A Community Psychologist's Perspective on Domestic Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Psychology Newsletter

Community Psychology Newsletter November 2015 DR. TIM AUBRY, DR. BRUCE TEFFT , AND DR. GEOFF NELSON IN THIS ISSUE Reflections on Community Psychology by Dr. Bruce Tefft “In the last analysis, politics is not community psychology but society as a predictions and politics is not whole. observations. Politics is what we do, what we create, what we work for, what we Overall, I am more excited and hope for, and what we dare to imagine.” optimistic about the future of Paul Wellstone (University community psychology in Canada than I An interview with Dr. Geoff Nelson professor and former US have ever been. For decades community “Community psychology is a value- Senator) psychology has remained true to its based field, and its values are congruent founding values, beliefs, and objectives, with my personal values of social such as social and economic justice. On the occasion of my impending inclusion, social justice, power-sharing, However, until relatively recently, it retirement after 40 years as a university- and collaboration. I feel very fortunate seemed that as community based teacher, researcher, and that I have a job, where my work lines up psychologists we were beating our practitioner of community psychology in with my values.” Page 3 Canada, I have the privilege of being collective heads against a very hard brick given the opportunity to reflect on the wall when it came to convincing policy An interview with Rebecca Cherner changes I have observed in the field over makers that there was indeed a better “From my mentors, I have learned the that period of time, as well as the future way to expend public resources and help importance of engaging with people prospects for community psychology. -

Prescriptive Authority

5/30/2017 Prescriptive Authority: Psychologist Prescribing Why are we here? Rights: Allowing Prescribing Rights For The Latest on Legislation and Psychologists Is An Essential Step Training To Providing Thousands Of Patients With Access To Comprehensive Mental Health Care John Gavazzi, Psy.D., ABPP Tracy E. Ransom, Psy.D. Learning Objectives: 1. Describe benefits & challenges of RxP; 2. List the states that have RxP & psychologist experiences in these locations; 3. Discuss PA legislative affairs related to RxP; 4. Describe training program requirements for RxP; 5. Analyze the prescribing rights initiative through group discussion Why is RxP even a thing? Ethical aspects of RxP • Fewer psychiatrists and physicians • Beneficence across the country • Access to high quality mental • Fewer psychiatrists in rural and urban health care areas • Integration of physical and • Fewer psychiatrists take insurance psychological aspects to care: lower cost/convenience 1 5/30/2017 Some Themes to Ponder General thoughts • Organized medicine is not our enemy. • Skills Before Pills Why? • The authority to prescribe gives you the • Need to unify our organization. Why? authority to take meds away and use psychological interventions • Need a great deal of work with grassroots organizations, such as law enforcement • Psychology is the best medicine and community mental health. Why? • Psychologists are the best trained to • This will be a long-term, time consuming integrate a biopsychosocial approach. operation At a Glance Where Can Psychologists prescribe? RxP will be considered a specialty practice, in which a masters degree in psychopharmacology will be needed Louisiana Idaho Over 20 years prescribing in the military, 10+ years in New Mexico, and 10+ years in Louisiana New Mexico Indian Health Services Allowing prescribing rights for psychologists is an Illinois essential step to providing thousands of patients All Branches of the US with access to comprehensive mental health Military care. -

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Stroke Rehabilitation

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Stroke Rehabilitation Amy Quilty OT Reg. (Ont.), Occupational Therapist Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Certificate Program, University of Toronto Quinte Health Care: [email protected] Learning Objectives • To understand that CBT: • has common ground with neuroscience • principles are consistent with stroke best practices • treats barriers to stroke recovery • is an opportunity to optimize stroke recovery Question? Why do humans dominate Earth? The power of THOUGHT • Adaptive • Functional behaviours • Health and well-being • Maladaptive • Dysfunctional behaviours • Emotional difficulties Emotional difficulties post-stroke • “PSD is a common sequelae of stroke. The occurrence of PSD has been reported as high as 30–60% of patients who have experienced a stroke within the first year after onset” Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Mood, Cognition and Fatigue Following Stroke practice guidelines, update 2015 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijs.12557/full • Australian rates: (Kneeborne, 2015) • Depression ~31% • Anxiety ~18% - 25% • Post Traumatic Stress ~10% - 30% • Emotional difficulties post-stroke have a negative impact on rehabilitation outcomes. Emotional difficulties post-stroke: PSD • Post stroke depression (PSD) is associated with: • Increased utilization of hospital services • Reduced participation in rehabilitation • Maladaptive thoughts • Increased physical impairment • Increased mortality Negative thoughts & depression • Negative thought associated with depression has been linked to greater mortality at 12-24 months post-stroke Nursing Best Practice Guideline from RNAO Stroke Assessment Across the Continuum of Care June : http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao- ca/files/Stroke_with_merged_supplement_sticker_2012.pdf Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ViaCs0k2jM Cognitive Behavioral Therapy - CBT A Framework to Support CBT for Emotional Disorder After Stroke* *Figure 2, Framework for CBT after stroke. -

The EAT-16: Validation of a Shortened Form of the Eating Attitudes Test Elizabeth Mclaughlin

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Psychology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 The EAT-16: Validation of a Shortened Form of the Eating Attitudes Test Elizabeth McLaughlin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/psy_etds Recommended Citation McLaughlin, Elizabeth. "The EAT-16: Validation of a Shortened Form of the Eating Attitudes Test." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/psy_etds/94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Elizabeth McLaughlin Candidate Psychology Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Dr. Jane Ellen Smith, Chairperson Dr. Sarah Erickson Dr. Katie Witkiewitz ii THE EAT-16: VALIDATION OF A SHORTENED FORM OF THE EATING ATTITUDES TEST by ELIZABETH MCLAUGHLIN BACHELOR OF ARTS THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Psychology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2014 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’m grateful to my committee, whose guidance and direction were indispensable: Dr. Katie Witkiewitz, Dr. Sarah Erickson, and of course Dr. Jane Smith. I could imagine no better advisor than Jane to work with on this project! And I’m thankful for the encouragement I received from friends and family, both close by and far away. To my parents and my sister, Lydia: your belief in me, and your help in maintaining perspective, did so much more than you realize to carry me through the master’s process. -

510.469.7777 [email protected] M

510.469.7777 [email protected] M. PALOMA PAVEL, Ph.D., M.Div Teaching, Counseling, Program Administration and Curriculum Development EDUCATION Ph.D. California School of Professional Psychology, Berkeley (APA Accredited) Organizational and Clinical Psychology Dissertation research published with Carnegie Foundation, Good Work: The Future of the Academic Workplace in America M.Div. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA ( cum laude ) B.A. University of Southern California, Los Angeles ( summa cum laude ) International Relations and Religious Studies Post-Grad London School of Economics, International Relations and Peace Research Licensure Licensed issued to practice as Psychologist in California (1993) CAPABILITIES Psychology Professor Curriculum Development Social Media Models Student Advisor Keynote Speaker Student Internships Clinical Counselor Social Justice & Psychology Build Teaching Models PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Visiting and Adjunct Faculty in Psychology and Program Consultant, CA 2008 to Present Ford Foundation, New York NY: Director of Strategic Communications 2000 to 2008 Earth House Center, Founder/President/Consultant, Oakland, CA 1990 to 2016 California Institute of Integral Studies, Associate Prof., SF, CA 1989 to 1997 ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Pacifica Graduate Institute, Santa Barbara CA : Visiting Faculty in Community Psychology, Liberation Psychology and Eco-psychology Program. Doctoral courses taught: Community Mobilization and Policy Development; Community Counseling and Advocacy. Guided 15 student dissertations. University of California, Davis : Visiting Faculty and Consultant to the Regional Advisory Committee (RAC), strategic planning for the Center for Regional Change, including curriculum development and development of civic engagement strategies. California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco CA : Associate Professor and Department Chair of Organizational Development and Social Transformation Program. Program Adjunct Professor of Women’s Spirituality. -

Student Handbook for the Ph.D

PH.D. PROGRAM IN CLINICAL-COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY WITH RURAL INDIGENOUS EMPHASIS OFFERED JOINTLY BY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS AND THE UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE HTTP://PSYPHD.ALASKA.EDU UAF Program Director UAA Program Director Valerie Gifford James Fitterling Assistant Professor Associate Professor School of Education Department of Psychology Counseling Program University of Alaska Anchorage University of Alaska Fairbanks 907-786.1580; [email protected] 907-474-7631; [email protected] UAF Program Coordinator UAA Program Coordinator Angela Mitchell Anissa Hauser UAF Program Coordinator UAA Program Coordinator P.O. Box 756480 3211 Providence Drive Fairbanks, AK 99775 Anchorage, AK 99508 (907) 474-7012; [email protected] (907) 786-1640; [email protected] The UAA-UAF Ph.D. Program in Clinical-Community Psychology is accredited as a clinical psychology program by the American Psychological Association*. Questions related to the program’s accredited status should be directed to the Commission on Accreditation: Office of Program Consultation and Accreditation American Psychological Association 750 1st Street, NE Washington, DC 20002 Phone: (202) 336-5979 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apa.org/ed/accreditation Ph.D. Program in Clinical-Community Psychology Handbook for AY 2016-2017 STUDENT HANDBOOK FOR THE PH.D. PROGRAM IN CLINICAL-COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY WITH RURAL INDIGENOUS EMPHASIS Offered Jointly by the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the University of Alaska Anchorage TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE: BASICS -

Clinical Versus Counseling Psychology: What's the Diff? by John C

Clinical Versus Counseling Psychology: What's the Diff? by John C. Norcross - University of Scranton, Fields of Psychology Graduate School The majority of psychology students applying to graduate school are interested in clinical work, and approximately half of all graduate degrees in psychology are awarded in the subfields of clinical and counseling psychology (Mayne, Norcross, & Sayette, 2000). But deciding on a health care specialization in psychology gets complicated. The urgent question facing each student--and the question frequently posed to academic advisors--is "What are the differences between clinical psychology and counseling psychology?" Or, as I am asked in graduate school workshops, "What's the diff?" This article seeks to summarize the considerable similarities and salient differences between these two psychology subfields on the basis of several recent research studies. The results can facilitate your informed choice in the application process, enhance matching between the specialization and your interests, and sharpen the respective identities of psychology training programs. Considerable Similarities The distinctions between clinical psychology and counseling psychology have steadily faded in recent years, leading many to recommend a merger of the two. Graduates of doctoral- level clinical and counseling psychology programs are generally eligible for the same professional benefits, such as psychology licensure, independent practice, and insurance reimbursement. The American Psychological Association (APA) ceased distinguishing -

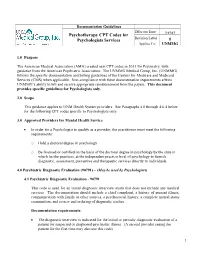

Psychotherapy CPT Codes for Psychologists Services

Documentation Guidelines Effective Date Psychotherapy CPT Codes for 7/17/17 Psychologists Services Revision Letter B Applies To: UNMMG 1.0 Purpose The American Medical Association (AMA) created new CPT codes in 2013 for Psychiatry, with guidance from the American Psychiatric Association. The UNMMG Medical Group, Inc. (UNMMG) follows the specific documentation and billing guidelines of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) when applicable. Non-compliance with these documentation requirements affects UNMMG’s ability to bill and receive appropriate reimbursement from the payers. This document provides specific guidelines for Psychologists only. 2.0 Scope This guidance applies to UNM Health System providers. See Paragraphs 4.0 through 4.6.4 below for the following CPT codes specific to Psychologists only. 3.0 Approved Providers for Mental Health Service In order for a Psychologist to qualify as a provider, the practitioner must meet the following requirements: o Hold a doctoral degree in psychology o Be licensed or certified on the basis of the doctoral degree in psychology by the state in which he/she practices, at the independent practice level of psychology to furnish diagnostic, assessment, preventive and therapeutic services directly to individuals. 4.0 Psychiatric Diagnostic Evaluation (90791) – (May be used by Psychologists) 4.1 Psychiatric Diagnostic Evaluation - 90791 This code is used for an initial diagnostic interview exam that does not include any medical services. The documentation should include a chief complaint, a history of present illness, communication with family or other sources, a psychosocial history, a complete mental status examination, and review and ordering of diagnostic studies. -

1 from Viktor Frankl's Logotherapy to the Four Defining Characteristics of Self-Transcendence (ST) Paul T. P. Wong Introductio

1 From Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy to the Four Defining Characteristics of Self-Transcendence (ST) Paul T. P. Wong Introduction The present paper continues my earlier presentation on self-transcendence (ST) as a pathway to meaning, virtue, and happiness (Wong, 2016), in which I introduced Viktor Frankl’s (1985) two-factor theory of ST. Here, the same topic of ST is expanded by first providing the basic assumptions of logotherapy, then arguing the need for objective standards for meaning, and finally elaborating the defining characteristics of ST. To begin, here is a common-sense observation—no one can remain at the same spot for life for a variety of reasons, such as developmental and environmental changes, but most importantly because people dream of a better life and want to move to a preferred destination where they can find happiness and fulfillment. As a psychologist, I am interested in finding out (a) which destination people choose and (b) how they plan to get there successfully. In a free society that offers many opportunities for individuals, there are almost endless options regarding both (a) and (b). The reality is that not all purposes in life are equal. Some life goals are misguided, such as wanting to get rich by any means, including unethical and illegal ones, because ultimately, such choices could be self-defeating—these end values might not only fail to fill their hearts with happiness, but might also ruin their relationships and careers. The question, then, is: What kind of choices will have the greatest likelihood of resulting in a good life that not only benefits the individual but also society? My research has led me to hypothesize that the path of ST is most likely to result in such a good life. -

Emotion in Psychotherapy

Emotion in Psychotherapy Leslie S. Greenberg York University Jeremy D. Safran Clarke Institute of Psychiatry ABSTRACT." The therapeutic process involves many dif- psychotherapy field to develop an integrative and empir- ferent types of affective phenomena. No single therapeutic ically informed perspective on the role of emotion in perspective has been able to encompass within its own change. This will provide an orienting framework for in- theoretical framework all the ways in which emotion plays vestigating the diverse array of different emotional phe- a role in therapeutic change. A comprehensive, constructive nomena traditionally focused on by different therapy tra- theory of emotion helps transcend the differences in the ditions. therapeutic schools by viewing emotion as a complex syn- thesis of expressive motor, schematic, and conceptual in- Psychotherapeutic Approaches to Emotion formation that provides organisms with information about Psychotherapists have long concerned themselves with their responses to situations that helps them orient adap- working with people's emotional experience. Different tively in the environment. In addition to improved theory, theoretical perspectives have tended to emphasize differ- increased precision in the assessment of affective func- ent aspects of emotional functioning. As a result, the psy- tioning in therapy, as well as greater specification of dif- chotherapy literature has failed to produce an integrative, ferent emotional change processes and means of facili- comprehensive perspective on emotion capable of illu- tating these, will allow the role of emotion in change to minating the full array of emotional phenomena relevant be studied more effectively. A number of different change to psychotherapy. In this section, we will briefly highlight processes involving emotion are discussed, as well as some of the important themes characterizing three of the principles of emotionally focused intervention that help major therapeutic perspectives on emotion: psychoanal- access emotion and promote emotional restructuring. -

Historical Background

MM01_MORI5627_05_SE_C01.indd01_MORI5627_05_SE_C01.indd PagePage 1 30/05/1330/05/13 //203/PH01348/9780205255627_MORITSUGU/MORITSUGU_COMMUNITY_PSYCHOLOGY5_SE_9780205 27:0070:030/P AMAHM01 user-f-401u3s4e8r/-9f-7480012 05255627_MORITSUGU/MORITSUGU_COMMUNITY_PSYCHOLOGY5_SE_978020525 ... 1 Introduction: Historical Background HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ▪ CASE IN POINT 1.2 Does Primary Social Movements Prevention Work? Swampscott Social Justice WHAT IS COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY? Emphasis on Strengths and Competencies Social Change and Action Research FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES Interdisciplinary Perspectives A Respect for Diversity ▪ CASE IN POINT 1.3 Social Psychology, The Importance of Context and Environment Community Psychology, and Homelessness Empowerment ▪ CASE IN POINT 1.4 The Importance The Ecological Perspective/Multiple Levels of of Place Intervention ▪ A Psychological Sense of Community CASE IN POINT 1.1 Clinical Psychology, Training in Community Psychology Community Psychology: What’s the Difference? PLAN OF THE TEXT OTHER CENTRAL CONCEPTS Prevention Rather Than Therapy SUMMARY Until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. —Martin Luther King, quoting Amos 5:24 Be the change that you wish to see in the world. —M. Gandhi 1 MM01_MORI5627_05_SE_C01.indd01_MORI5627_05_SE_C01.indd PagePage 2 30/05/1330/05/13 //203/PH01348/9780205255627_MORITSUGU/MORITSUGU_COMMUNITY_PSYCHOLOGY5_SE_9780205 27:0070:030/P AMAHM01 user-f-401u3s4e8r/-9f-7480012 05255627_MORITSUGU/MORITSUGU_COMMUNITY_PSYCHOLOGY5_SE_978020525 ... 2 Part I • Introductory Concepts My dog Zeke is a big, friendly Lab–golden retriever–Malamute mix. Weighing in at a little over 100 pounds, he can be intimidating when you first see him. Those who come to know him find a puppy-like enthusi- asm and an eagerness to please those he knows. One day, Zeke got out of the backyard. He scared off the mail delivery person and roamed the streets around our home for an afternoon. -

Community Psychology Erika Sanborne, 2002

A Value Framework for Community Psychology Erika Sanborne, 2002 INTRODUCTION “Community Psychology concerns the relationships of the individual to communities and society. Through collaborative research and action, community psychologists seek to understand and to enhance quality of life for individuals, communities, and society” (Dalton, Elias & Wandersman, 2001, p. 5). The work of community psychology is best understood in terms of the complementary core values that guide our reactions to, and interactions with others. To understand the possible roles of a community psychologist is to understand the underlying principles that govern how we approach a situation. The following us a discussion of key concepts integral to community psychology perspective. It is hoped that in reading the overview, the reader will gain an appreciation for the field of community psychology and for the valuable roles a community psychologist might play in our world. PREVENTION Rather than just reacting to a problem or issue and finding means with which to treat it, the ideal approach would be to identify ways to minimize or prevent the problem from ever occurring. To do this we look at precipitating factors and hope to intervene in meaningful ways that change environmental and/or personal factors, and that remove barriers to success and wellness, before disorder develops. A popular metaphor is used to help visualize how prevention looks in process: Two men are walking along the river. One spots a drowning person floating by. The walker jumps in and grabs the drowning person and he pulls him safely from the water. Before catching his breath he sees that his friend has jumped in to save another drowning person.