Chronicles and the Reception of Lamentations As Two Modes of Interacting with the Jeremianic Tradition?1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structure and Meaning in Lamentations Homer Heater Liberty University, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School 1992 Structure and Meaning in Lamentations Homer Heater Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Heater, Homer, "Structure and Meaning in Lamentations" (1992). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 283. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Structure and Meaning in Lamentations Homer Heater, Jr. Professor of Bible Exposition Dallas Theological Seminary, Dallas, Texas Lamentations is perhaps the best example in the Bible of a com bination of divine inspiration and human artistic ability. The depth of pathos as the writer probed the suffering of Zion and his own suf fering is unprecedented. Each chapter is an entity in itself, a com plete poem.1 The most obvious literary device utilized by the poet is the acrostic; that is, poems are built around the letters of the alpha bet. -

The Prophet Jeremiah As Theological Symbol in the Book of Jeremiahâ•Š

Scholars Crossing LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations 11-2010 The Prophet Jeremiah as Theological Symbol in the Book of Jeremiah” Gary E. Yates Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Yates, Gary E., "The Prophet Jeremiah as Theological Symbol in the Book of Jeremiah”" (2010). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 372. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/372 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETS, Atlanta 2010 “The Prophet Jeremiah as Theological Symbol in the Book of Jeremiah” Gary E. Yates, Ph.D. Introduction Timothy Polk has noted, “Nothing distinguishes the book of Jeremiah from earlier works of prophecy quite so much as the attention it devotes to the person of the prophet and the prominence it accords the prophetic ‘I’, and few things receive more scholarly comment.”1 More than simply providing a biographical or psychological portrait of the prophet, the book presents Jeremiah as a theological symbol who embodies in his person the word of Yahweh and the office of prophet. 2 In fact, the figure of Jeremiah is so central that a theology of the book of Jeremiah “cannot be formulated without taking into account the person of the prophet, as the book presents him.”3 The purpose of this study is to explore how Jeremiah the person functions as a theological symbol and what these motifs contribute to the overall theology of the book of Jeremiah. -

It Is Difficult to Speak About Jeremiah Without Comparing Him to Isaiah. It

751 It is diffi cult to speak about Jeremiah without comparing him to Isaiah. It might be wrong to center everything on the differences between their reactions to God’s call, namely, Isaiah’s enthusiasm (Is 6:8) as opposed to Jeremiah’s fear (Jer 1:6). It might have been only a question of their different temperaments. Their respec- tive vocation and mission should be complementary, both in terms of what refers to their lives and writings and to the infl uence that both of them were going to exercise among believers. Isaiah is the prophecy while Jeremiah is the prophet. The two faces of prophet- ism complement each other and they are both equally necessary to reorient history. Isaiah represents the message to which people will always need to refer in order to reaffi rm their faith. Jeremiah is the ever present example of the suffering of human beings when God bursts into their lives. There is no room, therefore, for a sentimental view of a young, peaceful and defenseless Jeremiah who suffered in silence from the wickedness of his persecu- tors. There were hints of violence in the prophet (11:20-23). In spite of the fact that he passed into history because of his own sufferings, Jeremiah was not always the victim of the calamities that he had announced. In his fi rst announcement, Jeremiah said that God had given him authority to uproot and to destroy, to build and to plant, specifying that the mission that had been entrusted to him encompassed not only his small country but “the nations.” The magnitude to such a task assigned to a man without credentials might surprise us; yet it is where the fi nger of God does appear. -

The Suffering of the Prophet Jeremiah

MINISTRY The Suffering of the Prophet Jeremiah Drs. H. Lalleman-de Winkel graduated from Utrecht State University, taking Old Testament as her main subject. She wrote a thesis on Medical Metaphors in the Book of Jeremiah, and ·continues research on that book. We live in a remarkable time. In our western world with its Biographical Sections. material prosperity we can get almost everything we want. Even In those parts of the book which tell of Jeremiah' s life, what we if not all are rich, generally speaking we have more than we really read in the story of his call is developed: his message ofjudgment need. Yet even in our modern world money cannot buy freedom is not accepted with enthusiasm; indeed the story has been called from sorrow and suffering. So many books are written on this a 'passion narrative'. Let us consider some of these reports which theme nowadays, (for instance the book by Harold S. Kushner relate to Jeremiah's suffering. When bad things happen to good people•), along with books about: how to be healthy, successful in business, etc. Suffering Jeremiah 20: 1-2 describes how Jeremiah is captured by the chief does not agree with our success, and so it hardly figures in our officer in the temple, Pashhur; he is considered a disturber of the thinking. The book of Jeremiah offers one model of suffering. peace (cf. 29:26, apparently this happened more often). People Even if the suffering of Jeremiah has certain specific meanings take offence at his message of judgment, he is beaten and put in which do not apply to suffering in general, some analogies with a kind of straitjacket. -

The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context

The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context kevin l. tolley Kevin L. Tolley ([email protected]) is the coordinator of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion in Fullerton, California. he book of Jeremiah describes the turbulent times in Jerusalem prior to Tthe Babylonian conquest of the city. Warring political factions bickered within the city while a looming enemy rapidly approached. Amid this com- . (wikicommons). plex political arena, Jeremiah arose as a divine spokesman. His preaching became extremely polarizing. These political factions could be categorized along a spectrum of support and hatred toward the prophet. Jeremiah’s imprisonment (Jeremiah 38) illustrates some of the various attitudes toward God’s emissary. This scene also demonstrates the political climate and spiritual atmosphere of Jerusalem at the verge of its collapse into the Babylonian exile and also gives insights into the beginning narrative of the Book of Mormon. Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem Jeremiah Setting the Stage: Political Background for Jeremiah’s Imprisonment In the decades before the Babylonian exile in 587/586 BC, Jerusalem was the center of political and spiritual turmoil. True freedom and independence had Rembrandt Harmensz, Rembrandt not been enjoyed there for centuries.1 Subtle political factions maneuvered The narrative of the imprisonment of Jeremiah gives us helpful insights within the capital city and manipulated the king. Because these political into the world of the Book of Mormon and the world of Lehi and his sons. RE · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 · 97–11397 98 Religious Educator ·VOL.20NO.3·2019 The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context 99 groups had a dramatic influence on the throne, they were instrumental in and closed all local shrines, centralizing the worship of Jehovah to the temple setting the political and spiritual stage of Jerusalem. -

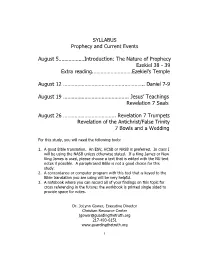

Prophecy and Current Events

SYLLABUS Prophecy and Current Events August 5………………Introduction: The Nature of Prophecy Ezekiel 38 - 39 Extra reading.………………………Ezekiel’s Temple August 12 …………………………………….………….. Daniel 7-9 August 19 ………………………………………. Jesus’ Teachings Revelation 7 Seals August 26 ………………………………. Revelation 7 Trumpets Revelation of the Antichrist/False Trinity 7 Bowls and a Wedding For this study, you will need the following tools: 1. A good Bible translation. An ESV, HCSB or NASB is preferred. In class I will be using the NASB unless otherwise stated. If a King James or New King James is used, please choose a text that is edited with the NU text notes if possible. A paraphrased Bible is not a good choice for this study. 2. A concordance or computer program with this tool that is keyed to the Bible translation you are using will be very helpful. 3. A notebook where you can record all of your findings on this topic for cross referencing in the future; the workbook is printed single sided to provide space for notes. Dr. JoLynn Gower, Executive Director Christian Resource Center [email protected] 217-493-6151 www.guardingthetruth.org 1 INTRODUCTION The Day of the Lord Prophecy is sometimes very difficult to study. Because it is hard, or we don’t even know how to begin, we frequently just don’t begin! However, God has given His Word to us for a reason. We would be wise to heed it. As we look at prophecy, it is helpful to have some insight into its nature. Prophets see events; they do not necessarily see the time between the events. -

2. Ezra 1-6.Indd

EZRA 1-6 THE EXILES RETURN 21 Cyrus’s edict 1In the first year of King Cyrus of Persia, in Cyrus became king of Anshan in order that the word of YHWH by the mouth 559. After defeating Astyarges of Jeremiah might be accomplished, YHWH of Media and capturing Sardis in stirred up the spirit of King Cyrus of Per- Asia Minor, he entered Babylon sia so that he sent a herald throughout all in triumph in 539. his kingdom, and also in a written edict 2 The author sees the working of declared: “Thus says King Cyrus of Persia: YHWH in the rebuilding of the YHWH, the God of heaven, has given me temple, which was destroyed in all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has 586 and re-consecrated in 516. He charged me to build him a house at Jerusa- 3 links this with the seventy years lem in Judah. Any of those among you who prophesied by Jeremiah (verse are of his people – may their God be with 1; see Jeremiah 29:10). He por- them! – are now permitted to go up to Je- trays Cyrus as being directed by rusalem in Judah, and rebuild the house of YHWH. We are reminded of the YHWH, the God of Israel. He is the God who 4 authors of the Isaiah scroll who is in Jerusalem. Let all survivors, in whatev- saw Cyrus as YHWH’s messiah er place they reside, be assisted by the peo- (see Isaiah 45:1, 13). ple of their place with silver and gold, with goods and with animals, besides freewill of- The Chronicler chose to conclude ferings for the house of God in Jerusalem.” his re-writing of the story of the 5 kings of Judah by quoting from The heads of the families of Judah and Ezra 1:1-3 (see 2Chronicles Benjamin, and the priests and the Levites 36:22-23). -

Narrative Parallelism and the "Jehoiakim Frame": a Reading Strategy for Jeremiah 26-45

Scholars Crossing LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations 6-2005 Narrative Parallelism and the "Jehoiakim Frame": a Reading Strategy for Jeremiah 26-45 Gary E. Yates Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Yates, Gary E., "Narrative Parallelism and the "Jehoiakim Frame": a Reading Strategy for Jeremiah 26-45" (2005). LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations. 5. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in LBTS Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JETS 48/2 (June 2005) 263-81 NARRATIVE PARALLELISM AND THE "JEHOIAKIM FRAME": A READING STRATEGY FOR JEREMIAH 26-45 GARY E. YATES* I. INTRODUCTION Many attempting to make sense of prophetic literature in the Hebrew Bible would echo Carroll's assessment that "[t]o the modern reader the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel are virtually incomprehensible as books."1 For Carroll, the problem with reading these books as "books" is that there is a confusing mixture of prose and poetry, a lack of coherent order and arrange ment, and a shortage of necessary contextual information needed for accu rate interpretation.2 Despite the difficult compositional and historical issues associated with the book of Jeremiah, there is a growing consensus that -

1 Context Overview 2 Outline of Ezekiel 26

Author: Ron Graham EEzzeekkiieell CChhaapptteerrss 2266,, 2277 aanndd 2288 —Outline and Notes 1 Context Overview Jerusalem has been under siege by Nebudchadnezzar king of Babylon, and finally the city has been ransacked and brought to ruin. Many Israelites were killed, many taken captive to Babylon, and some escaped. So Israel now consisted of the slaughtered in Jerusalem, the exiles in Babylon, and the fugitives among other nations. Ezekiel was among the exiles in Babylon who had been taken captive years earlier. He was appointed by God to watch over the Israelite captives and teach them by sharing his visions, preaching oracles from God, and performing symbolic acts. Not many paid heed to Ezekiel. King Nebuchadnezzar was attacking other nations besides Judah, and other cities besides Jerusalem. Prominent among these was the kingdom and city of Tyre. God promised that Tyre, because it had become corrupt, would be attacked by the Babylonians and by "many nations" and eventually be destroyed like Jerusalem. Ezekiel delivers God’s counsel to Tyre in a series of prophecies, laments, and oracles. 2 Outline of Ezekiel 26 11th YEAR (Ezekiel 26:1). Prophecy Against Tyre Jerusalem is in ruins and Judah is desolate. The coastal kingdom of Tyre thinks that opens the gate for Tyre to expand and profit. (Ezekiel 26:1-2). But God is against Tyre, and the kingdom will eventually suffer the same ruin as Jerusalem. This will result from "many nations" making wave after wave of assault (Ezekiel 26:3-6). Nebuchadnezzar will Attack Tyre Babylon will be the first of the nations to attack Tyre. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

Ezra & Nehemiah- Week of August 27 Day 1- Ezra 5-6 Pray That God

Ezra & Nehemiah- Week of August 27 Day 1- Ezra 5-6 Pray that God would open your mind and heart to understand and be transformed by His Word. Read Ezra 5:1-6:12 two times. As you read, circle God’s name. Remember at the end of Ezra 4, because of the opposition the people were facing, the work on the house of the Lord stopped. Ezra 4 ends in despair and defeat—it seems that God and His people have lost. In Ezra 5, what do Zerubbabel and Jeshua do? Verse 1 makes a connection to 2 prophets of that time. What did Haggai and Zechariah prophesy? See Haggai 1:1,7-8 and Zechariah 1:1-3. The people of God meet some opposition again from Tattenai and Shethar-bozenai, two local leaders. This opposition does not seem to be as harsh, but they are questioned about what they are doing in Jerusalem in Ezra 5:3-4. This time the work on the temple does not stop. According to the passage, why does the work continue? (vs. 5) The questioners, Tattenai and Shethar-bozenai write a letter to King Daruis to inform him of what is going on. They tell him that they have questioned the people, and they tell him the people’s response. What was the people’s response to their questioning (Ezra 5:11-17)? King Darius receives this letter and launches an investigation of his own. What is his response (Ezra 6:6-12)? What significance in there in King Darius’s words, especially in Ezra 6:12? Why would Darius, a king who probably did not know God, respond this way (think back to King Cyrus in Chapter 1)? We noticed in Ezra 1 (and in Exodus 12:31) that God freed His people for a specific purpose. -

![The Book of Lamentations, an Introductory Study [Texas Pastoral Study Conference, April 28, 1981] By: Pastor Thomas Valleskey](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4364/the-book-of-lamentations-an-introductory-study-texas-pastoral-study-conference-april-28-1981-by-pastor-thomas-valleskey-734364.webp)

The Book of Lamentations, an Introductory Study [Texas Pastoral Study Conference, April 28, 1981] By: Pastor Thomas Valleskey

The Book of Lamentations, an Introductory Study [Texas Pastoral Study Conference, April 28, 1981] by: Pastor Thomas Valleskey The Name of the Book and its Place in the Canon meaning, “Ah, how!” In ,אביה ,In the Hebrew text the Book is named after its first word the Septuagint, however, the book receives its name from the contents of the book. The Septuagint title simply reads qrenoi (tears) and adds a subscript ‘of Jeremiah.’ The Latin Vulgate retains the title ‘tears’ (threni) and adds the interpretation, ‘id est lamentationes Jeremiae prophetae’. It is from the Vulgate that the English translations take their title for this book, The Lamentations of Jeremiah. In the Hebrew canon Lamentations was placed just after Ruth in the Megilloth (rolls)of the Kethubhim (writings) or Hagiographa (sacred writings), the Hebrew canon being divided into the torah (the writings of Moses), the nebhim (the writings of the called prophets) and the ketubhim (the writings of other holy men of God). The Septuagint places Lamentations after the prophecy of Jeremiah and the apocryphal book of Baruch, and this position was later adopted by the other versions, including the Vulgate. The English versions (and Luther) adopt the Septuagint placement of the book. The authenticity of its place in the Old Testament canon has never been questioned. The Authorship of Lamentations According to both Jewish and Christian tradition the author of Lamentations was the Prophet Jeremiah. This tradition already appears in the Septuagint, “And it came to pass after Israel had been taken away into captivity and Jerusalem had been laid waste that Jeremiah sat weeping and lamented this lamentation over Jerusalem and said.” The Vulgate repeats these words and adds to them, “with a bitter spirit sighing and wailing.” The early Church Fathers, such as Origen and Jerome, unanimously accepted Jeremiah as the author of this book.