Early Medieval Rural Settlement in North Craven: a Reassessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCA 11 Great Scar Limestone Uplands

1 Rocky outcrops and scars near Winskill Stones above Ribblesdale above near Winskill Stones and scars Rocky outcrops LCA 11 Great Scar Limestone Uplands Yorkshire Dales National Park - Landscape Character Assessment YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS 2 LCA 11 Great Scar Limestone Uplands Numbered photographs illustrate specific key natural, cultural and perceptual features in the Great Scar Limestone Uplands LCA (see page 7) Key characteristics 1 • A series of areas following the exposed Great Scar Limestone across the southern part of the National Park, separated by the southern dales, containing areas of international and national biological/geological value. • Exposed limestone features including cliffs, screes, gorges, pavements and scattered boulders dominate the landscape, creating a rugged, worn character. These combine with shallow soil cover, shakeholes, potholes and caves to form classic karst landscape. • Panoramic views across the southern dales and southern dales fringes. In the western part of the area views are dominated by the Three Peaks landforms of Ingleborough, Whernside and Pen-y-ghent. Vertical limestone • Closely grazed, springy, flower-rich grasslands form a neat, bright green carpet between exposed rock features. cliffs at Kilnsey • Scattered trees or open, grazed woodland on scree slopes and cliffs, with occasional windblown trees or shrubs in Crag, Wharfedale ... cliffs and pavements at higher levels. Several large, semi-natural, undergrazed woodlands occur on the dale sides and a few, small, isolated plantations at higher elevations. • A general absence of streams and surface water features, with the exception of occasional small tarns and limited numbers of springs at the base of the limestone moors, mainly around Ingleborough. -

Grade 2 Listed Former Farmhouse, Stone Barns

GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an GRADE 2 LISTED FORMER FARMHOUSE, STONE BARNS AND PADDOCK WITHIN THE YORKSHIRE DALES NATIONAL PARK swale farmhouse, ellerton abbey, richmond, north yorkshire, dl11 6an Rare development opportunity in a soughtafter location. Situation Swale Farmhouse is well situated, lying within a soughtafter and accessible location occupying an elevated position within Swaledale. The property is approached from a private driveway to the south side of the B6260 Richmond to Reeth Road approximately 8 miles from Richmond, 3 miles from Reeth and 2 miles from Grinton. Description Swale Farmhouse is a Grade 2 listed traditional stone built farmhouse under a stone slate roof believed to date from the 18th Century with later 19th Century alterations. Formerly divided into two properties with outbuildings at both ends the property now offers considerable potential for conversion and renovation to provide a beautifully situated family home or possibly multiple dwellings (subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents). The house itself while needing full modernisation benefits from well-proportioned rooms. The house extends to just over 3,000 sq ft as shown on the floorplan with a total footprint of over 7,000 sq ft including the adjoining buildings. The property has the benefit of an adjoining grass paddock ideal for use as a pony paddock or for general enjoyment. There are lovely views from the property up and down Swaledale and opportunities such as this are extremely rare. General Information Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves The property is sold subject to, and with the benefit of all existing wayleaves, easements and rights of way, public and private whether specifically mentioned or not. -

Fawber Farmhouse, Horton-In-Ribblesdale

Hawes 01969 667744 Bentham 015242 63739 Leyburn 01969 622936 Settle 01729 825311 www.jrhopper.com 2 Church Street, Settle [email protected] North Yorkshire BD24 9JE “For Sales In The Dales” 01729 825311 Fawber Farmhouse, Horton-in-Ribblesdale Grade II Listed Farm House Remote Hill Side Location Sweeping Views Of The Dales Neighbouring Paddock Available & Bunk Barn Character Detached 3 Bed Renovation Required Bunk Barn Fantastic Opportunity To Renovate And Create A Large 4 Bed Farm House Work Shop Family/Holiday Home 2 Spacious Reception Rooms Wash Rooms & Store Room Viewing Is Essential After Large Dining Kitchen Discussion With Selling Agent Guide Price £200,000 - £250,000 RESIDENTIAL SALES • LETTINGS • COMMERCIAL • PROPERTY CONSULTANCY Valuations, Surveys, Mortgage Advice, Planning, Property & Antique Auctions, Removals, Inheritance Planning, Overseas Property, Commercial & Business Transfers, Acquisitions J. R. Hopper & Co. is a trading name for J. R. Hopper & Co. (Property Services) Ltd. Registered: England No. 3438347. Registered Office: Hall House, Woodhall, DL8 3LB. Directors: L. B. Carlisle, E. J. Carlisle Fawber Farmhouse, Horton-in-Ribblesdale DESCRIPTION Fawber Farmhouse and neighbouring bunk barn sit in the spectacular Yorkshire Dales National Parks with sweeping views of the Dales. Right in the heart of the 3 Peaks walking country, yet well connected with good roads to Hawes, Settle & Lancaster. Horton In Ribblesdale station gives commuting access to Leeds, Carlisle & beyond by train. Access by rough track requiring 4X4 vehicle or ¼ mile walk. Horton in Ribblesdale is a small village in Ribblesdale on the western side of Penyghent, the village has much to offer in the way of; pubs, a church, cafes, camp sites and a very reputable primary school. -

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Southern Yorkshire Dales Festive Self-Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Self-Guided Walking Destinations: Yorkshire Dales & England Trip code: MDPXA-7 1, 2, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy a festive break in the Yorkshire Dales with the walking experts; we have all the ingredients for your perfect self-guided escape. Newfield Hall, in beautiful Malhamdale, is geared to the needs of walkers and outdoor enthusiasts. Enjoy hearty local food, detailed route notes, and an inspirational location from which to explore this beautiful national park. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • The use of our Discovery Point to plan your walks – maps and route notes available www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Use our Discovery Point, stocked with maps and walks directions, for exploring the local area • Head out on any of our walks to discover the varied landscape of the Southern Yorkshire Dales on foot • Enjoy magnificent views from impressive summits • Admire green valleys and waterfalls on riverside strolls • Marvel at the wild landscape of unbroken heather moorland and limestone pavement • Explore quaint villages and experience the warm Yorkshire hospitality at its best • Choose a relaxed pace of discovery and get some fresh air in one of England's most beautiful walking areas • Explore the Yorkshire Dales by bike • Ride on the Settle to Carlisle railway • Visit the spa town of Harrogate TRIP SUITABILITY Explore at your own pace and choose the best walk for your pace and ability. -

Horton in Ribblesdale History Group Archive Catalogue (Box List)

Horton in Ribblesdale History Group Archive Catalogue (Box List) hhg001 Censuses hhg001_01. List of males in the parish dated 1803 hhg001_02. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1861 hhg001_03. Particulars of a sample of farms in Horton parish from: 1. 1823 Foster survey 2. 1851 census returns 3. 1867 directory hhg001_04. Farm list from 1823 Foster survey, 1851 census, 1881 census , and 1984 list hhg001_05. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1841 hhg001_06. Graph of population of Horton compared to England and Wales 1801 – 2001 hhg001_07. A field book and survey of the lower division of Horton in Ribblesdale hhg001_08. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1841 hhg001_09. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1851 – heads of household hhg001_10. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1851 hhg001_11. Transcript of 1867 directory for Horton in Ribblesdale hhg001_12. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1871 hhg001_13. Transcript of census return for Horton dated 1881 hhg002 Shows and Sales (auctions) hhg002_01. Horton and district young farmers’ club annual show programme dated 1960 hhg002_02. Catalogue of show entries dated 1950 hg002_03. List of subscriptions and donations not dated hhg002_04. Horton annual show dated 1967 hhg002_05. hhg002_06. Newspaper cutting, auction notification R Turner Bentham, cattle and sheep dated 1933 hhg002_07. Newspaper cutting, auction notification R Turner Bentham furnishings hhg002_08. Newspaper cutting, auction notification R Turner Bentham farmstock dated 1920 hhg002_09. Newspaper cutting, auction notification R Turner Bentham farmstock and furnishings undated hhg002_10. Newspaper cutting auction notification R Turner Bentham Newhouses farm, land and cottage dated 1935 hhg002)11. Newspaper cutting auction notification R Turner Bentham Fawber farm sale, cottage at Newhouses and land dated 1935 hhg002_12. -

Directory of Resources

SETTLE – CARLISLE RAILWAY DIRECTORY OF RESOURCES A listing of printed, audio-visual and other resources including museums, public exhibitions and heritage sites * * * Compiled by Nigel Mussett 2016 Petteril Bridge Junction CARLISLE SCOTBY River Eden CUMWHINTON COTEHILL Cotehill viaduct Dry Beck viaduct ARMATHWAITE Armathwaite viaduct Armathwaite tunnel Baron Wood tunnels 1 (south) & 2 (north) LAZONBY & KIRKOSWALD Lazonby tunnel Eden Lacy viaduct LITTLE SALKELD Little Salkeld viaduct + Cross Fell 2930 ft LANGWATHBY Waste Bank Culgaith tunnel CULGAITH Crowdundle viaduct NEWBIGGIN LONG MARTON Long Marton viaduct APPLEBY Ormside viaduct ORMSIDE Helm tunnel Griseburn viaduct Crosby Garrett viaduct CROSBY GARRETT Crosby Garrett tunnel Smardale viaduct KIRKBY STEPHEN Birkett tunnel Wild Boar Fell 2323 ft + Ais Gill viaduct Shotlock Hill tunnel Lunds viaduct Moorcock tunnel Dandry Mire viaduct Mossdale Head tunnel GARSDALE Appersett Gill viaduct Mossdale Gill viaduct HAWES Rise Hill tunnel DENT Arten Gill viaduct Blea Moor tunnel Dent Head viaduct Whernside 2415 ft + Ribblehead viaduct RIBBLEHEAD + Penyghent 2277 ft Ingleborough 2372 ft + HORTON IN RIBBLESDALE Little viaduct Ribble Bridge Sheriff Brow viaduct Taitlands tunnel Settle viaduct Marshfield viaduct SETTLE Settle Junction River Ribble © NJM 2016 Route map of the Settle—Carlisle Railway and the Hawes Branch GRADIENT PROFILE Gargrave to Carlisle After The Cumbrian Railways Association ’The Midland’s Settle & Carlisle Distance Diagrams’ 1992. CONTENTS Route map of the Settle-Carlisle Railway Gradient profile Introduction A. Primary Sources B. Books, pamphlets and leaflets C. Periodicals and articles D. Research Studies E. Maps F. Pictorial images: photographs, postcards, greetings cards, paintings and posters G. Audio-recordings: records, tapes and CDs H. Audio-visual recordings: films, videos and DVDs I. -

Find out More About the Three Peaks Project At

The Yorkshire Three Peaks walk Distance: 39km (24 miles) Parking: Horton car park ( BD24 0HF, SD 807 724) Other transport: Horton train station on the Settle to Carlisle line is close to the start Toilets: Horton car park Refreshments: pubs and café in Horton, Station Inn at Ribblehead and the Old Hill Inn in Chapel-le-dale This is a major challenge walk which is long and involves over 1600m (5000 feet) of climbing over the Three Peaks of Pen-y-ghent, Whernside and Ingleborough. There is one section on road, but the paths are good. You do need to be able to navigate and cope with conditions in the high fells. Route description 1. Walk south out of the village passing the Golden Lion pub and church and cross a small stream. Then turn left up a minor tarmac road. Follow this up towards Brackenbottom and just before reaching some buildings take a footpath on your left signed to Pen-y-ghent. 2. Climb steadily up through fields with Pen-y-ghent ahead of you. The final section of the route to the summit is steeper for a while before reaching the trig point and shelter. 3. Cross the wall at the summit and follow the clear path heading roughly north. This zig zags down, passing the gash of Hunt Pot, to reach the head of a walled lane. 4. Carry straight on to follow the new path over Whitber Hill to reach a clear track. Turn right and follow this for 1.5km (1 mile) and then take the path on the left towards Birkwith cave. -

Ingleton National Park Notes

IngletonNational Park Notes Don’t let rain stop play The British weather isn’t all sunshine! But that shouldn’t dampen your enjoyment as there is a wealth of fantastic shops, attractions and delicious food to discover in the Dales while keeping dry. Now’s the time to try Yorkshire curd tart washed down with a good cup of tea - make it your mission to seek out a real taste of the Dales. Venture underground into the show caves at Stump Cross, Ingleborough and White Scar, visit a pub and sup a Yorkshire pint, or learn new skills - there are workshops throughout the Star trail over Jervaulx Abbey (James Allinson) year at the Dales Countryside Museum. Starry, starry night to all abilities and with parking and other But you don’t have to stay indoors - mountain Its superb dark skies are one of the things that facilities, they are a good place to begin. biking is even better with some mud. And of make the Yorkshire Dales National Park so What can I see? course our wonderful waterfalls look at their special. With large areas completely free from very best after a proper downpour. local light pollution, it's a fantastic place to start On a clear night you could see as many as 2,000 your stargazing adventure. stars. In most places it is possible to see the Milky Way as well as the planets, meteors - and Where can I go? not forgetting the Moon. You might even catch Just about anywhere in the National Park is great the Northern Lights when activity and conditions for studying the night sky, but the more remote are right, as well as the International Space you are from light sources such as street lights, Station travelling at 17,000mph overhead. -

Offers in the Region of £275,000 Viewing Strictly by Appointment with the Vendor’S Sole Agents

15 HIGH STREET, LEYBURN 01969 600120 NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL8 5AQ EMAIL: [email protected] LOW WHITA FARM - LOT 2, LOW ROW RICHMOND, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL11 6NT A Grade II* Listed farmhouse with a range of attached • Barns for conversion barns and outbuildings with full planning permission with full planning granted for the creation of a five bedroom, three permission bathroom family home with three or four reception rooms. In addition, there is planning permission for the • Yorkshire Dales conversion of an Annexe within the grounds. The National Park property occupies a very large site extending to around • Grade II* Listed two acres including the original walled gardens to the south, which border a larger garden/paddock, together • Plot extending to around with a paddock to the north. two acres • Creation to a five The property has had full planning granted for the bedroom home with a creation of a 332m2 home with the auxiliary annexe one bedroom annexe building at 62m2 (Application number R/03/95A) Offers in the region of £275,000 VIEWING STRICTLY BY APPOINTMENT WITH THE VENDOR’S SOLE AGENTS WWW. GSCGRAYS. CO. UK LOW WHITA FARM - LOT 2, LOW ROW RICHMOND, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL11 6NT SITUATION AND AMENITIES The farmhouse is situated in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales National Park in Swaledale, on the southern side of the River Swale. The property is equi-distant between Healaugh and Low Row. The town of Reeth is situated approximately 5 miles away which is well served with a primary school, Doctors' survery, local shop, tea rooms, public houses and the Dales Bike Centre. -

Bunk Houses and Camping Barns

Finding a place to stay ……. Bunk Houses and Camping Barns To help you find your way around this unique part of the Yorkshire Dales, we have split the District into the following areas: Skipton & Airedale – taking in Carleton, Cononley, Cowling, Elslack, Embsay and Thornton-in-Craven Gargrave & Malhamdale – taking in Airton, Bell Busk, Calton, Hawkswick, Litton, and Malham Grassington & Wharfedale – taking in Bolton Abbey, Buckden Burnsall, Hetton, Kettlewell, Linton-in- Craven and Threshfield Settle & Ribblesdale – taking in Giggleswick, Hellifield, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Long Preston, Rathmell and Wigglesworth Ingleton & The Three Peaks – taking in Chapel-le-Dale and Clapham Bentham & The Forest of Bowland taking in Austwick Grassington & Wharfedale Property Contact/Address Capacity/Opening Grid Ref/ Special Info Times postcode Barden Barden Tower, 24 Bunk Barn Skipton, BD23 6AS Mid Jan – End Nov SD051572 Tel: 01132 561354 www.bardenbunkbarn.co.uk BD23 6AS Wharfedale Wharfedale Lodge Bunkbarn, 20 Groups Lodge Kilnsey,BD23 5TP All year SD972689 www.wharfedalelodge.co.uk BD23 5TP [email protected] Grange Mrs Falshaw, Hubberholme, 18 Farm Barn Skipton, BD23 5JE All year SD929780 Tel: 01756 760259 BD23 5JE Skirfare John and Helen Bradley, 25 Inspected. Bridge Skirfare Bridge Barn, Kilnsey, BD23 5PT. All year SD971689 Groups only Dales Barn Tel:01756 753764 BD23 5PT Fri &Sat www.skirefarebridgebarn.co.uk [email protected] Swarthghyll Oughtershaw, Nr Buckden, BD23 5JS 40 Farm Tel: 01756 760466 All year SD847824 -

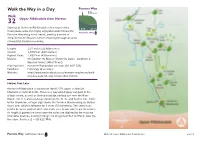

Walk the Way in a Day Walk 32 Upper Ribblesdale from Horton

Walk the Way in a Day Walk 32 Upper Ribblesdale from Horton Starting at Horton-in-Ribblesdale in the heart of the 1965 - 2015 three peaks area, this highly enjoyable walk follows the Pennine Way along stony tracks, passing a series of deep limestone fissures, before returning through an area of beautiful limestone scenery. Length: 13½ miles (22 kilometres) Ascent: 1,575 feet (480 metres) Highest Point: 1,437 feet (438 metres) Map(s): OS Explorer OL Map 2 (‘Yorkshire Dales - Southern & Western Areas’) (West Sheet) Starting Point: Horton-in-Ribblesdale car park (SD 808 726) Facilities: Full range of services. Website: http://www.nationaltrail.co.uk/pennine-way/route/walk- way-day-walk-32-upper-ribblesdale-horton Harber Scar Lane Horton-in-Ribblesdale is located on the B6479, about 5 miles (8 kilometres) north of Settle. There is a ‘pay and display’ car park in the village centre, as well as limited roadside parking just over the River Ribble. There is also a railway station on the Settle and Carlisle line. Close to the Crown Inn, a finger sign shows the Pennine Way heading up Harber Scar Lane, which is followed for 3 miles (5 kilometres). The stony track climbs between walls of white limestone as it heads north-east then north. As height is gained the views over the valley are blighted by the massive limestone quarries. Cutting through the dry gully of Sell Gill Beck, note the limestone fissures (1 = SD 812 744). Walk 32: Upper Ribblesdale from Horton page 1 Horton-in-Ribblesdale followed north along another stony track - an old pack-horse route, 2¼ Horton-in-Ribblesdale is the focal point of the three peaks area. -

Horton-In- Ribblesdale PEN-Y-GHENT Ribblehead

70 Deepdale 80 686 4. RIBBLEHEAD. 10.4 miles; 5:15 hrs N THREECrag HillPEAKS CHALLENGE Take road NW from Station Inn to ROUTE pass Bleaalongside Viaduct on path for 24 miles (38.6 km) WhernsideMoor . Cross railway line by Cumulative distances and guidance aqueduct and follow path steeply NW 3. HIGH BIRKWITH. 7.0 miles; 3:45 hrs times are shown at each stage. for Dent Dale. Cross fence stile on left Cross road & over small hill to drop to a gate. Timings and distances based on the Continue NW to cross God’s Bridge and on to Whitber Hill route and follow path to Whernside summit Oughtershaw 736 Nether Lodge. Follow farm access road out to WHERNSIDE B6479 and turn right on road to Ribblehead Beckermonds Cam BLACK DUBB MOSS ROUTE WHITBER HILL ROUTE 80 5. WHERNSIDE. 14.2 miles; 7:35 hrs Fell [Until 2013] Go straight on Gearstones [From 2013] Continue Continue S descending gently along ridge at sharp left bend, turning following PW down to the with wall on right, until path bears left NW to cross Hull Pot Beck gate at Horton Scar Lane. steeply downhill to Bruntscar. Follow access at stepping stones. Track Ribblehead Pass this & climb up over road south for The Hill Inn to Philpin Lane, becomes very boggy at P onto Low Sleights Rd. Left to Hill Inn ck e Whitber Hill, bearing left at e n Black Dubb Moss. Go on NW B n i wall corner and continue NW m n a e to cross PW at a stile.