Analysis of Meghan Trainor 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Husband EZ

Future Husband EZ Count: 32 Wall: 4 Level: Basic Beginner Choreographer: Annemaree Sleeth - October 2014 (Australia) Music: Dear Future Husband by Meghan Trainor. Album: Title E.P . [ (Album: “Title”, 3:04, BPM: 159 – iTunes) No Tags No Restarts Yay! Begin on Lyrics (8 Beats in from Ah! ) 22 seconds in Sec 1 - 1-8: SIDE KICK, SIDE, KICK, SIDE, KICK, SIDE TOUCH (move arms L &R across body) 1-2 Step R side, kick L over R , 3-4 Step L side, kick R over L, 5-6 Step R side, kick L over R, 7-8 Step L side, Touch R tog, Sec 2 - 9-16: V STEP, ¼ V STEP (arms out like swimming breaststroke ) 1-2 Step R dia forward, step L diag forward 3-4 Step R back , step L together 5-6 Turn ¼ R step dia forward, step L diag forward 3.00 7-8 Step R back , step L together Sec 3 - 17- 24: HEEL TOE SWIVELS, HOLD, RIGHT HOLD, HEEL TOE SWIVELS LEFT, HOLD 1-2 Swivel heels R side, swivel R toes R side (add swivels arms on all swivel steps) 3-4 Swivel heels R side, hold (or clap your hands on holds) 5-6 Swivel heels L side, swivel toes L side 7-8 Swivel heels L side, hold (or clap your hands on holds (weight L) Sec 4 - 25 –32: ¼ L, FLICK, ¼ L, FLICK, HIP BUMPS 1-2 Step R fwd 1/4 turn L, Flick L, 12.00 3-4 turn1/4 L step L fwd , Flick R, 5-8 Step R side and Bumps hips R, L ,R , L ( swings hands to the sides) 9.00 Easier Option for Sec 4 Counts 1- 4 Counts 1- 4 Step R, Hold, ½ pivot L, hold : or flick into the hip bumps Ending Wall 14 9.00 to Face Front Dance First 8 Counts & add ¼ R step R side (arms out to each side finish ) Contact - Website: www.inlinedancing.webs.com - Email [email protected] Version 1 October 2014 . -

Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57Th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards

December 10, 2014 Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards Award Nominees Created With the Company's Industry-Leading Music Solutions Include Beyonce's Beyonce, Ed Sheeran's X, and Pharrell Williams' Girl BURLINGTON, Mass., Dec. 10, 2014 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Avid® (Nasdaq:AVID) today congratulated its many customers recognized as award nominees for the 57th Annual GRAMMY® Awards for their outstanding achievements in the recording arts. The world's most prestigious ceremony for music excellence will honor numerous artists, producers and engineers who have embraced Avid EverywhereTM, using the Avid MediaCentral Platform and Avid Artist Suite creative tools for music production. The ceremony will take place on February 8, 2015 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California. Avid audio professionals created Record of the Year and Song of the Year nominees Stay With Me (Darkchild Version) by Sam Smith, Shake It Off by Taylor Swift, and All About That Bass by Meghan Trainor; and Album of the Year nominees Morning Phase by Beck, Beyoncé by Beyoncé, X by Ed Sheeran, In The Lonely Hour by Sam Smith, and Girl by Pharrell Williams. Producer Noah "40" Shebib scored three nominations: Album of the Year and Best Urban Contemporary Album for Beyoncé by Beyoncé, and Best Rap Song for 0 To 100 / The Catch Up by Drake. "This is my first nod for Album Of The Year, and I'm really proud to be among such elite company," he said. "I collaborated with Beyoncé at Jungle City Studios where we created her track Mine using their S5 Fusion. -

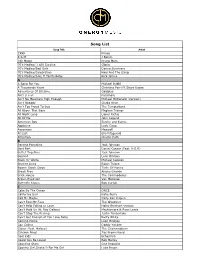

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

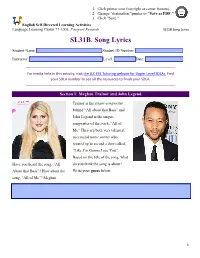

SL31B. Song Lyrics

1. Click printer icon (top right or center bottom). 2. Change "destination"/printer to "Save as PDF." 3. Click "Save." English Self-Directed Learning Activities Language Learning Center 77-1005, Passport Rewards SL31B.Song Lyrics SL31B. Song Lyrics Student Name: _________________________________ Student ID Number: ________________________ Instructor: _____________________________________ Level: ___________Date: ___________________ For media links in this activity, visit the LLC ESL Tutoring website for Upper Level SDLAs. Find your SDLA number to see all the resources to finish your SDLA. Section 1: Meghan Trainor and John Legend Trainor is the singer-songwriter behind “All about that Bass” and John Legend is the singer- songwriter of the track, “All of Me” They are both very talented, successful music artists who teamed up to record a duet called, “Like I’m Gonna Lose You”. Based on the title of the song, what Have you heard the song, “All do you think the song is about? About that Bass”? How about the Write your guess below. song, “All of Me”? Meghan __________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 English Self-Directed Learning Activities Language Learning Center 77-1005, Passport Rewards SL31B.Song Lyrics Section 2: Words to Know In the paragraph in Section 1, some of the underlined words may be unfamiliar to you. Try to match the word on the left to the correct meaning on the right below. Word Meaning A. Singer-songwriter ______ a performance by two people, especially singers, instrumentalists, or dancers B. Track _______ to join another person or group, especially in order to work together to do something C. Duet ______ one of several songs on a musical recording ______ a musician who records and releases music, often professionally, through a D. -

Sample Song List: 1. Uptown Funk

Sample Song List: 1. Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars 2. Live Louder - Nathaniel 3. All About that Bass - Megan Trainor 4. Break Free - Ariana Grande 5. 4, 5 Seconds - Rihanna 6. Locked out of Heaven - Bruno Mars 7. Ghost - Ella Henderson 8. Shake it off - Taylor Swift 9. Trouble - Iggy Azelia 10. Love on Top - Beyonce 11. Happy - Pharell Williams 12. Get Lucky - Daft Punk 13. Highway to Hell - ACDC 14. Shook me all night long - ACDC 15. I Love Rock & Roll - Joan Jett 16. Are you Gonna be my Girl - Jet 17. Blister in the Sun - Violent Femmes 18. April Sun in Cuba - Dragon 19. Better - Screaming Jets 20. (Am I Ever Gonna) See your Face Again - Angels 21. Rain - Dragon 22. Run to Paradise - Choir Boys 23. Teenage Dirtbag - Wheetus 24. Domino - Jessie J 25. Bad Romance - Lady Gaga 26. Summer of '69 - Bryan Adams 27. Sunday Morning - No Doubt 28. Only Girl in the World - Rihanna 29. What's Up - 4 non Blondes 30. Living on a Prayer - Bon Jovi 31. Bed of Roses - Bon Jovi 32. Walking on Sunshine - Katrina and the Waves 33. Groove is in the Heart - Dee Lite 34. Like a Prayer - Madonna 35. Forget You - Cee Lo Green 36. Zombie - Cranberries 37. Boys of Summer - (DJ Sammy Version) 38. Call me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen 39. Wake me up - Avici 40. Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon 41. Funky Music - Wild Cherry 42. Superstition - Stevie Wonder 43. Signed Sealed Delivered - Stevie Wonder 44. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson 45. All the Small Things - Blink 182 46. -

The Justice in Policing Act of 2020 in the U.S

June 23, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House 1236 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Honorable Kevin McCarthy Republican Leader 2468 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: Since the killing of George Floyd just one month ago, our country has seen protests grow, attitudes shift, and calls for change intensify. We in the music and entertainment communities believe that Black lives matter and have long decried the injustices endured by generations of Black citizens. We are more determined than ever to push for federal, state, and local law enforcement programs that truly serve their communities. Accordingly, we are grateful for movement of the Justice in Policing Act of 2020 in the U.S. House of Representatives and urge its quick passage. The Justice in Policing Act is not about marginal change; it takes bold steps that will make a real, positive difference for law enforcement and the communities they serve. We celebrate the long- overdue rejection of qualified immunity, emphasizing that law enforcement officers themselves are not above the law – that bad cops must be held accountable and victims must have recourse. We applaud the provisions to ban chokeholds and no-knock warrants, to establish a national police misconduct registry, to collect data and improve investigations into police misconduct, to promote de-escalation practices, to establish comprehensive training programs, and to update and enhance standards and practices. This legislation will not only promote justice; it will establish a culture of responsibility, fairness, and respect deserving of the badge. Our communities and nation look to you to take a stand in this extraordinary moment and we respectfully ask that you vote YES on the Justice in Policing Act of 2020. -

Rolling in the Deep Al Green

ACDC - Shook Me All Night Long Adele - Rolling In the Deep Al Green - Let’s Stay Together Amy Winehouse - Valerie Ariana Grande - Problem Avicci - Wake me Up Bel Biv Devoe - Poison Beyonce - Crazy In Love Beyonce - Single Ladies Beyonce - Naughty Girl Black Street - No Diggiy Bob Marley - Could You Be Loved Bobby Brown - My Prerogative Bon Jovi - Living On a Prayer Bruno Mars - Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars - Run Away Baby Cee Lo - Forget You Cheap Trick - I Want You To Want Me Chris Brown - Fine China Commodores - Brickhouse Commodores - Easy Cure - Just Like Heaven Daft Punk - Get Lucky Darius Rucker - Wagon Wheel David Bowie - Let’s Dance Disclosure ft. Sam Smith - Latch DJ Cupid - Cupid Shuffle Duffy - Mercy Earth Wind and Fire - Let’s Groove Earth Wind and Fire - September Ed Sheeran - Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran - Sing Estelle - American Boy Etta James - At Last Eurithmics - Sweet Dreams Fontella Bass - Rescue Me Gnarls Barkley - Crazy Hall And Oates - Dreams Come True Janella Monae - Tightrope Jason Derulo - Talk Dirty To Me Journey - Don’t Stop Believing Journey - Anyway You Want It Juanes - Camisa Negra Justin Timberlake - Mirrors Justin Timberlake - Rock Your Body Justin Timberlake - Suit and Tie Katy Perry - Roar Katy Perry - Teenage Dream Ke$ha - Die Young Kool and the Gang - Ladies Night Lady Gaga - Just Dance Lenny Kravitz - Are You Gonna Go My Way Lorde - Royal Louis Armstrong - What A Wonderful World Maddie & Tae - Girl In a Country Song Madonna - Material Girl MAGIC! - Rude Mana - Oye Mi Amor Mark Ronson/Bruno Mars -

All About That Bass’, the Hit Single Written and 70 Million People Had Already Watched—And Shaken Go

THE MONTH IN ART, SOCIETY, PHOTOGRAPHY, BOOKS AND MUSIC in EDITED BY ANINDITA GHOSE INSPIRE All about “I just wish I’d loved myself that bass more growing They’ve been more than just role up. I was so cute” models for those who don’t fit the —MEGHAN TRAINOR mannequin mould. From music to comedy, blogs to books—Vogue meets the ladies sounding the clarion call RAY BROWN RAY / for curvy women everywhere Meghan Trainor, singer Her 2014 body pride anthem ushered a new “era of the booty” ART DEPT. MANICURE: MARY SOUL MARY MANICURE: DEPT. ART / “Yeah it’s pretty clear, I ain’t no size two/ But I can shake it, shake it like I’m supposed to do…” the lyrics go. Before her album released last year, more than 70 million people had already watched—and shaken it to—‘All About That Bass’, the hit single written and UP: TRACY ALFOJARA TRACY UP: - performed by 21-year-old Meghan Trainor. “When I wrote it, the words flew out of my mouth—I had the NOISEMAKING lyrics down in about 45 minutes,” says Trainor. She MOMENT admits to feeling out of place as a teen: “I grew up ‘All About That Bass’ became the in Nantucket, in Massachusetts, and played football longest-running number one hit in school. My crowd was all the skinny, beautiful, in Epic Records’ history, beating popular girls and I was their… thicker friend. This even Michael Jackson’s numbers. one dude I was in love with told me in seventh It spent eight weeks topping grade, ‘You’d be so much hotter if you were 10 pounds lighter.’ It crushed me. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. DANCE STREET BAND SAMPLE SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Adele Rolling in the Deep Rumor Has It Alicia Keys Fallin’ Girl On Fire If I Ain’t Got You Ariana Grande Break Free Problem Side to Side Beyonce Crazy In Love Deja Vu Formation Irreplaceable Love On Top Run the World (Girls) Single Ladies Xo Biz Markie Just a Friend The Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow I Gotta Feeling Imma Be Let’s Get It Started The Time (Dirty Bit) Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Locked Out of Heaven That’s What I Like Treasure Uptown Funk Cardi B Bodak Yellow Carly Rae Jespen Call Me Maybe Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Feel So Close Cee Lo Green Forget You The Chainsmokers Closer Don't Let Me Down Chance the Rapper No Problem Chris Brown Look at Me Now Christina Perri A Thousand Years Christina Aguilera, Lil’Kim, Mya &Pink Lady Marmalade Clean Bandit Rather Be Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky One More Time David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Sorry Not Sorry Desiigner Panda DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake Hold on We're Going Home Hotline Bling One Dance Echosmith Cool Kids Ed Sheeran Perfect Shape of You Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low Fun. -

Songs We Secretly Sing in the Car!

Songs We Secretly Sing in the Car! Produced by Alfred Music P.O. Box 10003 Van Nuys, CA 91410-0003 alfred.com Printed in USA. No part of this book shall be reproduced, arranged, adapted, recorded, publicly performed, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without written permission from the publisher. In order to comply with copyright laws, please apply for such written permission and/or license by contacting the publisher at alfred.com/permissions. ISBN-10: 1-4706-2741-8 ISBN-13: 978-1-4706-2741-6 2 Contents Title Artist Afternoon Delight ..............................................................Starland Vocal Band ..............................6 All About That Bass .............................................................Meghan Trainor .................................. 10 Build Me Up Buttercup .......................................................The Foundations ................................. 13 Cara Mia.............................................................................Jay & the Americans ............................ 16 Dancing Queen ..................................................................ABBA .................................................. 18 Delta Dawn ........................................................................Helen Reddy ....................................... 21 Disco Inferno ......................................................................The Trammps ...................................... 28 Don’t Stop Believin’ ............................................................Journey -

Host Neil Patrick Harris, Alongside Mahershala Ali, Chance The

Host Neil Patrick Harris, alongside Mahershala Ali, Chance The Rapper, Selena Gomez, Natalie Portman, Hailee Steinfeld, Meghan Trainor and more unite at WE Day California to celebrate youth leading lasting social change in America – Click here to apply for media accreditation to attend WE Day California – – WE Day California is free to thousands of students thanks to partners led by National Co-Title Sponsor The Allstate Foundation and Co-Title Sponsor Unilever – Inglewood, CA (April 11, 2019) – Today, WE Day, the greatest celebration of social good, announces the dynamic lineup set to hit the stage at WE Day California, taking place at the “Fabulous” Forum on April 25, 2019. With stadium sized events across North America, the UK and the Caribbean, WE Day returns to California uniting 16,000 extraordinary students and educators who have made a difference in their local and global communities. Together they will enjoy a day of unforgettable performances and motivational speeches with WE co-founders and international activists Craig Kielburger and Marc Kielburger, host Neil Patrick Harris, Mahershala Ali, Chance The Rapper, Selena Gomez, Joe Jonas, Bill Nye, Pentatonix, Natalie Portman, Hailee Steinfeld, Meghan Trainor, will.i.am and more, still to be announced. WE Day is free of charge to students and educators across the U.S. thanks to the generous support of sponsors, led by National Co-Title Sponsor The Allstate Foundation and Co-Title Sponsor Unilever. “Every year, WE Day leaves me feeling inspired and hopeful. The youth have an incredible positive and passionate attitude for making real change in the world” says actress and multi-platinum recording artist, Selena Gomez.