Report: Rules, Rates, and Practices Relating to Detention, Demurrage, and Free Time for Containerized Imports and Exports Moving Through Selected United States Ports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effective 01/01/2000

FORM 6 Equipment Providers Party to the September 27, 2021 Uniform Intermodal Interchange and Facilities Access Agreement (UIIA) All insurance information should be provided directly to the UIIA office and not to the Equipment Providers listed below. Alpha Code Name and Address of Equipment Provider ACLU ACL/Grimaldi Group/Inarme, 50 Cardinal Drive, Westfield, NJ 07090 (Equipment Group) Tel: (908)518-7352; e-mail: [email protected] ANLC ANL Singapore Pte. Ltd. (formerly: US Lines LLC), 5701 Lake Wright Drive, Norfolk, VA 23502 (Equipment Operations) Tel: (562)624-5676 Fax: (703)341-1385, Dispute contact: [email protected] LAX/Long Beach: lax- [email protected]; West Coast: [email protected]; East Coast: [email protected] cgm.com; Midwest & Gulf [email protected]; All Regions for Reefer/OpenTop/Flatrack: [email protected]; All Regions for Chassis only: [email protected] APLU APL Co. Pte Ltd, 5701 Lake Wright Drive, Norfolk, VA 23502 (Equipment Operations) Tel: (562)624-5676 Fax: (703)341- 1385, Dispute contact: [email protected]; LAX/Long Beach: [email protected]; West Coast: [email protected]; East Coast: [email protected]; Midwest & Gulf [email protected]; All Regions for Reefer/OpenTop/Flatrack: [email protected]; All Regions for Chassis only: [email protected] BANR BAL Container Line Co., Ltd., One St. Louis Centre, Suite 5000, Mobile, AL 36602 (Mike Ausmus) Tel: (251)219-3310; Fax: (251)433-1461; e-mail: [email protected] BCLU Bermuda Container Line, Limited, One Gateway Center, Ste. -

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

U.S. Customs and Border Protection Report Update to Congress on Integrated Scanning System Pilot (Security and Accountability for Every Port Act of 2006, Section 232(c)) TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Legislative Requirement/Citation 5 Executive Summary 10 Background 11 Discussion 30 Conclusion 31 Acronyms REPORT UPDATE TO CONGRESS ON INTEGRATED SCANNING SYSTEM FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Legislative Requirement/Citation This report is the first in a series of semi-annual updates required by Section 232(c) of the Security and Accountability for Every Port Act of 2006 (SAFE Port Act), Pub L. No. 109-347, 120 Stat. 1917 (October 13, 2006). In Section 231 of the SAFE Port Act, Congress directed the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), in coordination with the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), as necessary, and the private sector and host governments when possible, to pilot an integrated scanning system at three foreign ports. Section 232 of the SAFE Port Act, reads: SEC. 232. SCREENING AND SCANNING OF CARGO CONTAINERS. (a) ONE HUNDRED PERCENT SCREENING OF CARGO CONTAINERS AND 100 PERCENT SCANNING OF HIGH-RISK CONTAINERS.— (1) SCREENING OF CARGO CONTAINERS — The Secretary shall ensure that 100 percent of the cargo containers originating outside the United States and unloaded at a United States seaport undergo a screening to identify high-risk containers. (2) SCANNING OF HIGH-RISK CONTAINERS —The Secretary shall ensure that 100 percent of the containers that have been identified as high-risk under paragraph (1), or through other means, are scanned or searched before such containers leave a United States seaport facility. -

Frequently Overlooked Risk Management Issues in Contracts of Affreightment and Sale Contracts

Frequently overlooked risk management issues in contracts of affreightment and sale contracts 2021 AMPLA Queensland Conference Chris Keane MinterEllison 18 June 2021 The focus of today’s presentation - risk associated with two contracts used to facilitate the export of Australian commodities: . the sale contract / offtake agreement / supply agreement (sale contract) . the contract of affreightment / voyage charterparty / bill of lading (sea carriage contract) Specific focus is on risk and risk mitigation options that are frequently overlooked (both at the time of contract formation and also when disputes arise) 2 Risk arising out of seemingly straightforward issues . Duration of the sale contract - overarching issue that impacts on many other considerations; legal and commercial considerations will overlap . Port(s) of loading and port(s) of discharge - relevant considerations include: access to certain berths; special arrangements regarding loading and unloading; port congestion and other factors likely to cause delay; and the desirability of not requiring a CIF buyer to nominate a specific port of unloading (e.g. “one safe port and one safe berth at any main port(s) in China…”) . Selection of vessel - risk will depend on which party to the sale contract is responsible for arranging the vessel; CIF sellers need to guard against the risk of selecting an unsuitable vessel; FOB sellers need to ensure they have a right to reject an unsuitable vessel nominated by the buyer 3 Risk arising out of seemingly straightforward issues . Selection of contractual carrier - needs to be considered as an issue separate from the selection of the vessel; what do you know (and not know) about the carrier?; note the difficulties the contractual carrier caused for both the seller and buyer in relation to the ‘Maryam’ at Port Kembla earlier this year; proper due diligence is critical; consider (among other things) compliance with anti-slavery, anti-bribery and sanctions laws and issues concerning care of seafarers, safety and environment . -

Ensenada International Terminal

World Ports HPH HPH Ports around the World 48 Ports in 25 Countries HPH Mexico EIT Hinterland Nuestros clientes EIT – Length of vessels 5,000 TEU 280 - 300 m 13 6,000 – 8,000TEU 17 300 – 330 m EIT: Biggest vessel calling Ensenada 9300 TEU 10,000 - 13,000 TEU 330 - 360 m 21 18,000 TEU 23 400 m EIT Capacity EIT: 280,000 Teus Dinamyc -Usage Today 60% -/ + 7,500 Teus Statics Vessel’s dailiy unloading capacity: 3,500 TEU (Usage today 30%) Delivery/Reception of containers per day (Customs hours): 400 Containers Services Contenerized cargo: Loading-unloading Delivery-reception Storage Electricity supply (refrigerated containers) Vanning / Devanning Labeling, stacking on pallets and general packing General Cargo: Grain loading to ship through pneumatic system Delivery-reception Storage Others Shipping Agency Logistics Coordination Chassis rental EIT TRANSPORT COORDINATION Inland Service provided in full or single container truck in order Servicie to provide an efficient service for our clients. Container Monitoring In real time cargo monitoring for a best control and of our customers cargo Cargo Insurance For container under EIT transportation there is no “late arrival cost”. Late Arrival Storage and custody of containers, empty or full in the EIT’s Container yard in Tijuana. Storage In Bond Transportation • Included in Mexican Customs Law • 3 border crossing points: Tijuana, Tecate and Mexicali • USA-Ensenada or Ensenada-USA Tracking container by EIT’s webpage The Consignee can track containers by: • Container number • Bill Landing B/L • Customs form number Consignees can review, the status of container by internet: www.enseit.com Container tracking system The system shows the container information as: status (in/out), dates and hours, vessel. -

FMC Will Continue to Allow Carriers 30 Days to File New Service

Signals: FMC and ocean freight industry news and developments View this email in your browser Volume 24, Number 11 November 3, 2020 Oakland, California SIGNALS™ provides detailed information on the regulations and activities of the US Federal Maritime Commission (FMC), and related developments in the ocean freight industry. For past issues, please consult our index. Signals™ Headlines - November 3, 2020 • FMC Will Continue to Allow Carriers 30 Days to File New Service Contracts • FMC Requests Comments on the Term “Merchant” in Carrier Bills of Lading • Proposal to Change FMC Regulation of Cruise Lines Issued • Transpacific Eastbound Carriers File GRIs Effective November 15 and December 1, 2020 • Caribbean Shipowners Association Members Announce New Surcharge FMC Will Continue to Allow Carriers 30 Days to File New Service Contracts The U.S. Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) has issued an order that will extended the temporary exemption that allows ocean carriers up to thirty (30) days to file new service contracts with the Commission. In the interest of providing certainty and stability to supply chain stakeholders, the Commission believes it is necessary to extend this exemption until June 1, 2021. The temporary order issued under FMC Docket No. 20-06 was scheduled to expire December 31, 2020. The Commission has also voted to initiate a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) that will, if ultimately approved, make this temporary exemption permanent. The FMC’s decision to grant an extra 30 days to file new service contracts into its SERVCON database is similar to a decision issued in 2017 that allows service contract amendments to be filed in SERVCON within thirty (30) calendar days after the effective date. -

East Coast China 2--ECC2

Last Update Date: 30-Sep-2021 East Coast China 2--ECC2 Vessel Name EVER LEGION Vessel Name EVER LADEN Vessel Name EVER LENIENT Vessel Name EVER LOVELY Vessel/Voyage EVG / 044 Vessel/Voyage ELD / 151 Vessel/Voyage EVT / 061 Vessel/Voyage LVY / 040 Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Qingdao 13--13 Sep Qingdao 15--15 Sep Qingdao 22--21 Sep Qingdao 30-- Sep Ningbo 19--19 Sep Ningbo 20--21 Sep Ningbo 24--24 Sep Ningbo 02-- Oct Shanghai 23--23 Sep Shanghai 24--24 Sep Shanghai 30-- Sep Shanghai 04-- Oct Busan 28--27 Sep Busan 28--28 Sep Busan 04-- Oct Busan 06-- Oct Panama Canal 14-- Oct Panama Canal 14-- Oct Panama Canal 21-- Oct Panama Canal 22-- Oct Colon 15-- Oct Colon 15-- Oct Colon 22-- Oct Colon 23-- Oct Savannah 20-- Oct Savannah 20-- Oct Savannah 27-- Oct Savannah 28-- Oct Charleston 22-- Oct Charleston 22-- Oct Charleston 29-- Oct Charleston 30-- Oct Boston 25-- Oct Boston 25-- Oct Boston 01-- Nov Boston 02-- Nov New York 27-- Oct New York 27-- Oct New York 03-- Nov New York 04-- Nov Colon 03-- Nov Colon 03-- Nov Colon 10-- Nov Colon 11-- Nov Panama Canal 04-- Nov Panama Canal 04-- Nov Panama Canal 11-- Nov Panama Canal 12-- Nov Qingdao 21-- Nov Qingdao 23-- Nov Qingdao 02-- Dec Qingdao 07-- Dec Ningbo 24-- Nov Shanghai 26-- Nov Busan 28-- Nov Vessel Name EVER FAITH Vessel Name APL SOUTHAMPTON Vessel Name EVER FORE Vessel Name EVER FAST Vessel/Voyage FAH / 011 Vessel/Voyage SOU / 407 Vessel/Voyage EOR / 002 Vessel/Voyage EAV / 006 Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Port Arr--Dep Qingdao 11-- Oct Qingdao -

Volume Contracts of Affreightment – Some Features and Principles

Volume Contracts of Affreightment – Some Features and Principles Lars Gorton 1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………….…. 62 1.1 General Background ……………………………………………………… 62 1.2 Some Contractual Points …………..……………………………………... 62 1.3 Frame Agreements ………………………………………………………... 64 1.4 Some General Points Related to Distributorship Agreements and Volume Contracts ………………………………………. 66 1.5 Some Further Overriding Points ……………………………………….…. 67 2 Contract Forms ………………………………………………………………… 68 3 Law, Contract and Terminology ……………………………………………… 69 4 The SMC Rules on Volume Contracts ……………………………………..…. 70 5 Characteristics of COA’s ……………………………………………………… 71 6 The Generic Nature of the COA ………………………………………………. 72 7 Some of the Parameters of the COA ………………………...……………….. 76 7.1 The Ships Involved Under the Volume Contract ………………………… 76 7.2 Time Elements in Connection with COA’s ………………………………. 76 7.3 Cargo and Cargo Quantity and Planning of Voyages ………………….… 77 8 Breach and Consequences of Breach …………………………………………. 78 8.1 Generally, Best Efforts and Cooperation …………………………………. 78 8.2 Consequences of the Owners’s Breach …………………………………... 78 8.3 Consequences of the Charterer’s Breach …………………………………. 78 9 Some Comparisons with Distributorship Agreements in English Law ….…. 78 10 Some COA Cases Involving “Evenly spread” ……………………………….. 82 10.1 “Evenly spread” …………………………………………………………... 82 10.2 Mitigation of Damages …………………………………………………… 85 11 Freight, Demurrage and Similar ……………………………………………… 88 11.1 General Points ………..…………………………………………………... 88 11.2 Freight Level …………………………………………………………….. -

Federal Register/Vol. 70, No. 192/Wednesday, October 5, 2005

58222 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 192 / Wednesday, October 5, 2005 / Notices however, will be limited to the seating of the date this notice appears in the Parties: American President Lines, available. Unless so requested by the Federal Register. Copies of agreements Ltd.; APL Co. Pte Ltd.; China Shipping Council’s Chair, there will be no public are available through the Commission’s Container Lines Co., Ltd.; COSCO oral participation, but the public may Office of Agreements (202–523–5793 or Container Lines Company Limited; submit written comments to Jeffery [email protected]). Evergreen Marine Corporation (Taiwan), Goldthorp, the Federal Communications Agreement No.: 011223–031. Ltd.; Hanjin Shipping Co., Ltd.; Hapag- Commission’s Designated Federal Title: Transpacific Stabilization Lloyd Container Line GmbH; Kawasaki Officer for the Technological Advisory Agreement. Kisen Kaisha, Ltd.; Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Council, before the meeting. Mr. Parties: American President Lines, Ltd.; Hyundai Merchant Marine Co. Goldthorp’s e-mail address is Ltd.; APL Co. Pte Ltd.; CMA CGM, S.A.; Ltd.; Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd.; [email protected]. Mail delivery COSCO Container Lines Ltd.; Evergreen Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd.; Nippon Yusen address is: Federal Communications Marine Corp. (Taiwan) Ltd.; Hanjin Kaisha Line; Orient Overseas Container Commission, 445 12th Street, SW., Shipping Co., Ltd.; Hapag-Lloyd Line Limited; and Yangming Marine Room 7–A325, Washington, DC 20554. Container Linie GmbH; Hyundai Transport Corp. Merchant Marine Co., Ltd.; Kawasaki Filing Party: David F. Smith, Esq.; Federal Communications Commission. Kisen Kaisha, Ltd.; Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Sher & Blackwell; 1850 M Street, NW.; Marlene H. -

Exx Eagle Express X

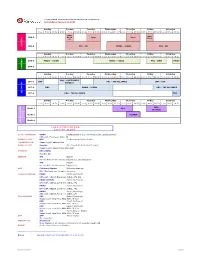

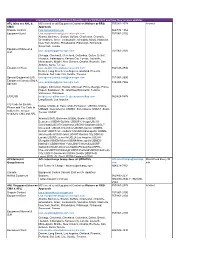

EXX EAGLE EXPRESS X APL’s premium China-to-Los Angeles service that goes the X-tra mile for you. EXPERIENCE THE X-CEPTIONAL TREATMENT YOU DESERVE EXX is APL’s premium weekly China to Los Angeles expedited ocean freight service with the “X factor”: Fast transit with next day cargo availability - 11 days from -PEDITED Shanghai; 12 days from Ningbo SHIPMENT Fully wheeled operations on-dock at TraPac Terminal with cargo directly discharged to chassis - just hook and go Dedicated EXX container yard and truck lanes for expedited cargo pick-up -CLUSIVE SPACE Space and box assured when loading from Asian ports - no rolls & EQUIPMENT New and guaranteed chassis from APL-dedicated pool GPS-enabled chassis for accurate tracking of asset location White glove service experience – from booking to delivery -TRAORDINARY and pick-up SERVICE Dedicated APL team managing your EXX shipment – always ready to support your shipment requirements and inquiries Proactive monitoring and notication of shipment status throughout the journey EXX-DEDICATED BOOKING DOCUMENTATION GATE IN / OUT CUSTOMER SUPPORT • Booking confirmation in • AMS cut-off: • CY open: [email protected] 30 minutes Shanghai Tue 11:00 Shanghai Mon 01:00 86-21-26105888 • Late booking available Ningbo Mon 10:30 Ningbo Thu 10:00 (Shanghai) upon request (subject to • VGM cut-off: • CY cut-off: 86-574-89071724 timely documentation) Shanghai Thu 01:00 Shanghai Wed 22:00 (Ningbo) Ningbo Tue 12:00 Ningbo Tue 11:00 • BL issuance: 4 work hours after vessel departure EXX-DEDICATED INVOICING PICK-UP SHIPMENT NOTIFICATION -

CONTAINER SERVICES BERTH WINDOW SCHEDULE Last Updated January 12, 2018

CONTAINER SERVICES BERTH WINDOW SCHEDULE Last Updated January 12, 2018 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30* 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 WEST WEST CEN-5 WOOD Barge Barge WOOD (2) CENTERM CEN-6 TP1 - 2M CPNW - OCEAN TP9 - 2M Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30* 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 VTM-5 PNW3 - OCEAN PNW1 - OCEAN PN2 - HMM PNW3 VTM-6 VANTERM Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30* 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 MSC - CALIFORNIA DPT-1 ZMP PN1 - THE ALLIANCE ZMP - ZIM EXPRESS DPT-2 PN2 PNW4 - OCEAN PN2 - THE ALLIANCE DELTAPORT DPT-3 PN3 - THE ALLIANCE PN3 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30* 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 1:00 8:00 16:30 MPS Berth 7 AL5 (MedPac) Berth 8 OCEANIA DOCKS Berth 9 FRASER SURREY FRASER L I N E / C O N S O R T I U M S e r v i c e N a m e COSCO SHIPPING CPWN (China/Canada & U.S. -

October 31St, 2016 to Whom It May Concern, Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha

October 31 st , 2016 To Whom it May Concern, Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. Eizo Murakami, President & CEO Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. Junichiro Ikeda, President & CEO Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha Tadaaki Naito, President Notice of Agreement to the Integration of Container Shipping Businesses Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd., Mitsui O.S.K. Lines Ltd., and Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha have agreed, after the resolution by the board of directors of each company held today, and subject to regulatory approval from the authorities, to establish a new joint-venture company to integrate the container shipping businesses (including worldwide terminal operating businesses excluding Japan) of all three companies and to sign a business integration contract and a shareholders agreement. 1. Background Although growing modestly, the container shipping industry has struggled in recent years due to a decline in the container growth rate and the rapid influx of newly built vessels. These two factors have contributed to an imbalance of supply and demand which has destabilized the industry and has created an environment that is adverse to container line profitability. In order to combat these factors, industry participants have sought to gain scale merit through mergers and acquisitions and consequently the structure of the industry is changing through consolidation. Under these circumstances, three companies have now decided to integrate their respective container shipping on an equal footing to ensure future stable, efficient and competitive business operations. The new joint-venture company is expected to create a synergy effect by utilizing the best practices of the three companies. And by taking advantage of scale merit of its vessel fleet totaling 1.4 million TEUs, realize integration effect of approximately 110 billion Japanese Yen annually and seek swiftly financial performance stabilization. -

APL (Also See ANL & CMA) MC's Need to Call Equipment Control on Waivers Or RRG Approvals 757/961-2574 Dispute Contact PSW

Frequently Called Equipment Providers as of 09/16/2021 and how they receive updates APL (also see ANL & MC’s need to call Equipment Control on Waivers or RRG 757/961-2574 Internet CMA) Approvals Dispute Contact [email protected] 866/574-1364 Equipment East [email protected] 757/961-2102 Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Buffalo, Charleston, Charlotte, Greensboro, Greer, Jacksonville, Memphis, Miami, Nashville, New York, Norfolk, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Richmond, Savannah, Tampa. Equipment Midwest & [email protected] 757/961-2105 Gulf Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Loredo, Louisville, Minneapolis, Mobile, New Orleans, Omaha, Rochelle, San Antonio, Santa Teresa. Equipment West [email protected] 602/586-4940 Denver, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Oakland, Phoenix, Portland, Salt Lake City, Seattle, Tacoma. Special Equipment (US) [email protected] 757/961-2600 Equipment Canada (Dry & [email protected] 514/908-7866 Special) Calgary, Edmonton, Halifax, Montreal, Prince George, Prince Rupert, Saskatoon, St. John/New Brunswick, Toronto, Vancouver, Winnipeg. LAX/LGB [email protected] Or [email protected] 562/624-5676 Long Beach, Los Angeles. City Code for Emails- Dallas: USDAL-El Paso: USELP-Houston: USHOU- Mobile: Please add City Code to USMOB- New Orleans: USMSY- San Antonio: USSAT- Santa subject line on your Tereas: USSXT emails for CMA and APL Atlanta:USATL-Baltimore:USBAL-Boston:USBOS- Bessemer:USBMV-Buffalo: USBUF-Chicago:USCHI- Cincinnatti:USCVG-Charleston:USCHS-Charlotte:USCLT- Cleveland: USCLE-Columbus:USCMH-Denver:USDEN- Detroit: USDET-Greensboro: USGBO-Indianapolis: USIND- Jacksonville:USJAX-Joliet: USJOT-Kansas City:USKCK- Laredo:USLRD-Louisville:USLUI-Los Angeles:USLAX- Memphis:USMEM-Miami:USMIA-Minneapolis:USMES- Nashville:USBNA-New York:USNYC-Norfolk:USORF- Oakland:USOAK-Omaha:USOMA-Phildelphia:USPHL- Phoenix:USPHX-Pittsburgh:USPIT-Portland:USPDX-Salt Lake City: USSLC-Savannah:USSAV-Seattle:USSEA-St.