 minutes; no intermission Directed by Kirsten Dehlholm BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Music by The Irrepressibles, Santa Ratniece with Gilbert Nouno Concept by Willie Flindt and Kirsten Dehlholm Musical direction by Kaspars Putnins Costumes by Henrik Vibskov Leadership support for War Sum Up provided by The Barbaro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation Lighting design by Jesper Kongshaug Libretto from classic Noh theater edited by Willie Flindt Leadership support for opera at BAM Manga drawings by Hikaru Hayashi provided by: The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Performed in Japanese with English titles The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation Stavros Niarchos Foundation Premiere: September 2, 2011, Latvian National Additional support for opera at BAM provided Opera, Riga by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Photo: Gunars Janaitis War Sum Up Latvian Radio Choir Soprano Ieva Ezeriete, Inga Martinsone, Iveta Romanca¯ne Alto Li¯ga Paegle, Dace Strautmane, Inga Žilinska Tenor Aigars Reinis, Ka¯rlis Ru¯tenta¯ls, Egils Ja¯kobsons Bass Gundars Dzil¸ums, Ja¯nis Kokins, Ja¯nis Strazdin¸š “Gamemaster” Ieva Ezeriete “Soldier” Aigars Reinis “Warrior” Gundars Dzilums “Spy” Liga Paegle Set design Kirsten Dehlholm, Willie Flindt, Jesper Kongshaug Video technique Kasper Stouenborg Video design Sine Kristiansen Manga drawings Hikaru Hayashi Black and white photos Zoriah Miller, Dallas Sells, Timothy Fadek, Kirtan Patel, Mário Porral, Richard Bunce Director’s assistant Jon R. -

Noh Theater and Religion in Medieval Japan

Copyright 2016 Dunja Jelesijevic RITUALS OF THE ENCHANTED WORLD: NOH THEATER AND RELIGION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN BY DUNJA JELESIJEVIC DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in East Asian Languages and Cultures in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Elizabeth Oyler, Chair Associate Professor Brian Ruppert, Director of Research Associate Professor Alexander Mayer Professor Emeritus Ronald Toby Abstract This study explores of the religious underpinnings of medieval Noh theater and its operating as a form of ritual. As a multifaceted performance art and genre of literature, Noh is understood as having rich and diverse religious influences, but is often studied as a predominantly artistic and literary form that moved away from its religious/ritual origin. This study aims to recapture some of the Noh’s religious aura and reclaim its religious efficacy, by exploring the ways in which the art and performance of Noh contributed to broader religious contexts of medieval Japan. Chapter One, the Introduction, provides the background necessary to establish the context for analyzing a selection of Noh plays which serve as case studies of Noh’s religious and ritual functioning. Historical and cultural context of Noh for this study is set up as a medieval Japanese world view, which is an enchanted world with blurred boundaries between the visible and invisible world, human and non-human, sentient and non-sentient, enlightened and conditioned. The introduction traces the religious and ritual origins of Noh theater, and establishes the characteristics of the genre that make it possible for Noh to be offered up as an alternative to the mainstream ritual, and proposes an analysis of this ritual through dynamic and evolving schemes of ritualization and mythmaking, rather than ritual as a superimposed structure. -

Experience Ikebana, Sashimono, Kimono, Shishimai, and Noh and More Exciting Traditional Japanese Culture!

September 5, 2018 Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture) Arts Council Tokyo Traditional Culture Program Arts Council Tokyo offers many activities to learn more about Japan Experience Ikebana, Sashimono, Kimono, Shishimai, and Noh and more exciting traditional Japanese culture! Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture) implements various programs aimed for people who are not familiar with traditional Japanese culture and arts, like foreign people and children, to freely enjoy authentic traditional culture and performing arts, with the theme of “Approaching Tokyo Tradition.” The Council will hold a Japanese flower arrangement (Ikebana), Edo Sashimono, and Kimono dressing experience for foreign visitors on Oct. 20 and 21, in conjunction with the Tokyo Grand Tea Ceremony taking place at the Hama-rikyu Gardens. The second edition of the Shishimai and Acrobatics Experiences will also be held in October at Haneda Airport International Passenger Terminal. In addition, “Noh ‘SUMIDAGAWA’ -Sound of prayer cradled in sorrow-“will be held in February 2019. Stay tuned for the many exciting programs planned in the coming months. Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Supported by and in Tokyo Metropolitan Organized by Foundation for History and Culture) cooperation with Government The latest information for programs in the future will be updated on the following official website (in Japanese and English) web www.tokyo-tradition.jp facebook TokyoTradition twitter TYO_tradition Contact -

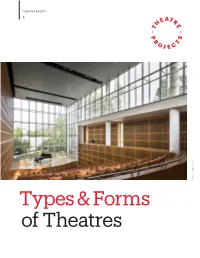

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

Parsi Theater, Urdu Drama, and the Communalization of Knowledge: a Bibliographic Essay

Parsi Theater, Urdu Drama, and the Communalization of Knowledge: A Bibliographic Essay I its remarkable century-long history traversing the colonial and nation- alist eras, the Parsi theater was unique as a site of communal harmony. The Parsi theater began in Bombay in the early s and fanned out across South and Southeast Asia by the s. During the twentieth cen- tury, major Parsi theatrical companies flourished in Lahore, Delhi, and Calcutta, exerting a huge impact on the development of modern drama, regional music, and the cinema. Parsis, Hindus, Muslims, Anglo-Indians, and Baghdadi Jews consorted amicably in both residential and traveling companies. Although company ownership usually remained in Parsi hands, actors were drawn from many communities, as were professional writers, musicians, painters, stage hands, and other personnel. As Såmn≥t^ Gupta makes clear, it was Parsis, non-Parsis, Hindus, Muslims, and Christians who spread the art of theatre by founding theatrical companies, who built playhouses and encouraged drama, who became actors and popularized the art of acting, who composed innumerable dramas in Gujarati, Hindi, and Urdu, who composed songs and defended classical music, and who wrote descriptions of the Parsi stage and related matters.1 Audiences similarly were heterogeneous, comprised of diverse relig- ious, ethnic, and linguistic groups and representing a wide range of class 1Såmn≥t^ Gupta, P≥rsµ T^iy®ªar: Udb^av aur Vik≥s (Allahabad: Låkb^≥ratµ Prak≥shan, ), dedication (samarpan), p. • T A U S positions. Sections of the public were catered to by particular narrative genres, including the Indo-Muslim fairy romance, the Hindu mythologi- cal, and the bourgeois social drama, yet no genre was produced exclu- sively for a particular viewership. -

Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), Pp

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Performing Prayer, Saving Genji, and Idolizing Murasaki Shikibu: Genji Kuyō in Nō and Jōruri Author(s): Satoko Naito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 3-28 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/naito-satoko- gkuyojoruri_jsr.pdf ______________________________________________________________ PERFORMING PRAYER, SAVING GENJI, AND IDOLIZING MURASAKI SHIKIBU: GENJI KUYŌ IN NŌ AND JŌRURI1 Satoko Naito University of Maryland, College Park Introduction The Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron [lit. “Story of Murasaki Shikibu’s Fall] tells that after her death Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) was cast to hell.2 The earliest reference is found in Genji ipponkyō [Sutra for Genji] (ca. 1166), which recounts a Buddhist kuyō (dedicatory rite) performed on her behalf, with the reasoning that the Heian author had been condemned to eternal suffering in hell for writing Genji monogatari [The Tale of Genji] (ca. 1008). Though Genji ipponkyō makes no explicit claim to the efficacy of the kuyō, its performance is presumably successful and saves the Genji author. In such a case the earliest extant utterance of the Murasaki-in-hell story is coupled with her subsequent salvation, and the Genji author, though damned, is also to be saved.3 It may be more accurate, then, to say that the Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron is about Murasaki Shikibu’s deliverance, rather than her fall (daraku). Through the medieval period and beyond, various sources recounted the execution of kuyō rites conducted for The Tale of Genji’s author, often initiated and sponsored by women.4 Such stories of Genji kuyō 1 Author’s Note: I thank those who commented on earlier versions of this paper, in particular D. -

The Disaster of the Third Princess

6. Two Post-Genji Tales on The Tale of Genji Two roughly late twelfth century works represent a transition in the reception of The Tale of Genji. The first, Genji shaku by Sesonji Koreyuki (d. 1175), begins the long line of scholarly commentaries that are still being written today.1 The second, Mumyōzōshi (ca. 1200, attributed to Shunzei’s Daughter), can perhaps be said to round off the preceding era, when Genji was simply a monogatari (tale) among others, enjoyed above all by women. In contrast with Koreyuki’s textual glosses, Mumyōzōshi gives passionate reader responses to characters and incidents in several monogatari, including Genji. The discovery of something like it from much earlier in the preceding two hundred years would be very welcome. Fortunately, some evidence of earlier reader reception survives after all, not in critical works, but in post-Genji tales themselves. Showing as they do demonstrable Genji influence, they presumably suggest at times, in one way or another, what the author made of Genji, or how she understood this or that part of it. This essay will discuss examples from Sagoromo monogatari (ca. 1070–80, by Rokujō no Saiin Senji, who served the Kamo Priestess Princess Baishi)2 and Hamamatsu Chūnagon monogatari (ca. 1060, attributed to the author of Sarashina nikki). Chief among them are the meaning of the chapter title “Yume no ukihashi”; the question of what happens to Ukifune between “Ukifune” and “Tenarai”; and the significance of Genji’s affair with Fujitsubo. Discussion of these topics, especially the second, will hark back at times to material presented in earlier essays, although this time with a different purpose. -

THE WISDOM of NOH THEATER Masayoshi Morioka the Practice Of

International Journal for Dialogical Science Copyright 2015 by Masayoshi Morioka Fall 2015 Vol. 9, No. 1, 81-95 HOW TO CREATE MA–THE LIVING PAUSE–IN THE LANDSCAPE OF THE MIND: THE WISDOM OF NOH THEATER Masayoshi Morioka Kobe University, Japan Abstract. In this research, the author explores the characteristics of zone of contact in therapeutic conversation. The transitional psychic space between Me and Mine is the basis on which the landscape of the mind develops the I-positioning of the dialogical self. In further discussion, the author quotes notes from the dramaturgical theory of Zeami, who established traditional Japanese Noh theatre. Concepts related to ma are examined. The results are as follows. The therapist creates ma (a “living pause”), which connects one mind to another; this reflects the moment of senu-hima (“no-action”) in Noh theatre. Change in psychotherapy includes a process of distancing oneself from oneself; this resembles the concept of riken (“detached seeing”). The concept of sho-shin (first intent) in Noh theatre may be experienced in the moment at which spontaneous responsiveness emerges in the dialogical relationship. Keywords: distancing the self, zone of contact, dialogical uncertainty, Noh theatre, ma The practice of the dialogical self involves talking about oneself to others, and talking to oneself silently. This double conversation (i.e. self-to-self and self-to-other) creates a dialogical space that articulates and differentiates one’s self-narrative on the basis of inner and outer dialogues. It is difficult to hear one’s own voice in the dialogical double space of internal and external dialogue; however, it is necessary to create this double space in conversation with others. -

Draper DEPARTMENT: Costumes REPORTS TO: Costume Director PREPARED DATE: June 11, 2021 CLASSIFICATION: FLSA: Hourly, Non-Exempt

JOB TITLE: Draper DEPARTMENT: Costumes REPORTS TO: Costume Director PREPARED DATE: June 11, 2021 CLASSIFICATION: FLSA: Hourly, Non-Exempt MISSION STATEMENT The mission of Dallas Theater Center is to engage, entertain and inspire our diverse community by creating experiences that stimulate new ways of thinking and living. We will do this by consistently producing plays, educational programs, and other initiatives that are of the highest quality and reach the broadest possible constituency. EQUITY, DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION STATEMENT ALL ARE WELCOME! At Dallas Theater Center, we want to be the best place to work and see theater, and to be a positive and transformational force in Dallas and beyond. We stand up for equity, diversity and inclusion across our company and community. As a leading national theater, we recognize that building an equitable, diverse, and inclusive environment is central to our relevance and sustainability in the community we serve and love. *For complete statement, please see final page of this posting POSITION SUMMARY An active member of Dallas Theater Center (DTC)’s Production Department, the Draper is responsible for pattern making, construction, and the fit of all costumes. The Draper reports directly to the Costume Director, and is responsible for effectively supporting Costume Designers, ensuring that high artistic standards are met at all times. This is a full-time, non-exempt position, which is eligible for overtime. This position includes a full benefits package: medical, dental and vision insurance, DTC-paid life insurance, voluntary life insurance and 403b programs, complimentary tickets and generous paid-time off. Some nights and weekends will be required as needed throughout the season. -

Nohand Kyogen

For more detailed information on Japanese government policy and other such matters, see the following home pages. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website http://www.mofa.go.jp/ Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater oh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four N forms of classical theater, the other two being kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its broadest sense includes the comic theater kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical form in the 14th century, making it the oldest extant professional theater in the world. Although noh and kyogen developed together and are inseparable, they are in many ways exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a symbolic theater with primary importance attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other hand, primary importance is attached to making people laugh. History of the Noh Theater Noh performance chance to further refine the noh aesthetic Scene from a Kanze In the early 14th century, acting troupes principles of monomane (the imitation of school performance of the in a variety of centuries-old theatrical play Aoi no ue (Lady Aoi). things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic © National Noh Theater traditions were touring and performing ideal emphasizing the suggestion of mystery at temples, shrines, and festivals, often and depth. In addition to writing some of with the patronage of the nobility. The the best-known plays in the noh repertoire, performing genre called sarugaku was one Zeami wrote a series of essays which of these traditions. The brilliant playwrights defined the standards for noh performance and actors Kan’ami (1333– 1384) and his son in the centuries that followed.