Alapakkam : a Resurvey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 1 Angambakkam 2 Ariaperumbakkam 3 Arpakkam 4 Asoor 5 Avalur 6 Ayyengarkulam 7 Damal 8 Elayanarvelur 9 Kalakattoor 10 Kalur 11 Kambarajapuram 12 Karuppadithattadai 13 Kavanthandalam 14 Keelambi 15 Kilar 16 Keelkadirpur 17 Keelperamanallur 18 Kolivakkam 19 Konerikuppam 20 Kuram 21 Magaral 22 Melkadirpur 23 Melottivakkam 24 Musaravakkam 25 Muthavedu 26 Muttavakkam 27 Narapakkam 28 Nathapettai 29 Olakkolapattu 30 Orikkai 31 Perumbakkam 32 Punjarasanthangal 33 Putheri 34 Sirukaveripakkam 35 Sirunaiperugal 36 Thammanur 37 Thenambakkam 38 Thimmasamudram 39 Thilruparuthikundram 40 Thirupukuzhi List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 41 Valathottam 42 Vippedu 43 Vishar 2 Walajabad 1 Agaram 2 Alapakkam 3 Ariyambakkam 4 Athivakkam 5 Attuputhur 6 Aymicheri 7 Ayyampettai 8 Devariyambakkam 9 Ekanampettai 10 Enadur 11 Govindavadi 12 Illuppapattu 13 Injambakkam 14 Kaliyanoor 15 Karai 16 Karur 17 Kattavakkam 18 Keelottivakkam 19 Kithiripettai 20 Kottavakkam 21 Kunnavakkam 22 Kuthirambakkam 23 Marutham 24 Muthyalpettai 25 Nathanallur 26 Nayakkenpettai 27 Nayakkenkuppam 28 Olaiyur 29 Paduneli 30 Palaiyaseevaram 31 Paranthur 32 Podavur 33 Poosivakkam 34 Pullalur 35 Puliyambakkam 36 Purisai List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 37 -

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

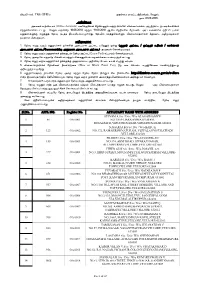

Sl.No. APPL NO. Register No. APPLICANT NAME WITH

tpLtp vz;/ 7166 -2018-v Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;wk;. ntYhh;. ehs; 01/08/2018 mwptpf;if mytyf cjtpahsh; (Office Assistant) gzpfSf;fhd fPH;f;fhqk; kDjhuh;fspd; tpz;zg;g';fs; mLj;jfl;l eltof;iff;fhf Vw;Wf;bfhs;sg;gl;lJ/ nkYk; tUfpd;w 18/08/2018 kw;Wk; 19/08/2018 Mfpa njjpfspy; fPH;f;fz;l ml;ltizapy; Fwpg;gpl;Ls;s kDjhuh;fSf;F vGj;Jj; njh;t[ elj;j jpl;lkplg;gl;Ls;sJ/ njh;tpy; fye;Jbfhs;Sk; tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs; fPH;fz;l tHpKiwfis jtwhky; gpd;gw;wt[k;/ tHpKiwfs; 1/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fspd; milahs ml;il VnjDk; xd;W (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il-ntiytha;g;g[ mYtyf milahs ml;il) jtwhky; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 2/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSld; njh;t[ ml;il(Exam Pad) fl;lhak; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 3/ njh;t[ miwapy; ve;jtpj kpd;dpay; kw;Wk; kpd;dDtpay; rhjd’;fis gad;gLj;jf; TlhJ/ 4/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSf;F mDg;gg;gl;l mwptpg;g[ rPl;il cld; vLj;J tut[k;/ 5/ tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs;; njh;tpid ePyk;-fUik (Blue or Black Point Pen) epw ik bfhz;l vGJnfhiy gad;gLj;JkhW mwpt[Wj;jg;gLfpwJ/ 6/ kDjhuh;fSf;F j’;fspd; njh;t[ miw kw;Wk; njh;t[ neuk; ,d;Dk; rpy jpd’;fspy; http://districts.ecourts.gov.in/vellore vd;w ,izajsj;jpy; bjhptpf;fg;gLk;/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; Kd;dnu midj;J tptu’;fisa[k; mwpe;J tu ntz;Lk;/ 7/ fhyjhkjkhf tUk; ve;j kDjhuUk; njh;t[ vGj mDkjpf;fg;glkhl;lhJ/ 8/ njh;t[ vGJk; ve;j xU tpz;zg;gjhuUk; kw;wth; tpilj;jhis ghh;j;J vGjf; TlhJ. -

Chief Educational Office, Vellore Rte 25% Reservation - 2019-2020 Provisionaly Selected Students List

CHIEF EDUCATIONAL OFFICE, VELLORE RTE 25% RESERVATION - 2019-2020 PROVISIONALY SELECTED STUDENTS LIST Block School_Name Student_Name Register_No Student_Category Address Disadvantage MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO 47 SMALL STREET KAVANUR VILLAGE Arakkonam Adlin S 5363109644 Group_Christian_Scheduled ARAKKONAM AND POST-631004-Vellore Dt Caste MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO 46, SMALL STREET, KAVANOOR, Arakkonam Dhanu K 5346318086 Weaker Section ARAKKONAM ARAKKONAM - 631004-631004-Vellore Dt Disadvantage No. 190/3, School Street, MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Jency V 6409596936 Group_Hindu_Backward Kavanur Village & Post, ARAKKONAM Community Arakkonam-631004-Vellore Dt NO.24 , NAMMANERI VILLAGE, MOSUR MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Joseph J 5589617238 Weaker Section POST, ARAKKONAM TK, VELLORE-631004- ARAKKONAM Vellore Dt Disadvantage 72 ADIDRAVIDAR COLONY ,BIG MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Leonajas E 3636068448 Group_Christian_Backward STREET,KAVANUR ,VELLORE-631004-Vellore ARAKKONAM Community Dt NO 150 3RD CROSS STREET MARY'S VISION MHSS, Arakkonam Rohitha J 7715781823 Weaker Section PULIYAMANGALAM VELLORE-631004- ARAKKONAM Vellore Dt MARY'S VISION MHSS, NO.12, SILVERPET, EKHUNAGAR POST, Arakkonam Varun Kumar 8714376252 Weaker Section ARAKKONAM ARAKKONAM-631004-Vellore Dt NO 78/42 PERUMAL KOVIL STREET CHINNA MARY'S VISION MHSS, Disadvantage MOSUR COLONY MOSUR POST Arakkonam Yazhini R 7091288559 ARAKKONAM Group_Hindu_Scheduled Caste ARAKKONAM TALUK 631004-631004-Vellore Dt 27, METTU COLONY, ROYAL MATRIC HSS, Disadvantage Arakkonam Ashwathi R 6260258005 -

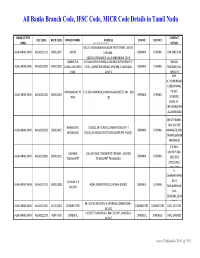

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2015 [Price: Rs. 2.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 197] CHENNAI, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2015 Purattasi 4, Manmadha, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2046 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIES DEPARTMENT THE SCHEDULE ACQUISITION OF LANDS Vellore District, Arakkonam Taluk, 54, Nedumpuli Village, [G.O. Ms. No. 228, Industries (SIPCOT-LA.), 21st September 2015, ¹ó†ì£C 4, ñ¡ñî, F¼õœÀõ˜ Unit-II , Block – IV. ݇´-2046.] Dry – S.No. 370/1 – Name of the Land Owners/Persons No. II(2)/IND/537(a-1)/2015. Interested - Padmanaban S/o Narayanan—1.41.5 Hectares. The Government of Tamil Nadu having been satisfied that Dry – S.No. 370/2A – Name of the Land Owners/Persons the lands specified in the schedule below have to be acquired Interested - Padmanaban S/o Narayanan—0.50.5 Hectares. for industrial purpose to wit for setting up of SIPCOT Dry – S.No. 370/2B – Name of the Land Owners/Persons Panapakkam Industrial Park Scheme Arakkonam and Interested - Arul S/o Venkatesa Mudaliyar—0.79.0 Hectares. surrounding areas and it having already been decided that the entire amount of compensation to be awarded for the Dry – S.No. 370/3A – Name of the Land Owners/Persons lands is to be paid out of the funds controlled or managed Interested - Subramaniya Mudali S/o Rangantha Mudaliyar— by the Government the following Notice is issued under 0.18.5 Hectares. -

Vellore Taluk

VELLORE TALUK Sl. Vulner Name of the Vulnerable Area Relief Centre No ability Local Body URBAN 1.Saravanabhava Kalyana Vellore Mandapam Shenbakkam, 1 Thidir Nagar Low Corporation 2.Government Higher Secondary School Konavattam 1.Saravanabhava Kalyana Vellore Mandapam Shenbakkam, 2 Kansalpet Low Corporation 2.Government Higher Secondary School Konavattam Indira Nagar, 1.Saravanabhava Kalyana Puliyanthoppe, Vellore Mandapam Shenbakkam, 3 Low Rangasamy Nagar, Corporation 2.Government Higher Vasanthapuram Secondary School Konavattam Sambath Nagar Police Kalyana Mandapam, Vellore 4 (Navaneetham Koil Low Kottai Round, Vellore Corporation street) RURAL Magaleer kuzhu kattidam Kaniyambadi 5. Edaiyansathu Low mooppanar nagar Block Edayansathu Kaniyambadi Govt.Higher Secondary 6. Nelvoy Eri Low Block School, Nelvoy Kaniyambadi Panchayat Union Elementary 7. Kilvallam AD Colony Low Block School Vallam Kaniyambadi Panchayat Union Elementary 8. Kilpallipattu Low Block School, Kilpallipattu Kaniyambadi AD Kaniyambadi Panchayat Union Elementary 9. Low Colony Block School, Kaniyambadi ANAICUT TALUK Sl. Vulner Name of the Vulnerable Area Relief Centre No ability Local Body URBAN Pallikonda Town 1.Little Flower Convent 1 Pallikonda Low Panchayat 2. Muthu Kalyana Mandapam RURAL Kasthuri Thirumana Mandapam 2. Ganganallur Low Anaicut Block Genganallur 3. Bramanamangalam Low Anaicut Block G.V.Mahal, Bramanamangalam Panchayat Union Elementary 4. Govinthampadi Canal Low Anaicut Block School, Govindambadi 5. Peiyaru Low Anaicut Block Government School, Karadigudi KATPADI TALUK Sl. Vulner Name of the Vulnerable Area Relief Centre No ability Local Body URBAN Vellore 1. Govt. Ele. School, Kalinjur 1 Kazhinjur Medium Corporation Ward 2. BMD Jain School No.1 RURAL 1. Government High School, 2. Ponnai Medium Sholinghur Block Ponnai, 2.Government Hospital, Ponnai 1.Government Elementary School Melur 2.Government Boys Higher K.V.Kuppam Secondary School, Melur 3. -

LIST of KUDIMARAMATH WORKS 2019-20 WATER BODIES RESTORATION with PARTICIPATORY APPROACH Annexure to G.O(Ms)No.58, Public Works (W2) Department, Dated 13.06.2019

GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT WATER RESOURCES ORGANISATION ANNEXURE TO G.O(Ms.)NO. 58 PUBLIC WORKS (W2) DEPARTMENT, DATED 13.06.2019 LIST OF KUDIMARAMATH WORKS 2019-20 WATER BODIES RESTORATION WITH PARTICIPATORY APPROACH Annexure to G.O(Ms)No.58, Public Works (W2) Department, Dated 13.06.2019 Kudimaramath Scheme 2019-20 Water Bodies Restoration with Participatory Approach General Abstract Total Amount Sl.No Region No.of Works Page No (Rs. In Lakhs) 1 Chennai 277 9300.00 1 - 26 2 Trichy 543 10988.40 27 - 82 3 Madurai 681 23000.00 83 - 132 4 Coimbatore 328 6680.40 133 - 181 Total 1829 49968.80 KUDIMARAMATH SCHEME 2019-2020 CHENNAI REGION - ABSTRACT Estimate Sl. Amount No Name of District No. of Works Rs. in Lakhs 1 Thiruvallur 30 1017.00 2 Kancheepuram 38 1522.00 3 Dharmapuri 10 497.00 4 Tiruvannamalai 37 1607.00 5 Villupuram 73 2642.00 6 Cuddalore 36 815.00 7 Vellore 53 1200.00 Total 277 9300.00 1 KUDIMARAMATH SCHEME 2019-2020 CHENNAI REGION Estimate Sl. District Amount Ayacut Tank Unique No wise Name of work Constituency Rs. in Lakhs (in Ha) Code Sl.No. THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction of sluice 1 1 and desilting the supply channel in Neidavoyal Periya eri Tank in 28.00 Ponneri 354.51 TNCH-02-T0210 ponneri Taluk of Thiruvallur District Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction of sluice 2 2 and desilting the supply channel in Voyalur Mamanikkal Tank in 44.00 Ponneri 386.89 TNCH-02-T0187 ponneri Taluk of Thiruvallur District Restoration by Removal of shoals and Reconstruction -

Downloaded and Incorporated

*OFFICIAL USE ONLY CHENNAI METRO RAIL LIMITED CHENNAI 600017 INDIA Specific Procurement Notice (SPN) SPN No: CMRL/PHASE II/CORRIDOR 4/C4-ECV-01 International Open Competitive Tender Country : INDIA Employer : Chennai Metro Rail Limited Project : Chennai Metro Rail Phase 2 Corridor 4 Loan No. : AIIB / [Loan under process] Contract Title : “Construction of Elevated Metro Stations at Power House, Vadapalani, Saligramam, Avichi School, Alwartiru Nagar, Valasaravakkam, Karambakkam, Alapakkam Junction, Porur Junction & Associated Viaduct From Chainage 10027.102 To Chainage.17982.240 and all Associated works” 1. The Government of India has applied for financing from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) toward the cost of construction of the Chennai Metro Rail Limited Corridor 4, and intends to apply part of the proceeds toward payments under the contract for Construction of Elevated Metro Stations at Power House, Vadapalani, Saligramam, Avichi School, Alwartiru Nagar, Valasaravakkam, Karambakkam, Alapakkam Junction, Porur Junction & Associated Viaduct from Chainage 10027.102 to Chainage 17982.240 and all associated works (herein after called as “Package C4-ECV-01”) 2. Chennai Metro Rail Limited (CMRL) an implementing agency, now invites online tenders from eligible Tenderers for Package C4-ECV 01 fulfilling the qualification criteria as mentioned in the tender document under single stage two envelop (Technical & Financial) system as detailed in the Table below. The duration of the contract (completion period of work) is 36 months. Tenderers are advised to note the clauses on eligibility (Section 1 Clause 4), minimum qualification criteria (Section 3 – Evaluation and Qualification Criteria), to qualify for the award of the contract. In addition, please refer to paragraphs 4.4.1 and 4.4.2 of the “INTERIM OPERATIONAL DIRECTIVES on Procurement Instructions for Recipient” setting forth the AIIB’s policy on conflict of interest. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2011 [Price: Rs. 25.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 23] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, 2011 Aani 7, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Change of Names .. 1245-1308 1119 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES My son, H. Dhamodaran, son of Thiru S.B. Harikrishnarajh, My son, Mohammed Azeez, born on 4th February 2007 born on 24th January 1996 (native district: Tiruvallur), residing (native district: Vellore), residing at No. 73, 3rd Street, at No. 31/2, Balasubramaniam Street, VOC Block, Gaffarbad, Vaniyambadi, Vellore-635 751, shall henceforth Jafferkanpet, Chennai-600 083, shall henceforth be known be known as I MD SHUBAZ. as S.H. VIJAYDAMODAR. M. ILIYAS AHMED. H. GOMATHI. Vaniyambadi, 13th June 2011. (Father.) Chennai, 13th June 2011. (Mother.) I, L. Violet, wife of Thiru M.M. Luke, born on My daughter, C. Muthumeena, born on 3rd August 1993 3rd August 1960 (native district: Salem), residing at (native district: Chennai), residing at Old No. 1/98A, New No. 618, Perfume Paradise, Lady Seat Road, Yercaud, No. 3/241, Neelankarai, Sengeni Amman Koil Street, Salem-636 601, shall henceforth be known Tambaram, Chennai-600 041, shall henceforth be known as as L NAVIS VIOLET. -

District Statistical Hand Book Chennai District 2016-2017

Government of Tamil Nadu Department of Economics and Statistics DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK CHENNAI DISTRICT 2016-2017 Chennai Airport Chennai Ennoor Horbour INDEX PAGE NO “A VIEW ON ORGIN OF CHENNAI DISTRICT 1 - 31 STATISTICAL HANDBOOK IN TABULAR FORM 32- 114 STATISTICAL TABLES CONTENTS 1. AREA AND POPULATION 1.1 Area, Population, Literate, SCs and STs- Sex wise by Blocks and Municipalities 32 1.2 Population by Broad Industrial categories of Workers. 33 1.3 Population by Religion 34 1.4 Population by Age Groups 34 1.5 Population of the District-Decennial Growth 35 1.6 Salient features of 1991 Census – Block and Municipality wise. 35 2. CLIMATE AND RAINFALL 2.1 Monthly Rainfall Data . 36 2.2 Seasonwise Rainfall 37 2.3 Time Series Date of Rainfall by seasons 38 2.4 Monthly Rainfall from April 2015 to March 2016 39 3. AGRICULTURE - Not Applicable for Chennai District 3.1 Soil Classification (with illustration by map) 3.2 Land Utilisation 3.3 Area and Production of Crops 3.4 Agricultural Machinery and Implements 3.5 Number and Area of Operational Holdings 3.6 Consumption of Chemical Fertilisers and Pesticides 3.7 Regulated Markets 3.8 Crop Insurance Scheme 3.9 Sericulture i 4. IRRIGATION - Not Applicable for Chennai District 4.1 Sources of Water Supply with Command Area – Blockwise. 4.2 Actual Area Irrigated (Net and Gross) by sources. 4.3 Area Irrigated by Crops. 4.4 Details of Dams, Tanks, Wells and Borewells. 5. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 5.1 Livestock Population 40 5.2 Veterinary Institutions and Animals treated – Blockwise.