Children's Literature Grows Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season's Readings: Naughty Or Nice?

R E S O U R C E S • S E R V I C E S • E V E N T S D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 7 Season’s Readings: Naughty or Nice? Looking for a meaningful gift for that someone special in your life? Having a hard time finding the perfect present for the person who has everything? The Library has the solution for you! Books make meaningful gifts that entertain long after the holiday season is over! Members of the East Baton Rouge Parish Library staff have compiled a great list of books, music CDs, and movies to make this holiday season one of the greatest yet. From tales of heart-warming, abiding love, to your favorite holiday recipes, the following selections are sure to please, whether you like them “Naughty or Nice”! Naughty List Nice List • Holidays on Ice by David Sedaris • Good People All: A Celtic Yuletide Tradition – CD by Magical Strings • Holiday Heart – DVD • Christmas in Connecticut – DVD • 12 Yats of Christmas – CD by Benny Grunch & Bunch • The Attic Christmas by B.G. Hennessy • Elf – DVD • A Dozen Silk Diapers by Melissa Kajpust • Hogfather by Terry Pratchett • The Wool Cap – DVD • National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation – DVD • Christmas Letters by Debbie Macomber • Bad Santa – DVD • The Littlest Angel by Charles Tazewell • Santa Baby – CD by Eartha Kitt • Miracle and Other Christmas Stories by Connie Willis • Love Actually – DVD • A Christmas in Wales • The Stupidest Angel, a by Dylan Thomas Heartwarming Tale of Christmas Terror by Christopher Moore • The Homecoming – DVD • How the Grinch Stole Christmas • Betty Crocker Christmas Cookbook by -

Stephen Colbert's Super PAC and the Growing Role of Comedy in Our

STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE BY MELISSA CHANG, SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS ADVISER: CHRIS EDELSON, PROFESSOR IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS UNIVERSITY HONORS IN CLEG SPRING 2012 Dedicated to Professor Chris Edelson for his generous support and encouragement, and to Professor Lauren Feldman who inspired my capstone with her course on “Entertainment, Comedy, and Politics”. Thank you so, so much! 2 | C h a n g STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE Abstract: Comedy plays an increasingly legitimate role in the American political discourse as figures such as Stephen Colbert effectively use humor and satire to scrutinize politics and current events, and encourage the public to think more critically about how our government and leaders rule. In his response to the Supreme Court case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) and the rise of Super PACs, Stephen Colbert has taken the lead in critiquing changes in campaign finance. This study analyzes segments from The Colbert Report and the Colbert Super PAC, identifying his message and tactics. This paper aims to demonstrate how Colbert pushes political satire to new heights by engaging in real life campaigns, thereby offering a legitimate voice in today’s political discourse. INTRODUCTION While political satire is not new, few have mastered this art like Stephen Colbert, whose originality and influence have catapulted him to the status of a pop culture icon. Never breaking character from his zany, blustering persona, Colbert has transformed the way Americans view politics by using comedy to draw attention to important issues of the day, critiquing and unpacking these issues in a digestible way for a wide audience. -

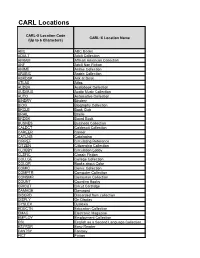

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Stories in Support of Education

en doors Open books - Op 20-26 April 2009 Nelson Mandela F Queen Rania Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie F Paulo Coelho Ishmael Beah F Devli Kumari Dakota Blue Richards F Michael Morpurgo Rowan Williams F Beverley Naidoo Desmond Tutu F Alice Walker Natalie Portman F Angélique Kidjo Mary Robinson Stories in support of education This storybook was created by the Global Campaign for Education. A compilation of short stories from influential figures around the world, The Big Read tells remarkable tales of education and the struggles of those who are denied the chance to learn. By reading this book and then writing your name at the end, you can help everyone have the chance of an education. www.campaignforeducation.org/bigread How you can be part of the Big Read: 1. Read or listen to a story from this book 2. Write your name on the last page 3. Send the message on the last page to your government 4. Let us know you have taken part (either online or using the back of this book) You are taking part in the Big Read with people from all over the world. This book is being distributed in more than 100 countries. This same book can be read online or downloaded from our website. Sign up here to receive updates on the Big Read around the world: www.campaignforeducation.org/bigread The Big Read events are happening throughout the Global Campaign for Education’s Action Week, 20th - 26th April 2009. All your names will be added to this book and delivered to world leaders and the United Nations. -

Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: the Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 14 Issue 1—Spring 2018 Toward a Theory of the Dark Fantastic: The Role of Racial Difference in Young Adult Speculative Fiction and Media Ebony Elizabeth Thomas Abstract: Humans read and listen to stories not only to be informed but also as a way to enter worlds that are not like our own. Stories provide mirrors, windows, and doors into other existences, both real and imagined. A sense of the infinite possibilities inherent in fairy tales, fantasy, science fiction, comics, and graphic novels draws children, teens, and adults from all backgrounds to speculative fiction – also known as the fantastic. However, when people of color seek passageways into &the fantastic, we often discover that the doors are barred. Even the very act of dreaming of worlds-that-never-were can be challenging when the known world does not provide many liberatory spaces. The dark fantastic cycle posits that the presence of Black characters in mainstream speculative fiction creates a dilemma. The way that this dilemma is most often resolved is by enacting violence against the character, who then haunts the narrative. This is what readers of the fantastic expect, for it mirrors the spectacle of symbolic violence against the Dark Other in our own world. Moving through spectacle, hesitation, violence, and haunting, the dark fantastic cycle is only interrupted through emancipation – transforming objectified Dark Others into agentive Dark Ones. Yet the success of new narratives fromBlack Panther in the Marvel Cinematic universe, the recent Hugo Awards won by N.K. Jemisin and Nnedi Okorafor, and the blossoming of Afrofuturistic and Black fantastic tales prove that all people need new mythologies – new “stories about stories.” In addition to amplifying diverse fantasy, liberating the rest of the fantastic from its fear and loathing of darkness and Dark Others is essential. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Bill Fawcett______24951 Middle Fork Road Barrington, Illinois 60010 U.S.A

Bill Fawcett___________________________________________________ 24951 Middle Fork Road Barrington, Illinois 60010 U.S.A. 8472779686 [email protected] Bill has been a professor, teacher, corporate executive, and college dean. His entire life has been spent in the creative fields and managing other creative individuals. He is one of the founders of Mayfair Games, a board and role play gaming company. As an author Bill has written or coauthored over a dozen books and dozens of articles and short stories. As a book packager, a person who prepares series of books from concept to production for major publishers, his company Bill Fawcett & Associates has packaged over 250 titles for virtually every major publisher. He founded, and later sold, what is now the largest hobby shop in Northern Illinois. Bill’s first commercial writing appeared as articles in the Dragon Magazine and include some of the earliest appearances of classes and monster types for dungeons and Dragons. With Mayfair Games created, wrote, and edited many of the over 50 “Role Aides” Role Playing Game modules and supplements released by Mayfair in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period he also designed almost a dozen board games, including several Charles Roberts Award (Gaming's Emmy) winners such as Empire Builder and Sanctuary. Bill Fawcett continues to develop new internet projects. His novl writing began with the juvenile series, Swordquest for Ace Penguin Putnam Publishing. He wrote or cowrote four fantasy novels, beginning with the Lord of Cragsclaw. The Fleet series he created with David Drake has become a classic of military science fiction. -

Discovering by Analysis: Harry Potter and Youth Fantasy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 865 IR 058 417 AUTHOR Center, Emily R. TITLE Discovering by Analysis: Harry Potter and Youth Fantasy. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 38p.; Master of Library and Information Science Research Paper, Kent State University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Childrens Literature; *Fantasy; Fiction; Literary Criticism; *Reading Material Selection; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Harry Potter; *Reading Lists ABSTRACT There has been a recent surge in the popularity of youth fantasy books; this can be partially attributed to the popularity of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. Librarians and others who recommend books to youth are having a difficult time suggesting other fantasy books to those who have read the Harry Potter series and want to read other similar fantasy books, because they are not as familiar with the youth fantasy genre as with other genres. This study analyzed a list of youth fantasy books and compared them to the books in the Harry Potter series, through a breakdown of their fantasy elements (i.e., fantasy subgenres, main characters, secondary characters, plot elements, and miscellaneous elements) .Books chosen for the study were selected from lists of youth fantasy books recommended to fantasy readers and others that are currently in print. The study provides a resource for fantasy readers by quantifying the elements of the youth fantasy books, as well as creating a guide for those interested in the Harry Potter books. It also helps fill a gap in the research of youth fantasy. Appendices include a youth fantasy reading list, the coding sheet, data tables, and final annotated book list.(Contains 10 references and 9 tables.)(Author/MES) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Mini-Episode 14: High Fantasy

Not Your Mother’s Library Transcript Mini-Episode 14: High Fantasy (Brief intro music) Rachel: Hello, and welcome to Not Your Mother’s Library, a readers’ advisory podcast from the Oak Creek Public Library. I’m Rachel, and you might be familiar with my voice by now because both Leah and I have been recording a whole bunch of mini-episodes while the library is closed due to the Coronavirus pandemic. Ya know, I played that board game once. “Pandemic,” I mean. I thought it was too complex, but that’s coming from someone who periodically forgets the rules of “Yahtzee.” Anyway, yes, at time of recording Oak Creek Public Library is closed, and staff like myself are offering virtual services in lieu of in- person interactions. Practice social distancing with us, and stay safe out there, everyone. Or, preferably, stay safe in there. Like, indoors. At home. You can catch up on being a couch potato by listening to podcasts, or take us with you while you go for a jog around the neighborhood. New media is versatile like that, and exercise is important. Technically. But, back on track. Leah and I are sharing some of our favorite books, movies, and other schtuff [sic]. Since this episode and the few that follow will be going out in May 2020, I thought I’d go with a new format just for the month. Let’s look into specific genres. This episode, as you can see from the title, we’ll explore high fantasy, and I plan to touch on other genres like horror and comedy and…niche…in future eps. -

Core Collections in Genre Studies Romance Fiction

the alert collector Neal Wyatt, Editor Building genre collections is a central concern of public li- brary collection development efforts. Even for college and Core Collections university libraries, where it is not a major focus, a solid core collection makes a welcome addition for students needing a break from their course load and supports a range of aca- in Genre Studies demic interests. Given the widespread popularity of genre books, understanding the basics of a given genre is a great skill for all types of librarians to have. Romance Fiction 101 It was, therefore, an important and groundbreaking event when the RUSA Collection Development and Evaluation Section (CODES) voted to create a new juried list highlight- ing the best in genre literature. The Reading List, as the new list will be called, honors the single best title in eight genre categories: romance, mystery, science fiction, fantasy, horror, historical fiction, women’s fiction, and the adrenaline genre group consisting of thriller, suspense, and adventure. To celebrate this new list and explore the wealth of genre literature, The Alert Collector will launch an ongoing, occa- Neal Wyatt and Georgine sional series of genre-themed articles. This column explores olson, kristin Ramsdell, Joyce the romance genre in all its many incarnations. Saricks, and Lynne Welch, Five librarians gathered together to write this column Guest Columnists and share their knowledge and love of the genre. Each was asked to write an introduction to a subgenre and to select five books that highlight the features of that subgenre. The result Correspondence concerning the is an enlightening, entertaining guide to building a core col- column should be addressed to Neal lection in the genre area that accounts for almost half of all Wyatt, Collection Management paperbacks sold each year.1 Manager, Chesterfield County Public Georgine Olson, who wrote the historical romance sec- Library, 9501 Lori Rd., Chesterfield, VA tion, has been reading historical romance even longer than 23832; [email protected].