1. a Crisis of Quality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

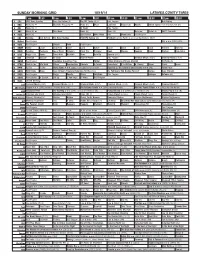

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Canada and the Middle East Today: Electoral Politics and Foreign Policy

CANADA AND THE MIDDLE EAST TODAY: ELECTORAL POLITICS AND FOREIGN POLICY Donald Barry Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper came to power in 2006 with little experience in foreign affairs but with a well developed plan to transform his minority Conservative administration into a majority government replacing the Liberals as Canada’s “natural governing party.”1 Because his party’s core of Anglo-Protestant supporters was not large enough to achieve this goal, Harper appealed to non- traditional Conservatives, including Jews, on the basis of shared social values. His efforts were matched by those of Jewish leaders and the government of Israel to win the backing of the government and its followers in the face of declining domestic support for Israel and the rise of militant Islamic fundamentalism. These factors accelerated a change in Canada’s Middle East policy that began under Prime Minister Paul Martin, from a carefully balanced stance to one that overwhelm- ingly favors Israel. Harper’s “pro-Israel politics,” Michelle Collins observes, has “won the respect—and support—of a large segment of Canada’s organized Jewish community.”2 However, it has isolated Canada from significant shifts in Middle East diplomacy and marginalized its ability to play a constructive role in the region. Harper and the Jewish Vote When he became leader of the Canadian Alliance party, which merged with the Progressive Conservatives to form the Conservative Party of Canada in 2004, Tom Flanagan says that Harper realized “The traditional Conservative base of Anglophone Protestants [was] too narrow to win modern Canadian elections.”3 In a speech to the conservative organization Civitas, in 2003, Harper argued that the only way to achieve power was to focus not on the tired wish list of economic conservatives or “neo-cons,” as they’d become known, but on what he called “theo-cons”—those social conservatives who care passionately about hot-button issues that turn on family, crime, and defense. -

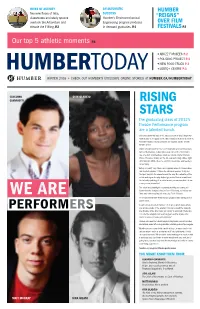

Humber Today in a Past Interview

HIVES OF ACTIVITY AN AUTOMATIC HUMBER Two new floors of labs, SUCCESS classrooms and study spaces Humber’s Electromechanical “REIGNS” overlook the Arboretum and Engineering program produces OVER FILM elevate the F Wing. P. 2 in-demand graduates. P. 4 FESTIVALS P. 3 Our top 5 athletic moments P. 4 + ABUZZ FOR BEES P.2 + POLICING PROJECT P.3 + NEW FOOD TRUCK P.3 + LGBTQ+ CENTRE P.3 WINTER 2016 • CHECK OUT HUMBER’S EXCLUSIVE ONLINE STORIES AT HUMBER.CA/HUMBERTODAY GIACOMO OYIN OLADEJO GIANNIOTTI RISING STARS The graduating class of 2012’s Theatre Performance program are a talented bunch. Giacomo Gianniotti was in the latest season of Grey’s Anatomy. Matt Murray is a regular on the ABC Family show Kevin from Work. And Oyin Oladejo and Sina Gilani are regulars on the Toronto theatre scene. Gilani is best known for his recent dramatic (and controversial) turn in the Buddies in Bad Times play The 20th of November. The one-man show features Gilani as school shooter Bastian Bosse. It’s based mainly on the 18-year-old’s blog entries, right until Nov. 20, 2006, when he shot 30 classmates and teachers in Germany. “Acting is a craft,” says Gilani, who originally came to Canada from Iran to study physics. “It takes the rehearsal process to try and find your way into the character and the play. The collective of the artists working on the play helped get inside Bastian's world and his twisted psychology. It is called a one-person show, but it is not a one-person production.” The actor and playwright is currently working on touring his Summerworks-featured play In Case of Nothing, as well as two films and workshopping his new play Field of Reeds. -

Production List Aug 20, 2010

Aug 20, 2010 (This List is updated approximately every two weeks) Phone Project Title Company Producer(s) Director(s) PM / Co-ordinator LM(s) / ALM(s) Key Cast Fax Shooting Dates E-mail Features Sundays At Tiffany's Dan Wigutow Judith P: 647 837 3318 Idaho Productions Limited Mark Piznarski Chris Danton Keith Large TBD Sept. 7 -Oct. 3/10 Verno Golov F: 647-837-3317 Thank You UTV Software Comm.Ltd. Raj Shah/Alan McAlex Anees Bazmi Amit Mehta/Bina Shah Brad Alexander Akshay Kumar P: 647-381-5553 July 25 - Sept 17/10 ReelEye J.A.R. Ent. Michael Campbell Sonam Kapoor Irian Kahn Take This Waltz Joe's Daughter Inc. Susan Cavan Sarah Polley D.J. Carson (LP) Fred Kamping Michelle Williams P: 647 837-3315 July 12 - Sept 1/10 Joanne Jackson (PM) Mark McFadden Luke Kirby F: 647 837-3316 Adnrea Nesbitt (PC) Seth Rogen TV Movies / MOWs Series Being Erica 03 Being Erica III Prods. Inc. Reggie Robb Various Gina Fowler Mark Logan (LM) Erin Karpluk P: 416 915-1785 May 17 - Oct 15/10 Drazen Baric (ALM) Michael Riley F: 416 915-1783 Warner Strauss(LM) Fernando Da Silva (ALM) Best Laid Plans BLP Productions (Ontario) Steve Solomos John Kent Harrison Bill Marks Richard Hughes TBA P: 416-253-4681 Aug.30/2010-Sept.26/2010 Inc. Alexandra MacKenzie Trevor Weber F: 416-253-4018 Degrassi: TNG 10 Mar Epitome Pictures Inc. Linda Schuyler Various Michael Bawcutt Chris Martin TBA P: 416 752-7627 29 - Nov 4/10 Stephen Stohn Linda Keyworth F: 416 752-8083 Dual Suspects Cineflix ( Dual Suspects) Inc. -

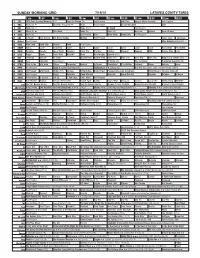

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn. -

Number of Home Schools Growing Across the State

•Football, girls volleyball, cheerleading, boys soccer, cross-country and girls tennis tryouts and practice underway among four area high schools. •When the World Series came toWhiteville. Sports See page 1-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, August 3, 2015 Number of home schools Whiteville Volume 125, Number 10 City Hall Whiteville, North Carolina growing across the state 75 Cents More than 340 in Columbus County moving due By NICOLE CARTRETTE to mold Inside News Editor By JEFFERSON WEAVER When the Michaud sisters of Staff Writer 3-A Whiteville head back to school •Railroad deal this week there will be no uniform Whiteville’s city offices will likely have a ‘slightly delayed’ to put on, book bag to pack or new temporary home within a few months, nervousness about meeting a new according to officials. 4-A teacher. “The mold problem has just become too Isabella, 12, and Collette, 9, are bad,” said City Manager Darren Currie. •Overpass bridge among an estimated 521 children in “Right now we’re setting up a workshop with damaged; fire at Lake 341 homeschools across Columbus council to explore all our options.” destroys motorcycles. County. The entire building will require mold re- Their mother, Laura Michaud, mediation, Currie said. has been homeschooling her The city has been involved in a drawn-out daughters for the last six years. fight against mold that started in the base- “It was just a decision that we ment of the 1930s structure. The mold spread felt was a good fit for our family,” through the ventilation system, and affects said Michaud, who is a member of nearly every part of the building. -

Wedding Band Bio Poster.Indd

PLAY BY THE BOOK: UPRISING SERIES Wedding Band by Alice Childress MARION ADLER HERMANN’S MOTHER ALLISON EDWARDSCREWE MATTIE Stratford: Grandma Elliot in Billy Elliot the Musical, lyricist for The Merry Wives of Allison has traveled across Canada performing on stage and screen. Selected Windsor, Lady Markby in An Ideal Husband, Mrs. Dubose in To Kill a Mockingbird, credits: Theatre: Serving Elizabeth (Western Canada Theatre); The Color Purple Cicero, Volumnius in Julius Caesar, Lady Capulet in Romeo and Juliet, Gabrielle (Citadel Theatre and Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre); School Girls; Or, the African in The Madwoman of Chaillot, Diana in and lyricist for The Adventures of Pericles. Mean Girls Play (Obsidian and Nightwood Theatre); How Black Mothers Say Elsewhere: Paulina and Hermione in The Winter’s Tale, Queen Marguerite in I Love You (Factory Theatre); All Shook Up (The Globe Theatre); Miss Bennet: Exit the King, Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, Philaminte in The Learned Christmas at Pemberley (Citadel); Girls Like That (Tarragon Theatre); ’da Kink in Ladies, Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Shakespeare Theatre of New My Hair (Theatre Calgary, National Arts Centre); Dreamgirls (Grand Theatre). Film/ Jersey); Princess of France in Love’s Labour’s Lost, Emilia in Othello, Mistress TV: The Handmaid’s Tale (MGM/Hulu), Baby in a Manger (BrainPower), Surviving Quickly in Henry IV Part 2 (Shakespeare Santa Cruz). Et cetera: Ms Adler is an Evil (Cinefl ix), Black Actress (JungleWild). Audio Dramas: Liming (Expect Theatre/CBC), Every Second internationally acclaimed, award-winning lyricist. of Every Day (Factory Theatre). Training: High Honours Bachelor of Music Theatre, Sheridan College. -

Coca-Cola Stage Backgrounder 2016

May 26, 2016 BACKGROUNDER 2016 Coca-Cola Stage lineup Christian Hudson Appearing Thursday, July 7, 7 p.m. Website: http://www.christianhudsonmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristianHudsonMusic Twitter: www.twitter.com/CHsongs While most may know Christian Hudson by his unique and memorable performances at numerous venues across Western Canada, others seem to know him by his philanthropy. This talented young man won the prestigious Calgary Stampede Talent Show last summer but what was surprising to many was he took his prize money of $10,000 and donated it all to the local drop-in centre. He was touched by the stories he was told by a few people experiencing homelessness he had met one night prior to the contest’s finale. His infectious originals have caught the ears of many in the industry that are now assisting his career. He was honoured to receive 'The Spirit of Calgary' Award at the inaugural Vigor Awards for his generosity. Hudson will soon be touring Canada upon the release of his first single on national radio. JJ Shiplett Appearing Thursday, July 7, 8 p.m. Website: http://www.jjshiplettmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jjshiplettmusic/ Twitter: www.twitter.com/jjshiplettmusic Rugged, raspy and reserved, JJ Shiplett is a true artist in every sense of the word. Unapologetically himself, the Alberta born singer-songwriter and performer is both bold in range and musical creativity and has a passion and reverence for the art of music and performance that has captured the attention of music fans across the country. He spent the major part of early 2016 as one of the opening acts on the Johnny Reid tour and is also signed to Johnny Reid’s company. -

Sunday Morning Grid 7/19/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/19/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Gospel Music Presents Paid Program 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Beach Volleyball Golf 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Open Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Miss Nobody (2010) (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Rudy ››› (1993) (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Zoom › (2006) Tim Allen. (PG) Chimpanzee ›› (2012) (G) Ben Hur Un príncipe judío enfrenta traición. -

Eulogy for William Krehm 2 SNC-Lavalin and the Rule of Law Canada’S SNC-Lavalin Affair: by Jonathan Krehm Capital

THE JOURNAL OF THE COMMITTEE ON MONETARY AND ECONOMIC REFORM $3.95 Vol. 31, No. 1 • JANUARY–FEBRUARY 2019 CONTENTS Eulogy for William Krehm 2 SNC-Lavalin and the Rule of Law Canada’s SNC-Lavalin Affair: By Jonathan Krehm Capital. Unfortunately, as a teenager with The Site C Dam Project and My father passed away peacefully at my head on fire – these were the opening Bulk Water Export home on Friday, April 19, at 11 pm, in his years of the Depression – I could not avoid Canada’s Corrupt Foreign Policy 106th year. He had an amazing full life. We polemicizing against Winston Churchill on Come Home to Roost were blessed that he enjoyed relatively good my exam paper on history. Obviously this The Real SNC-Lavalin Issues health until the end. and the diverted time His generation is did not help my chanc- Why Wilson-Raybould Was Right now gone. His pass- es for a scholarship, Sordid SNC-Lavalin Affair ing marks the end of which in fact I didn’t Exposes Canada as a Plutocracy, an era. Not just for us get. So I spent two Not a Democracy here gathered, but also years in a mathemat- Neoliberal Fascism and the Echoes for those who remem- ics and physics courses of History, Part II ber the struggles of the without money to buy A General Comment about the past. He was the last books. It did nothing Inquiry living North American for my chances of be- A Comment about Paradigm Shift who went to Spain to coming a physicist or 19 BC Leads the Way to a Better support the Spanish Re- a mathematician. -

Canada's #1 Original Drama Rookie Blue Moves To

CANADA’S #1 ORIGINAL DRAMA ROOKIE BLUE MOVES TO WEDNESDAY NIGHTS STARTING JUNE 24 Global’s Ratings Juggernaut Blazes Through Competition with Over 1.5 Million Weekly Viewers For additional photography and press kit materials visit: http://shawmediatv.ca and follow us on Twitter at @GlobalTV_PR / @ShawMediaTV_PR For Immediate Release: TORONTO, June 22, 2015 – Starting June 24, Global’s homegrown hit Rookie Blue moves to an all new timeslot on Wednesday nights at 9pm ET/PT. The nation’s top Canadian drama of 2015 (A18-49, A25-54) had an explosive premiere this spring, and is averaging over 1.5 million weekly viewers (2+) with no intention of slowing down. This Wednesday’s all-new episode starts with a bang after a community-outreach baseball game erupts in a drive-by shooting and Gail’s relationship with her brother, Steve Peck, is put to the test in the search for the shooter. Meanwhile, Sam plans a getaway with Andy up to Oliver’s cabin, which goes off the rails in every possible way – except one. The sixth season of Rookie Blue has been chock-full of dramatic, edge-of-your-seat moments anchoring the series as Global’s #1 Canadian series of 2015. For additional data highlights, please see below. DATA HIGHLIGHTS Rookie Blue averages over 1.5 million weekly viewers (2+) Rookie Blue is Global’s #1 Canadian series of 2015 (+2, W25-54) Rookie Blue is the #1 Canadian drama series of 2015 (A18-49, A25-54) Rookie Blue is the #1 Canadian drama series of 2015 across all conventional in four meter markets (Toronto, Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver) (A18-49, A25-54) Viewers can also catch up on episodes from this season of Rookie Blue on Global Go.