UC Riverside UCR Honors Capstones 2018-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Care and Feeding of the WHOLE MUSICAL YOU! Created by the Students and Instructors of the New Trier Jazz Ensembles Program

The Care and Feeding of the WHOLE MUSICAL YOU! Created by the students and instructors of the New Trier Jazz Ensembles Program The many domains of the whole musical you… TECHNICIAN LITERATE JAZZ MUSICIAN COMPOSER/ARRANGER IMPROVISER LISTENER CRITIC HISTORIAN PERFORMER Tools/resources needed to develop the whole musical you… desire goals time space guidance enjoyment DEVELOPING AS A TECHNICIAN Practice with a metronome Track your progress – make your assessment quantitative (numbers) Take small, measured steps Record yourself, and be critical (also be positive) Use SmartMusic as a scale-practicing companion Go bonkers with scales Be creative with scales (play scales in intervals, play scales through the entire range of your instrument, play scales starting on notes other than the tonic, remember that every scale also represents a chord for each note in that scale, find new patterns in your scales Challenge yourself – push your boundaries Use etudes and solo transcriptions to push yourself Use a metronome!!! DEVELOPING AS A LITERATE JAZZ MUSICIAN Practice sight-reading during every session Learn tunes (from the definitive recorded version when possible) Learn vocabulary Learn chords on the piano DEVELOPING AS A COMPOSER/ARRANGER Compose a melody Compose a chord progression Compose a melody on an established chord progression (called a contrafact) Re-harmonize an established melody Write an arrangement of an established melody DEVELOPING AS AN IMPROVISER Transcribe a solo Compose a solo for a tune you’re -

Harmony Crib Sheets

Jazz Harmony Primer General stuff There are two main types of harmony found in modern Western music: 1) Modal 2) Functional Modal harmony generally involves a static drone, riff or chord over which you have melodies with notes chosen from various scales. It’s common in rock, modern jazz and electronic dance music. It predates functional harmony, too. In some types of modal music – for example in jazz - you get different modes/chord scale sounds over the course of a piece. Chords and melodies can be drawn from these scales. This kind of harmony is suited to the guitar due to its open strings and retuning possibilities. We see the guitar take over as a songwriting instrument at about the same time as the modes become popular in pop music. Loop based music also encourages this kind of harmony. It has become very common in all areas of music since the late 20th century under the influence of rock and folk music, composers like Steve Reich, modal jazz pioneered by Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and influences from India, the Middle East and pre-classical Western music. Functional harmony is a development of the kind of harmony used by Bach and Mozart. Jazz up to around 1960 was primarily based on this kind of harmony, and jazz improvisation was concerned with the improvising over songs written by the classically trained songwriters and film composers of the era. These composers all played the piano, so in a sense functional harmony is piano harmony. It’s not really guitar shaped. When I talk about functional harmony I’ll mostly be talking about ways we can improvise and compose on pre-existing jazz standards rather than making up new progressions. -

Chapter 12 Answer Key.Indd

Chapter 12 Answer Key Applications Exercises 1. Spell and resolve dominant seventh chords in root position. Chord voic- ings should be either complete (C) or incomplete (IN), as indicated below the Roman numerals. © 2019 Taylor & Francis 2 Chapter 12 Answer Key 2. Spell and resolve inverted dominant seventh chords. All chords should be complete. Add any necessary inversion symbol to the tonic chord. 3. Spell and resolve leading-tone seventh chords in root position and inversion. Add any necessary inversion symbol to the tonic chord. © 2019 Taylor & Francis Chapter 12 Answer Key 3 4. Complete the following chord progression in four voices. Provide a syntactic analysis below the Roman numerals. The syntactic analysis is shown below the Roman numerals. The voicing of chords and voice leading between chords is variable. Brain Teaser What triad is shared by V7 and viiØ7? How do these two seventh chords differ in terms of their scale-degree contents? Answer: V7 and viiØ7 share the leading-tone triad (viiO). The two chords differ by 5ˆ (the root of V7) and 6ˆ (the seventh of viiØ7). 5ˆ and 6ˆ are a whole step apart (a half step in minor, where 6ˆ is the seventh of viiO7). Thinking Critically An incomplete triad or seventh chord is missing its fifth. Compared with other chord members (root, third, and seventh), why is it possible to omit the fifth (i.e., why is this particular chord member nonessential)? Discussion The root of a chord is necessary to identify the chord and its function, the third determines the quality of the chord (major or minor), and the seventh must be present for a chord to be an actual seventh chord (rather than a triad). -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Katherine Riddle

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS Katherine Riddle Soprano “My Life’s Delight” Andrew Welch, piano Carley DeFranco, soprano Ryan Burke, tenor Sunday, March 3, 2013 at 5:00 p.m. Abramson Family Recital Hall Katzen Arts Center American University This senior recital program is in partial fulfillment of the degree program Bachelor of Arts in Music, Vocal Performance and the American University Honors Capstone Program. Ms. Riddle is a student of Dr. Linda Allison. THANK YOU… ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER ( b. 1948 ) wrote the music for the longest running show on Broadway, The Phantom of …to all of the faculty and staff in the music and theatre departments the Opera. This musical is based on a French novel Le Fantôme de that have supported, mentored and encouraged me. Thank l'Opéra by Gaston Leroux. The plot centers around the beautiful soprano, you for pushing me to strive for greatness and helping me to grow as a Christine, who becomes the object of the Phantom’s affections. As the prima person and as a performer. donna, Carlotta, is rehearsing for a performance, a backdrop collapses on her without warning. Carlotta storms offstage, refusing to perform and Christine is tentatively chosen to take her place in the opera that night. She is …to my wonderful friends who are always there for me to cheer, to cry, ready for the challenge. to cuddle or to celebrate. You guys are irreplaceable! Think of Me …to my amazing family (especially my incredible parents) for always Think of me, think of me fondly when we’ve said goodbye being my cheerleaders, giving me their undying love and support and, Remember me, every so often, promise me you’ll try most of all, for helping me pursue my dream. -

Part One G Cadd9 Chord Fingerings

The Four Chord Secret to Playing Lots of Songs www.guitarlessonsforbeginnersonline.net Chord Fingerings: Part One G Cadd9 Chord Fingerings: Part Two D Em (E minor) © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Playing Chord Progressions A chord progression is a series of chords played one after the other. Most songs consist of several different chord progressions. Learning to play the chord progressions in this lesson will help you learn to play many different songs. Mastering the chord fingerings and chord progressions in this lesson will help you quickly learn to play many different songs in different styles of music. These fundamental chords are crucial to your development and improvement as a guitar player—learn them well and learn to change between them. You will use them for the rest of your guitar playing career! Chord Progression One Chords Used: D Cadd9 G Play four strums on each chord and change to the next: |D / / / |Cadd9 / / / |G / / / | (repeat) This chord progression is similar to the one used in the song “Can’t You See?” by the Marshall Tucker Band. Chord Progression Two Chords Used: D Cadd9 G This progression uses the same chords as the first one. The difference is that we will pick some of the notes in the first two chords and end with a strum on the final G chord. Key point to remember: Even though the pick hand is playing some single notes, your fret hand only needs to play the chord shapes, just like in Progression One. D Cadd9 G This chord progression and picking pattern is similar to the one used in the song “Sweet Home Alabama” by Lynyrd Skynyrd. -

French Stewardship of Jazz: the Case of France Musique and France Culture

ABSTRACT Title: FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, Master of Arts, 2008 Directed By: Richard G. King, Associate Professor, Musicology, School of Music The French treat jazz as “high art,” as their state radio stations France Musique and France Culture demonstrate. Jazz came to France in World War I with the US army, and became fashionable in the 1920s—treated as exotic African- American folklore. However, when France developed its own jazz players, notably Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, jazz became accepted as a universal art. Two well-born Frenchmen, Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay, embraced jazz and propagated it through the Hot Club de France. After World War II, several highly educated commentators insured that jazz was taken seriously. French radio jazz gradually acquired the support of the French government. This thesis describes the major jazz programs of France Musique and France Culture, particularly the daily programs of Alain Gerber and Arnaud Merlin, and demonstrates how these programs display connoisseurship, erudition, thoroughness, critical insight, and dedication. France takes its “stewardship” of jazz seriously. FRENCH STEWARDSHIP OF JAZZ: THE CASE OF FRANCE MUSIQUE AND FRANCE CULTURE By Roscoe Seldon Suddarth Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2008 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard King, Musicology Division, Chair Professor Robert Gibson, Director of the School of Music Professor Christopher Vadala, Director, Jazz Studies Program © Copyright by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth 2008 Foreword This thesis is the result of many years of listening to the jazz broadcasts of France Musique, the French national classical music station, and, to a lesser extent, France Culture, the national station for literary, historical, and artistic programs. -

Trent 91; First Steps Towards a Stylistic Classification (Revised 2019 Version of My 2003 Paper, Originally Circulated to Just a Dozen Specialists)

Trent 91; first steps towards a stylistic classification (revised 2019 version of my 2003 paper, originally circulated to just a dozen specialists). Probably unreadable in a single sitting but useful as a reference guide, the original has been modified in some wording, by mention of three new-ish concordances and by correction of quite a few errors. There is also now a Trent 91 edition index on pp. 69-72. [Type the company name] Musical examples have been imported from the older version. These have been left as they are apart from the Appendix I and II examples, which have been corrected. [Type the document Additional information (and also errata) found since publication date: 1. The Pange lingua setting no. 1330 (cited on p. 29) has a concordance in Wr2016 f. 108r, whereti it is tle]textless. (This manuscript is sometimes referred to by its new shelf number Warsaw 5892). The concordance - I believe – was first noted by Tom Ward (see The Polyphonic Office Hymn[T 1y4p0e0 t-h15e2 d0o, cpu. m21e6n,t se suttbtinigt lneo] . 466). 2. Page 43 footnote 77: the fragmentary concordance for the Urbs beata setting no. 1343 in the Weitra fragment has now been described and illustrated fully in Zapke, S. & Wright, P. ‘The Weitra Fragment: A Central Source of Late Medieval Polyphony’ in Music & Letters 96 no. 3 (2015), pp. 232-343. 3. The Introit group subgroup ‘I’ discussed on p. 34 and the Sequences discussed on pp. 7-12 were originally published in the Ex Codicis pilot booklet of 2003, and this has now been replaced with nos 148-159 of the Trent 91 edition. -

Of Audiotape

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. DAVID N. BAKER NEA Jazz Master (2000) Interviewee: David Baker (December 21, 1931 – March 26, 2016) Interviewer: Lida Baker with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 19, 20, and 21, 2000 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 163 pp. Lida: This is Monday morning, June 19th, 2000. This is tape number one of the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project interview with David Baker. The interview is being conducted in Bloomington, Indiana, [in] Mr. Baker’s home. Let’s start with when and where you were born. David: [I was] born in Indianapolis, December 21st, 1931, on the east side, where I spent almost all my – when I lived in Indianapolis, most of my childhood life on the east side. I was born in 24th and Arsenal, which is near Douglas Park and near where many of the jazz musicians lived. The Montgomerys lived on that side of town. Freddie Hubbard, much later, on that side of town. And Russell Webster, who would be a local celebrity and wonderful player. [He] used to be a babysitter for us, even though he was not that much older. Gene Fowlkes also lived in that same block on 24th and Arsenal. Then we moved to various other places on the east side of Indianapolis, almost always never more than a block or two blocks away from where we had just moved, simply because families pretty much stayed on the same side of town; and if they moved, it was maybe to a larger place, or because the rent was more exorbitant, or something. -

Seventh Chord Progressions in Major Keys

Seventh Chord Progressions In Major Keys In this lesson I am going to focus on all of the 7th chord types that are found in Major Keys. I am assuming that you have already gone through the previous lessons on creating chord progressions with basic triads in Major and Minor keys so I won't be going into all of the theory behind it like I did in those lessons. If you haven't read through those lessons AND you don't already have that knowledge under your belt, I suggest you download the FREE lesson PDF on Creating and Writing Major Key Chord Progressions at www.GuitarLessons365.com. So What Makes A Seventh Chord Different From A Triad? A Seventh Chord IS basically a triad with one more note added. If you remember how we can get the notes of a Major Triad by just figuring out the 1st, 3rd and 5th tones of a major scale then understanding that a Major Seventh Chord is a four note chord shouldn't be to hard to grasp. All we need to do is continue the process of skipping thirds to get our chord tones. So a Seventh Chord would be spelled 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th. The added 7th scale degree is what gives it it's name. That is all it is. :) So what I have done for this theory lesson is just continue what we did with the basic triads, but this time made everything a Seventh Chord. This should just be a simple process of just memorizing each chord type to it's respective scale degree. -

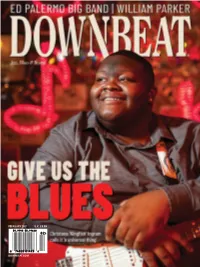

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

MUS 390 Assignment #10 (Regular Credit) – Jazz Standard Rewrite The

MUS 390 Assignment #10 (regular credit) – Jazz Standard Rewrite The purpose of this assignment is to put you in touch with the harmonic, melodic and formal conventions of a traditional 32-bar jazz standard. On a separate piece (or pieces) of staff paper, write (by hand) your own melody of a 32-bar jazz standard using the existing chords (known as a contrafact). You can choose any 32-bar piece, but not “Satin Doll” or “All The Things You Are”. If you need help choosing one or tracking one down, I will help you. 1. Copy over the chart, maintaining the same chords, measure for measure (do not use any chord substitutions) 2. Make up your own melody, but follow the melodic formatting of the original: • Pay attention to the number of motifs used in the original and apply the same format to your melody o if the original melody uses one motif throughout, do the same o if the original melody uses different motifs in one or multiple sections, do the same • Also apply the same phrasing as the original: o if the original melody uses 4-meause phrases, then you do the same; o if the original melody uses 8-measure phrases, do the same) 3. While you have a lot of latitude as to how you compose your melody, it should more-so (not less-so) use chord tones against the accompanying harmony 4. On your chart, follow all notation conventions • Make sure there is enough room between to accommodate the notes and chord symbols • if there is not enough room, skip a staff system and use two pages (stapled) if necessary • Make the notation look neat and readable 5.