Roman Mythological Allusions and Organic Unity in Romeo and Juliet Kelsey Rhea Taylor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeoacoustics: a Key Role of Echoes at Utah Rock Art Sites

Steven J. Waller ARCHAEOACOUSTICS: A KEY ROLE OF ECHOES AT UTAH ROCK ART SITES Archaeoacoustics is an emerging field of study emanate from rock surfaces where beings are investigating sound in relation to the past. The depicted, as if the images are speaking. Myths intent of this paper is to convey appreciation for attribute echoes to sheep, humans, lizards, the echoes at Utah rock art sites, by recognizing snakes and other figures that are major rock art the importance of their influence both on the themes. Echo-rich Fremont Indian State Park ancient artists, and on modern scientific studies. even has a panel that has been interpreted as The title of this paper is thus intentionally showing the mythological Echo Twin. The worded such that it could be understood in two study, appreciation, and preservation of rock art different but interrelated ways. One, the study acoustics in Utah are encouraged. of sound indicates that echoes were an im- portant factor relative to rock art in Utah. Two, INITIAL STUDIES OUTSIDE UTAH the echoes found to be associated with Utah rock art sites have been particularly helpful in A conceptual connection between sound and developing theories relating sound to past cul- rock art originally occurred to me when visiting tural activities and ideologies. This paper de- European Palaeolithic caves in 1987. A fortui- scribes in a roughly chronological order the tous shout at the mouth of a cave resulted in a events and studies that have led to Utah featur- startling echo. I immediately remembered the ing prominently in the development of archaeo- Greek myth in which echoes were attributed to acoustics. -

BENVOLIO but New Struck Nine. ROMEO Ay Me! Sad Hours Seem Long

BENVOLIO/ROMEO BENVOLIO Good-morrow, cousin. ROMEO Is the day so young? BENVOLIO But new struck nine. ROMEO Ay me! sad hours seem long. Was that my father that went hence so fast? BENVOLIO It was. What sadness lengthens Romeo's hours? ROMEO Not having that, which, having, makes them short. BENVOLIO In love? ROMEO Out-- BENVOLIO Of love? ROMEO Out of her favour, where I am in love. BENVOLIO Alas, that love, so gentle in his view, Should be so tyrannous and rough in proof! ROMEO Alas, that love, whose view is muffled still, Should, without eyes, see pathways to his will! BENVOLIO Tell me in sadness, who is that you love. ROMEO What, shall I groan and tell thee? BENVOLIO Groan! why, no. But sadly tell me who. ROMEO In sadness, cousin, I do love a woman. BENVOLIO I aim'd so near, when I supposed you loved. ROMEO/JULIET ROMEO [To JULIET] If I profane with my unworthiest hand This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this: My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss. JULIET Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much, Which mannerly devotion shows in this; For saints have hands that pilgrims' hands do touch, And palm to palm is holy palmers' kiss. ROMEO Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too? JULIET Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer. ROMEO O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do; They pray, grant thou, lest faith turn to despair. JULIET Saints do not move, though grant for prayers' sake. -

MYTHS Echo and Narcissus Greco/Roman the Greeks

MYTHS Echo and Narcissus Greco/Roman The Greeks (and Romans) were among the early monogamous societies. The men, however, seemed to revel in stories of Zeus’ (Jupiter’s) adulterous escapades with goddesses as well as humans, and enjoyed tales of the jealousies of his wife, Hera (Juno), the goddess of marriage and the family. For the full introduction to this story and for other stories, see The Allyn & Bacon Anthology of Traditional Literature edited by Judith V. Lechner. Allyn & Bacon/Longman, 2003. From: Outline of Mythology: The Age of Fable, The Age of Chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne by Thomas Bulfinch. New York: Review of Reviews Company, 1913. pp. 101-103. Echo was a beautiful nymph, fond of the woods and hills, where she devoted herself to woodland sports. She was a favorite of Diana, and attended her in the chase. But Echo had one failing: she was fond of talking, and whether in chat or argument, would have the last word. One day Juno was seeking her husband, who, she had reason to fear, was amusing himself among the nymphs. Echo by her talk contrived to detain the goddess till the nymphs made their escape. When Juno discovered it, she passed sentence upon Echo in these words: “You shall forfeit the use of that tongue with which you have cheated me, except for the one purpose you are so fond of—reply. You shall still have the last word, but no power to speak the first.” This nymph saw Narcissus, a beautiful youth, as he pursued the chase upon the mountains. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream Education Pack

EDUCATION PACK 1 Contents Introduction Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................3 Section 1: An Introduction to Shakespeare ……………………......................................................................……4 William Shakespeare 1564 - 1616 ..................................................................................................................5 Elizabethan and Jacobean Theatre..................................................................................................................7 Section 2: The Watermill’s Production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream....................................................10 A Brief Synopsis ............................................................................................................................................11 Character Profiles…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….13 Character Map...............................................................................................................................................15 Themes of The Watermill’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream………………………………………………………………………..16 Meet the Cast................................................................................................................................................18 The Design Process........................................................................................................................................21 Costume Designs……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..23 -

Greek Mythology and Medical and Psychiatric Terminology

HISTORY OF PSYCHIATRY Greek mythology and medical and psychiatric terminology Loukas Athanasiadis A great number of terms in modern psychiatry, Narcissus gave his name to narcissism (ex medicine and related disciplines originate from treme self-love based on an idealised self-image). the Greek, including pathology, schizophrenia, He was a young man extremely proud of his ophthalmology, gynaecology, anatomy, pharma beauty and indifferent to the emotions of those cology, biology, hepatology, homeopathy, allo who fell in love with him. A goddess cursed him pathy and many others. There are also many to feel what it is to love and get nothing in return. terms that originate from figures from ancient He subsequently fell in love with his own image Greek mythology (or the Greek words related to when he saw his reflection in the water of a those figures) and I think that it might be fountain, and believed that this image belonged interesting to take a look at some of them. to a spirit. Every time he tried to embrace the Psyche means 'soul' in Greek and she gave her image it disappeared and appeared without names to terms like psychiatry (medicine of the saying a word. At the end the desperate soul), psychology, etc. Psyche was a mortal girl Narcissus died and was turned into a flower that with whom Eros ('love', he gave his name to still bears his name. erotomania, etc.) fell in love. Eros's mother Echo was a very attractive young nymph who Aphrodite had forbidden him to see mortal girls. always wanted to have the last word. -

Answers for the Story of Pyramus and Thisbe

Questions for the Story of Pyramus and Thisbe Instructions: Answer the following questions in complete sentences as you will be sharing this story with your cartography team. 1. What is the problem that Pyramus and Thisbe face from their families? Their families forbid them to be together or see each other. 2. What is the solution they came up with to solve their problem? They decide to meet at night outside the walls of the city so they can be together. 3. What three objects are located in the area where they decide to meet? The three objects that are located in the area where they decide to meet are a tree, a stream, and a cemetery. 4. What incident happens to Thisbe as she is waiting under the tree for Pyramus? Thisbe is attacked by a lioness. 5. What is the name of the item Thisbe dropped on the ground? Thisbe drops her veil as she runs from the lioness. 6. What action does Pyramus perform when he thinks Thisbe is dead? Pyramus falls on his sword and dies when he thinks Thisbe is dead. 7. What continues happen even to today to the white fruit of the mulberry tree as a result of the lovers’ tragedy? The white fruit of the mulberry tree turns a dark purple color when ripe. 8. What proposal would you make to improve Pyramus and Thisbe’s situation? Answers will vary. 9. What other story do the Story of Pyramus and Thisbe resemble? What differences do you notice between these two stories? The Story of Pyramus and Thisbe resembles Romeo and Juliet. -

Romeo and Juliet

Study Guide Romeo and Juliet A Tragedy has 4 Elements Tragic Hero Supernatural Element born Hero has a fatal FLAW Hero’s FATE leads to A mystical, mysterious, Hero is Noble born High downfall or death or unnatural element class occurs during the Influences society Tragic Hero’s life Guide Romeo and Juliet Romeo is a Tragic Hero Romeo Romeo’s FLAW Supernatural is Element Noble Born FATE causes Romeo to NEVER receive the note from Friar Laurence Potion born Romeo is Impulsive mysterious unnatural potion Romeo is born to a Romeo is impulsive … It is FATE that causes Juliet has taken a noble high class family this FLAW causes him to Romeo to NEVER mysterious potion that and is the hero of the make quick decisions receive the note from makes her look dead. play. without thinking. Friar Laurence telling Romeo kills himself him that Juliet plans to because he thinks Juliet FAKE her death. is dead, but she is FAKING death. J. Haugh 2014 X Drive/ English/ Romeo Juliet/ Study Guide Romeo and Juliet 1 Problems or Complications for Juliet Not a Problem of Complication for Juliet There is an ongoing feud between Juliet is NOT in love with Paris so this Capulet and Montague families is not a problem or complication Lady Capulet (Juliet’s mom) wants her to marry Paris Tybalt wants to fight Romeo to the death The feud between the Capulet and Montague Families Obstacles for Romeo Lady Capulet wants Juliet to marry Paris and Juliet Comic Relief happens when a writer puts humor into a serious situation to break the tension Juliet’s Nurse provides COMIC RELIEF in a serious situation J. -

A Pair of Star Crossed Lovers Take Their Life…” Is a Passage from the Prologue

Name: Multiple Choice Act I _____ 1. “A pair of star crossed lovers take their life…” is a passage from the prologue. The term “star- crossed levers” means: a. Romeo and Juliet are destined by fate not to have a happy life b. Romeo compared Juliet’s eyes to stars c. Romeo and Juliet used the stars to find each other d. Their getting together was predicted by the stars _____ 2. Benvolio tries to make peace during the street brawl but is stopped by: a. the Prince b. Tybalt c. someone biting his thumb at him d. Romeo _____ 3. At the beginning of the play, Romeo is sad because: a. Tybalt vowed to kill him b. Rosalyn will not return his love c. Juliet will not return his love d. because of the big fight _____ 4. At the party, a. Tybalt recognizes Romeo b. Lord Capulet tells Tybalt to kill Romeo c. Mercutio gets drunk b. Benvolio falls in love with Juliet Act II _____ 5. Juliet professes her love for Romeo because: a. she is mad at her father b. she is scared that since he is a Montague, he will hate her c. she is unaware that he is in the garden listening d. Romeo tells her he loves her first _____ 6. “Wherefore art thou Romeo?” means: a. Why are you Romeo? b. Who is Romeo? c. Where are you Romeo? d. Yo! What sup? _____ 7. That night they agree to: a. keep their love a secret b. get married c. kill Tybalt d. -

Romeo and Juliet: Sword Fight

Romeo and Juliet: Sword Fight Name: ______________________________ One of the advantages of a play over prose writings, such as a novel, is that the actions in the plot can be seen by the audience. In a novel the author can only describe the action. An example of this is the sword fight between Mercutio and Tybalt in William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. As the scene opens, Mercutio is in the a public square with Benvolio and some servants when Tybalt and his friends arrive. An argument starts, and then the newly-married Romeo arrives. Act III. Scene 1 [Tybalt under Romeo’s arm stabs Mercutio, and flies with his followers.] Mercutio: Tybalt: I am hurt. Romeo, the hate I bear thee can afford A plague o’ both your houses! I am sped. No better term than this,--thou art a villain. Is he gone, and hath nothing? Romeo: Benvolio: Tybalt, the reason that I have to love thee What, art thou hurt? Doth much excuse the appertaining rage Mercutio: To such a greeting: villain am I none; Ay, ay, a scratch, a scratch; marry, ‘tis enough. Therefore farewell; I see thou know’st me not. Where is my page? Go, villain, fetch a surgeon. Tybalt: [Exit Page] Boy, this shall not excuse the injuries Romeo: That thou hast done me; therefore turn and draw. Courage, man; the hurt cannot be much. Romeo: Mercutio: I do protest, I never injured thee, No, ‘tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a But love thee better than thou canst devise, church-door; but ‘tis enough,’twill serve: ask for Till thou shalt know the reason of my love: me to-morrow, and you shall find me a grave man. -

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare Abridged for The

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare Abridged for the Shakespeare Schools Festival by Martin Lamb & Penelope Middelboe 30 MINUTE VERSION © Shakespeare Schools Festival (SSF) “We are such stuff as dreams are made on.” Copyright of the abridged scripts rest with Shakespeare Schools Festival charity. Your registration fee only allows you to perform the abridgement during the current Festival. You may not share the script with other schools, or download all the scripts for personal use. A public performance of the SSF abridged script must be premiered at the professional SSF theatre. 1 LIST OF ROLES Prince Escalus PRINCE OF VERONA Paris A YOUNG COUNT Montague HEAD OF THE HOUSE OF MONTAGUE Capulet HEAD OF THE HOUSE OF CAPULET Romeo MONTAGUE’S SON Mercutio KINSMAN TO THE PRINCE, FRIEND TO ROMEO Benvolio NEPHEW TO MONTAGUE, FRIEND TO ROMEO Tybalt NEPHEW TO LADY CAPULET Juliet DAUGHTER TO CAPULET Nurse to Juliet Lady Montague WIFE TO MONTAGUE Lady Capulet WIFE TO CAPULET Friar Lawrence OF THE FRANCISCAN ORDER, FRIEND TO ROMEO Friar John OF THE FRANCISCAN ORDER Balthazar SERVANT TO ROMEO Sampson SERVANTS TO CAPULET & Gregory Abraham SERVANT TO MONTAGUE An Apothecary Citizens, Revellers And Others 2 PROLOGUE CHORUS Two households both alike in dignity, In fair Verona where we lay our scene From ancient grudge, break to new mutiny, Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean: From forth the fatal loins of these two foes, A pair of star crossed lovers take their life: Whose misadventured piteous overthrows, Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife. SCENE 1 A street ENTER SAMPSON and GREGORY of the house of Capulet, in conversation. -

Romeo and Juliet | Program Notes

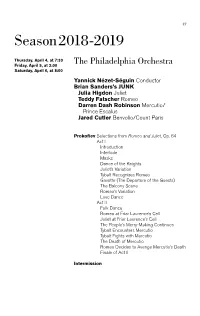

27 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, April 4, at 7:30 Friday, April 5, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, April 6, at 8:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Brian Sanders’s JUNK Julia Higdon Juliet Teddy Fatscher Romeo Darren Dash Robinson Mercutio/ Prince Escalus Jared Cutler Benvolio/Count Paris ProkofievSelections from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64 Act I Introduction Interlude Masks Dance of the Knights Juliet’s Variation Tybalt Recognizes Romeo Gavotte (The Departure of the Guests) The Balcony Scene Romeo’s Variation Love Dance Act II Folk Dance Romeo at Friar Laurence’s Cell Juliet at Friar Laurence’s Cell The People’s Merry-Making Continues Tybalt Encounters Mercutio Tybalt Fights with Mercutio The Death of Mercutio Romeo Decides to Avenge Mercutio’s Death Finale of Act II Intermission 28 Act III Introduction Farewell Before Parting Juliet Refuses to Marry Paris Juliet Alone Interlude At Friar Laurence’s Cell Interlude Juliet Alone Dance of the Girls with Lilies At Juliet’s Bedside Act IV Juliet’s Funeral The Death of Juliet Additional cast: Aaron Mitchell Frank Leone Kyle Yackoski Kelly Trevlyn Amelia Estrada Briannon Holstein Jess Adams This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. These concerts are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. These concerts are made possible, in part, through income from the Allison Vulgamore Legacy Endowment Fund. The April 4 concert is sponsored by Sandra and David Marshall. The April 5 concert is sponsored by Gail Ehrlich in memory of Dr. George E. -

Amphitrite - Wiktionary

Amphitrite - Wiktionary https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Amphitrite Amphitrite Definition from Wiktionary, the free dictionary See also: amphitrite Contents 1 Translingual 1.1 Etymology 1.2 Proper noun 1.2.1 Hypernyms 1.3 External links 2 English 2.1 Etymology 2.2 Pronunciation 2.3 Proper noun 2.3.1 Translations Translingual Etymology New Latin , from Ancient Greek Ἀµφιτρίτη ( Amphitrít ē, “mother of Poseidon”), also "three times around", perhaps for the coiled forms specimens take. Amphitrite , unidentified Amphitrite ornata species Proper noun Amphitrite f 1. A taxonomic genus within the family Terebellidae — spaghetti worms, sea-floor-dwelling polychetes. 1 of 2 10/11/2014 5:32 PM Amphitrite - Wiktionary https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Amphitrite Hypernyms (genus ): Animalia - kingdom; Annelida - phylum; Polychaeta - classis; Palpata - subclass; Canalipalpata - order; Terebellida - suborder; Terebellidae - family; Amphitritinae - subfamily External links Terebellidae on Wikipedia. Amphitritinae on Wikispecies. Amphitrite (Terebellidae) on Wikimedia Commons. English Etymology From Ancient Greek Ἀµφιτρίτη ( Amphitrít ē) Pronunciation Amphitrite astronomical (US ) IPA (key): /ˌæm.fɪˈtɹaɪ.ti/ symbol Proper noun Amphitrite 1. (Greek mythology ) A nymph, the wife of Poseidon. 2. (astronomy ) Short for 29 Amphitrite, a main belt asteroid. Translations ±Greek goddess [show ▼] Retrieved from "http://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=Amphitrite&oldid=28879262" Categories: Translingual terms derived from New Latin Translingual terms derived from Ancient Greek Translingual lemmas Translingual proper nouns mul:Taxonomic names (genus) English terms derived from Ancient Greek English lemmas English proper nouns en:Greek deities en:Astronomy en:Asteroids This page was last modified on 27 August 2014, at 03:08. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.