1 WHAT IF REYNOLDS LIVED and OTHER UNION WHAT-IFS for the BATTLE of GETTYSBURG? Terrence L. Salada and John D. Wedo Was The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carl Schurz's Contribution to the Lincoln Legend

Volume 18 No 1 • Spring 2009 Carl Schurz’s Contribution to the Lincoln Legend Cora Lee Kluge LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LC-5129 CONGRESS, OF LIBRARY LC-9301 CONGRESS, OF LIBRARY Carl Schurz, undated Abraham Lincoln, 1863 mong all the works about of approximately 22,000 words is INSIDE Abraham Lincoln that too long to be a book review and are currently available at the same time surprisingly short Ain this Lincoln bicentennial year, for the well-respected assessment • MKI 25th Anniversary including both new titles and new of Lincoln and his presidency that Banquet and Conference editions of older titles, one contri- it has become. It was republished • Letters of a German in bution that catches our attention repeatedly between 1891 and 1920 the Confederate Army is an essay by Carl Schurz that first and several times since, includ- • Citizens and Those Who appeared in 1891. Written origi- ing at least three times in German Leave, Book Review nally as a response to the Atlantic translation (1908, 1949, 1955), and • Rembering Robert M. Bolz Monthly’s request for a review of now has appeared in new editions • Racial Divides, Book Review the new ten-volume Abraham Lin- (2005, 2007, and twice in 2008), coln: A History by John G. Nicolay and John Hay (1891), this essay Continued on page 11 DIRECTOR’S CORNER Greetings, Friends Our online course “The German- diaries of the Milwaukee panorama American Experience,” a joint project painter F. W. Heine. Second is the and Readers! of the Wisconsin Alumni Asso- project entitled “Language Matters ciation, the Division of Continuing for Wisconsin” (Center for the Study Studies, and the Max Kade Institute, of Upper Midwestern Cultures, MKI, pring is here—almost—and is in full swing. -

R-456 Page 1 of 1 2016 No. R-456. Joint Resolution Supporting The

R-456 Page 1 of 1 2016 No. R-456. Joint resolution supporting the posthumous awarding of the Congressional Medal of Honor to Civil War Brigadier General George Jerrison Stannard. (J.R.H.28) Offered by: Representatives Turner of Milton, Hubert of Milton, Johnson of South Hero, Krebs of South Hero, Devereux of Mount Holly, Branagan of Georgia, Jerman of Essex, and Troiano of Stannard Whereas, Civil War Brigadier General George Jerrison Stannard, a native of Georgia, Vermont, commanded the Second Vermont Brigade, and Whereas, the Second Vermont Brigade (Stannard’s Brigade), untested in battle, reached Gettysburg on July 1, 1863 at the end of the first day’s fighting, and Whereas, Stannard’s Brigade fought ably late on the battle’s second day, helping to stabilize the threatened Union line, and earning it a place at the front of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, and Whereas, on the battle’s final day, in perhaps the most memorable Confederate maneuver of the Civil War that became known as Pickett’s Charge, the Confederate troops approached the Union line, but they suddenly shifted their direction northward, leaving no enemy troops in front of the Vermonters, and Whereas, General Stannard recognized this unexpected opportunity and ordered the Brigade’s 13th and 16th regiments to “change front forward on first company,” sending 900 Vermonters in a great wheeling motion to the front of the Union lines, and Whereas, Stannard’s men hit the exposed right flank of Pickett’s Charge in an attack the Confederates did not expect, inflicting hundreds of casualties, and Whereas, Major Abner Doubleday, commanding the Army of the Potomac’s I Corps, in which the Vermonters served, commented that General Stannard’s strategy helped to ensure, if not guarantee, the Union’s victory at Gettysburg, and Whereas, Confederate General Robert E. -

Battle of Gettysburg Day 1 Reading Comprehension Name: ______

Battle of Gettysburg Day 1 Reading Comprehension Name: _________________________ Read the passage and answer the questions. The Ridges of Gettysburg Anticipating a Confederate assault, Union Brigadier General John Buford and his soldiers would produce the first line of defense. Buford positioned his defenses along three ridges west of the town. Buford's goal was simply to delay the Confederate advance with his small cavalry unit until greater Union forces could assemble their defenses on the three storied ridges south of town known as Cemetery Ridge, Cemetery Hill, and Culp's Hill's. These ridges were crucial to control of Gettysburg. Whichever army could successfully occupy these heights would have superior position and would be difficult to dislodge. The Death of Major General Reynolds The first of the Confederate forces to engage at Gettysburg, under the Command of Major General Henry Heth, succeeded in advancing forward despite Buford's defenses. Soon, battles erupted in several locations, and Union forces would suffer severe casualties. Union Major General John Reynolds would be killed in battle while positioning his troops. Major General Abner Doubleday, the man eventually credited with inventing the formal game of baseball, would assume command. Fighting would intensify on a road known as the Chambersburg Pike, as Confederate forces continued to advance. Jubal Early's Successful Assault Meanwhile, Union defenses positioned north and northwest of town would soon be outflanked by Confederates under the command of Jubal Early and Robert Rodes. Despite suffering severe casualties, Early's soldiers would break through the line under the command of Union General Francis Barlow, attacking them from multiple sides and completely overwhelming them. -

Battle-Of-Waynesboro

Battlefield Waynesboro Driving Tour AREA AT WAR The Battle of Waynesboro Campaign Timeline 1864-1865: Jubal Early’s Last Stand Sheridan’s Road The dramatic Union victory at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, had effectively ended to Petersburg Confederate control in the Valley. Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early “occasionally came up to the front and Winchester barked, but there was no more bite in him,” as one Yankee put it. Early attempted a last offensive in mid- October 19, 1864 November 1864, but his weakened cavalry was defeated by Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s cavalry at Kernstown Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan Newtown (Stephens City) and Ninevah, forcing Early to withdraw. The Union cavalry now so defeats Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early at Cedar Creek. overpowered his own that Early could no longer maneuver offensively. A Union reconnaissance Strasburg Front Royal was repulsed at Rude’s Hill on November 22, and a second Union cavalry raid was turned mid-November 1864 back at Lacey Spring on December 21, ending active operations for the winter season. Early’s weakened cavalry The winter was disastrous for the Confederate army, which was no longer able is defeated in skirmishes at to sustain itself on the produce of the Valley, which had been devastated by Newtown and Ninevah. the destruction of “The Burning.” Rebel cavalry and infantry were returned November 22, to Lee’s army at Petersburg or dispersed to feed and forage for themselves. 1864 Union cavalry repulsed in a small action at Rude’s Hill. Prelude to Battle Harrisonburg December 21, McDowell 1864 As the winter waned and spring approached, Confederates defeat Federals the Federals began to move. -

Buford-Duke Family Album Collection, Circa 1860S (001PC)

Buford-Duke Family Album Collection, circa 1860s (001PC) Photograph album, ca. 1860s, primarily made up of CDVs but includes four tintypes, in which almost all of the images are identified. Many of the persons identified are members of the Buford and Duke families but members of the Taylor and McDowell families are also present. There are also photographs of many Civil War generals and soldiers. Noted individuals include George Stoneman, William Price Sanders, Phillip St. George Cooke, Ambrose Burnside, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, George Gordon Meade, Napoleon Bonaparte Buford, George Brinton McClellan, Wesley Merritt, John Buford, Winfred Scott Hancock, John C. Fremont, Green Clay Smith, Basil Wilson Duke, Philip Swigert, John J. Crittenden and Davis Tillson. The photographs are in good condition but the album cover is coming apart and is in very poor condition and the album pages range from fair to good condition. A complete list of the identified persons is as follows: Buford-Duke, 1 Buford-Duke Family Album Collection, circa 1860s (001PC) Page 1: Page 4 (back page): Top Left - George Stoneman Captain Joseph O'Keefe (?) Top Right - Mrs. Stoneman Captain Myles W. Keogh (?) Bottom Left - William Price Sanders A. Hand Bottom Right Unidentified man Dr. E. W. H. Beck Page 1 (back page): Page 5: Mrs. Coolidge Mrs. John Buford Dr. Richard Coolidge John Buford Phillip St. George Cooke J. Duke Buford Mrs. Phillip St. George Cooke Watson Buford Page 2: Page 5 (back page): John Cooke Captain Theodore Bacon (?) Sallie Buford Bell Unidentified man Julia Cooke Fanny Graddy (sp?) Unidentified woman George Gordon Meade Page 2 (back page): Page 6: John Gibbon Unidentified woman Gibbon children D. -

Lincoln's Role in the Gettysburg Campaign

LINCOLN'S ROLE IN THE GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN By EDWIN B. CODDINGTON* MOST of you need not be reminded that the battle of Gettys- burg was fought on the first three days of July, 1863, just when Grant's siege of Vicksburg was coming to a successful con- clusion. On July 4. even as Lee's and Meade's men lay panting from their exertions on the slopes of Seminary and Cemetery Ridges, the defenders of the mighty fortress on the Mississippi were laying down their arms. Independence Day, 1863, was, for the Union, truly a Glorious Fourth. But the occurrence of these two great victories at almost the same time raised a question then which has persisted up to the present: If the triumph at Vicksburg was decisive, why was not the one at Gettysburg equally so? Lincoln maintained that it should have been, and this paper is concerned with the soundness of his supposition. The Gettysburg Campaign was the direct outcome of the battle of Chancellorsville, which took place the first week in May. There General Robert E. Lee won a victory which, according to the bookmaker's odds, should have belonged to Major General "Fight- ing Joe" Hooker, if only because Hooker's army outnumbered the Confederates two to one and was better equipped. The story of the Chancel'orsville Campaign is too long and complicated to be told here. It is enough to say that Hooker's initial moves sur- prised his opponent, General Lee, but when Lee refused to react to his strategy in the way he anticipated, Hooker lost his nerve and from then on did everything wrong. -

Sacred Ties: from West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: a True Story of the American Civil War

Civil War Book Review Summer 2010 Article 12 Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the American Civil War Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Hsieh, Wayne Wei-siang (2010) "Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the American Civil War," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol12/iss3/12 Hsieh: Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A Tr Review Hsieh, Wayne Wei-siang Summer 2010 Carhart, Tom Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the American Civil War. Berkley Caliber, 978-0-425-23421-1 ISBN 978-0-425-23421-1 Bonds of Brotherhood Tom Carhart, himself a West Point graduate and twice-wounded Vietnam veteran, has written a new study of the famous West Point Classes of 1860 and 1861. Carhart chooses to focus on four notable graduates from the Classes of 1861 (Henry Algernon DuPont, John Pelham, Thomas Lafayette Rosser, and George Armstrong Custer), and two from the Class of 1860 (Wesley Merritt and Stephen Dodson Ramseur). Carhart focuses on the close bonds formed between these cadets at West Point, which persisted even after the division of both the nation and the antebellum U.S. Army officer corps during the Civil War. He starts his narrative with a shared (and illicit) drinking party at Benny’s Haven, a nearby tavern and bane of the humorless guardians of cadet discipline at what is sometimes now not-so-fondly described as the South Hudson Institute of Technology. -

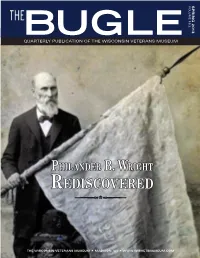

Rediscovered

VOLUME 19:2 2013 SPRING QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM PHILANDER B. WRIGHT REDISCOVERED THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM FROM THE SECRETARY sure there was strong support Exhibit space was quickly for the museum all around the filled, as relics from those state, from veterans and non- subsequent wars vastly veterans alike. enlarged our collections and How the Wisconsin Veterans the museum became more Museum came to be on the and more popular. By the Capitol Square in its current 1980s, it was clear that our incarnation is best answered museum needed more space by the late Dr. Richard Zeitlin. for exhibits and visitors. Thus, As the former curator of the with the support of many G.A.R. Memorial Hall Museum Veterans Affairs secretaries, in the State Capitol and the Governor Thompson and Wisconsin War Museum at the many legislators, we were Wisconsin Veterans Home, he able to acquire the space and was a firsthand witness to the develop the exhibits that now history of our museum. make the Wisconsin Veterans Zeitlin pointed to a 1901 Museum a premiere historical law that mandated that state attraction in the State of officials establish a memorial Wisconsin. WDVA SECRETARY JOHN SCOCOS dedicated to commemorating The Wisconsin Department Wisconsin’s role in the Civil of Veterans Affairs is proud FROM THE SECRETARY War and any subsequent of our museum and as we Greetings! The Wisconsin war as a starting point for commemorate our 20th Veterans Museum as you the museum. After the State anniversary in its current know it today opened on Capitol was rebuilt following location, we are also working June 6, 1993. -

Did Meade Begin a Counteroffensive After Pickett's Charge?

Did Meade Begin a Counteroffensive after Pickett’s Charge? Troy D. Harman When examining the strategy of Union Major General George Gordon Meade at the battle of Gettysburg, one discovers lingering doubts about his leadership and will to fight. His rivals viewed him as a timid commander who would not have engaged at Gettysburg had not his peers corralled him into it. On the first day of the battle, for instance, it was Major General John Fulton Reynolds who entangled the left wing of the federal army thirty miles north of its original defensive position at Westminster, Maryland. Under the circumstances, Meade scrambled to rush the rest of his army to the developing battlefield. And on the second day, Major General Daniel Sickles advanced part of his Union 3rd Corps several hundred yards ahead of the designated position on the army’s left, and forced Meade to over-commit forces there to save the situation. In both instances the Union army prevailed, while the Confederate high command struggled to adjust to uncharacteristically aggressive Union moves. However, it would appear that both outcomes were the result of actions initiated by someone other than Meade, who seemed to react well enough. Frustrating to Meade must have been that these same two outcomes could have been viewed in a way more favorable to the commanding general. For example, both Reynolds and Sickles were dependent on Meade to follow through with their bold moves. Though Reynolds committed 25,000 Union infantry to fight at Gettysburg, it was Meade who authorized his advance into south-central Pennsylvania. -

Gettysburg: Three Days of Glory Study Guide

GETTYSBURG: THREE DAYS OF GLORY STUDY GUIDE CONFEDERATE AND UNION ORDERS OF BATTLE ABBREVIATIONS MILITARY RANK MG = Major General BG = Brigadier General Col = Colonel Ltc = Lieutenant Colonel Maj = Major Cpt = Captain Lt = Lieutenant Sgt = Sergeant CASUALTY DESIGNATION (w) = wounded (mw) = mortally wounded (k) = killed in action (c) = captured ARMY OF THE POTOMAC MG George G. Meade, Commanding GENERAL STAFF: (Selected Members) Chief of Staff: MG Daniel Butterfield Chief Quartermaster: BG Rufus Ingalls Chief of Artillery: BG Henry J. Hunt Medical Director: Maj Jonathan Letterman Chief of Engineers: BG Gouverneur K. Warren I CORPS MG John F. Reynolds (k) MG Abner Doubleday MG John Newton First Division - BG James S. Wadsworth 1st Brigade - BG Solomon Meredith (w) Col William W. Robinson 2nd Brigade - BG Lysander Cutler Second Division - BG John C. Robinson 1st Brigade - BG Gabriel R. Paul (w), Col Samuel H. Leonard (w), Col Adrian R. Root (w&c), Col Richard Coulter (w), Col Peter Lyle, Col Richard Coulter 2nd Brigade - BG Henry Baxter Third Division - MG Abner Doubleday, BG Thomas A. Rowley Gettysburg: Three Days of Glory Study Guide Page 1 1st Brigade - Col Chapman Biddle, BG Thomas A. Rowley, Col Chapman Biddle 2nd Brigade - Col Roy Stone (w), Col Langhorne Wister (w). Col Edmund L. Dana 3rd Brigade - BG George J. Stannard (w), Col Francis V. Randall Artillery Brigade - Col Charles S. Wainwright II CORPS MG Winfield S. Hancock (w) BG John Gibbon BG William Hays First Division - BG John C. Caldwell 1st Brigade - Col Edward E. Cross (mw), Col H. Boyd McKeen 2nd Brigade - Col Patrick Kelly 3rd Brigade - BG Samuel K. -

Course Reader

Course Reader Gettysburg: History and Memory Professor Allen Guelzo The content of this reader is only for educational use in conjunction with the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Teacher Seminar Program. Any unauthorized use, such as distributing, copying, modifying, displaying, transmitting, or reprinting, is strictly prohibited. GETTYSBURG in HISTORY and MEMORY DOCUMENTS and PAPERS A.R. Boteler, “Stonewall Jackson In Campaign Of 1862,” Southern Historical Society Papers 40 (September 1915) The Situation James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania,” in Annals of the War (Philadelphia, 1879) 1863 “Letter from Major-General Henry Heth,” SHSP 4 (September 1877) Lee to Jefferson Davis (June 10, 1863), in O.R., series one, 27 (pt 3) Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (Edinburgh, 1879) John S. Robson, How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War (Durham, NC, 1898) George H. Washburn, A Complete Military History and Record of the 108th Regiment N.Y. Vols., from 1862 to 1894 (Rochester, 1894) Thomas Hyde, Following the Greek Cross, or Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (Boston, 1894) Spencer Glasgow Welch to Cordelia Strother Welch (August 18, 1862), in A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to His Wife (New York, 1911) The Armies The Road to Richmond: Civil War Memoirs of Major Abner R. Small of the Sixteenth Maine Volunteers, ed. H.A. Small (Berkeley, 1939) Mrs. Arabella M. Willson, Disaster, Struggle, Triumph: The Adventures of 1000 “Boys in Blue,” from August, 1862, until June, 1865 (Albany, 1870) John H. Rhodes, The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, in the War to Preserve the Union (Providence, 1894) A Gallant Captain of the Civil War: Being the Record of the Extraordinary Adventures of Frederick Otto Baron von Fritsch, ed. -

Daniel Sickles Decisions at Gettysburg Student Guide Sheet Pdf File

“But General Meade this is higher ground!” - Daniel Sickles , July 2 1863 General Daniel Sickles was the commander of the Northern army’s 3rd or (III) corps (you say it “ kore ”) . The army was divided into 7 corps - each corps had about 10,000 men. Commanding General George Meade told General Sickles to move the 3rd Corps into a line of battle along the southern end of Cemetery Ridge and ending at Little Round Top. The Southern army was, of course, near by on Seminary Ridge. Fresh from their victory on July 1, General Robert E. Lee and the Southern army were sure to attack again on July the 2nd - but where? Comment [1]: rfinkill: this map shows the positions of both armies at the start of July 2, the Roman numerals are the number for each corps. When General Sickles arrived with his men at the position assigned to them by General Meade, he did not like it very much. The area in between Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top was lower ground and not a very good position Sickles felt. He will decide to move his corp of 10,000 men forward. Comment [2]: rfinkill: keep reading below... Click on this link and watch video #10 to find out some of Sickles reasons for moving forward...a s you watch think about what he intended to have happen when he Comment [3]: rfinkill: scroll down on the web site to find video 10 made this move forward This move by General Sickles does not make General Meade happy at all.