Custody Evaluations When There Are Allegations of Domestic Violence: Practices, Beliefs, and Recommendations of Professional Evaluators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behaviour and Characteristics of Perpetrators of Online-Facilitated Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation a Rapid Evidence Assessment

Behaviour and Characteristics of Perpetrators of Online-facilitated Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation A Rapid Evidence Assessment Final Report Authors: Jeffrey DeMarco, Sarah Sharrock, Tanya Crowther and Matt Barnard January 2018 Prepared for: Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) Disclaimer: This is a rapid evidence assessment prepared at IICSA’s request. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. At NatCen Social Research we believe that social research has the power to make life better. By really understanding the complexity of people’s lives and what they think about the issues that affect them, we give the public a powerful and influential role in shaping decisions and services that can make a difference to everyone. And as an independent, not for profit organisation we’re able to put all our time and energy into delivering social research that works for society. NatCen Social Research 35 Northampton Square London EC1V 0AX T 020 7250 1866 www.natcen.ac.uk A Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England No.4392418. A Charity registered in England and Wales (1091768) and Scotland (SC038454) This project was carried out in compliance with ISO20252 © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.iicsa.org.uk. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] Contents Glossary of terms ............................................................. -

Motivations and Impression Management

MOTIVATIONS AND IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT: PREDICTORS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING SITE USE AND USER BEHAVIOR A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by Kara Krisanic Dr. Shelly Rodgers, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled MOTIVATIONS AND IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT: PREDICTORS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING SITE USE AND USER BEHAVIOR presented by Kara Krisanic, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Shelly Rodgers, Committee Chair ________________________________________ Dr. Margaret Duffy, Committee Member and Advisor ________________________________________ Dr. Paul Bolls, Committee Member ________________________________________ Dr. Jennifer Aubrey, Outside Committee Member ________________________________________ DEDICATION I dedicate the following thesis to my parents, Rita and Julius, without whom nothing in my life would be possible. Your love, encouragement, support and guidance have always served as the driving force behind my motivation to achieve my highest goals. Words cannot express the overwhelming gratitude I have for the life you have provided me. I will forever carry with me, the lessons you have instilled in my heart. Thank you and I love you, yesterday, today and always. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my entire thesis committee for their gentle guidance, continuous mentoring, and undying support throughout the completion of my thesis and graduate degree. Each of your unique contributions encouraged me to reach further and to dig deeper than I ever thought myself capable. -

Tactics of Impression Management: Relative Success on Workplace Relationship Dr Rajeshwari Gwal1 ABSTRACT

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (e) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (p) Volume 2, Issue 2, Paper ID: B00362V2I22015 http://www.ijip.in | January to March 2015 Tactics of Impression Management: Relative Success on Workplace Relationship Dr Rajeshwari Gwal1 ABSTRACT: Impression Management, the process by which people control the impressions others form of them, plays an important role in inter-personal behavior. All kinds of organizations consist of individuals with variety of personal characteristics; therefore those are important to manage them effectively. Identifying the behavior manner of each of these personal characteristics, interactions among them and interpersonal relations are on the basis of the impressions given and taken. Understanding one of the important determinants of individual’s social relations helps to get a broader insight of human beings. Employees try to sculpture their relationships in organizational settings as well. Impression management turns out to be a continuous activity among newcomers, used in order to be accepted by the organization, and among those who have matured with the organization, used in order to be influential (Demir, 2002). Keywords: Impression Management, Self Promotion, Ingratiation, Exemplification, Intimidation, Supplication INTRODUCTION: When two individuals or parties meet, both form a judgment about each other. Impression Management theorists believe that it is a primary human motive; both inside and outside the organization (Provis,2010) to avoid being evaluated negatively (Jain,2012). Goffman (1959) initially started with the study of impression management by introducing a framework describing the way one presents them and how others might perceive that presentation (Cole, Rozelle, 2011). The first party consciously chooses a behavior to present to the second party in anticipation of a desired effect. -

Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations College of Science and Health Summer 8-20-2017 Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression Anthony S. Colaneri DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Colaneri, Anthony S., "Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression" (2017). College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations. 232. https://via.library.depaul.edu/csh_etd/232 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Science and Health at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Science and Health Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS Proactive Workplace Bullying in Teams: Test of a Rational and Moral Model of Aggression A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Anthony S. Colaneri 7/4/2017 Department of Psychology College of Science and Health DePaul University Chicago, Illinois PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS ii Thesis Committee Suzanne Bell, Ph.D., Chairperson Douglas Cellar, PhD., Reader PROACTIVE WORKPLACE BULLYING IN TEAMS iii Acknowledgments I would like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Dr. Suzanne Bell for her invaluable guidance and support throughout this process. I would also like to thank Dr. Douglas Cellar for his guidance and added insights in the development of this thesis. -

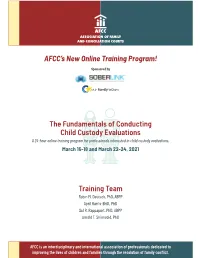

The Fundamentals of Conducting Child Custody Evaluations AFCC's

ASSOCIATION OF FAMILY AND CONCILIATION COURTS AFCC’s New Online Training Program! Sponsored by The Fundamentals of Conducting Child Custody Evaluations A 24-hour online training program for professionals interested in child custody evaluations. March 16-18 and March 22-24, 2021 Training Team Robin M. Deutsch, PhD, ABPP April Harris-Britt, PhD Sol R. Rappaport, PhD, ABPP Arnold T. Shienvold, PhD AFCC is an interdisciplinary and international association of professionals dedicated to improving the lives of children and families through the resolution of family conflict. The Fundamentals of Conducting Child Custody Evaluations A 24-hour online training program for professionals interested in child custody evaluations. March 16-18 and March 22-24, 2021 AFCC is pleased to introduce a new, comprehensive child custody evaluation (CCE) training, conducted online by a team of leading practitioners and trainers. The program will take place in two segments per day, two hours each. Recordings of all sessions will be available for registrants. This program will include a complete overview of the child custody evaluation process, including: Definition of the purpose and roles of the child custody evaluator Specifics of the evaluation process, including interviewing, recordkeeping, and use of technology Implications of intimate partner violence and resist-refuse dynamics Updates on the current research Development of parenting plans Review of cultural considerations, bias, and ethical issues Utilization of psychological testing Best practices for report writing and testifying Participants will learn the difference between a forensic role and clinical role, how to review court orders and determine which information should be obtained, strategies for interviewing adults and children, how to assess coparenting issues, how to develop and test multiple hypotheses, and how to craft recommendations. -

Impression Management and Its Interaction with Emotional Intelligence and Locus of Control: Two-Sample Investigation

R M B www.irmbrjournal.com September 2016 R International Review of Management and Business Research Vol. 5 Issue.3 I Impression Management and Its Interaction with Emotional Intelligence and Locus of Control: Two-Sample Investigation TAREK A. EL BADAWY Assistant Professor of Management, Auburn University at Montgomery, Alabama. Email: [email protected] ISIS GUTIÉRREZ-MARTÍNEZ Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Santa Catarina Mártir S/N. Email: [email protected] MARIAM M. MAGDY Research Associate, German University in Cairo, Egypt. Email: [email protected] Abstract The art of self-presentation is inherently important for exploration. Tight markets and fierce competition force employees to think about presenting themselves in the best way that ensures their continuous employment. In this study, an attempt was made to compare between employees of Mexico and Egypt with regard to the types of impression management strategies they use. Interactions between impression management, emotional intelligence and locus of control were also investigated. Several significant insights were reached using the Mann-Whitney U test. Further analyses, implications and future research recommendations are provided. Key Words: Self-Presentation; Emotions; Perception; Comparative Study; Middle East; Latin America. Introduction Impression management or the technique of self-presentation was the term first introduced by Goffman in the 1950s. Impression management is the individual’s attempt to manipulate how others see him/her as if the individual is an actor on stage trying to convey a certain character to the spectators. Originally a construct in Psychology, scholars of organizational behaviour adopted it in their pursuit to understand the different complicated relationships between employees in organizations (Ashford and Northcraft, 1992; Leary and Kowalski, 1990). -

GUIDELINES for CHILD CUSTODY EVALUATIONS in DIVORCE PROCEEDINGS American Psychologist © 1994 by the American Psychological Association July 1994 Vol

APPENDIX B GUIDELINES FOR CHILD CUSTODY EVALUATIONS IN DIVORCE PROCEEDINGS American Psychologist © 1994 by the American Psychological Association July 1994 Vol. 49, No. 7, 677-680 For personal use only--not for distribution. Guidelines for Child Custody Evaluations in Divorce Proceedings Correspondence may be addressed to the Practice Directorate, American Psychological Association, 750 First Street, NE, Washington, DC, 20002-4242. Introduction Decisions regarding child custody and other parenting arrangements occur within several different legal contexts, including parental divorce, guardianship, neglect or abuse proceedings, and termination of parental rights. The following guidelines were developed for psychologists conducting child custody evaluation, specifically within the context of parental divorce. These guidelines build upon the American Psychological Association's Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct ( APA, 1992 ) and are aspirational in intent. As guidelines, they are not intended to be either mandatory or exhaustive. The goal of the guidelines is to promote proficiency in using psychological expertise in conducting child custody evaluations. Parental divorce requires a restructuring of parental rights and responsibilities in relation to children. If the parents can agree to a restructuring arrangement, which they do in the overwhelming proportion (90%) of divorce custody cases ( Melton, Petrila, Poythress, & Slobogin, 1987 ), there is no dispute for the court to decide. However, if the parents are unable to reach such an agreement, the court must help to determine the relative allocation of decision making authority and physical contact each parent will have with the child. The courts typically apply a "best interest of the child" standard in determining this restructuring of rights and responsibilities. -

THE EXPERIENCE and PROCESS of IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT in CLINICAL SUPERVISION Ariel Heather Goodman

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2019 SAVING FACE: THE EXPERIENCE AND PROCESS OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT IN CLINICAL SUPERVISION Ariel Heather Goodman Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Goodman, Ariel Heather, "SAVING FACE: THE EXPERIENCE AND PROCESS OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT IN CLINICAL SUPERVISION" (2019). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11353. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11353 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT AND SUPERVISION SAVING FACE: THE EXPERIENCE AND PROCESS OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT IN CLINICAL SUPERVISION By ARIEL HEATHER GOODMAN M.A. in Counseling, Johnson State College, Johnson, VT, 2015 B.A. in Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 2008 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Counselor Education and Supervision The University of Montana Missoula, MT May, 2019 Approved by: Kirsten W. Murray, Ph.D., Chair Counselor Education Veronica Johnson, Ed.D. Counselor Education Sara Polanchek, Ed.D. Counselor Education John Sommers-Flanagan, Ph.D. Counselor Education Daisy Rooks, Ph.D. Sociology IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT AND SUPERVISION Goodman, Ariel, Ph.D., Spring 2019 Counselor Education and Supervision Abstract Chairperson: Kirsten W. Murray, Ph.D. -

Refrainment from Impression Management Behavior Despite High Impression Motivation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Wharton Research Scholars Wharton Undergraduate Research 5-12-2015 Respect: Refrainment From Impression Management Behavior Despite High Impression Motivation Jung Ho James An University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars Part of the Business Commons An, Jung Ho James, "Respect: Refrainment From Impression Management Behavior Despite High Impression Motivation" (2015). Wharton Research Scholars. 125. https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars/125 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/wharton_research_scholars/125 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Respect: Refrainment From Impression Management Behavior Despite High Impression Motivation Abstract We sometimes unintentionally distance ourselves from the people we respect. In a relationship between two individuals of perceived unequal status, what are the behaviors or factors of the person of lower status that distance him or her from the person he or she respects? Impression management is the process by which people control their impressions others form of them (Leary & Kowalski, 1990), and can be a useful theory in explaining this phenomenon; however, it does not explain the entire story. This is one possible instance in which we have high impression motivation but refrain from impression management behavior. This project aims to shed light on the nature and causes of refrainment from impression management behavior despite high impression motivation by exploring the factors that cause people to distance themselves from the people that they respect and perceive to have higher status and power. This research focuses on the distancing factors surrounding the person of the lower status. -

A Critical Examination of the Suitability and Limitations of Psychological Tests in Family Court

PSYCHOLOGICALBlackwellMalden,FCREF1531-2445©April452OriginalErickson,FAMILYamily Association 2007 Court Article USACOURT LilienfeldPublishing Review of Family REVIEW and Inc andVitacco/A Conciliation CRITICAL Courts, EXAMINATION 2007 OF THE SUITABILITY and LIMITATIONS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS TESTING IN FAMILY COURT AND CHILD CUSTODY EVALUATIONS IN FAMILY COURT: A DIALOGUE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE SUITABILITY AND LIMITATIONS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS IN FAMILY COURT Steven K. Erickson Scott O. Lilienfeld Michael J. Vitacco Psychologists are frequently consulted by the courts to provide forensic evaluations in a variety of family court proceedings. As part of their evaluations, psychologists often use psychological tests to assess parents, guardians, and children. These tests can have profound effects on how psychologists arrive at their opinions and are often cited in their reports to the court. However, psychological tests vary substantially in their suitability for these purposes. Most projective tests in particular appear to possess little scientific merit for evaluations within family court proceedings. Despite these serious limitations, expert testimony derived from evaluations using both projective and objective tests is often admitted uncontested. This article reviews the psychometric properties of psychological tests that are widely used in family court proceedings, cautions against their unfettered use, and calls upon attorneys to inform themselves of the limitations of evaluations that incorporate these tests. Keywords: child -

Impression Mismanagement: People As Inept Self-Presenters

Received: 19 October 2016 Revised: 20 April 2017 Accepted: 22 April 2017 DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12321 ARTICLE Impression mismanagement: People as inept self‐presenters Janina Steinmetz1 | Ovul Sezer2 | Constantine Sedikides3 1 Utrecht University, Netherlands Abstract 2 Harvard Business School, USA People routinely manage the impressions they make on others, 3 University of Southampton, UK attempting to project a favorable self‐image. The bulk of the litera- Correspondence ‐ Janina Steinmetz, Social and Organisational ture has portrayed people as savvy self presenters who typically Psychology, Utrecht University, succeed at conveying a desired impression. When people fail at Heidelberglaan 1, 3584 CS Utrecht, making a favorable impression, such as when they come across as Netherlands. braggers, regulatory resource depletion is to blame. Recent Email: [email protected] research, however, has identified antecedents and strategies that foster systematic impression management failures (independently of regulatory resource depletion), suggesting that self‐presenters are far from savvy. In fact, they commonly mismanage their impres- sions without recognizing it. We review failed perspective taking and narcissism as two prominent antecedents of impression mismanagement. Further, we argue that failed perspective taking, exacerbated by narcissism, contributes to suboptimal impression management strategies, such as hubris, humblebragging, hypocrisy, and backhanded compliments. We conclude by discussing how self‐presenters might overcome some of the common traps of impression mismanagement. “All the world's a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances …” —William Shakespeare, “As You Like It, Act II, Scene VII” 1 | INTRODUCTION Self‐presentation is an integral part of social life. -

Use of Impression Management Strategies in Response to a Feedback

USE OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES IN RESPONSE TO A FEEDBACK INTERVENTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Jacob Scott Nelson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Communication May 2019 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title Use of Impression Management Strategies in Response to a Feedback Intervention By Jacob Scott Nelson The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Catherine Kingsley Westerman Chair Pamela Emanuelson Justin Walden Approved: 5/21/2019 Stephenson Beck Date Department Chair ABSTRACT Providing performance feedback in a way that leads to improved performance is an integral aspect to the success of an organization. Past research shows the feedback does not always improve employee performance. Characteristics of feedback can direct attention away from improved performance and toward attention to the self. This study examined the impact of characteristics of feedback delivery on individuals’ tendency to use impression management strategies (exemplification, self-promotion, ingratiation, supplication). The results indicate that participants did not use impression management differently when feedback was delivered publicly versus privately. However, participants reported a higher likelihood to use ingratiation and self-promotion strategies after receiving negative than positive feedback. Discussion of results, along with limitations and directions for future research, are discussed. Keywords: impression management, feedback intervention, privacy, valence iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to recognize his thesis committee Dr.