THE Alaskan Rainforest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story About Understory Why Everyone on Bald Head Island Should Care

Bald Head Association 910-457-4676 • www.BaldHeadAssociation.com 111 Lighthouse Wynd • PO Box 3030, Bald Head Island, NC 28461 The Story About Understory Why Everyone on Bald Head Island Should Care Bald Head Island is truly unique. As a barrier island, it at ground level. Bald Head Island’s latitudinal position is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and Cape Fear River. BHI has supports both northern and southern species of plants.” 14 miles of pristine beaches; 12,400 acres, of which 10,000 acres Important understory plants include vines, small plants and are protected; over 244 species of birds, including the bald eagle; trees, mosses, lichens and even weeds. All are needed to have and the North Carolina Forest Preserve of nearly 200 acres. a healthy forest habitat. Many extreme forces of nature that have helped shape this The BHIC explains, “Vines play an important role. The very special island include hurricane-force winds, salt water and vines and herbaceous plants intertwine, further developing the salt spray, flooding and drought. There is another force of nature structural integrity of the forest and forming pockets of vegetation that impacts BHI — humans — and with us, development. that provide a base for songbirds to build nests. The vines twist The Bald Head Association is mandated by its Covenants to around the canopy and are the secret to wind protection. These help sustain BHI by managing the buildout of homes and by vines actually weave together the canopy so blowing winds don’t managing vegetation trimming/removal, to help protect its penetrate through the top layer and keep homes, plants, and members’ property values. -

Non-Timber Forest Products

Agrodok 39 Non-timber forest products the value of wild plants Tinde van Andel This publication is sponsored by: ICCO, SNV and Tropenbos International © Agromisa Foundation and CTA, Wageningen, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. First edition: 2006 Author: Tinde van Andel Illustrator: Bertha Valois V. Design: Eva Kok Translation: Ninette de Zylva (editing) Printed by: Digigrafi, Wageningen, the Netherlands ISBN Agromisa: 90-8573-027-9 ISBN CTA: 92-9081-327-X Foreword Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are wild plant and animal pro- ducts harvested from forests, such as wild fruits, vegetables, nuts, edi- ble roots, honey, palm leaves, medicinal plants, poisons and bush meat. Millions of people – especially those living in rural areas in de- veloping countries – collect these products daily, and many regard selling them as a means of earning a living. This Agrodok presents an overview of the major commercial wild plant products from Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific. It explains their significance in traditional health care, social and ritual values, and forest conservation. It is designed to serve as a useful source of basic information for local forest dependent communities, especially those who harvest, process and market these products. We also hope that this Agrodok will help arouse the awareness of the potential of NTFPs among development organisations, local NGOs, government officials at local and regional level, and extension workers assisting local communities. Case studies from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Central and South Africa, the Pacific, Colombia and Suriname have been used to help illustrate the various important aspects of commercial NTFP harvesting. -

Old-Growth Forests

Pacific Northwest Research Station NEW FINDINGS ABOUT OLD-GROWTH FORESTS I N S U M M A R Y ot all forests with old trees are scientifically defined for many centuries. Today’s old-growth forests developed as old growth. Among those that are, the variations along multiple pathways with many low-severity and some Nare so striking that multiple definitions of old-growth high-severity disturbances along the way. And, scientists forests are needed, even when the discussion is restricted to are learning, the journey matters—old-growth ecosystems Pacific coast old-growth forests from southwestern Oregon contribute to ecological diversity through every stage of to southwestern British Columbia. forest development. Heterogeneity in the pathways to old- growth forests accounts for many of the differences among Scientists understand the basic structural features of old- old-growth forests. growth forests and have learned much about habitat use of forests by spotted owls and other species. Less known, Complexity does not mean chaos or a lack of pattern. Sci- however, are the character and development of the live and entists from the Pacific Northwest (PNW) Research Station, dead trees and other plants. We are learning much about along with scientists and students from universities, see the structural complexity of these forests and how it leads to some common elements and themes in the many pathways. ecological complexity—which makes possible their famous The new findings suggest we may need to change our strat- biodiversity. For example, we are gaining new insights into egies for conserving and restoring old-growth ecosystems. canopy complexity in old-growth forests. -

Understory Forest Monitoring: a Guide for Small Forest Managers

Understory Forest Monitoring: A Guide for Small Forest Managers With funding provided by BEFORE: A dense monoculture of invasive periwinkle (Vinca species). AFTER: A diverse mix of native vegetation beginning to establish. It will mature into a lush forest Á oor of native wildÁ owers. Managing a healthy forest is not just about having healthy trees. Foresters, scientists, and private woodland owners have an interest in what is growing on the forest Á oor. A healthy understory can offer: • Flowers for native pollinators • Food for wildlife • Resiliency against invasion by forest weeds • Organic material to build healthier soil • Stable soil that doesn’t erode into nearby streams • Beautiful views while recreating in the forest Just like taking inventory of the forest, measuring tree diameters and spacing, it is also important to monitor the changes over time on the forest Á oor. Herbaceous forest plants tend to reach their peak bloom and cover in mid to late spring (mid-May to mid-June in western Oregon). It’s best to monitor forest understory consistently at this time of year. There are dozens of ways to monitor the understory plants in a forest. Two effective methods are described here. Point intercept method This method is performed by laying out a straight line transect in the forest and documenting what is growing on the forest Á oor at one- foot increments along the transect. West Multnomah Soil & Water Conservation District often sets up multiple transects that are 33’ in length giving us 33 data points per transect. The data gathered from the plots can be used to À nd the average cover of different vegetation types in your forest. -

“Catastrophic” Wildfire a New Ecological Paradigm of Forest Health by Chad Hanson, Ph.D

John Muir Project Technical Report 1 • Winter 2010 • www.johnmuirproject.org The Myth of “Catastrophic” Wildfire A New Ecological Paradigm of Forest Health by Chad Hanson, Ph.D. Contents The Myth of “Catastrophic” Wildfire: A New Ecological Paradigm of Forest Health 1 Preface 1 Executive Summary 4 Myths and Facts 6 Myth/Fact 1: Forest fire and home protection 6 Myth/Fact 2: Ecological effects of high-intensity fire 7 Myth/Fact 3: Forest fire intensity 12 Myth/Fact 4: Forest regeneration after high-intensity fire 13 Myth/Fact 5: Forest fire extent 14 Myth/Fact 6: Climate change and fire activity 17 Myth/Fact 7: Dead trees and forest health 19 Myth/Fact 8: Particulate emissions from high-intensity fire 20 Myth/Fact 9: Forest fire and carbon sequestration 20 Myth/Fact 10: “Thinning” and carbon sequestration 22 Myth/Fact 11: Biomass extraction from forests 23 Summary: For Ecologically “Healthy Forests”, We Need More Fire and Dead Trees, Not Less. 24 References 26 Photo Credits 30 Recommended Citation 30 Contact 30 About the Author 30 The Myth of “Catastrophic” Wildfire A New Ecological Paradigm of Forest Health ii The Myth of “Catastrophic” Wildfire: A New Ecological Paradigm of Forest Health By Chad Hanson, Ph.D. Preface In the summer of 2002, I came across two loggers felling fire-killed trees in the Star fire area of the Eldorado National Forest in the Sierra Nevada. They had to briefly pause their activities in order to let my friends and I pass by on the narrow dirt road, and in the interim we began a conversation. -

Accelerating the Development of Old-Growth Characteristics in Second-Growth Northern Hardwoods

United States Department of Agriculture Accelerating the Development of Old-growth Characteristics in Second-growth Northern Hardwoods Karin S. Fassnacht, Dustin R. Bronson, Brian J. Palik, Anthony W. D’Amato, Craig G. Lorimer, Karl J. Martin Forest Northern General Technical Service Research Station Report NRS-144 February 2015 Abstract Active management techniques that emulate natural forest disturbance and stand development processes have the potential to enhance species diversity, structural complexity, and spatial heterogeneity in managed forests, helping to meet goals related to biodiversity, ecosystem health, and forest resilience in the face of uncertain future conditions. There are a number of steps to complete before, during, and after deciding to use active management for this purpose. These steps include specifying objectives and identifying initial targets, recognizing and addressing contemporary stressors that may hinder the ability to meet those objectives and targets, conducting a pretreatment evaluation, developing and implementing treatments, and evaluating treatments for success of implementation and for effectiveness after application. In this report we discuss these steps as they may be applied to second-growth northern hardwood forests in the northern Lake States region, using our experience with the ongoing managed old-growth silvicultural study (MOSS) as an example. We provide additional examples from other applicable studies across the region. Quality Assurance This publication conforms to the Northern Research Station’s Quality Assurance Implementation Plan which requires technical and policy review for all scientific publications produced or funded by the Station. The process included a blind technical review by at least two reviewers, who were selected by the Assistant Director for Research and unknown to the author. -

Forest Ecosystem Services: Cultural Values

Trees At Work: Economic Accounting for Forest Ecosystem Services in the U.S. South 11 Chapter 2 Forest Ecosystem Services: Cultural Values Melissa M. Kreye, Damian C. Adams, Ramesh Ghimire, Wayde Morse, Taylor Stein, J.M. Bowker WHAT ARE CULTURAL SERVICES? associated ecosystem and human components. However, our understanding of the many factors that give rise to cultural ow we define “culture” and societal well-being related ecosystem services is still a matter of ongoing investigation. to culture depends heavily on who is looking at it, but culture can be generally described as “the customs and H There is good reason for investigating the cultural ecosystem beliefs of a particular group of people that are used to express service values associated with forests: they are critical to our their collectively held values” (Soulbury Commission 2012). understanding of the value of forest land and the benefits of In the context of forests, culturally derived norms, beliefs, forest conservation. The U.S. South is expected to lose 30-43 and values help drive preferences for forested landscapes and million forest acres to urbanization between 1997 and 2060 forest-based benefits such as diversity and identity, justice, (Wear and Greis 2002), and structural changes in southeastern education, freedom, and spirituality (Farber and others 2002, ecosystems are expected to impact the provision of a wide Fisher and others 2009, Kellert 1996). Environmental policies range of cultural ecosystem service benefits (Bowker and others and responsible forest management can enhance how forests 2013). Concurrently, social trends also suggest that youth are help give rise to and support cultural ecosystem service values. -

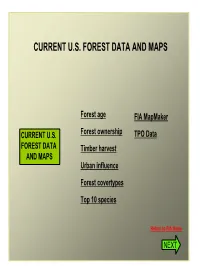

Current U.S. Forest Data and Maps

CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA AND MAPS Forest age FIA MapMaker CURRENT U.S. Forest ownership TPO Data FOREST DATA Timber harvest AND MAPS Urban influence Forest covertypes Top 10 species Return to FIA Home Return to FIA Home NEXT Productive unreserved forest area CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA (timberland) in the U.S. by region and AND MAPS stand age class, 2002 Return 120 Forests in the 100 South, where timber production West is highest, have 80 s the lowest average age. 60 Northern forests, predominantly Million acreMillion South hardwoods, are 40 of slightly older in average age and 20 Western forests have the largest North concentration of 0 older stands. 1-19 20-39 40-59 60-79 80-99 100- 120- 140- 160- 200- 240- 280- 320- 400+ 119 139 159 199 240 279 319 399 Stand-age Class (years) Return to FIA Home Source: National Report on Forest Resources NEXT CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA Forest ownership AND MAPS Return Eastern forests are predominantly private and western forests are predominantly public. Industrial forests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. Timber harvest by county FOREST DATA AND MAPS Return Timber harvests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. The South is the largest timber producing region in the country accounting for nearly 62% of all U.S. timber harvest. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. -

FOREST BIODIVERSITY Earth’S Living Treasure

OLOGIC OR BI AL DI Y F VER DA SI L TY A 2 N 2 IO M T a A y N 2 R 0 E 1 T 1 N I FOREST BIODIVERSITY Earth’s Living Treasure INTERNATIONAL DAY FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY 22 May 2011 FOREST BIODIVERSITY Earth’s Living Treasure Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. ISBN: 92-9225-298-4 Copyright © 2010, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Convention on Biological Diversity. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that use this document as a source. Citation: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2010). Forest Biodiversity—Earth’s Living Treasure. Montreal, 48 pages. For further information, please contact: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity World Trade Centre 413 St. Jacques Street, Suite 800 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2Y 1N9 Phone: 1 (514) 288 2220 Fax: 1 (514) 288 6588 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cbd.int Design & typesetting: Em Dash Design Cover illustration: Cover illustration: Untitled, 2010. -

E666134Z Enhance Development of the Forest Understory to Create

CONSERVATION ENHANCEMENT ACTIVITY E666134Z Enhance development of the forest understory to create conditions resistant to pests Conservation Practice 666: Forest Stand Improvement APPLICABLE LAND USE: Forest RESOURCE CONCERN ADDRESSED: Degraded Plant Condition PRACTICE LIFE SPAN: 10 Years Enhancement Description: Forest stand improvement that manages the structure and composition of overstory and understory vegetation to reduce vulnerability to damage by insects and diseases of forest trees. Managing the understory vegetation will also reduce the risk of wildfire, and promote development of herbaceous plants that benefit wildlife. This enhancement provides for management of the understory vegetation in a forested area, using mechanical, chemical or manual methods to improve the plant species mix and the health of the residual vegetation. These practices encourage the development of a less dense forested ecosystem. The canopy gaps and open understory allow for air circulation that reduces the incidence of disease, and the improved health of the residual trees increases their ability to withstand insect attacks. Forest stand improvement (FSI) activities are used to remove trees of undesirable species, form, quality, condition, or growth rate. The quantity and quality of forest for wildlife and/or timber production will be increased by manipulating stand density and structure. These treatments can also reduce wildfire hazards, improve forest health, restore natural plant communities, and achieve or maintain a desired native understory plant community for soil health, wildlife, grazing, and/or browsing. Criteria: States will apply general criteria from the NRCS National Conservation Practice Standard (CPS) 666 as listed below, and additional criteria as required by the NRCS State Office. The enhancement will be applied to sites which have an uncharacteristically dense understory of shrubs and small trees that limit development of ground cover. -

Non-Timber Forest Products in Brazil: a Bibliometric and a State of the Art Review

sustainability Review Non-Timber Forest Products in Brazil: A Bibliometric and a State of the Art Review Thiago Cardoso Silva * , Emmanoella Costa Guaraná Araujo, Tarcila Rosa da Silva Lins , Cibelle Amaral Reis, Carlos Roberto Sanquetta and Márcio Pereira da Rocha Department of Forestry Engineering and Technology, Federal University of Paraná, 80.210-170 Curitiba, Brazil; [email protected] (E.C.G.A.); [email protected] (T.R.d.S.L.); [email protected] (C.A.R.); [email protected] (C.R.S.); [email protected] (M.P.d.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-8199-956-6178 Received: 4 July 2020; Accepted: 22 August 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are a consolidated source of income and acquisition of inputs from forest environments. Therefore, the objective of this work was to carry out a collection of publications on NTFPs in Brazil, until 2019, available in the Scopus database, presenting a bibliometric review and the state of the art of this theme from the evaluation of these publications, discussing the challenges of Brazilian legislation on NTFPs. After screening the articles of interest, 196 documents were evaluated, in which they were observed institutions and authors, analyzing networks of citations and terms used, areas of forest sciences and sciences that encompass the most explored biomes and the most studied species. The results showed that the concern to research on NTFPs in Brazil began in the 1990s, with an increase in the number of publications over the years. Besides that, the research on NTFPs is multidisciplinary, with emphasis on the areas of Agricultural and Biological Sciences and Environmental Science. -

OUR FORESTS and JUNGLES © Sarah Walsh / Silverback Films Netflix

OUR FORESTS AND JUNGLES © Sarah Walsh / Silverback Films Netflix Walsh © Sarah Forests and jungles touch our lives every day. They have done for millions of years, since the world’s first peoples used them to get shelter, food, water, and firewood. Today, 300 million people still live in forests and over one Forests are naturally resilient, and areas cleared of tree billion people depend on them for their livelihood. Forests cover can spring back to life if given a chance, even after cover almost one third of our planet’s land area and well huge forest fires. In fact, natural fires started by lightning over half of the species found on land live in forests. may seem to be a terrible thing for forests, but actually often allows them to grow back stronger and to support a There are many kinds of forest on our planet, but they all bigger variety of animals and plants than if the trees just contain a delicate balance of plants, animals, fungi and kept growing. Some pine trees are adapted to frequent bacteria. Forests provide us with many resources, including fires, and have cones that only open to release seeds in food, paper, building materials, chocolate, medicines, and the heat of a fierce fire. The ash after a fire is filled with even the air we breathe. Forests make rainfall and filter nutrients and perfect for new plants and trees to grow in freshwater. Most importantly, they are the lungs of our the space left by the trees that have burned to the ground.