Lambert Review of Business-University Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Learning in American Higher Education: Strategies for Developing Global Citizens in an Era of Complex Interdependence

Innovation, Technology, and Knowledge Management Series Editor Elias G. Carayannis, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/8124 Andreas Altmann • Bernd Ebersberger Editors Universities in Change Managing Higher Education Institutions in the Age of Globalization 123 Editors Andreas Altmann Bernd Ebersberger MCI Management Center Innsbruck—The MCI Management Center Innsbruck—The Entrepreneurial School Entrepreneurial School Innsbruck Innsbruck Austria Austria ISBN 978-1-4614-4589-0 ISBN 978-1-4614-4590-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-4590-6 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012946186 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. -

College Employer Satisfaction League Table

COLLEGE EMPLOYER SATISFACTION LEAGUE TABLE The figures on this table are taken from the FE Choices employer satisfaction survey taken between 2016 and 2017, published on October 13. The government says “the scores calculated for each college or training organisation enable comparisons about their performance to be made against other colleges and training organisations of the same organisation type”. Link to source data: http://bit.ly/2grX8hA * There was not enough data to award a score Employer Employer Satisfaction Employer Satisfaction COLLEGE Satisfaction COLLEGE COLLEGE responses % responses % responses % CITY COLLEGE PLYMOUTH 196 99.5SUSSEX DOWNS COLLEGE 79 88.5 SANDWELL COLLEGE 15678.5 BOLTON COLLEGE 165 99.4NEWHAM COLLEGE 16088.4BRIDGWATER COLLEGE 20678.4 EAST SURREY COLLEGE 123 99.2SALFORD CITY COLLEGE6888.2WAKEFIELD COLLEGE 78 78.4 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE 205 99.0CITY COLLEGE BRIGHTON AND HOVE 15088.0CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE6178.3 NORTHBROOK COLLEGE SUSSEX 176 98.9NORTHAMPTON COLLEGE 17287.8HEREFORDSHIRE AND LUDLOW COLLEGE112 77.8 ABINGDON AND WITNEY COLLEGE 147 98.6RICHMOND UPON THAMES COLLEGE5087.8LINCOLN COLLEGE211 77.7 EXETER COLLEGE 201 98.5CHESTERFIELD COLLEGE 20687.7WEST NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE242 77.4 SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE AND STROUD COLLEGE 215 98.1ACCRINGTON AND ROSSENDALE COLLEGE 14987.6BOSTON COLLEGE 61 77.0 TYNE METROPOLITAN COLLEGE 144 97.9NEW COLLEGE DURHAM 22387.5BURY COLLEGE121 76.9 LAKES COLLEGE WEST CUMBRIA 172 97.7SUNDERLAND COLLEGE 11487.5STRATFORD-UPON-AVON COLLEGE5376.9 SWINDON COLLEGE 172 97.7SOUTH -

Innovate-UK-Energy-Catalyst-Round-4-Directory-Of-Projects

Directory of projects Energy Catalyst – Round 4 1 Introduction Energy markets around the world – private and public, household and industry, developed and developing – are all looking for solutions to the same problem: how to provide a resilient energy system that delivers affordable and clean energy with access for all. Solving this trilemma requires innovation and collaboration on an international scale and UK businesses and researchers are at the forefront of addressing the energy revolution. Innovate UK is the UK’s innovation agency. We work with business, policy-makers and the research base to help support the development of new ideas, technologies, products and services, and to help companies de-risk their innovations as they journey towards commercialisation and business growth. The Energy Catalyst was established as a national open competition, run by Innovate UK and co-funded with the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Department for International Development (DFID). Since 2013, the Energy Catalyst has invested almost £100m in grant funding across more than 750 organisations and 250 projects. The Energy Catalyst exists to accelerate development, commercialisation and deployment of the very best of UK energy technology and business innovation. Support from the Energy Catalyst has enabled many companies to validate their technology and business propositions, to forge key supply-chain partnerships, to accelerate their growth and to secure investment for the next stages of their business development. Affordable access to clean and reliable energy supplies is a key requirement for sustainable and inclusive economic growth. With funding through DFID’s “Transforming Energy Access” programme, the Energy Catalyst is helping UK energy innovators to forge new international partnerships, and directly address the energy access needs of poor households, communities and enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. -

The Further Education and Sixth-Form Colleges

Liverpool City Region Area Review Final Report January 2017 Contents Background 4 The needs of the Liverpool City Region area 5 Demographics and the economy 5 Patterns of employment and future growth 9 LEP priorities 12 Feedback from LEPs, employers, local authorities, students and staff 13 The quantity and quality of current provision 16 Performance of schools at Key Stage 4 17 Schools with sixth-forms 17 The further education and sixth-form colleges 18 The current offer in the colleges 20 Quality of provision and financial sustainability of colleges 21 Higher education in further education 22 Provision for students with special educational needs and disability (SEND) and high needs 23 Apprenticeships and apprenticeship providers 24 Land based provision 25 The need for change 26 The key areas for change 28 Initial options raised during visits to colleges 28 Criteria for evaluating options and use of sector benchmarks 30 Assessment criteria 30 FE sector benchmarks 30 Recommendations agreed by the steering group 32 Birkenhead Sixth Form College 33 Carmel College 34 Knowsley Community College and St Helens College 34 City of Liverpool College 35 Hugh Baird College, South Sefton College, Southport College and King George V Sixth Form College 36 Riverside College 38 2 Wirral Metropolitan College 38 Apprenticeship Growth Plan 39 Prospectus of advanced and higher level technical skills 40 Sector-facing provision that meets employer needs 40 Institute of Technology 40 Needs of SEND post-16 learners 41 Entry routes for learners with low level skills 42 Careers hub 42 Enhanced post-16 options 43 Strategic planning and oversight group 43 Conclusions from this review 44 Next steps 46 3 Background In July 2015, the government announced a rolling programme of around 40 local area reviews, to be completed by March 2017, covering all general further education and sixth- form colleges in England. -

Framework Users (Clients)

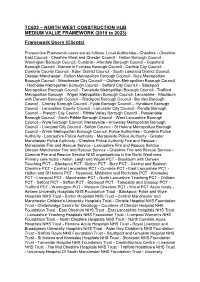

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

Access and Participation Plan 2019 - 2020 Contents: Page

Access and Participation Plan 2019 - 2020 Contents: Page: 1. Introduction 3 2. Financial support for students 7 3. Access and student success measures 8 4. Targets and milestones 18 5. Monitoring and evaluation arrangements 19 6. Equality and diversity 21 7. Provision of information to prospective students 22 8. Consultation with students 23 St Helens College (trading as SK College Group) 2 1. Introduction St Helens College merged with Knowsley Community College in December 2017 and is currently trading as SK College Group. University Centre St Helens is the branding name used to cover the higher education provision at both campuses. Based in the heart of the Northwest, UCSH is in an ideal location with strong transport links and just 20–30 minutes from both Liverpool and Manchester city centres. The merger with Knowsley Community College, brings with it increased opportunities for local progression to higher education, along with increased specialist resources and staff expertise. This commitment to the continued development of HE in St Helens and the growth of HE opportunities in Knowsley was identified as a key feature of the merger and welcomed by both the local and business communities to raise aspirations and levels of skill in each borough. The College Group’s Higher Education Strategy takes account of national policies relating to Widening Participation and articulates the College Group’s plans for stimulating demand in HE, in what is a more student–led market, and to meet regional and local workforce development needs through a more innovative curriculum and a revised marketing approach. The Strategy also sets out a plan for maintaining the current success and satisfaction rates and increasing the emphasis on progression and employability. -

The Parthenon Sculptures Sarah Pepin

BRIEFING PAPER Number 02075, 9 June 2017 By John Woodhouse and Sarah Pepin The Parthenon Sculptures Contents: 1. What are the Parthenon Sculptures? 2. How did the British Museum acquire them? 3. Ongoing controversy 4. Further reading www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Parthenon Sculptures Contents Summary 3 1. What are the Parthenon Sculptures? 5 1.1 Early history 5 2. How did the British Museum acquire them? 6 3. Ongoing controversy 7 3.1 Campaign groups in the UK 9 3.2 UK Government position 10 3.3 British Museum position 11 3.4 Greek Government action 14 3.5 UNESCO mediation 14 3.6 Parliamentary interest 15 4. Further reading 20 Contributing Authors: Diana Perks Attribution: Parthenon Sculptures, British Museum by Carole Radatto. Licenced under CC BY-SA 2.0 / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 9 June 2017 Summary This paper gives an outline of the more recent history of the Parthenon sculptures, their acquisition by the British Museum and the long-running debate about suggestions they be removed from the British Museum and returned to Athens. The Parthenon sculptures consist of marble, architecture and architectural sculpture from the Parthenon in Athens, acquired by Lord Elgin between 1799 and 1810. Often referred to as both the Elgin Marbles and the Parthenon marbles, “Parthenon sculptures” is the British Museum’s preferred term.1 Lord Elgin’s authority to obtain the sculptures was the subject of a Select Committee inquiry in 1816. It found they were legitimately acquired, and Parliament then voted the funds needed for the British Museum to acquire them later that year. -

Post 16 Provision Update for Local Offer

Preparing for Adulthood – Post 16 update for Local Offer The information below has been taken from the websites listed, which was written by the individual providers. This list does not reflect any endorsement by Halton Borough Council. It is merely a list of known providers to provide basic information about Post 16 Provision. Provision Contact Details Ashley School - Halton Mike Jones Head of 6th Form Maintained Special School Ashley High School Ashley High School 6th Form provides specialist Cawfield Avenue education for boys and girls, aged 16 to 19, with Widnes Asperger's Syndrome, higher-functioning autism and Cheshire social communication difficulties. The 6th form focus is WA8 7HG on continued core academic qualifications, a range of 0151 424 4892 vocational qualifications, preparation for adulthood and [email protected] career planning, whilst recognising the individual abilities and strengths of each student and enabling www.ashleyhighschool.co.uk them to reach their full potential. Bolton College – Greater Manchester Janet Bishop College of Further Education Head of Learner Support Bolton college provides high quality learning Bolton College opportunities and support throughout the curriculum, to Deane Road Bolton BL3 5BG learners with a wide range of disabilities and learning 01204 482654 difficulties including visual and hearing impairments, [email protected] mental health and emotional difficulties and autism. Learners can access a variety of vocational and www.boltoncollege.ac.uk/ prevocational courses -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

Hpge) Detectors at Elevated Temperatures

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2015 Characterization of Mechanically Cooled High Purity Germanium (HPGe) Detectors at Elevated Temperatures Joseph Benjamin McCabe University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Nuclear Engineering Commons Recommended Citation McCabe, Joseph Benjamin, "Characterization of Mechanically Cooled High Purity Germanium (HPGe) Detectors at Elevated Temperatures. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3350 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Joseph Benjamin McCabe entitled "Characterization of Mechanically Cooled High Purity Germanium (HPGe) Detectors at Elevated Temperatures." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Nuclear Engineering. Jason Hayward, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Eric Lukosi, -

Stuart Siddall, Chief Executive of the Act, Outlines the Themes and Content of the 2010 Annual Conference

act ANNUAL CONFERENCE STUART SIDDALL, CHIEF EXECUTIVE OF THE ACT, OUTLINES THE THEMES AND CONTENT OF THE 2010 ANNUAL CONFERENCE. Shaping the future he ACT Annual Conference 2010 offers an unrivalled forum Developments, EDF Energy, Invensys and Shell – and the participation for treasurers and fellow finance professionals to focus on of other corporate treasurers in the structured discussions. opportunities in the current business climate. This is clearly Contributors from a range of banks and other professional firms will reflected in the conference theme: Shaping the Future. also be adding their considerable experience and expertise. The range TThe structure of the conference has benefitted greatly from very of topics includes alternative funding, holistic risk management and positive feedback on last year’s event. In response to the ever opportunities in corporate M&A activity. growing demands on delegates’ time, the event has been shortened The conference will also feature what is fast becoming an ACT to two concentrated days of learning, discussion and interaction. Our tradition: a Question Time panel discussion, chaired this year by aim is to allow treasurers to gain from the experiences of their peers broadcaster and journalist Mishal Husain, and with a panel including and those in related disciplines. X-Leisure’s chief executive PY Gerbeau and Lloyds Banking Group’s The conference’s plenary sessions include high-level strategic chief economist Trevor Williams. presentations, with keynote addresses from economist Tim Congdon The ACT knows that treasurers and other finance professionals are CBE and Richard Lambert, director-general of the CBI. These sessions faced with a greater range of challenges than ever before. -

Program and Abstracts CONFERENCE COMMITTEE

ICC 19 San Diego, CA · June 20-23, 2016 P Program and Abstracts CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Conference Chairman Program Committee Dean Johnson Carl Kirkconnell, West Coast Solutions, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USA USA - Chair Email: [email protected] Mark Zagarola, Creare, USA, - Deputy Chair Conference Co-Chairmen Tonny Benchop, Thales Cryogenics BV, Netherlands Jose Rodriguez Peter Bradley, NIST, USA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USA Ted Conrad, Raytheon, USA Email: [email protected] Gershon Grossman, Technion, Israel Elaine Lim, Aerospace Corporation, USA Sidney Yuan Jennifer Marquardt, Ball Aerospace, Aerospace Corporation, USA USA Jeff Olson, Lockheed Martin, USA Email : [email protected] John Pfotenhauer, University of Wisconsin – Madison, USA Treasurer Alex Veprik, SCD, Israel Ray Radebaugh Sonny Yi, Aerospace Corporation, USA National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), USA ICC Board Email: [email protected] Dean Johnson, JPL, USA-Chairman Ray Radebaugh, NIST, USA – Treasurer Proceedings Co-editors Ron Ross, JPL, USA – Co-Editor Saul Miller Jeff Raab, Retired, USA – Past Chairman Retired Rich Dausman, Cryomech, Inc., USA - Email: icc [email protected] Past Chairman Paul Bailey, University of Oxford, UK Peter Bradley, NIST, USA Ron Ross Martin Crook, RAL, UK Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USA Lionel Duband, CEA, France Email: [email protected] Zhihua Gan, Zhejiang University, China Ali Kashani, Atlas Scientific, USA Takenori Numezawa, National Institute for Program Chair Material Science, Japan Carl Kirkconnell Jeff Olson, Lockheed Martin Space System West Coast Solutions, USA Co., USA Email: [email protected] Limin Qiu, Zhejiang University, China Thierry Trollier, Absolut System SAS, Deputy Program Chair France Mark Zagarola, Creare, USA Mark V.