Secrets of the Past in a Rugged Land: the Archaeological Case For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saline Soils and Water Quality in the Colorado River Basin: Natural and Anthropogenic Causes Gabriel Lahue River Ecogeomorphology Winter 2017

Saline soils and water quality in the Colorado River Basin: Natural and anthropogenic causes Gabriel LaHue River Ecogeomorphology Winter 2017 Outline I. Introduction II. Natural sources of salinity and the geology of the Colorado River Basin IIIA. Anthropogenic contributions to salinity – Agriculture IIIB. Anthropogenic contributions to salinity – Other anthropogenic sources IV. Moving forward – Efforts to decrease salinity V. Summary and conclusions Abstract Salinity is arguably the biggest water quality challenge facing the Colorado River, with estimated damages up to $750 million. The salinity of the river has doubled from pre-dam levels, mostly due to irrigation and reservoir evaporation. Natural salinity sources – saline springs, eroding salt-laden geologic formations, and runoff – still account for about half of the salt loading to the river. Consumptive water use for agricultural irrigation concentrates the naturally- occurring salts in the Colorado River water, these salts are leached from the root zone to maintain crop productivity, and the salts reenter the river as agricultural drainage water. Reservoir evaporation represents a much smaller cause of river salinity and most programs to reduce the salinity of the Colorado River have focused on agriculture; these include the lining of irrigation canals, irrigation efficiency improvements, and removing areas with poor drainage from production. Salt loading to the Colorado River has been reduced because of these efforts, but more work will be required to meet salinity reduction targets. Introduction The Colorado River is one of the most important rivers in the Western United States: it provides water for approximately 40 million people and irrigation water for 5.5 million acres of land, both inside and outside the Colorado River Basin (CRBSCF, 2014). -

West Colorado River Plan

Section 9 - West Colorado River Basin Water Planning and Development 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Background 9-1 9.3 Water Resources Problems 9-7 9.4 Water Resources Demands and Needs 9-7 9.5 Water Development and Management Alternatives 9-13 9.6 Projected Water Depletions 9-18 9.7 Policy Issues and Recommendations 9-19 Figures 9-1 Price-San Rafael Salinity Control Project Map 9-6 9-2 Wilderness Lands 9-11 9-3 Potential Reservoir Sites 9-16 9-4 Gunnison Butte Mutual Irrigation Project 9-20 9-5 Bryce Valley 9-22 Tables 9-1 Board of Water Resources Development Projects 9-3 9-2 Salinity Control Project Approved Costs 9-7 9-3 Wilderness Lands 9-8 9-4 Current and Projected Culinary Water Use 9-12 9-5 Current and Projected Secondary Water Use 9-12 9-6 Current and Projected Agricultural Water Use 9-13 9-7 Summary of Current and Projected Water Demands 9-14 9-8 Historical Reservoir Site Investigations 9-17 Section 9 West Colorado River Basin - Utah State Water Plan Water Planning and Development 9.1 Introduction The coordination and cooperation of all This section describes the major existing water development projects and proposed water planning water-related government agencies, and development activities in the West Colorado local organizations and individual River Basin. The existing water supplies are vital to water users will be required as the the existence of the local communities while also basin tries to meet its future water providing aesthetic and environmental values. -

Floating the Dirty Devil River

The best water levels and time Wilderness Study Areas (WSA) of year to float the Dirty Devil The Dirty Devil River corridor travels through two The biggest dilemma one faces when planning BLM Wilderness Study Areas, the Dirty Devil KNOW a float trip down the Dirty Devil is timing a WSA and the Fiddler Butte WSA. These WSA’s trip when flows are sufficient for floating. On have been designated as such to preserve their wil- BEFORE average, March and April are the only months derness characteristics including naturalness, soli- YOU GO: that the river is potentially floatable. Most tude, and primitive recreation. Please recreate in a people do it in May or June because of warm- manner that retains these characteristics. Floating the ing temperatures. It is recommended to use a hard walled or inflatable kayak when flows Dirty Devil are 100 cfs or higher. It can be done with “Leave-no-Trace” River flows as low as 65 cfs if you are willing to Proper outdoor ethics are expected of all visitors. drag your boat for the first few days. Motor- These include using a portable toilet when camping ized crafts are not allowed on this stretch of near a vehicle, using designated campgrounds The name "Dirty Devil" tells it river. when available, removing or burying human waste all. John Wesley Powell passed in the back country, carrying out toilet paper, using by the mouth of this stream on Another essential consideration for all visitors camp stoves in the backcountry, never cutting or his historic exploration of the is flash flood potential. -

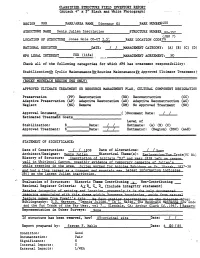

Denis Julien Inscription ____ STRUCTURE NUMBER (JHO 7) LOCATION of STRUCTURE Jones Hole CO-UT 7.5' PARK LOCATION CODEPG

REGION RMR PARK/AREA NAME Dinosaur Nil_______PARK NUMBEIJ^QO STRUCTURE NAME Denis Julien Inscription ____ STRUCTURE NUMBER (JHO 7) LOCATION OF STRUCTURE Jones Hole CO-UT 7.5' PARK LOCATION CODEPG NATIONAL REGISTER____________DATE: / / MANAGEMENT CATEGORY: (A) (B) (C) (D) NPS LEGAL INTEREST_____FER (life) ^ ______MANAGEMENT AGREEMENT; NO________ Check all of the following categories for which tfPS has treatment responsibility: Stabilization^ Cyclic Maintenance ®X Routine Maintenance &k Approved Ultimate Treatment C (ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION USE ONLY) APPROVED ULTIMATE TREATMENT OR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN, CULTURAL COMPONENT DESIGNATION Preservation (PP) Restoration (RR) Reconstruction (CC) Adaptive Preservation (AP) Adaptive Restoration (AR) Adaptive Reconstruction (AC) Neglect (NG) Remove (RM) No Approved Treatment (NO) Approval Document,______________________m( )Document Date: / / Estimated Treatment Costs Level of Stabilization: $________Date: / / Estimate: (A) (B) (C) Approved Treatment: $________Date: / / Estimator: (Region) (DSC) (A&E) STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE: Date of Construction: / / 1838 Date of Alterations: / / Nnng Architect/Designer: Denis Julien____Historical Theme(s): EyplnraMnn/Fn-r TT-«<WVT 34) History Of Structure: Inscription of initials "PJ" and year 1838 left; on ranynn wall in Whirlpool Canyon, possibly evidence of temporary campsite of Jullen's___ while trapping in the area. Julian worked for Antnlne Rob-:^rmy at- Ft- TT-?nfaV. T and had a long career as a fcrarmey and mrmnfflin man. Latest information indicates 1841 as the latest Julien inscription._________________________________ Evaluation of Structure: Historic Theme Contributing -v . - Non-Contributing __ National Register Criteria: A^B— C_ D_ (Include integrity statement) j.ntegyif'y of agt*fr*fng anH 1or> flt"inr> p-roconf-ly -f •h -^<^ f-Vio ^•^']^Tr j^g'j feature names from PoweH'a rrtp——Ha falti aimilar inooriptiona on tha Colorado raver Bibliography: P.P. -

Preliminary Report on Some Uranium Deposits Along the West Side of the San Rafael Swell, Emery County, Utah

UNITED STATES ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION RMO-673 PRELIMINARY REPORT ON SOME URANIUM DEPOSITS ALONG THE WEST SIDE OF THE SAN RAFAEL SWELL, EMERY COUNTY, UTAH By Millard L. Reyner October 1950 SI-7c1 Division of Raw Materials Exploration Branch Technical Information Service, Oak Ridge, T•nn•ss•• ; "N_ ' \ - —rrs1 • „ 6 NOV 1952 METALLURGY AND CERAMICS Reproduced direct from copy a3 submitted to this office. AEC,Oak Ridge,Tenn.,8-13-51--515-W5593 CONTMITS Page Introduction 1 Geography 3 History 4 Regional geology 4 Economic geology 5 General 5 Mineralogy 7 Deposits examined 8 Lone Tree group. 8 Hard Pan group 11 Dalton group 12 Dexter group 12 Clifford Smith claim 16 Wickiup group 17 Gardell Snow's claim 20 Dolly group 20 South Fork group 20 Hertz No. 1 claim 21 Pay Day claim. Green Vein group. and Brown Throne group 21 Dirty Devil group 26 Summary and conclusions 30 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Index Map of Utah showing location of area examined. • •••••••• OOOOO ••. 2 Figure 2. Map showing locations of uranium prospects and samples on a mesa 4 miles southwest of the San Rafael River bridge. OOOOO . 9 Figure 3. Sketch showing plan, sections, and samples of the Lone Tree adit .••••• OOOOO 10 Figure 4. Plan and sections of Dalton Group showing sample locations and assays . 13 Figure 5. Plan of adit on Dexter Group showing sample looations and assays. 15 Figure 6. Sketch of Block Mountain showing locations of samples in Wickiup Group•• OOOOOO 18 Figure 7. Sketch showing sample locations and assays in main workings of Wickiup Group on the west side of Block Mountain. -

Historical Grazing on the Ashley National Forest

HISTORICAL GRAZING ON THE ASHLEY NATIONAL FOREST A Research Contract between the USDA, Forest Service, Intermountain Region, and the University of Utah’s American West Center FS Agreement No. 10-CS-11046000-035 Report and Database by Michael L. Shamo Co-Principal Investigators: Dr. Matthew Basso and Dr. Paul Reeve August 15, 2012 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Note on Sources 3 An Overview of the Region’s History and Geography 6 Early History 9 The Ashley Valley 14 The Uinta Basin 24 Daggett County 35 The Ashley National Forest 44 Appendix A: Positive Results Appendix B: Negative Results Appendix C: Contextual Results Appendix D: Utah Brand Books INTRODUCTION In August 2010, the Forest Service contracted with the University of Utah’s American West Center to research the early settlement history and use of livestock on lands that are now in or adjacent to the boundaries of the Ashley National Forest. The purpose of the report that follows is to provide documentation supporting the earliest historic use of water for livestock, as well as to deepen understanding of early settlement and grazing in Utah. As this project began, the Ashley National Forest had only partial documentation about grazing on forest lands prior to 1905 (the year Congress transferred control of the nation’s forest reserves to the newly created Forest Service). In 1903 water rights in Utah were required by statute. The various forest reserves that would ultimately combine to form the Ashley were also created around the same time. The area that now comprises the Ashley National Forest began as the Uintah Forest Reserve in 1897. -

Quantifying the Base Flow of the Colorado River: Its Importance in Sustaining Perennial Flow in Northern Arizona And

1 * This paper is under review for publication in Hydrogeology Journal as well as a chapter in my soon to be published 2 master’s thesis. 3 4 Quantifying the base flow of the Colorado River: its importance in sustaining perennial flow in northern Arizona and 5 southern Utah 6 7 Riley K. Swanson1* 8 Abraham E. Springer1 9 David K. Kreamer2 10 Benjamin W. Tobin3 11 Denielle M. Perry1 12 13 1. School of Earth and Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, US 14 email: [email protected] 15 2. Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, US 16 3. Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, US 17 *corresponding author 18 19 Abstract 20 Water in the Colorado River is known to be a highly over-allocated resource, yet decision makers fail to consider, in 21 their management efforts, one of the most important contributions to the existing water in the river, groundwater. This 22 failure may result from the contrasting results of base flow studies conducted on the amount of streamflow into the 23 Colorado River sourced from groundwater. Some studies rule out the significance of groundwater contribution, while 24 other studies show groundwater contributing the majority flow to the river. This study uses new and extant 1 25 instrumented data (not indirect methods) to quantify the base flow contribution to surface flow and highlight the 26 overlooked, substantial portion of groundwater. Ten remote sub-basins of the Colorado Plateau in southern Utah and 27 northern Arizona were examined in detail. -

Projecting Temperature in Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon Dam Tailrace

Projecting Temperature in Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon Dam Tailrace By Nicholas T. Williams1 Abstract factors affecting the magnitude of warming in dam discharges (Bureau of Reclamation, 2007). During the period of warmest river temperatures, the Recent drought in the Colorado River Basin reduced dissolved oxygen content of discharges from the dam declined water levels in Lake Powell nearly 150 feet between 1999 to concentrations lower than any previously observed (fig. 1). and 2005. This resulted in warmer discharges from Glen Operations at Glen Canyon Dam were modified by running Canyon Dam than have been observed since initial filling of turbines at varying speeds, which artificially increased the dis- Lake Powell. Water quality of the discharge also varied from solved oxygen content of discharges; however, these changes historical observations as concentrations of dissolved oxygen also resulted in decreased power generation and possibly dropped to levels previously unobserved. These changes damaged the turbines (Bureau of Reclamation, 2005). The generated a need, from operational and biological resource processes in the reservoir creating the low dissolved oxygen standpoints, to provide projections of discharge temperature content in the reservoir had been observed in previous years, and water quality throughout the year for Lake Powell and but before 2005 the processes had never affected the river Glen Canyon Dam. Projections of temperature during the year below the dam to this magnitude (Vernieu and others, 2005). 2008 were done using a two-dimensional hydrodynamic and As with the warmer temperatures, the low dissolved oxygen water-quality model of Lake Powell. The projections were concentrations could not be explained solely by the reduced based on the hydrological forecast for the Colorado River reservoir elevations. -

Utah History Encyclopedia

ARCHES NATIONAL PARK Double Arch Although there are arches and natural bridges found all over the world, these natural phenomena nowhere are found in such profusion as they are in Arches National Park, located in Grand County, Utah, north of the town of Moab. The Colorado River forms the southern boundary of the park, and the LaSal Mountains are visible from most viewpoints inside the park`s boundaries. The park is situated in the middle of the Colorado Plateau, a vast area of deep canyons and prominent mountain ranges that also includes Canyonlands National Park, Colorado National Monument, Natural Bridges National Monument, and Dinosaur National Monument. The Colorado Plateau is covered with layers of Jurassic-era sandstones; the type most prevalent within the Park is called Entrada Sandstone, a type that lends itself to the arch cutting that gives the park its name. Arches National Park covers more than 73,000 acres, or about 114 square miles. There are more than 500 arches found inside the park′s boundaries, and the possibility exists that even more may be discovered. The concentration of arches within the park is the result of the angular topography, much exposed bare rock, and erosion on a major scale. In such an arid area - annual precipitation is about 8.5 inches per year - it is not surprising that the agent of most erosion is wind and frost. Flora and fauna in the park and its immediate surrounding area are mainly desert adaptations, except in the canyon bottoms and along the Colorado River, where a riverine or riparian environment is found. -

Archeology of the Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National Monument, Georgia

1.2.^5^-3 rK 'rm ' ^ -*m *~ ^-mt\^ -» V-* ^JT T ^T A . ESEARCH SERIES NUMBER THREE Clemson Universii akCHEOLOGY of the FUNERAL MOUND OCMULGEE NATIONAL MONUMENT, GEORGIA TIONAL PARK SERVICE • U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 3ERAL JCATK5N r -v-^tfS i> &, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary National Park Service Conrad L. Wirth, Director Ihis publication is one of a series of research studies devoted to specialized topics which have been explored in con- nection with the various areas in the National Park System. It is printed at the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. Price $1 (paper cover) ARCHEOLOGY OF THE FUNERAL MOUND OCMULGEE National Monument, Georgia By Charles H. Fairbanks with introduction by Frank M. Settler ARCHEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER THREE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U. S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • WASHINGTON 1956 THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM, of which Ocmulgee National Monument is a unit, is dedi- cated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and his- toric heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Foreword Ocmulgee National Monument stands as a memorial to a way of life practiced in the Southeast over a span of 10,000 years, beginning with the Paleo-Indian hunters and ending with the modern Creeks of the 19th century. Here modern exhibits in the monument museum will enable you to view the panorama of aboriginal development, and here you can enter the restoration of an actual earth lodge and stand where forgotten ceremonies of a great tribe were held. -

Establishing the Geomorphic Context for Wetland and Riverine Restoration of the San Rafael River

Final Report Establishing the geomorphic context for wetland and riverine restoration of the San Rafael River NRCS Cooperative Agreement #68-3A75-4-155 Stephen T. Fortney, John C. Schmidt, and David J. Dean Intermountain Center for River Rehabilitation and Restoration Department of Watershed Sciences Utah State University Logan, UT In collaboration with Michael E. Scott Julian Scott Fort Collins Science Center U. S. Geological Survey Fort Collins, CO March 22, 2011 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 5 II. Purpose 5 III. Study Area 9 IV. Hydrology 11 V. Methods 18 A. Floodplain Stratigraphy 18 B. Repeat Photography: Aerial Imagery and Oblique Ground Photographs 19 C. USGS gage data 21 Reconstructed Cross Sections 21 Rating Relations 22 Time Series of Thalweg Elevation 22 Time Series of Width and Width-to-Depth Ratio 22 Hydraulic Geometry 22 D. Longitudinal Profile 24 E. Additional Activities 24 VI. Results: Channel Transformation on Hatt Ranch 26 Turn of the 20th century 26 1930s and 1940s 29 1950s 33 1960s and 1970s 41 1980s 46 1990s to present 49 Longitudinal Profile 50 VII. Summary 54 A. Channel Transformation on Hatt Ranch 54 B. Restoration and Management Implications 55 VIII. Expenditures 56 IX. Timeline 56 X. References 56 XI. Appendix 59 Table of Figures Figure 1. Oblique ground photos taken near the old Highway 24 bridge 6 Figure 2. Conceptual model of how watershed attributes control channel and floodplain form. 7 Figure 3. Conceptual model of restoration versus rehabilitation 8 Figure 4. Map of the San Rafael River watershed. 10 Figure 5. Map of the study area 11 Figure 6. -

Pinworm Infection at Salmon Ruins and Aztec Ruins: Relation to Pueblo III Regional Violence

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 12-2019 Pinworm Infection at Salmon Ruins and Aztec Ruins: Relation to Pueblo III Regional Violence Karl Reinhard Morgana Camacho Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Other Public Health Commons, and the Parasitology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/ Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ISSN (Print) 0023-4001 ISSN (Online) 1738-0006 Korean J Parasitol Vol. 57, No. 6: 627-633, December 2019 ▣ BRIEF COMMUNICATION https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2019.57.6.627 Pinworm Infection at Salmon Ruins and Aztec Ruins: Relation to Pueblo III Regional Violence 1 2, Karl J Reinhard , Morgana Camacho * 1School of Natural Resource Sciences, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA; 2Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abstract: The study of coprolites has been a theme of archaeology in the American Southwest. A feature of archaeopar- asitology on the Colorado Plateau is the ubiquity of pinworm infection. As a crowd parasite, this ubiquity signals varying concentrations of populations. Our recent analysis of coprolite deposits from 2 sites revealed the highest prevalence of infection ever recorded for the region. For Salmon Ruins, the deposits date from AD 1140 to 1280.