The Professionalisation of British Darts, 1970 – 1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton District Darts Association Inc Rules of Play

HAMILTON DISTRICT DARTS ASSOCIATION INC RULES OF PLAY Amended 2nd March 2020 Hamiltondarts.org.au [email protected] Hamilton District Darts Association Rules of Play Amended 2nd March 2020 CONTENTS CLAUSE No: PAGE No: ------ Contents 1 1. The Board 2 2. Stance 3 3. Composite of Games 4 4. Starting Time 4 5 Prior to Start of Play 5 6 Start of Play 5 7 Scoring Dart 6 8 The Dart 6 9 Scoring 6 10 Score Enquires 6 11 Playing Short 7 12 Player Running Late 7 13 Early Closure of Venue 8 14 Points System 8 15 Protests 8 16 Appeals 9 17 Forfeits 9 18 Count Back 9 19 Result Sheets 10 20 Venues 11 21 Finals 11 22 Dress 11 23 Trophy Entitlements 11 24 Conduct 12 25 Promotion/Relegation 12 26 Sponsorship 12 27 Junior Players 13 1 Hamilton District Darts Association Rules of Play Amended 2nd March 2020 1. THE BOARD: 1.1 All competition games shall be played on a standard 46cm (18”) bristle type board of reputable manufacture and approved By the Darts Federation of Australia. The board must be in good playable condition with segments clearly defined. 1.2 Lighting on all boards shall be suitably illuminated with no shadows. All lighting shall be shaded from the players eyes. 1.3 The board must be at a height of 173cm (5’ 8”) from the centre of the bullseye to the floor. The oche line shall be 2.370 metres (7’ 9 ¼”) from the point on the floor directly below the bullseye to the oche line. -

The Unicorn Book of Darts 2008

THE BOOK OF DARTS 2008 TO OUR CUSTOMERS.... standard packs. The standard pack has been selected for ease of stocking Our aim is to make trading with and ordering, economy in production Unicorn easy and to ensure safe transit of the We try very hard to have an contents. For these reasons we cannot appreciation of our customers’ split standard packs and where orders problems and to have a minimum call for other than standard packs we of rules shall adjust the order to the nearest We feel the stating of our policies will pack quantity make it easier and more profitable for our customers to deal with Unicorn 6. GUARANTEE It is our aim to ensure the complete 1. WARNING satisfaction of our customers and in DARTS IS AN ADULT SPORT. IT IS case of a genuine complaint as to the DANGEROUS FOR CHILDREN TO quality of our goods, we shall be PLAY WITHOUT SUPERVISION. WE anxious to rectify any fault of our own RECOMMEND THAT A DEALER free will and at our discretion only SHOULD EXERCISE DISCRETION WHERE ANY SALE MIGHT RESULT 7. IMITATIONS IN CHILDREN PLAYING WITHOUT The design, construction and trade ADULT SUPERVISION names of most of our products are protected by patents, design 2. DISTRIBUTION registrations, trade marks, copyrights We are geared to supply goods to and/or pending applications and accredited retailers only and thus rigorous action will be taken against cannot give satisfaction to clubs or all infringers to protect both dealer individuals, whom we refer to local and users from imitation dealers, anxious and ready to provide a prompt and complete service 8. -

SM-Liiga Saatiin Päätökseen Tulevaisuudesta

SM-liiga saatiin päätökseen Tulevaisuudesta retkieväin ei ole eikä sitä hallituksen nykyi- lutuksia ja muita häiriötekijöitä. Helpottaa sellä kokoonpanolla saada ikinä aikaan. Ei kaikkien kisaan osallistuvien päivää. hallituksen itse sitä ajatushautomoa tarvitse käydä läpi, vaan hoitaa sekin puoli omista Kilpailuiden pituus velvollisuuksistaan liitoa kohtaan. Kisapäivät alkavat olla liian pitkiä niin pe- Siksi syksyn kokouksessa on ensiarvoi- laajien kuin kisajärjestäjien kannalta. 12- sen tärkeää, että mukaan tulisi joku, jol- 14 tuntia on työ- tai kisapäivän pituudeksi la on aikaa ottaa tämä sarka hoitaakseen. aivan liikaa huonoilla yöunilla. Pelipäiväs- Oma näkemykseni on että hän ei saa olla sä saisi olla vain yksi pääsarja ja mahdolli- puheenjohtaja, koska olemme vahvasti pj- set B- sekä ikäkausisarjat. vetoinen liitto käytännön tasolla. Valitta- Jos kisamaksu on 35 euroa sisältäen pää- va puheenjohtaja joutuu tekemään paljon sarjan ja B-kisan, joka olisi 1. ja 2. kierrok- rutiiniasioita eikä silloin ole aikaa kehitel- sen pudonneille, niin yhdessä ennakkoil- lä uusia kuvioita. moittautumisen ja kisan aikataulutuksen Tietynlainen kylähullu ja Pelle Peloton kanssa koko kisapaketista saadaan paketti, tarvitaan hallituksen jäsenen asemassa rik- joka toimisi omaan tahtiinsa eikä rasittaisi Risto Spora komaan tuttuja latuja. Annetaan hänelle pelaajia eikä toimitsijoita. valtuudet miettiä uutta tapaa lähestyä tä- Ja kun meillä on käytössä ennakkoil- tä yksinkertaista lajia monikulmasta jopa moittautuminen, niin 1. kierroksen pudon- kierteellä nurkan takaa. nut näkee kaaviosta mihin kohtaa pääkisan Viime lehden jälkeen olin jo Huolestuttavaa on, ettei puheenjohta- po. ottelun hävinnyt menee ja tietää näin ajatellut että tämä nyt käsissä- juudesta ole käyty minkäänlaista keskuste- heti koska pelaa ”Looser Cupin” ottelunsa. si oleva lehti on viimeinen jon- lua viime vuosina. -

Darts Quiz Questions

Darts Big Quiz So, you think you know Darts? Here is a list of question for the dart related questions, how many can you get correct? written by David King QUESTIONS (MULTIPLE CHOICE) 1) Where was the first BDO World Champions held? A. Lakeside B. Alexandra Palace C. Heart of Midlands Club D. Jollees Club, Stoke-on-Trent 2) Name the three darts players who have received an MBE? A. Bristow, Lowe, Taylor B. Bristow, Gulliver, Lowe C. Ashton, Bristow, George D. Wilson, Taylor, Priestley 3) Which dart player walks onto ‘I’m too sexy’ by Right Said Fred? A. Andy Fordham B. Devon Peterson C. Deta Hedman D. Steve Beaton 4) What is Dennis Nilsson’s nickname? A. The Sheriff B. Rocky C. Excalibur D. Iron Man 5) Who had the first 100 plus televised average score? A. Eric Bristow B. John Lowe C. Keith Deller D. Phil Taylor 6) Over the last 100 years, dartboards have been commercially made and sold using four different types of material. Excluding, the plastic used in the construction of soft-tip dartboards can you name four? A. wood, clay, paper, sisal B. straw, paper, wood, pig bristle C. horse hair, wood, straw, pig bristle D. cotton, MDF, foam, compressed fur 7) What is the highest three-dart average that can be scored in a single leg of 501 double finish? A. 132 B. 147 C. 152 D. 167 8) James Wade holds a World record for hitting the most inner and outer bullseyes in 60 seconds on a standard dartboard, throwing from a normal oche length 2.37M. -

This Is a Terrific Book from a True Boxing Man and the Best Account of the Making of a Boxing Legend.” Glenn Mccrory, Sky Sports

“This is a terrific book from a true boxing man and the best account of the making of a boxing legend.” Glenn McCrory, Sky Sports Contents About the author 8 Acknowledgements 9 Foreword 11 Introduction 13 Fight No 1 Emanuele Leo 47 Fight No 2 Paul Butlin 55 Fight No 3 Hrvoje Kisicek 6 3 Fight No 4 Dorian Darch 71 Fight No 5 Hector Avila 77 Fight No 6 Matt Legg 8 5 Fight No 7 Matt Skelton 93 Fight No 8 Konstantin Airich 101 Fight No 9 Denis Bakhtov 10 7 Fight No 10 Michael Sprott 113 Fight No 11 Jason Gavern 11 9 Fight No 12 Raphael Zumbano Love 12 7 Fight No 13 Kevin Johnson 13 3 Fight No 14 Gary Cornish 1 41 Fight No 15 Dillian Whyte 149 Fight No 16 Charles Martin 15 9 Fight No 17 Dominic Breazeale 16 9 Fight No 18 Eric Molina 17 7 Fight No 19 Wladimir Klitschko 185 Fight No 20 Carlos Takam 201 Anthony Joshua Professional Record 215 Index 21 9 Introduction GROWING UP, boxing didn’t interest ‘Femi’. ‘Never watched it,’ said Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua, to give him his full name He was too busy climbing things! ‘As a child, I used to get bored a lot,’ Joshua told Sky Sports ‘I remember being bored, always out I’m a real street kid I like to be out exploring, that’s my type of thing Sitting at home on the computer isn’t really what I was brought up doing I was really active, climbing trees, poles and in the woods ’ He also ran fast Joshua reportedly ran 100 metres in 11 seconds when he was 14 years old, had a few training sessions at Callowland Amateur Boxing Club and scored lots of goals on the football pitch One season, he scored -

RULES and REGULATIONS of the WESTERN CAROLINA DARTS ASSOCIATION ASHEVILLE, NC

RULES AND REGULATIONS of the WESTERN CAROLINA DARTS ASSOCIATION ASHEVILLE, NC Approved: 2 October 1989 Amended: 8 June 2009, 27 June 09, 18 August 2010, 04 February 2012, 21 July 2012, 12 Jan 2013 PREFACE The RULES and REGULATIONS of the WCDA comprise the foundation which the sport of darts will be organized and developed as a team sport in the Western North Carolina area. Their acceptance and enforcement are essential to the growth of the game of darts to a place on the list of legitimate sports in the area. The WCDA is a social organization formed to promote darting as a sporting, recreational and social activity. The RULES and REGULATIONS, herein referred to as the “RULES,” of the WCDA are based upon the rules of darts, good sportsmanship, and common sense. To abide by the rules is to improve the game, not to distract from it or damage it. Adherence to the rules will serve to place all players and teams on even ground, and is to the advantage of all players, teams, pub owners and sponsors. An official copy of the RULES will be provided to each team sponsor annually after the current dues and sponsor fees are paid. These rules apply to all leagues in the WCDA. The RULES and REGULATIONS of the American Darts Organization should be referred to if not covered herein. ARTICLE I RULES & GRIEVANCE COMMITTEE 1. Cooperation and sportsmanship are preferable to enforcement. Enforcement, when necessary, is the responsibility of the RULES and GRIEVANCE COMMITTEE, herein referred to as the “COMMITTEE.” The COMMITTEE will interpret and enforce the Rules of the WCDA, continue to represent the association in a favorable manner and continue to serve the best interest of the association and its members and sponsors. -

BDO Darts-WM 1978-2019 Tabellen Und Ergebnisse

BDO Darts-Weltmeisterschaft 1978 - 2019 1978 1979 1. Leighton REES 1. John LOWE 2. John LOWE 2. Leighton REES 3. Nicky VIRACHKUL 3. Tony BROWN 4. Stefan LORD 4. Alan EVANS 1980 1981 1. Eric BRISTOW 1. Eric BRISTOW 2. Bobby GEORGE 2. John LOWE 3. Tony BROWN 3. Cliff LAZARENKO 4. Cliff LAZARENKO 4. Tony BROWN 1982 1983 1. Jocky WILSON 1. Keith DELLER 2. John LOWE 2. Eric BRISTOW 3. Stefan LORD 3. Jocky WILSON 4. Bobby GEORGE 4. Tony BROWN 1984 1985 1. Eric BRISTOW 1. Eric BRISTOW 2. Dave WHITCOMBE 2. John LOWE 3. John LOWE 3. Dave WHITCOMBE 4. Jocky WILSON 4. Cliff LAZARENKO 1986 1987 1. Eric BRISTOW 1. John LOWE 2. Dave WHITCOMBE 2. Eric BRISTOW 3. Alan GLAZIER 3. Jocky WILSON 4. Bob ANDERSON 4. Alan EVANS 1988 1989 1. Bob ANDERSON 1. Jocky WILSON 2. John LOWE 2. Eric BRISTOW 3. Rick NEY 3. Bob ANDERSON 4. Eric BRISTOW 4. John LOWE 1990 1991 1. Phil TAYLOR 1. Dennis PRIESTLEY 2. Eric BRISTOW 2. Eric BRISTOW 3. Cliff LAZARENKO 3. Bob ANDERSON 4. Mike GREGORY 4. Kevin KENNY 1992 1993 1. Phil TAYLOR 1. John LOWE 2. Mike GREGORY 2. Alan WARRINER 3. John LOWE 3. Bobby GEORGE 4. Kevin KENNY 4. Steve BEATON 1994 1995 1. John PART 1. Richie BURNETT 2. Bobby GEORGE 2. Raymond van BARNEVELD 3. Ronnie SHARP 3. Andy FORDHAM 4. Magnus CARIS 4. Martin ADAMS 1996 1997 1. Steve BEATON 1. Les WALLACE 2. Richie BURNETT 2. Marshall JAMES 3. Andy FORDHAM 3. Mervyn KING 4. -

Kausi Käyntiin, Sami Mondolin Mestariksi Sivu 15 Matkalla Tulevaisuuteen Tätä Lukiessanne on Uusi Liittohallitus Valittu

Kausi käyntiin, Sami Mondolin mestariksi sivu 15 Matkalla tulevaisuuteen Tätä lukiessanne on uusi liittohallitus valittu. Tai tarkemmin: allekirjoittanut ja maajoukkueen johtaja/liigasihteeri ovat Risto Spora saaneet kyytiä tai työnsä jatkajiksi virkeät voimat. dellisessä lehdessä kirjoitin pienes- heti loppua. Jos meillä ei ole kykyä näyttää rantaa toimintaansa. Koska me emme toi- tä toiveestani siirtyä takavasemmal- olevamme osaajia, niin uudet harrastajat jää- mi emmekä voi toimia yritysmaailman ta- E le hallitustyöskentelystä ja tiesin jo vät haavistamme. paan osakkailta tai rahoituslaitoksilta lisära- silloin että Tapani Heikkilällä on samat Vaikka liitto on voittoa tavoittelematon hoitusta pyytäen, niin pienet raha- ja hen- ajatukset, mutta minun asiani ei ole niitä yhdistys, hienommin World Darts Federa- kilöresurssit, sisäinen ja ulkoinen vastarin- tuoda julki. Sittemmin Tapsa tarinoi netis- tionin tapaan amerikkalaisittain lausuttuna ta sekä suuri paine välttää ristiriitaisia vies- sä ja kertoi omat ajatuksensa. Samalla meni ns. nonprofit-organisaatio, kohtaamme me tejä, ovat meidän pulmiamme suunnittelun myös tämä pääkirjoitus uusiksi, sillä syys- toiminnassamme kovaa kilpailua ympäris- puutteen ohessa. Näiden pulmien avaajaa kuun tarinoissa oli pääpiirtein samat asiat tössämme. Siinä pärjätäksemme tarvitsem- ja ratkaisijaa kaipaamme. Ehkä hän istuu kuin valmiiksi kirjoitetussa jutussani tähän me osaamista usealta eri osa-alueelta ja toi- jo hallituksessa. sivulle 2. von, että Hämeenlinnan kokouksessa saim- Otan vielä myöhemmin paria asiaa kir- me hallitukseen nimenomaan osaajia eikä Liiga joitukseni raadosta esiin, mutta ensin halu- taaksepäin tuijottajia. Toivon, että saimme Hallitus käsitteli liiga-asiaa kesällä koko- aisin herättää kerhot miettimään liittomme viestikapulan kuljettajia, joilla kapula myös uksessaan Tampereella ja päätyi odottaval- todellista suuntaa. Liitolla ei ole tällä hetkel- pysyy kädessä. le kannalle, kuten moni on jo Tapsan Tari- lä aatteellista johtajaa. -

Darts Championship Online | Darts TV: All Darts Championship Stream Link 4

1 / 2 Live Darts TV: All Darts Championship Online | Darts TV: All Darts Championship Stream Link 4 Bet and browse odds for all sports with Sky Bet. Horse racing, Football, Accumulators and In Play.. Watch the best Tournament channels and streamers that are live on Twitch! Check out their featured videos for other Tournament clips and highlights.. 7 days ago — Catch all the best bits from Stream Two from Players Championship 18 Watch darts LIVE: video.pdc.tv News and Website ... 2 hours ago. 676 .... Darts youtube channels list ranked by popularity based on total channels subscribers, video ... from all the PDC's live events throughout the year, including the World Darts Championship and the Premier League Darts! ... The Netherlands About Youtuber The Dart channel where videos are posted by Kenzo Fernandes.. PDC, Premier League Darts, . ... Darts. All Games. All. LIVE Games. LIVE. Finished. Scheduled. 12/07 Mo. WORLDOnline Live League - Second stage ... Owen R. (Wal). 4. 3. Burness K. (Nir). Hogarth R. (Sco). 4. 1. Heneghan C. (Irl) ... Top darts events in the 2020/2021 season: PDC World Darts Championship 15.12.. Dec 30, 2020 — The World Darts Championship continues this week but how can fans ... Express Sport is on hand with all the TV coverage and live stream ... 0 Link copied ... The Scot was made to pay for a series of missed doubles in the first .... Registration for the TOTO Dutch Open Darts 2021 is open. This unique darts event will take place from Friday 3th until Sunday 5th of September in the Bonte ... Apr 17, 2020 — Fallon has signed up to an online tournament called MODUS Icons of Darts that has already been running for two weeks and streams live for ... -

The Eagle 2008

VOLUME 11 0 FOR MEMBERS OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE The Eagle 2008 150TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE ST JOHN’S COLLEGE U NI V E R S I T Y O F CA M B R I D GE The Eagle 2008 Volume 110 ST JOHN’S COLLEGE U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A MB R I D G E THE EAGLE Published in the United Kingdom in 2008 by St John’s College, Cambridge St John’s College Cambridge CB2 1TP www.joh.cam.ac.uk Telephone: 01223 338600 Fax: 01223 337720 Email: [email protected] First published in the United Kingdom in 1858 by St John’s College, Cambridge Designed and produced by Cameron Design: 01353 860006; www.cameronacademic.co.uk Printed by Cambridge Printing: 01223 358331; www.cambridgeprinting.org The Eagle is published annually by St John’s College, Cambridge, and is sent free of charge to members of St John’s College and other interested parties. Items to be considered for publication should be addressed to The Editor, The Eagle , Development Office, St John’s College, Cambridge, CB2 1TP, or sent by email to [email protected]. If you would like to submit Members’ News for publication in The Eagle , you can do so online at www.joh.cam.ac.uk/johnian/members_news. Page 2 www.joh.cam.ac.uk C O N T E N T S & E D I T O R I A CONTENTS & L EDITORIAL ST JOHN’S COLLEGE U N I V E R S I T Y O F C A MB R I D G E THE EAGLE Contents & Editorial C O N T E N T S & E D I T O R I A L Page 4 www.joh.cam.ac.uk Contents & Editorial THE EAGLE CONTENTS C O N T E N T S & E D I T Editorial .................................................................................................. -

Complete General Guide

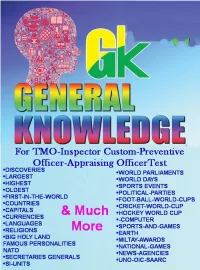

By : Faisal Qureshi LIST OF CONTENT DISCOVERIES LARGEST-HIGHEST-OLDEST-FIRST-IN-THE-WORLD WORLD-COUNTRIES-CAPITALS-CURRENCIES- LANGUAGES RELIGIONS GENERAL, MATH & ANALYTICS BIG HOLY LAND WORLD-FAMOUS-PERSONALITIES-PROFILES NORTH-ATLANTIC-TREATY-ORGANIZATION-OR-NATO LIST OF SECRETARIES GENERALS LIST-OF-SI-UNITS WORLD-FAMOUS-PARLIAMENTS WORLD-IMPORTANT-FAMOUS-DAYS FAMOUS-SPORTS-EVENTS-AND-INFORMATION FAMOUS-WORLD-POLITICAL-PARTIES FOOT-BALL-WORLD-CUPS CRICKET-WORLD-CUP HOCKEY WORLD CUP BASIC-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-COMPUTER GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-OF-SPORTS-AND-GAMES GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-EARTH WORLD-FAMO ANDES WORLD-HIGHEST-MILTAY-AWARDS NATIONAL-GAMES-OF-WORLD-COUNTRIES WORLD-FAMOUS-NEWS-AGENCIES FAMOUS-BOOKS-AND-THEIR-AUTHORS GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-UNO GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-OIC GENERAL-KNOWLEDGE-ABOUT-SAARC FAMOUS-RIVERS-OF-WORLD WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE RELIGIONS-OF-WORLD OLYMPIC-GAMES SAF-GAMES 1 By : Faisal Qureshi DISCOVERIES Galileo was first to discover rotation of earth • Kohler and Milstein discovered monoclonal antibodies. • Photography was invented by Mathew Barry • Albert Sabin invented Polio vaccine (oral) • Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleyev (Russian) published his first version of periodic table in 1869. • X-ray machine was invented by James Clark • Arthur Campton discovered x-rays and Cosmic rays. • Chadwick discovered Neutron • Telescope was invented by Galileo • Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming • Noble gases discovered by Cavendish • Gun powder was first invented in China • Velocity of light was measured by Michelson • Archimedes gave laws about Floatation of Bodies • Balloon fly up in air according to Archimedes‘s principle • Dr. Christian Bernard was first to perform heart transplant in 1967 in cape town(SA) • First man to receive artificial heart was Dr. -

Good-Darts.Pdf

GOOD DARTS! Copyright 1994 BY Gary R. Low, Ph.D. Darwin B. Nelson, Ph.D. The Good Darts book and "Dart Improvement Program" are protected by copyright law. No part of the book or program may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any other form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilm, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the authors. Without fail, dart players illegally copying parts of the program have become terminally cursed and have been observed throwing an inordinate number of l s and 5s at crucial points during match play. ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Darwin and Gary grew up together and have been close friends for forty years. As consulting psychologists, they have developed, researched, and authored positive assessment and life skills development programs that are used internationally in business, education, and clinical settings. In this book and program, they have applied their Personal Skills Development Model to improve their dart games and to put more fun in their lives. Their hope is that the Good Darts program will encourage you to do the same. INTRODUCTION The ability to throw Good Darts is a highly developed skill involving both technical and psychological skills. As authors and psychologists, we love darts more than any other game or sport. We have written this book and developed the "Dart Improvement Program" to improve our own skills, increase our own levels of personal satisfaction, and share our experiences with others. This book and program were designed for beginning and experienced players who desire to improve their dart game.