From Amphora to TEU: Journey of a Container

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mysteries of the Baratti Amphora

ISSN: 2687-8402 DOI: 10.33552/OAJAA.2019.01.000512 Open Access Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology Research Article Copyright © All rights are reserved by Vincenzo Palleschi The Mysteries of the Baratti Amphora Claudio Arias1, Stefano Pagnotta2, Beatrice Campanella2, Francesco Poggialini2, Stefano Legnaioli2, Vincenzo Palleschi2* and Cinzia Murolo3 1Retired Professor of Archaeometry, University of Pisa, Italy 2Institute of Chemistry of Organometallic Compounds, CNR Research Area, Pisa, Italy 3Curator at Museo Archeologico del Territorio di Populonia, Piazza Cittadella, Piombino, Italy *Corresponding author: Vincenzo Palleschi, Institute of Chemistry of Organometallic Received Date: April 22, 2019 Compounds, CNR Research Area, Pisa, Italy. Published Date: May 08, 2019 Abstract Since its discovery, very few certain information has been drawn about its history, provenience and destination. Previous archaeometric studies and the iconographyThe Baratti ofAmphora the vase is might a magnificent suggest asilver late antique vase, casually realization, recovered possibly in 1968 in an from Oriental the seaworkshop in front (Antioch). of the Baratti A recent harbor, study, in Southern performed Tuscany. by the National Research Council of Pisa in collaboration with the Populonia Territory Archaeological Museum, in Piombino, has led to a detailed study of the Amphora, both from a morphological point of view through the photogrammetric reconstruction of a high-resolution 3D model, and from the point of view of the analysis of the constituent -

Aspects of Ancient Greek Trade Re-Evaluated with Amphora DNA Evidence

Journal of Archaeological Science 39 (2012) 389e398 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Aspects of ancient Greek trade re-evaluated with amphora DNA evidence Brendan P. Foley a,*, Maria C. Hansson b,c, Dimitris P. Kourkoumelis d, Theotokis A. Theodoulou d a Department of Applied Ocean Physics and Engineering, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA b Center for Environmental and Climate Research (CEC), Lund University, 22362 Lund, Sweden c Department of Biology, Lund University, Ecology Building, 22362 Lund, Sweden d Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, Athens, Greece article info abstract Article history: Ancient DNA trapped in the matrices of ceramic transport jars from Mediterranean shipwrecks can reveal Received 29 March 2011 the goods traded in the earliest markets. Scholars generally assume that the amphora cargoes of 5the3rd Received in revised form century B.C. Greek shipwrecks contained wine, or to a much lesser extent olive oil. Remnant DNA inside 19 September 2011 empty amphoras allows us to test that assumption. We show that short w100 nucleotides of ancient DNA Accepted 23 September 2011 can be isolated and analyzed from inside the empty jars from either small amounts of physical scrapings or material captured with non-destructive swabs. Our study material is previously inaccessible Classical/ Keywords: Hellenistic Greek shipwreck amphoras archived at the Ministry of Culture and Tourism Ephorate of Greece Amphora Underwater Antiquities in Athens, Greece. Collected DNA samples reveal various combinations of olive, Ancient DNA grape, Lamiaceae herbs (mint, rosemary, thyme, oregano, sage), juniper, and terebinth/mastic (genus Shipwreck Pistacia). -

Landmarks Guide for Older Children

Landmarks Guide for Older Children Bryan Hunt American, born 1947 Amphora 1982 Bronze Subject: History Activity: Create a museum display for an object you use everyday Materials: An object from your home, pencil, and paper Vocabulary: Amphora, nonfunctional, obsolete, vessel Introduction An amphora is a type of clay vase with two handles that was used in ancient Greece. Thousands of years ago, these vessels served many purposes: They were used to store food, water, and wine. The vessels were often painted with figures that told stories about history and the gods. A person living in ancient Greece would sometimes have the same amphora throughout their lifetime. The Greeks did not have many other means for storing or transporting food and liquids, so amphorae were very important to them. These vessels, which were once a part of everyday life for the Greeks, are now kept in museums, where we can see them and learn about the people who used them. We no longer use large clay vessels like amphorae for our everyday needs. We use other types of containers instead. In making this sculpture, the artist was interested in exploring how the amphora and our ideas about it have changed over time. Notice that Hunt’s amphora is made of metal instead of clay; in other words, it is nonfunctional, and very different from a traditional Greek amphora. Questions What types of containers do we use What can these objects tell us about the today instead of amphorae? past and the people that lived then? Can you think of any other objects that What happens to objects when they were very useful to people in the past but are no longer useful to us? that are no longer useful to us today? Bryan Hunt, continued Activity Choose an object from your home that you use everyday. -

Containers January 2017 A) Origin Pre-Shipment Sampling

ECOM AGROINDUSTRIAL CORP. LTD. Best Practice Pre-shipment Instructions – Containers January 2017 A) Origin pre-shipment sampling: All testing to be carried out by appropriately qualified persons designated by ECOM at Seller’s cost. Equipment to be used for moisture testing is the ‘Aqua Boy’ for individual bags with a composite sample from each 25 MT lot to be tested using ‘Dickey John’. The moisture meters must be calibrated to “Tropical Conditions” and certified annually. 100% of bags must be tested for moisture levels by Aqua Boy probe test from every 25 MT lot immediately prior to stuffing into export container. If found to be over 7% moisture the bags are to be rejected. No bags having over 7% moisture can be loaded. (Please note that probe tests are considered to read 1% lower that cup tests so are less reliable) The party carrying out the testing will record and submit reports (format to be agreed by ECOM) of the results on a weekly basis to the Rekerdres claims manager – [email protected] B) Container inspections: External: There are to be minimum dents, no holes or splits. If present - reject. Look for International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) code labels and if present - reject the container. Look also for any indication of labels having been present / areas painted over on the sides of containers and if suspected – reject. Internal: No rust, foreign odours, foreign substances or dirty floors and if present - reject. Floor moisture levels to be checked in 9 areas throughout the container and if found to be above 12% at any testing point - reject. -

Answer Key the Safe Food Handler, Page 4-6

HACCP In Your School Answer Key The Safe Food Handler, Page 4-6 Can They Handle It? - For each situation, should the worker be working? No Sue has developed a sore throat with fever since coming to work. Sore throat with a fever is one of the five symptoms of foodborne illness and so the worker should be excluded from working in the establishment. Yes Cindy has itchy eyes and a runny nose. Itchy eyes and a runny nose are not symptoms of foodborne illness so Cindy would be able to work. However, each time Cindy wipes her eyes or her nose, she must properly wash her hands for 20 seconds using warm water, soap, and drying with a paper towel. No Tom vomited several times before coming to work. Tom cannot work because vomiting is a symptom of foodborne illness. Tom can return to work once the vomiting has stopped. If a medical professional determines that there is another reason for Tom’s vomiting that is not related to foodborne illness, Tom can work as long as he presents proper medical documentation. If the worker was a pregnant female, the vomiting would be determined to be due to morning sickness and so she could work. After each episode of vomiting, hands must be properly washed for 20 seconds using warm water, soap, and drying with a paper towel. No Juanita has had a sore throat for several days but still came to work today. Juanita cannot work because she has had a sore throat for several days and so the cause of the sore throat might be an infection. -

Wentzville R-Iv School District

WENTZVILLE R-IV SCHOOL DISTRICT 2021-2022 SCHOOL SUPPLY LIST Grades 4-6 3/31/21 GRADE 4 GRADE 5 GRADE 6 1 Box markers 4 Composition notebooks 1 Pair scissors (adult size) 1 Pkg. colored pencils* 3 Boxes facial tissue (girls only)* 48 #2 pencils 3 Pkgs. black dry erase markers 3 Pkgs. #2 yellow pencils - sharpened 1 Bottle white glue 3 Boxes facial tissue 1 Pkg. loose leaf paper (wide-rule) 1 Pkg. dry erase markers (4 pack)* 1 Pair scissors 1 Box markers 5 Glue sticks* 3 Glue sticks 1 Box colored pencils 1 Pkg. colored pencils* 3 Pkgs. #2 yellow pencils (24 ct.) sharpened 1 Box 24 ct. crayons 2 Highlighters* 1 1 ½” 3-ring binder (clear view front 1 Pair scissors (adult size) 1 Basic calculator w/pockets) 1 Pkg. of 3 glue sticks 1 Computer mouse 6 Two-pocket plastic/vinyl folders, 3-hole 6 Spiral notebooks (red, green, blue, yellow, 1 Zipper binder punched, solid colors orange and purple) 1 Roll paper towels 4 Spiral notebooks, 3-hole punched, solid 6 Two-pocket plastic/vinyl folders with prongs 2 Boxes facial tissue* colors (red, green, blue, yellow, orange and purple) 1 Pkg. 3”x5” index cards 1 Pkg. loose leaf paper, wide-rule 2 Pkgs. dry erase markers (4 or more per 1 Zipper pencil pouch for binder 3 Pkgs. sticky notes (3”x3”) pack) 1 Pkg. sticky notes (3”x3”) 1 Pink pencil eraser 1 1 ½” 3-ring binder (clear view front 1 Roll transparent tape 1 Roll paper towels w/pockets) 5 Composition notebooks 1 Box sandwich size zipper storage bags 6 Pkgs. -

Week 2 Packet

At Home Learning Resources Grade 7 Week 2 ELA Grades 5-8 At Home Learning Choices Weeks 2 & 3 You can continue the reading, writing, and vocabulary work from Week 1 OR continue online learning using tools like iReady, Lexia, Scholastic Learn OR complete the “Choose Your Own Adventure” Learning “Choose Your Own Adventure” This is a two week English Language Arts and Literacy exploration. Students will choose between 4 different options to pursue. Each option still requires daily reading. The goal of the project is to honor student growth and increase their learning with a project of their choice. There are different levels of independence, as well as choices for how to share their learning. (This work is borrowed from educator Pernille Ripp). Enjoy! So what are the choices? Choice To Do Choice 1: The Independent Reading Adventure See instructions below for “The Independent On this adventure, you will use a self-chosen fiction Reading Adventure” chapter book to show your reading analysis skills. Read and either write or record your answers to questions that show your deeper understanding of the text. Choice 2: The Picture Book Read Aloud See instructions below for “The Picture Book Read Adventure Aloud Adventure” On this adventure, you will listen to a picture book being read aloud every day by lots of wonderful people. Then you will write or record a response to a specific question every day. Choice 3: The Inquiry Project Adventure See instructions below for “The Inquiry Project Ever wanted a chance to pursue a major topic of Adventure” interest for yourself? Now is the chance. -

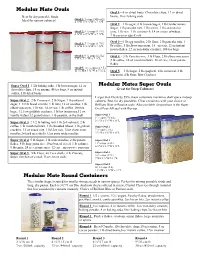

Modular Mates

Modular Mate Ovals Oval 1—8 oz dried fruits, Chocolate chips, 12 oz dried Best for dry pourable foods. beans, 16 oz baking soda Oval 1: 2-cups (500 mL) Ideal for narrow cabinets! 2 ¼"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L Oval 2—1 lb sugar, 2 lb brown Sugar, 1 lb Confectioners Sugar, 1 lb pancake mix, 1 lb raisins, 1 lb cornmeal or Oval 2: 4 ¾-cups (1.1 L) grits, 1 lb rice, 1 lb cornstarch, 18 oz cream of wheat, 4 ½"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L 1 lb cocoa or quick mix Oval 3—1 lb egg noodles, 2 lb flour, 2 lb pancake mix, 1 Oval 3: 7 ¼-cups (1.7 L) 6 ¾"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L lb coffee, 1 lb elbow macaroni, 18 oz oats, 12 oz instant potato flakes, 22 oz non-dairy creamer, 100 tea bags Oval 4: 9 ¾-cups (2.3 L) Oval 4 - 3 lb Pancake mix, 3 lb Flour, 2 lb elbow macaroni, 9"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L 2 lb coffee, 10 oz marshmallows, 60 oz rice, 16 oz potato flakes Oval 5: 12 ¼-cups (2.9 L) 11 ¼"H x 3 ¾"W x 7 ¼"L Oval 5— 5 lb Sugar, 5 lb spaghetti, 4 lb cornmeal, 3 lb macaroni, 4 lb flour, Ritz Crackers Super Oval 1 1 Lb baking soda, 1 lb brown sugar, 12 oz Modular Mates Super Ovals chocolate chips, 15 oz raisins, 40 tea bags, 8 oz instant Great for Deep Cabinets! coffee, 1 lb dried beans Larger than Ovals by 55%, these containers maximize shelf space in deep Super Oval 2 2 lb Cornmeal, 2 lb Sugar, 1 lb powered cabinets. -

2021 Concessions Catalog

MORE THAN A CUP.CUP PAGE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS About Us About Us Page 2 In-Mold Labeled IML Cups Pages 3 - 4 IMLS Cups Pages 5 - 6 Double Wall Cup Pages 7 - 8 Buckets Pages 9 - 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE Plastic Film Buckets Page 11 - 12 Boxes Pages 13 - 14 Lenticular 3D Lenticular 3D Cups Page 15 - 16 Heat Transferred Mason Jars Pages 17 - 18 Shakers & Carafes Pages 19 - 20 Dry Oset Printed Traditional Cups Page 21 - 22 Fluted Cups Page 23 - 24 Disposable Cups Page 25 - 26 Accessories Accessories Page 27 Sipper Lids Page 28 Added Value Specialty Options Page 29 Refill Programs Page 30 Augmented Reality Page 31 Why Reusable? Page 32 GENERAL GRAPHICS 800.999.5518 800.999.5518 [email protected] [email protected] JOE BLANDO MIKE JACOB Vice President of Sales National Sales Manager of Concessions 920.527.8326 785.749.1213 [email protected] [email protected] Download templates & upload artwork at churchillcontainer.com Call us at 800.999.5518 Connect with us ABOUT US Churchill Container designs and produces rigid plastic cups and containers for clients who value branded package design as a marketing tool. Since 1980, we’ve been helping promote brands and increase revenue with programs designed to drive repeat business. Our killer in-house art department is the best in the business and our single Midwest production facility enables us to provide consistent quality control and efficient tracking of orders. We offer an incredible array of options to raise the perceived value of any food or beverage product. -

Amphora™ 3D Polymer AM1800 Version 1.0 Revision Date: 02/17/2016

Safety Data Sheet Amphora™ 3D Polymer AM1800 Version 1.0 Revision Date: 02/17/2016 SECTION 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : Amphora™ 3D Polymer AM1800 Recommended use of the chemical and restrictions on use Recommended use : Thermoplastic Resin Supplier or Repackaging Details Company : Nexeo Solutions, LLC. Address 3 Waterway Square Place Suite 1000 The Woodlands, TX. 77380 United States of America Manufactured By : Eastman Chemical Company Emergency telephone number: Health North America: 1-855-NEXEO4U (1-855-639-3648) Health International: 1-855-NEXEO4U (1-855-639-3648) Transport North America: CHEMTREC (1-800-424-9300) Additional Infor- : Responsible Party: Product Safety Group mation: E-Mail: [email protected] SDS Requests: 1-855-429-2661 SDS Requests Fax: 1-281-500-2370 Website: www.nexeosolutions.com SECTION 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION GHS Classification This material is considered hazardous under the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard criteria, based on hazard(s) not otherwise classified. GHS Label element Signal word : Warning Hazard statements : May form combustible dust concentrations in air Potential Health Effects Carcinogenicity: IARC No component of this product present at levels greater than or equal to 0.1% is identified as probable, possible or confirmed human carcinogen by IARC. ACGIH No component of this product present at levels greater than or equal to 0.1% is identified as a carcinogen or potential carcinogen by ACGIH. OSHA No component of this product present at levels greater SDS Number: 100000022948 1 / 12 Amphora™ 3D Polymer AM1800 Safety Data Sheet Amphora™ 3D Polymer AM1800 Version 1.0 Revision Date: 02/17/2016 than or equal to 0.1% is identified as a carcinogen or potential carcinogen by OSHA. -

Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA

Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA Edited by Peter Anderson, Fleur Braddick, Jillian Reynolds and Antoni Gual Edited by: Peter Anderson, Fleur Braddick, Jillian Reynolds & Antoni Gual 2012 The AMPHORA project has received funding from the European Commission's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007‐2013) under grant agreement nº 223059 ‐ Alcohol Measures for Public Health Research Alliance (AMPHORA). Participant organisations in AMPHORA can be seen at http://www.amphoraproject.net/view.php?id_cont=32. The contents of each chapter are solely the responsibility of the corresponding authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the European Commission or of the editors. How to cite this ebook: Anderson P, Braddick F, Reynolds J & Gual A eds. (2012) Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA. The AMPHORA project, available online: http://amphoraproject.net/view.php?id_cont=45 Alcohol Policy in Europe Contents CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................iii ABOUT THE AUTHORS AND EDITORS ................................................................................. iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION Antoni Gual & Peter Anderson .......................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 2. WHAT ALCOHOL CAN DO TO EUROPEAN SOCIETIES Jürgen Rehm ..................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 3. DOES ALCOHOL POLICY -

Amphora-Aged Cos Wine: New Or Ancient

AMPHORA-AGED COS WINE: NEW OR ANCIENT There is something simply amazing to view a winery making its top wines in a series of earthenware jars. Is there shock-horror? Yes for a technocrat trained on the finer points of grades of stainless steel. But no for someone on a path of discovery to understand just what the practitioners do when there is a choice to return to the roots of winemaking practice. And the use of clay pots has been a natural winemaking event year-on-year in Georgia for as far back as 6000 years BC. Recently a colleague advised me that a 2012 trip to this old world winemaking country included a visit to a monastery using the clay pot containers continuously for 1000 years (a lot of vintages there to build up tartrate!) So I was recently on the path of discovery in Sicily to visit two famous properties using earthenware jars for winemaking and aging (COS in Vittoria) and Cornelissen (on Etna) who ages new wine similarly. There is a space in between with the technology path-that of using oak barrels as storage vessels, and over the past decade used, large (3-5,000 litre) format casks have proved to be valuable aging means for high quality wines. Casks displaced earthenware vessels as they were more practical. However keeping large casks fresh and clean is a never-ending job, and at times capable of going wrong (cask has to be burnt). Also the cask remains practical for making larger volumes of wine, while re-introducing the clay pot makes sense for small parcel winemaking as pot management is a lot simpler than in the 15th century.