Lynn Swann for Use Anytime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NFL-USO Tour to Take Place in Japan

7/19/18 NFL-USO Tour to Take Place in Japan As Part of NFL’s Salute to Service and USO partnership, Donnie Edwards, Tony Richardson and Amani Toomer to Visit U.S. Service Members and Families DONNIE EDWARDS, TONY RICHARDSON and AMANI TOOMER will embark on the first All- NFL Legends, week-long USO tour throughout Japan to visit U.S. service members and their families at military bases, the NFL announced today. An extension of Salute to Service – the League’s year-round effort to honor, empower and connect service members, veterans and their families through a unifying lens of football and strategic partnerships – this year’s NFL-USO tour will visit service members and families at multiple installations and observe missions ranging from crash and rescue to engineering, as well as visit high school football players. “The NFL remains committed to honoring and giving back to the men and women in uniform who sacrifice so much to protect our country,” said ANNA ISAACSON, NFL Senior Vice President of Social Responsibility. “We are excited to partner with the USO on another goodwill tour and continue strengthening our connections to our nation’s service members.” Throughout the week, the players will spend quality time with Airmen, Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, and their families, meet with installation commanders and participate in unit visits. The NFL Legends will also take part in a military working dog demonstration, visit an air defense artillery unit, and a close-up view of aircraft and the maintainers who keep them in the air. “For more than 50 years, the USO and NFL have partnered to bring a piece of home to service members no matter where they are in the world,” said KRISTINA GRIFFIN, USO Corporate Alliances Senior Director. -

Sun Devil Legends

SUN DEVIL LEGENDS over North Carolina. Local sports historians point to that game as the introduction of Arizona State Frank Kush football to the national scene. Five years later, the Sun Devils again capped an undefeated season by ASU Coach, 1958-1979 downing Nebraska, 17-14. The win gave ASU a No. In 1955, Hall of Fame coach Dan Devine hired 2 national ranking for the year, and ushered ASU Frank Kush as one of his assistants at Arizona into the elite of college football programs. State. It was his first coaching job. Just three years • The success of Arizona State University football later, Kush succeeded Devine as head coach. On under Frank Kush led to increased exposure for the December 12, 1995 he joined his mentor and friend university through national and regional television in the College Football Hall of Fame. appearances. Evidence of this can be traced to the Before he went on to become a top coach, Frank fact that Arizona State’s enrollment increased from Kush was an outstanding player. He was a guard, 10,000 in 1958 (Kush’s first season) to 37,122 playing both ways for Clarence “Biggie” Munn at in 1979 (Kush’s final season), an increase of over Michigan State. He was small for a guard; 5-9, 175, 300%. but he played big. State went 26-1 during Kush’s Recollections of Frank Kush: • One hundred twenty-eight ASU football student- college days and in 1952 he was named to the “The first three years that I was a head coach, athletes coached by Kush were drafted by teams in Look Magazine All-America team. -

CHUCK NOLL HALL of FAME “GAME for LIFE” AWARD to HONOR YOUTH FOOTBALL PROGRAMS Award Created by Merril Hoge Celebrates Pro Football Hall of Fame Coach Chuck Noll

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 8/2/17 Contact: Pete Fierle, Pro Football Hall of Fame, (330) 588-3622 Melinda Whitemarsh, USA Football, (317) 489-4431 CHUCK NOLL HALL OF FAME “GAME FOR LIFE” AWARD TO HONOR YOUTH FOOTBALL PROGRAMS Award Created by Merril Hoge Celebrates Pro Football Hall of Fame Coach Chuck Noll CANTON, OHIO – The Pro Football Hall of Fame, in partnership with USA Football, is teaming with DICK’S Sporting Goods, Riddell and adidas to introduce the Chuck Noll Hall of Fame “Game for Life” Award. The honor will be presented to youth football programs in every state that exemplify the values of football: commitment, integrity, courage, respect, and excellence. As he taught America’s favorite sport, legendary Hall of Fame coach CHUCK NOLL personified these timeless values, which are foundational to the game and championed by Pro Football Hall of Fame and USA Football. Leagues that earn the Chuck Noll Hall of Fame “Game for Life” Award will be recognized for their commitment to coaching education; best practices in player safety; teaching lessons about how to win rather than emphasizing winning; and nurturing a culture that celebrates preparation, discipline, accountability and respect through the fun and fitness of football and how it applies to success beyond the field. These winning attributes parallel the philosophies for which Coach Noll stood and are supported for the good of young athletes by the Pro Football Hall of Fame, USA Football, DICK’S Sporting Goods and The DICK’S Sporting Goods Foundation’s Sports Matter program, Riddell and adidas. Each of the 50 recognized youth leagues will receive: • $500 equipment grant from Riddell and USA Football; • $500 gift card from DICK’S Sporting Goods • $500 gift card from adidas. -

Chiefs Lose Again KANSAS CTIY (UPI) Ken Stabler, Score

Sports ..w Chiefs lose again KANSAS CTIY (UPI) Ken Stabler, score. opening period. using 42-1- an assortment of receivers and MacArthur Lane boomed his way one Kansas City, a 0 victor over passing at will, threw for three yard into the end zone with 1:45 left in Oakland on national TV a year ago, touchdowns Monday night in guiding the third quarter to cap a 57-ya- rd once again turned the ball over after the Oakland Raiders to a 24-2-1 Chiefs' drive in which running back three plays and Stabler went back to nationally-televise- d win over the Woody Green gained 42 yards. work, masterminding a 72-ya- rd, 12-pl- ay Kansas City Chiefs. The Chiefs struck quickly in the drive which ended when he found Stabler, who left the game with less closing minutes First they put together Branch all alone in the right corner of than 13 minutes to play when his right an 86-ya- rd drive which ended with the end zone. knee was banged up by Chiefs quarterback Mike Livingston running The Chiefs, held to 10 yards rushing in defensive end Wilbur Young, completed one yard for the touchdown with 4:36 to the first half, showed their first signs of 22 of 28 passes with one interception for play. This came just 10 plays after off- offense on the opening possession of the 224 yards 55-ya-rd back-to-ba- and threw to seven different setting penalties had nullified a third quarter as Livingston hit ck receivers, including Fred Biletnikoff touchdown pass from the former SMU passes of 25 and 24 yards to White who caught four passes to raise his star to tight end Walter White. -

Franco Harris President, Super Bakery Former Steeler & Pro Football Hall

Franco Harris President, Super Bakery Former Steeler & Pro Football Hall of Famer Franco Harris is well known for his outstanding career in the National Football League, one so productive that it earned him a 1990 induction into The Pro Football Hall of Fame. He also was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2011. During his years with the Pittsburgh Steelers, Harris set the standard for NFL running backs - big, fast and agile with explosive cutback ability. He established many team and league records, played in nine Pro Bowls, and led the Steelers’ charge to four Super Bowl victories. Franco was named MVP of Super Bowl IX. His “Immaculate Reception” in the final seconds of the 1972 AFC playoff game against the Oakland Raiders is considered to be the greatest individual play in NFL history. After football, Harris applied himself to his college degree in Food Service and Administration. He started out in the early 1980’s with a small distribution company called Franco’s All Naturèl, focusing on high quality, natural products. This is where and how Harris learned the business, driving thousands of miles, meeting with potential customers, c-store chains and distributors. He warehoused, sold, promoted and sometimes even delivered Franco’s FROZEFRUIT and his other all-natural products. In 1990 Harris established Super Bakery with the goal of making it The Leader in Bakery Nutrition. Super Donuts and Super Buns are made with no artificial flavors, colors, or preservatives and are fortified with NutriDough, a special dough of Minerals, Vitamins and Protein. Super Donuts and Super Buns are sold to school systems across America, providing MVP Nutrition! to millions of students each year. -

North America's Charity Fundraising

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: California Autographed Sports Memorabilia Inventory Updated 10/04/2013 California Angels 1. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $380.00 2. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001-02) $175.00 3. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001-02) $201.00 4. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $305.00 5. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001- 02) $150.00 6. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001-02) $175.00 LA Dodgers 1. Dusty Baker Los Angeles Dodgers Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $285.00 2. Autographed Pedro Guerrero Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $265.00 3. Autographed Pedro Guerrero MLB Baseball (BWU001-02) $150.00 4. Autographed Orel Hershiser Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001-02) $325.00 5. Autographed Orel Hershiser Baseball Inscribed 88 WS MVP and 88 WS Cy Young (BWU001-02) $190.00 6. -

The Magnificent Seven

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 26, No. 4 (2004) THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN by Coach TJ Troup The day after Christmas in 1954 the Cleveland Browns hosted the Detroit Lions for the NFL title. It was the third consecutive year these two teams would decide the championship. The Browns had lost three consecutive championship games, including the last two to the Lions. Browns QB Otto Graham had not played particulary well in those three losses, and since he was the “trigger” man in the Cleveland offense, and a man of intense pride, this was the “crossroads” game of his career. Graham responded to the challenge by contributing five touchdowns in a 56 to 10 victory. Otto completed 9 of 12 passes for 163 yards and 2 touchdowns, and scored 3 himself on short runs from scrimmage. Though he announced his retirement, Otto eventually returned for one final season in 1955. Graham again led the Browns to the title, this time defeating the Rams in the Los Angeles Coliseum 38 to 14. When assessing a quarterback’s career how much emphasis should be placed on his passing statistics? Long after Otto Graham retired, the NFL began to use the passer rating system to evaluate the passing efficiency of each individual quarterback. Using that system how efficient was Graham, and where does he rank in comparison with other champion quarterbacks? The passer rating system is divided into four equal categories; completion percentage per pass attempt, yards gained per pass attempt, touchdown percentage per pass attempt, and interception percentage per pass attempt. Is there a simpler way of stating this? We want our team to complete as many long passes for as many touchdowns as possible in as few attempts as possible, without throwing an interception. -

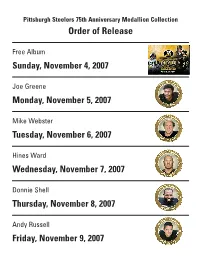

PSL Medallion Release Order.V1

Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Free Album Sunday, November 4, 2007 Joe Greene Monday, November 5, 2007 Mike Webster Tuesday, November 6, 2007 Hines Ward Wednesday, November 7, 2007 Donnie Shell Thursday, November 8, 2007 Andy Russell Friday, November 9, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Carnell Lake Saturday, November 10, 2007 Terry Bradshaw Sunday, November 11, 2007 Casey Hampton Monday, November 12, 2007 Rocky Bleier Tuesday, November 13, 2007 Greg Lloyd Wednesday, November 14, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Elbie Nickel Thursday, November 15, 2007 Rod Woodson Friday, November 16, 2007 Larry Brown Saturday, November 17, 2007 Lynn Swann Sunday, November 18, 2007 Dermontti Dawson Monday, November 19, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Bobby Walden Tuesday, November 20, 2007 Joey Porter Wednesday, November 21, 2007 Jack Ham Thursday, November 22, 2007 Tunch Ilkin Friday, November 23, 2007 Gary Anderson Saturday, November 24, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Franco Harris Sunday, November 25, 2007 Commemorative Medallion Monday, November 26, 2007 L.C. Greenwood Tuesday, November 27, 2007 Jack Butler Wednesday, November 28, 2007 Jon Kolb Thursday, November 29, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Dwight White Friday, November 30, 2007 Ernie Stautner Saturday, December 1, 2007 Jerome Bettis Sunday, December 2, 2007 Alan Faneca Monday, December 3, 2007 Bennie Cunningham Tuesday, December 4, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Troy Polamalu Wednesday, December 5, 2007 Mel Blount Thursday, December 6, 2007 John Stallworth Friday, December 7, 2007 Bonus Coupon Saturday, December 8, 2007 BONUS COUPON for any previously released medallion Here is a chance to collect any medallion you may have missed so far. -

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER the Following Players Comprise the 1967 Season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1967 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA ATLANTA BALTIMORE BALTIMORE OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Tommy McDonald End: Sam Williams EB: Willie Richardson End: Ordell Braase Jerry Simmons TC OC Jim Norton Raymond Berry Roy Hilton Gary Barnes Bo Wood OC Ray Perkins Lou Michaels KA KOA PB Ron Smith TA TB OA Bobby Richards Jimmy Orr Bubba Smith Tackle: Errol Linden OC Bob Hughes Alex Hawkins Andy Stynchula Don Talbert OC Tackle: Karl Rubke Don Alley Tackle: Fred Miller Guard: Jim Simon Chuck Sieminski Tackle: Sam Ball Billy Ray Smith Lou Kirouac -

Hall of Fame Admission Promotion Offered to Steelers and Browns Fans

Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE @ProFootballHOF 11/17/2016 Contact: Pete Fierle, Chief of Staff & Vice President of Communications [email protected]; 330-588-3622 HALL OF FAME ADMISSION PROMOTION OFFERED TO STEELERS AND BROWNS FANS FANS VISITING REGION FOR THE WEEK 11 MATCH-UP TO RECEIVE SPECIAL ADMISSION DISCOUNT FOR WEARING TEAM GEAR CANTON, OHIO – The Pro Football Hall of Fame is inviting Pittsburgh Steelers and Cleveland Browns fans in northeast Ohio this weekend to experience “The Most Inspiring Place on Earth!” The Steelers take on the Browns this Sunday (Nov. 20) at 1:00 p.m. at FirstEnergy Stadium. The Pro Football Hall of Fame is just under an hour’s drive south of Cleveland. Any Steelers or Browns fan dressed in their team’s gear who mentions the promotion at the Hall’s box office will receive a $5 discount on any regular price museum admission. The promotion runs from Friday, Nov. 18 through Monday, Nov. 21. The Hall of Fame is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Information about planning a visit to the Hall of Fame can be found at: www.ProFootballHOF.com/visit/. STEELERS IN CANTON The Steelers have 21 longtime members enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame – the third most by any current NFL franchise after the Chicago Bears (27) and the Green Bay Packers (24). Longtime Pittsburgh players include: JEROME BETTIS (Running Back, 1996-2005, Class of 2015), MEL BLOUNT (Cornerback, 1970-1983, Class of 1989), TERRY BRADSHAW -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games. -

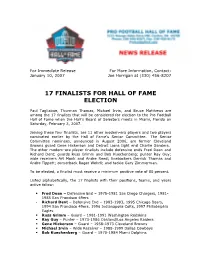

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999