La Sonnambula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Singing Telegram

THE SINGING TELEGRAM Happy almost New Year! Well, New Year from the perspective of LOON’s season, at any rate! As we close out this season with the fun and shimmer of our Summer Sparkler, we reflect back on the year while we also look forward to the season to come. Thanks to all who made Don Giovanni such a success! Host families, yard sign posters, volunteer painters, stitchers, poster-hangers, ushers, and donors are a part of the success of any production, right along with the singers, designers, orchestra, and tech crew. Thanks to ALL for bringing this imaginative and engaging produc- tion to the stage! photos by: Michelle Sangster IT’S THE ROOKIE HUDDLE! offered to a singer who can’t/shouldn’t sing a certain role. What The Fach?! Let’s break that down a little more! Character What if we told you that SOPRANO, ALTO, TENOR, BASS Opera is all about telling stories. Sets, costumes, and lights is just the beginning of the types of voices wandering this give us information about time and place. The narrative planet. There are SO MANY VOICES! In this installation of and emotional details of the story are found in the music the Rookie Huddle we’ll talk about how opera singers – and as interpreted by the orchestra and singers. The singers are the people who hire them – rely on a system of transformed with wigs, makeup, and costumes, but their classification called Fach, which breaks those categories into characters are really found in the voice. many more specific parts. -

Voix Nouvelles, Concert Des Lauréats

Concert Voix Nouvelles du mercredi Concert des lauréats du Concours Voix Nouvelles 2018 me 12 décembre 18h PROG_VOIX NOUVELLES_140190.indd 1 04/12/2018 16:22 Hélène Carpentier ©Harcourt Caroline Jestaedt ©DR Eva ZAÏCIK ©Philippe Biancotto Gilen Goicoechea ©DR Concert des lauréats du Concours Voix Nouvelles 2018 PROG_VOIX NOUVELLES_140190.indd 2 04/12/2018 16:22 Concert du Mercredi en Grande Salle Surtitré en français +/- 1h10 sans entracte Caroline Jestaedt ©DR Concert des lauréats du Concours Voix Nouvelles 2018 Voix Nouvelles Avec Hélène Carpentier soprano Caroline Jestaedt soprano Eva Zaïcik mezzo-soprano Gilen Goicoechea baryton Gilen Goicoechea ©DR Direction musicale Cyril Diederich Orchestre de Picardie Concert des lauréats du Concours Voix Nouvelles 2018 Le Concours Voix Nouvelles est co-organisé par le Centre Français de Promotion Lyrique, la Fondation Orange et la Caisse des Dépôts, avec le soutien du Ministère de la Culture, du Ministère des Outre-Mer et de l’Adami, en partenariat avec France 3, France Musique et TV5 Monde PROG_VOIX NOUVELLES_140190.indd 3 04/12/2018 16:22 ••• Programme Airs d’opéras de Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) 1. Ouverture des Noces de Figaro 2. Air de Chérubin : « Voi che sapete » (Les Noces de Figaro) 3. Air du Comte : « Hai già vinta la causa » (Les Noces de Figaro) 4. Duo Comtesse et Susanne « Canzonetta sull’aria » (Les Noces de Figaro) 5. Air de Guglielmo : « Donne mie, la fate a tanti » (Così fan tutte) 6. Trio Fiordiligi, Dorabella, Alfonso : « Soave Sia il vento » (Così fan tutte) 7. Ouverture de Don Giovanni 8. Air de Zerline : « Vedrai carino, se sei buonino » (Don Giovanni) 9. -

Biographies (396.2

ANTONELLO MANACORDA conducteur italien • Formation o études de violon entres autres avec Herman Krebbers à Amsterdam o puis, à partir de 2002, deux ans de direction d’orchestre chez Jorma Panula. • Orchestres o 1997 : il crée, avec Claudio Abbado, le Mahler Chamber Orchestra o 2006 : nommé chef permanent de l’ensemble I Pomeriggi Musicali à Milaan o 2010 : nommé chef permanent du Kammerakademie Potsdam o 2011 : chef permanent du Gelders Orkest o Frankfurt Radio Symphony, BBC Philharmonic, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg, Sydney Symphony, Orchestra della Svizzera Italia, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Stavanger Symphony, Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Hamburger Symphoniker, Staatskapelle Weimar, Helsinki Philharmonic, Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse & Gothenburg Symphony • Fil rouge de sa carrière o collaboration artistique de longue durée avec La Fenice à Venise • Pour la Monnaie o dirigeerde in april 2016 het Symfonieorkest van de Munt in werk van Mozart en Schubert • Projets récents et futurs o Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Don Giovanni & L’Africaine à Frankfort, Lucio Silla & Foxie! La Petite Renarde rusée à la Monnaie, Le Nozze di Figaro à Munich, Midsummer Night’s Dream à Vienne et Die Zauberflöte à Amsterdam • Discographie sélective o symphonies de Schubert avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical - courroné par Die Welt) o symphonies de Mendelssohn également avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical) • Pour en savoir plus o http://www.inartmanagement.com o http://www.antonello-manacorda.com CHRISTOPHE COPPENS Artiste et metteur -

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

La Sonnambula 3 Content

Florida Grand Opera gratefully recognizes the following donors who have provided support of its education programs. Study Guide 2012 / 2013 Batchelor MIAMI BEACH Foundation Inc. Dear Friends, Welcome to our exciting 2012-2013 season! Florida Grand Opera is pleased to present the magical world of opera to the diverse audience of © FLORIDA GRAND OPERA © FLORIDA South Florida. We begin our season with a classic Italian production of Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème. We continue with a supernatural singspiel, Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Vincenzo Bellini’s famous opera La sonnam- bula, with music from the bel canto tradition. The main stage season is completed with a timeless opera with Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata. As our RHWIEWSRÁREPI[ILEZIEHHIHERI\XVESTIVEXSSYVWGLIHYPIMRSYV continuing efforts to be able to reach out to a newer and broader range of people in the community; a tango opera María de Buenoa Aires by Ástor Piazzolla. As a part of Florida Grand Opera’s Education Program and Stu- dent Dress Rehearsals, these informative and comprehensive study guides can help students better understand the opera through context and plot. )EGLSJXLIWIWXYH]KYMHIWEVIÁPPIH[MXLLMWXSVMGEPFEGOKVSYRHWWXSV]PMRI structures, a synopsis of the opera as well as a general history of Florida Grand Opera. Through this information, students can assess the plotline of each opera as well as gain an understanding of the why the librettos were written in their fashion. Florida Grand Opera believes that education for the arts is a vital enrich- QIRXXLEXQEOIWWXYHIRXW[IPPVSYRHIHERHLIPTWQEOIXLIMVPMZIWQSVI GYPXYVEPP]JYPÁPPMRK3RFILEPJSJXLI*PSVMHE+VERH3TIVE[ILSTIXLEX A message from these study guides will help students delve further into the opera. -

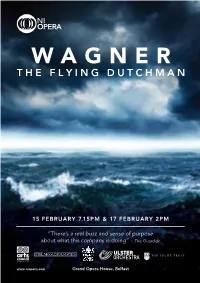

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

La Letteratura Degli Italiani Rotte Confini Passaggi

Associazione degli Italianisti XIV CONGRESSO NAZIONALE Genova, 15-18 settembre 2010 LA LETTERATURA DEGLI ITALIANI ROTTE CONFINI PASSAGGI A cura di ALBERTO BENISCELLI, QUINTO MARINI, LUIGI SURDICH Comitato promotore ALBERTO BENISCELLI, GIORGIO BERTONE, QUINTO MARINI SIMONA MORANDO, LUIGI SURDICH, FRANCO VAZZOLER, STEFANO VERDINO SESSIONI PARALLELE Redazione elettronica e raccolta Atti Luca Beltrami, Myriam Chiarla, Emanuela Chichiriccò, Cinzia Guglielmucci, Andrea Lanzola, Simona Morando, Matteo Navone, Veronica Pesce, Giordano Rodda DIRAS (DIRAAS), Università ISBN 978-88-906601-1-5 degli Studi di Genova, 2012 Dalla Francia all’Italia e ritorno. Percorsi di un libretto d’opera Rita Verdirame «Il tragitto da Milano a Parigi de L’elisir d’amore può anche essere riletto [...] come l’intrecciarsi di due tradizioni, quella dell’opera italiana e quella dell’opera francese, esteticamente distinte, eppure inevitabilmente dialettiche».1 Questa osservazione ci introduce nelle vicende compositive, nei travasi intertestuali e nella mappa degli allestimenti, tra la penisola e oltralpe, di una delle opere più celebri e popolari nel catalogo del melodramma italiano. Era il 12 maggio 1832. Al Teatro della Cannobbiana di Milano l’impresario Alessandro Lanari assisteva al trionfo dell’Elisir d’amore, da lui commissionato a un Donizetti già applauditissimo al Carcano per Anna Bolena, spettacolo inaugurale della stagione milanese del carnevale 1830-31, senza che il trionfo trovasse però conferma nella prima scaligera del marzo dell’anno seguente; Ugo conte di Parigi difatti era stato un mezzo insuccesso. Reduce dalla caduta di due mesi innanzi, il compositore ha con l’Elisir la sua rivincita sia Italia sia a Parigi, dove l’opera viene ripresa il 17 gennaio 1739 con l’entusiastico consenso del pubblico del Théâtre Italien. -

New Releases June 2017

NEW RELEASE JUNE 2017 NEW RELEASES JUNE 2017 www.dynamic.it • [email protected] DYNAMIC Srl • www.dynamic.it • [email protected] 1 NEW RELEASE JUNE 2017 DON CARLO GIUSEPPE VERDI First performed in French at the Paris Opera in 1867, Don Carlo is in many ways an amazingly innovative work. The opera seems to underline Verdi’s shift from the Manichean division between good and evil, which had been a clear, structural element of his dramaturgy up to that point in his career. In this opera, Verdi assembles all his mainstay music theatre themes: power, with its honours and burdens; the contrasts of impossible love; the conflict between father and son; and an oppressed people demanding freedom. Verdi radically revised the score in 1883, using an Italian libretto and reducing the opera from five acts to four. The popularity of Don Carlo has grown unremittingly ever since, with today's critics almost unanimously recognising it as one of Verdi’s greatest masterpieces, an opera that continues to reveal new gems. Daniel Oren is fully in control on the podium, ensuring unanimity between orchestra and singers. The Maestro softens the dark DON CARLO tones of the score, which are well reflected in the visuals, choosing Dramma lirico in four Acts instead to emphasise the various changes of mood. Composer KEY FEATURES GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901) Excellent cast for the opening season of Festival Verdi – Teatro Regio di Parma. Libretto by Resounding success, sustained applause, especially for the Joseph Méry e Camille du Locle bass Michele Pertusi as Filippo II. Italian translation by Achille De Lauzières and Angelo Zanardini Available in CD, DVD, Bluray. -

BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions

95674 BAZZINI Complete Opera Transcriptions Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano Antonio Bazzini 1818-1897 CD1 65’09 CD4 61’30 CD5 53’40 Bellini 4. Fantaisie de Concert Mazzucato and Verdi Weber and Pacini Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 (Il pirata) Op.27 15’08 1. Fantaisie sur plusieurs thêmes Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 1. No.1 – Casta Diva (Norma) 7’59 de l’opéra de Mazzucato 1. No.5 – Act 2 Finale of 2. No.6 – Quartet CD3 58’41 (Esmeralda) Op.8 15’01 Oberon by Weber 7’20 from I Puritani 10’23 Donizetti 2. Fantasia (La traviata) Op.50 15’55 1. Fantaisie dramatique sur 3. Souvenir d’Attila 16’15 Tre fantasie sopra motivi della Saffo 3. Adagio, Variazione e Finale l’air final de 4. Fantasia su temi tratti da di Pacini sopra un tema di Bellini Lucia di Lammeroor Op.10 13’46 I Masnadieri 14’16 2. No.1 11’34 (I Capuleti e Montecchi) 16’30 3. No.2 14’59 4. Souvenir de Transcriptions et Paraphrases Op.17 4. No.3 19’43 Beatrice di Tenda Op.11 16’11 2. No.2 – Variations brillantes 5. Fantaisia Op.40 (La straniera) 14’02 sur plusieurs motifs (La figlia del reggimento) 9’44 CD2 65’16 3. No.3 – Scène et romance Bellini (Lucrezia Borgia) 11’05 Anca Vasile Caraman violin · Alessandro Trebeschi piano 1. Variations brillantes et Finale 4. No.4 – Fantaisie sur la romance (La sonnambula) Op.3 15’37 et un choeur (La favorita) 9’02 2. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House,