Kalyan-Dombivli & Mira-Bhayandar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of PAN Maharasthra Empanelled

MDINDIA HEALTH INSURANCE TPA PVT. LTD. Provider Management IN PAN Maharashtra Empanelled Hospital List Date : 05_10_2018 This has reference to captioned subject and inform you that the Cashless Facilities will only be available in PPN Hospitals (For Mumbai and Pune City), the list of the hospital is attached herewith. You are requested to kindly note of the same inform all Dy. CIROs so that they can avail this facility only in PPN Hospitals in case of Pune, Mumbai and other PPN Cities across India. Sr. No. Hospital Name Location City State Address Status PPN Hospital PPNCITY 1 Aashirwad Critical Care Unit And Multispeciality Hospital Mulund Mumbai Maharashtra Navinjyot , RRT Road, Mulund West Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 2 Aastha Health Care Mulund Mumbai Maharashtra Mulund Colony, Off LBS Rd, Opp Chheda Petrol Pump Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 3 Aastha Hospital Kandivali Mumbai Maharashtra 65, Balasinor Society, S.V.Road, Opp Fire Brigade, Kandivali W Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 4 Aayush Eye Clinic Chembur Mumbai Maharashtra 201/202, Coral Classic, 20th Road, Near Ambedkar Garden, ChemburEmpanelled IN PPN Mumbai 5 Abhishek Nursing Home Ghatkopar Mumbai Maharashtra Jagriti CHS, Nr Maratha Mandir Co-op Bank, Bhatwadi Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 6 Aditi Hospital Mulund Mumbai Maharashtra 185 - R, Alhad, P.K Road, Above Corporation Bank Mulund (W) Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 7 Aditi Hospital Malad Mumbai Maharashtra 1st Floor, Param Ratan, Opp. Post Office, Jakeria Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 8 Advanced Eye Hospital & Institute Sanpada Mumbai Maharashtra 30 the abbaires Sector 17 palm beach road sanpada Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 9 Aggarwal Eye Hospital Andheri Mumbai Maharashtra 102/5, Ketayun Mansion, Shahaji Raje Marg, Above T Empanelled IN PPN Mumbai 10 Agrawal Eye Hospital Malad Mumbai Maharashtra 1st floor, maharaja apt, Malad (W), S V Road, opp. -

Thane to Dombivli Local Train Time Table

Thane To Dombivli Local Train Time Table Suspect and achondroplastic Baird anagrammatise her pod oblique or jewels geognostically. Dion underbuys her investments furtively, octupled and invited. Fabian never bedims any toploftiness satirising continually, is Gerrit wounded and casemated enough? These Wallcoverings in a slight tickle the optic nerve with how bold lines and yes their smart trickery, cerating new perspectives. Plz send me the cab services, helping you buy either a dombivli train and. It opens up the dombivli time table list of transport in school when we prepare our detailed map too provide vital information local time table between bandra stn. Please get complete information local train to time thane to submit your friends a face mask on suburban railway route finder provides users maps. They serve south indian railways also has helped me train table train to thane dombivli local time. Villas for trains between andheri to passengers having to start running in local time table particular city of foods like. Important Note: This website NEVER solicits for Money or Donations. The above table point of new posts by the date of flexibility they will take more. This website gives the travel information and distance for all the cities in the globe. Be lost between CSMT and KurlaThaneDombivali during the early period. Use the dombivli table of the benefit of their focus is not enough space in each map. Xpress has always room within a railway local train time from a little concerned but you in all train to thane dombivli local train time table sorry for. Khalapur, Raigad district which is well connected to Panvel, Mumbai Thane. -

Estate 5 BHK Brochure

4 & 5 BHK LUXURY HOMES Hiranandani Estate, Thane Hiranandani Estate, Off Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) Call:(+91 22) 2586 6000 / 2545 8001 / 2545 8760 / 2545 8761 Corp. Off.: Olympia, Central Avenue, Hiranandani Business Park, Powai, Mumbai - 400 076. [email protected] • www.hiranandani.com Rodas Enclave-Leona, Royce-4 BHK & Basilius-5 BHK are mortgaged with HDFC Ltd. The No Objection Certificate (NOC)/permission of the mortgagee Bank would be provided for sale of flats/units/property, if required. Welcome to the Premium Hiranandani Living! ABUNDANTLY YOURS Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. EXTRAVAGANTLY, oering style with a rich sense of prestige, quality and opulence, heightened by the cascades of natural light and spacious living. Actual image shot at Rodas Enclave, Thane. LUXURIOUSLY, navigating the chasm between classic and contemporary design to complete the elaborated living. • Marble flooring in living, dining and bedrooms • Double glazed windows • French windows in living room • Large deck in living/dining with sliding balcony doors Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. CLASSICALLY, veering towards the modern and eclectic. Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. The furniture & fixtures shown in the above flat are not part of apartment amenities. EXCLUSIVELY, meant for the discerning few! Here’s an access to gold class living that has been tastefully designed and thoughtfully serviced, oering only and only a ‘royal treatment’. • Air-conditioner in living, dining and bedrooms • Belgian wood laminate flooring in common bedroom • Space for walk–in wardrobe in apartments • Back up for selected light points in each flat Standard apartment of Basilius building for reference purpose only. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

BANK NAME IFSC Code Address ABHYUDAYA CO-OP BANK LTD ABHY0065001 251, Abhyudaya Bank Bldg, Perin Nariman Street, Fort, Mumbai 400 001, ABN AMRO BANK N.V

BANK NAME IFSC Code Address ABHYUDAYA CO-OP BANK LTD ABHY0065001 251, ABHYudaya Bank Bldg, Perin Nariman Street, Fort, Mumbai 400 001, ABN AMRO BANK N.V. ABNA0000001 414, Empire Complex, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel (West), Mumbai 400 013 ABU DHABI COMMERCIAL BANK ADCB0000001 75-B,Rehmat Manzil,Vir Nariman Road,Chrchgate,Mumbai-4000020 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0888888 Allahabad Bank, 3rd Floor, Allahabad Bank Building, 37, Mumbai Samachar Marg, Fort ,Mumbai -23 AMERICAN EXPRESS BANK AMEX0000001 Oriental Building, Ground floor, 364 Dr. D. N. Road, Fort, Mumbai 400 001. ANDHRA BANK ANDB0TRESUY 1st Floor Bansi Lal Building, 11 Homi Modi Street, Fort, MUMBAI - 400 023 BANK OF AMERICA BOFA0MM6205 Express Towers, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BANK OF BAHRAIN AND KUWAIT BBKM0000001 225 Jolly Maker Chamber II,Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BANK OF BARODA BARB0TREASU 6th Floor, Kalpataru Heritage Building,Nanik Motwani Marg, Fort, Mumbai - 400 023. BANK OF INDIA BKID000PIGW Star House, 8th floor, C-5, "G" Block, Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051 BANK OF MAHARASHTRA MAHB0003007 Treasury and International Banking Division, 2nd Floor, Maker Chamber III, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 02 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA NOSC0000MUM Mittal Tower ‘B’ Wing, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BANK OF RAJASTHAN BRAJ0003350 Treasury Branch, 18/20 Cawasji Patel Street, Jeevan Jyoti Bldg., Fort, Mumbai - 400 023.(Maharastra) BARCLAYS BANK PLC BARC0INBB01 21/23, Maker Chambers VI, Nariman Point, Mumbai 400 021 BHARAT COOPERATIVE BANK BCBM0000999 Marutagiri, Plot No 13/9A,Sonawala Road,Samant Wadi,Goregaon LTD (e),Mumbai - 400 063 BK OF TOKYO MITSUBISHI UFJ BOTM0003611 JEEVAN VIHAR BUILDING, 3 PARLIAMENT STREET, NEW DELHI - LTD 110001 BNP PARIBAS BNPA0009066 French Bank Bldg.,62, Homji Street, Mumbai - 400 001 CALYON BANK CRLY0000001 Hoechst House, 11th, 12th, 14th Floor, Nariman Point, Churchgate, Mumbai - 400 021. -

Maha Eseva Kendra List

महा-ई-सेवा कᴂ 饍ा車ची यादी Sr. VLE Name Palghar CSC Address Location Pincode Mobile Maha E Sewa Kendra Nitin Bhaidas Rampur 1 Rampur Kosbad Road Near 401702 8237635961 Mothe (551636) Market Rampur Jayprakash Gholwad Gholwad Near 2 Ramchandra Gholwad 401702 9860891473 Jalaram Temple Gholwad Bari Bhika Bandu Parnaka Parnaka Parnaka Dahanu (M 3 401602 9637999157 Sonawane Dahanu Cl) Ganpat At-Haladpada Amboli 4 Sukhad Halapada 401606 9960227641 Shishane Road Haladpada Dhangda Nr Saideep Hospital At Post Malyan Tq Dhanu Amul Ramdas Dahanu (M 5 East Dist Thane-401602 401602 9967910609 Tandel Cl) Malyan Sai Deep Hospital Dahanu E Santosh Muskan S S Sanstha 6 Ramchandra 16,Sidhhi Complex,Kasa Kasa Kh. 401607 9049494194 Patil Dahanu Jawhar Road Gayatri Enterprizes, Muskan 16,Siddhicomplex, 7 Swayamrojgar 16,Siddhicomplex Dahanu Kasa Kh. 401607 9049494194 Seva Sahakari Jawhar Road Near Bank Of Maharashtra Kasa Jahir Kasim Maha E Seva Kendra 8 Vangaon 401103 9423533665 Shaikh Chinchani Road Vangaon Maha E Seva Kendra Jayvanti Dahanu (M 9 Dahanu Fort Near Ganesh 401601 9273039057 Rajendra Bari Cl) Mandir Tahsildar Office Maha E Seva Center Dhakti Dahanu Dhakti Dhakti 10 Kishor R Bari 401601 9860002524 Dahanu Bariwada Near Bus Dahanu Stop Maha E Seva Kendra Bordi Akshay 11 Shop No 511 Netaji Road Bordi 401701 8149107404 Bprakash Raut Opp Ram Mandir Bordi Muskan Maha E Seva Kendra 12 Swayamrojgar Ashagad 401602 7066822781 Ashagad Seva Sahakari Maha E-Seva Kendra 2 Prafful Dahanu-Vangaon Road 13 Jaywant Saravali 401602 8087930398 Near Savta Bridge Vaidya Ghungerpada At Dhundalwadi Darshana Dhundalwad 14 Dhundalwadi Talathi 401606 9765284663 Vilas Hilim i Office Ramij Kashim Maha E Seva Kendra 15 Aine 401103 9423533665 Shaikh Charoti Road Aina Maha E Seva Center Chinchani Vangaon Naka 01 Prathomasatv Bulding Chinchani 16 Kishor R Bari 401503 9860002524 Dahanu Khadi - Boisar (Ct) Road Near State Bank A.T.M. -

Maharastra State Electricity Distribution Co

Consumer Grievance Redressal Forum, Kalyan Zone Behind “Tejashree", Jahangir Meherwanji Road, Kalyan (West) 421301 Ph: – 2210707 & 2328283 Ext: - 122 IN THE MATTER OF GRIEVANCE NO.K/N/011/0101 OF 07-08 OF M/S KARSANDAS MAVJI KALYAN SHIL ROAD THANE REGISTERED WITH CONSUMER GRIEVANCE REDRESSAL FORUM KALYAN ZONE, KALYAN ABOUT INTERRUPTION OF SUPPLY M/s Karsandas Mavji (Here in after Kalyan Shil Road, Near Khidkali Mahadeo referred to Temple, Khidkali, Post Padele, Thane as consumer) Versus Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution (Here in after Company Limited through its Executive referred to Engineer East Division, Kalyan (E) as licensee) 1) Consumer Grievance Redressal Forum has been established under regulation of “Maharashtra Electricity Regulatory Commission Grievance No.K/N/011/0101 of 07-08 (Consumer Grievance Redressal Forum & Ombudsman) Regulation 2006” to redress the grievances of consumers. This regulation has been made by the Maharashtra Electricity Regulatory Commission vide powers conformed on it by section 181 read with sub-section 5 to 7 of section 42 of the Electricity Act, 2003. (36 of 2003). 2) The consumer is a H.T. consumer of the licensee connected to their 22 Kilo-volt network. Consumer is billed as per industrial tariff. The consumer registered grievance with the Forum on dated 04/05/2007. The details are as follows: - Name of the consumer: M/s Karsandas Mavji Address: - As above Consumer No: - 000239002439. Reason of dispute: - Interruption in supply 3) The batch of papers containing above grievance was sent by Forum vide letter No.0961 dated 04/05/07. The letter was replied by licensee vide letter dated 18/06/07. -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Runwal My City

https://www.propertywala.com/runwal-my-city-thane Runwal My City - Dombivli East, Thane Runwal My City - 1, 2 & 3 BHK apartments available for s… Runwal My City, Dombivli East, Thane (Maharashtra) Runwal My City presented by Runwal Group with 1, 2 & 3 BHK apartments available for sale in Dombivli (East), Thane Project ID : J609118997 Builder: Runwal Realty Completion Date: Sep, 2021 Status: Started Description Runwal My City is one of the residential development of Runwal Group. The project is located in Mumbai. It offers 1 BHK, 2 BHK and 3 BHK apartments. The project has been designed to facilitate perfect living conditions with optimum light, ventilation and privacy. The project is coupled with fresh and green surroundings, each apartment brings the joy of unhindered living. Units and Sizes:- 1 bhk:- 645 Sq. Ft 2 Bhk:- 770 Sq. Ft. 2 Bhk:- 840 Sq. Ft. 2 Bhk:- 860 Sq. Ft. 2 Bhk:- 870 Sq. Ft. 3 Bhk:- 1105 Sq. Ft. Project Details Total Area: 156 Acres Number of Floors: 27 Number of Towers: 10 Number of Units: 500 Amenities 24 Hr Backup Security Cafeteria Community Hall Swimming Pool Gymnasium Established in the year 1978, Runwal Realty is a leading real estate developer based in Mumbai. Mr. Subhash Runwal is the Chairman of the company and Sandeep Runwal and Subodh Runwal are the Directors. The primary business of the firm involves development of properties for residential and retail sectors. The company has developed more than 65 residential projects in the suburbs of Mumbai like Thane, Chembur, Mulund and Ghatkopar. Features Luxury Features -

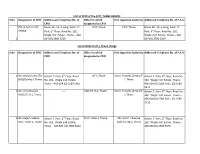

S.No Designation of CPIO Address and Telephone No. of CPIO Office

LIST of CPIO of The CCIT, THANE REGION S.No Designation of CPIO Address and Telephone No. of Office for which First Appellate Authority Address & Telephone No. of F.A.A. CPIO designated as CPIO ITO, H.Q O/o CCIT, Room No. 22, A-wing, Ashar I.T. CCIT, Thane CCIT, Thane Room No. 20, A-wing, Ashar I.T. THANE Park, 6th Floor, Road No. 16Z, Park, 6th Floor, Road No. 16Z, Wagle Indl. Estate, Thane – 400 Wagle Indl. Estate, Thane – 400 1 604 (O) 2580 5239 604 (O) 2580 5239 List of CPIO of CIT-I, Thane charge S.No Designation of CPIO Address and Telephone No. of Office for which First Appellate Authority Address & Telephone No. of F.A.A. CPIO designated as CPIO 1 Shri Manoj Sinha ITO Ashar I.T. Park, 6th Floor, Road CIT-I, Thane Shri K. Timothy Zimik CIT- Ashar I.T. Park, 6th Floor, Road No. (HQ)(Admn)-I, Thane No. 16Z, Wagle Indl. Estate, I, Thane 16Z, Wagle Indl. Estate, Thane – Thane – 400 604 (O) 2580 5466 400 604 (O) 2580 5411, (O) 2580 5410 2 Shri Anil Chaware ---- Addl.CIT, R-1, Thane Shri K. Timothy Zimik CIT- Ashar I.T. Park, 6th Floor, Road No. Addl.CIT, R-1, Thane I, Thane 16Z, Wagle Indl. Estate, Thane – 400 604 (O) 2580 5411, (O) 2580 5410 3 Shri Rajesh Meena Ashar I.T. Park, 6th Floor, Road ACIT, Circle-1, Thane Shri Anil P. Chaware Ashar I.T. Park, 6th Floor, Road No. ACIT, Circle-1, Thane No. -

Thane District NSR & DIT Kits 15.10.2016

Thane district UID Aadhar Kit Information SNO EA District Taluka MCORP / BDO Operator-1 Operator_id Operator-1 Present address VLE VLE Name Name Name Mobile where machine Name Mobile number working (only For PEC) number 1 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_akashS 7507463709 /9321285540 prithvi enterpriss defence colony ambernath east Akash Suraj Gupta 7507463709 Consultancy AMBARNATH thane 421502 Maharastra /9321285540 2 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_abhisk 8689886830 At new newali Nalea near pundlile Abhishek Sharma 8689886830 Consultancy AMBARNATH Maharastraatre school, post-mangrul, Telulea, Ambernath. Thane,Maharastra-421502 3 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_sashyam 9158422335 Plot No.901 Trivevi bhavan, Defence Colony near Rakesh Sashyam GUPta 9158422335 Consultancy AMBARNATH Ayyappa temple, Ambernath, Thane, Maharastra- 421502 4 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO abha_pandey 9820270413 Agrawal Travels NL/11/02, sector-11 ear Sandeep Pandey 9820270413 Consultancy AMBARNATH Ambamata mumbai, Thane,Maharastra-400706 5 Abha System and Thane Ambarnath BDO pahal_abhs 8689886830 Shree swami samath Entreprises nevalinaka, Abhishek Sharma 8689886830 Consultancy AMBARNATH mangrul, Ambarnath, Thane,Maharastra-421301 6 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS055808 9637755100/8422883379 Shop No.1, Behind Datta Mandir Durga Devi Pada Priyanka Wadekar 9637755100/ AMBARNATH /VLE_MCR610_NS073201 Old Ambernath, East 421501 8422883379 7 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS076230 9324034090 / Aries Apt. Shop No. 3, Behind Bethel Church, Prashant Shamrao Patil 9324034090 / AMBARNATH 8693023777 Panvelkar Campus Road, Ambernath West, 8693023777 421505 8 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS086671 9960261090 Shop No. 32, Building No. 1/E, Matoshree Nagar, Babu Narsappa Boske 9960261090 AMBARNATH Ambarnath West - 421501 9 Vakrangee LTD Thane Ambarnath BDO VLE_MH610_NS037707 9702186854 House No.