The Study of Proto-Magnetar Winds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Dwarfs

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide White Dwarfs White dwarfs are among the dimmest stars in the universe. Even so, they have commanded the attention of astronomers ever since the first white dwarf was observed by optical telescopes in the middle of the 19th century. One reason for this interest is that white dwarfs represent an intriguing state of matter; another reason is that most stars, including our sun, will become white dwarfs when they reach their final, burnt-out collapsed state. A star experiences an energy crisis and its core collapses when the star's basic, non-renewable energy source - hydrogen - is used up. A shell of hydrogen on the edge of the collapsed core will be compressed and heated. The nuclear fusion of the hydrogen in the shell will produce a new surge of power that will cause the outer layers of the star to expand until it has a diameter a hundred times its present value. This is called the "red giant" phase of a star's existence. A hundred million years after the red giant phase all of the star's available energy resources will be used up. The exhausted red giant will puff off its outer layer leaving behind a hot core. This hot core is called a Wolf-Rayet type star after the astronomers who first identified these objects. This star has a surface temperature of about 50,000 degrees Celsius and is A composite furiously boiling off its outer layers in a "fast" wind traveling 6 million image of the kilometers per hour. -

The Evolution of Helium White Dwarfs: Applications to Millisecond

Pulsar Astronomy — 2000 and Beyond ASP Conference Series, Vol. 3 × 108, 1999 M. Kramer, N. Wex, and R. Wielebinski, eds. The evolution of helium white dwarfs: Applications for millisecond pulsars T. Driebe and T. Bl¨ocker Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany D. Sch¨onberner Astrophysikalisches Institut Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany 1. White Dwarf Evolution Low-mass white dwarfs with helium cores (He-WDs) are known to result from mass loss and/or exchange events in binary systems where the donor is a low mass star evolving along the red giant branch (RGB). Therefore, He-WDs are common components in binary systems with either two white dwarfs or with a white dwarf and a millisecond pulsar (MSP). If the cooling behaviour of He- WDs is known from theoretical studies (see Driebe et al. 1998, and references therein) the ages of MSP systems can be calculated independently of the pulsar properties provided the He-WD mass is known from spectroscopy. Driebe et al. (1998, 1999) investigated the evolution of He-WDs in the mass range 0.18 < MWD/M⊙ < 0.45 using the code of Bl¨ocker (1995). The evolution of a 1 M⊙-model was calculated up to the tip of the RGB. High mass loss termi- nated the RGB evolution at appropriate positions depending on the desired final white dwarf mass. When the model started to leave the RGB, mass loss was virtually switched off and the models evolved towards the white dwarf cooling branch. The applied procedure mimicks the mass transfer in binary systems. Contrary to the more massive C/O-WDs (MWD ∼> 0.5 M⊙, carbon/oxygen core), whose progenitors have also evolved through the asymptotic giant branch phase, He-WDs can continue to burn hydrogen via the pp cycle along the cooling branch arXiv:astro-ph/9910230v1 13 Oct 1999 down to very low effective temperatures, resulting in cooling ages of the order of Gyr, i. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

Chapter 16 the Sun and Stars

Chapter 16 The Sun and Stars Stargazing is an awe-inspiring way to enjoy the night sky, but humans can learn only so much about stars from our position on Earth. The Hubble Space Telescope is a school-bus-size telescope that orbits Earth every 97 minutes at an altitude of 353 miles and a speed of about 17,500 miles per hour. The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) transmits images and data from space to computers on Earth. In fact, HST sends enough data back to Earth each week to fill 3,600 feet of books on a shelf. Scientists store the data on special disks. In January 2006, HST captured images of the Orion Nebula, a huge area where stars are being formed. HST’s detailed images revealed over 3,000 stars that were never seen before. Information from the Hubble will help scientists understand more about how stars form. In this chapter, you will learn all about the star of our solar system, the sun, and about the characteristics of other stars. 1. Why do stars shine? 2. What kinds of stars are there? 3. How are stars formed, and do any other stars have planets? 16.1 The Sun and the Stars What are stars? Where did they come from? How long do they last? During most of the star - an enormous hot ball of gas day, we see only one star, the sun, which is 150 million kilometers away. On a clear held together by gravity which night, about 6,000 stars can be seen without a telescope. -

The Deaths of Stars

The Deaths of Stars 1 Guiding Questions 1. What kinds of nuclear reactions occur within a star like the Sun as it ages? 2. Where did the carbon atoms in our bodies come from? 3. What is a planetary nebula, and what does it have to do with planets? 4. What is a white dwarf star? 5. Why do high-mass stars go through more evolutionary stages than low-mass stars? 6. What happens within a high-mass star to turn it into a supernova? 7. Why was SN 1987A an unusual supernova? 8. What was learned by detecting neutrinos from SN 1987A? 9. How can a white dwarf star give rise to a type of supernova? 10.What remains after a supernova explosion? 2 Pathways of Stellar Evolution GOOD TO KNOW 3 Low-mass stars go through two distinct red-giant stages • A low-mass star becomes – a red giant when shell hydrogen fusion begins – a horizontal-branch star when core helium fusion begins – an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star when the helium in the core is exhausted and shell helium fusion begins 4 5 6 7 Bringing the products of nuclear fusion to a giant star’s surface • As a low-mass star ages, convection occurs over a larger portion of its volume • This takes heavy elements formed in the star’s interior and distributes them throughout the star 8 9 Low-mass stars die by gently ejecting their outer layers, creating planetary nebulae • Helium shell flashes in an old, low-mass star produce thermal pulses during which more than half the star’s mass may be ejected into space • This exposes the hot carbon-oxygen core of the star • Ultraviolet radiation from the exposed -

Pulsating Red Giant Stars in Eccentric Binary Systems Discovered from Kepler Space-Based Photometry a Sample Study and the Analysis of KIC 5006817 P

A&A 564, A36 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322477 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Pulsating red giant stars in eccentric binary systems discovered from Kepler space-based photometry A sample study and the analysis of KIC 5006817 P. G. Beck1,K.Hambleton2,1,J.Vos1, T. Kallinger3, S. Bloemen1, A. Tkachenko1, R. A. García4, R. H. Østensen1, C. Aerts1,5,D.W.Kurtz2, J. De Ridder1,S.Hekker6, K. Pavlovski7, S. Mathur8,K.DeSmedt1, A. Derekas9, E. Corsaro1, B. Mosser10,H.VanWinckel1,D.Huber11, P. Degroote1,G.R.Davies12,A.Prša13, J. Debosscher1, Y. Elsworth12,P.Nemeth1, L. Siess14,V.S.Schmid1,P.I.Pápics1,B.L.deVries1, A. J. van Marle1, P. Marcos-Arenal1, and A. Lobel15 1 Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, KU Leuven, 3001 Leuven, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] 2 Jeremiah Horrocks Institute, University of Central Lancashire, Preston PR1 2HE, UK 3 Institut für Astronomie der Universität Wien, Türkenschanzstr. 17, 1180 Wien, Austria 4 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM-CNRS – Université Denis Diderot-IRFU/SAp, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France 5 Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, University of Nijmegen, PO Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands 6 Astronomical Institute Anton Pannekoek, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098 XH Amsterdam, The Netherlands 7 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 8 Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut street Suite #205, Boulder CO 80301, USA 9 Konkoly Observ., Research Centre f. Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1121 Budapest, Hungary 10 LESIA, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Denis Diderot, Observatoire de Paris, 92195 Meudon Cedex, France 11 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field CA 94035, USA 12 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgebaston, Birmingham B13 2TT, UK 13 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Villanova University, 800 East Lancaster avenue, Villanova PA 19085, USA 14 Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Univ. -

EVOLVED STARS a Vision of the Future Astron

PUBLISHED: 04 JANUARY 2017 | VOLUME: 1 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 0021 research highlights EVOLVED STARS A vision of the future Astron. Astrophys. 596, A92 (2016) Loop Plume A B EDPS A nearby red giant star potentially hosts a planet with a mass of up to 12 times that of Jupiter. L2 Puppis, a solar analogue five billion years more evolved than the Sun, could give a hint to the future of the Solar System’s planets. Using ALMA, Pierre Kervella has observed L2 Puppis in molecular lines and continuum emission, finding a secondary source that is roughly 2 au away from the primary. This secondary source could be a giant planet or, alternatively, a brown dwarf as massive as 28 Jupiter masses. Further observations in ALMA bands 9 or 10 (λ ≈ 0.3–0.5 mm) can help to constrain the companion’s mass. If confirmed as a planet, it would be the first planet around an asymptotic giant branch star. L2 Puppis (A in the figure) is encircled by an edge-on circumstellar dust disk (inner disk shown in blue; surrounding dust in orange), which raises the question of whether the companion body is pre-existing, or if it has formed recently due to accretion processes within the disk. If pre-existing, the putative planet would have had an orbit similar in extent to that of Mars. Evolutionary models show that eventually this planet will be pulled inside the convective envelope of L2 Puppis by tidal forces. The companion’s interaction with the star’s circumstellar disk has invoked pronounced features above the disk: an extended loop of warm dusty material, and a visible plume, potentially launched by accretion onto a disk of material around the planet itself (B in the figure). -

Jsolated Stars of Low Metallicity

galaxies Article Jsolated Stars of Low Metallicity Efrat Sabach Department of Physics, Technion—Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel; [email protected] Received: 15 July 2018; Accepted: 9 August 2018; Published: 15 August 2018 Abstract: We study the effects of a reduced mass-loss rate on the evolution of low metallicity Jsolated stars, following our earlier classification for angular momentum (J) isolated stars. By using the stellar evolution code MESA we study the evolution with different mass-loss rate efficiencies for stars with low metallicities of Z = 0.001 and Z = 0.004, and compare with the evolution with solar metallicity, Z = 0.02. We further study the possibility for late asymptomatic giant branch (AGB)—planet interaction and its possible effects on the properties of the planetary nebula (PN). We find for all metallicities that only with a reduced mass-loss rate an interaction with a low mass companion might take place during the AGB phase of the star. The interaction will most likely shape an elliptical PN. The maximum post-AGB luminosities obtained, both for solar metallicity and low metallicities, reach high values corresponding to the enigmatic finding of the PN luminosity function. Keywords: late stage stellar evolution; planetary nebulae; binarity; stellar evolution 1. Introduction Jsolated stars are stars that do not gain much angular momentum along their post main sequence evolution from a companion, either stellar or substellar, thus resulting with a lower mass-loss rate compared to non-Jsolated stars [1]. As previously stated in Sabach and Soker [1,2], the fitting formulae of the mass-loss rates for red giant branch (RGB) and asymptotic giant branch (AGB) single stars are set empirically by contaminated samples of stars that are classified as “single stars” but underwent an interaction with a companion early on, increasing the mass-loss rate to the observed rates. -

Evolution of Thermally Pulsing Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars

The Astrophysical Journal, 822:73 (15pp), 2016 May 10 doi:10.3847/0004-637X/822/2/73 © 2016. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. EVOLUTION OF THERMALLY PULSING ASYMPTOTIC GIANT BRANCH STARS. V. CONSTRAINING THE MASS LOSS AND LIFETIMES OF INTERMEDIATE-MASS, LOW-METALLICITY AGB STARS* Philip Rosenfield1,2,7, Paola Marigo2, Léo Girardi3, Julianne J. Dalcanton4, Alessandro Bressan5, Benjamin F. Williams4, and Andrew Dolphin6 1 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy G. Galilei, University of Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, I-35122 Padova, Italy 3 Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova—INAF, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, I-35122 Padova, Italy 4 Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, Box 351580, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 5 Astrophysics Sector, SISSA, Via Bonomea 265, I-34136 Trieste, Italy 6 Raytheon Company, 1151 East Hermans Road, Tucson, AZ 85756, USA Received 2016 January 1; accepted 2016 March 14; published 2016 May 6 ABSTRACT Thermally pulsing asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) stars are relatively short lived (less than a few Myr), yet their cool effective temperatures, high luminosities, efficient mass loss, and dust production can dramatically affect the chemical enrichment histories and the spectral energy distributions of their host galaxies. The ability to accurately model TP-AGB stars is critical to the interpretation of the integrated light of distant galaxies, especially in redder wavelengths. We continue previous efforts to constrain the evolution and lifetimes of TP-AGB stars by modeling their underlying stellar populations. Using Hubble Space Telescope (HST) optical and near-infrared photometry taken of 12 fields of 10 nearby galaxies imaged via the Advanced Camera for Surveys Nearby Galaxy Survey Treasury and the near-infrared HST/SNAP follow-up campaign, we compare the model and observed TP- AGB luminosity functions as well as the ratio of TP-AGB to red giant branch stars. -

Isotopic Imprints of Super-Agb Stars and Their Supernovae in the Solar System

82nd Annual Meeting of The Meteoritical Society 2019 (LPI Contrib. No. 2157) 6424.pdf ISOTOPIC IMPRINTS OF SUPER-AGB STARS AND THEIR SUPERNOVAE IN THE SOLAR SYSTEM. L. R. Nittler, Dept. of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 5241 Broad Branch Rd NW, Washington DC 20015, USA ([email protected]) Introduction: In studies of the origin of presolar grains and bulk nucleosynthetic isotopic anomalies in meteorites, little attention has been paid to the potential importance of stars in the mass range of ~8-10 solar masses. These stars lie in a middle-ground between low- and intermediate mass asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars that end their lives as white dwarfs and massive stars whose cores burn all the way to Fe before collapsing and exploding as supernovae (SNII), leaving behind neutron stars or black holes. They evolve through a “super-AGB” phase, undergoing thousands of thermal pulses and losing most of their mass in strong winds [1]. However, their final fates (e.g., as white dwarfs versus neutron stars following core-collapse supernovae) depend on highly uncertain physics and diagnostic observable signatures of both super-AGB stars and their possible supernovae are controversial [1, 2]. Here we discuss possible ways super-AGB stars and their supernovae may have left nucleosynthetic imprints in the solar system. Super-AGB stars: Although most presolar SiC, silicate and oxide stardust grains are inferred to have originated in AGB stars [3], the isotopic signatures largely point to relatively low-mass (~1-3 M) progenitors. Until recently, intermediate-mass (4-8M) AGB stars have largely been ruled out as parent stars because their predicted O isotopic ratios are not observed. -

The Coolest Brown Dwarfs

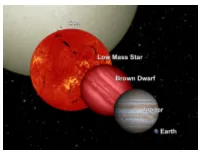

ClassY - The Coolest Brown Dwarfs CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3 – T9/Y0 - first class Y, 30 light-years distance, Temp 620K, Mass 15-30 M_Jup WISE 0855−0714 – Y2 - coolest at Temp ~ 250K, 7.3 light-years distance, Mass 3-10 M_Jup ClassY - The Coolest Brown Dwarfs CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3 – T9/Y0 - first class Y, 30 light-years distance, Temp 620K, Mass 15-30 M_Jup WISE 0855−0714 – Y2 - coolest at Temp ~ 250K, 7.3 light-years distance, Mass 3-10 M_Jup Why are all brown dwarf stars about the same size, even if the mass ranges from 10-500 M_Jup? Stellar evolution so far Different energy sources during different stages in the star's evolution Protostar phase (KH contraction) MS phase H->He RGB phase (shell H->He) And remember: more massive stars evolve faster during all stages What is this Plot Showing? globular cluster Announcements • Today – More low mass stellar evolution • Thursday – High mass stellar evolution and HW#4 is due • Tuesday Feb 25 – Review • Thursday Feb 27 – Exam#1 Intrinsic variability • Those that vary in brightness as a result of conditions within the star itself. • Found in the instability strip. Any star within these portions of the H-R diagram will become unstable to pulsations. • The different regions produce different kinds of observed phenomena. • Stars may go through these stages several times during their lives. Cause of pulsations • Stars are variable because they are unstable in one way or another: they lack hydrostatic equilibrium beneath surface. • Miras are not well understood, but other, more periodically varying stars are better understood, like the Cepheids: • The ionization zone of He lies at a distance from the center of the star, close to the surface. -

PS 224, Fall 2014 HW 4

PS 224, Fall 2014 HW 4 1. True or False? Explain in one or two short sentences. a. Scientists are currently building an infrared telescope designed to observe fusion reactions in the Sun’s core. False. Infrared telescopes cannot see through the Sun. b. Two stars that look very different must be made of different kinds of elements. False. What a star looks like depends on many different properties like mass, age, and size. c. Two stars that have the same apparent brightness in the sky must also have the same luminosity. False. How bright a star appears depends on the luminosity of a stars and its distance away from us. d. Some of the stars on the main sequence of the H-R diagram are not converting hydrogen into helium. False. The main-seuqence is defined as the phase of a star’s life when it burns hydrogen into helium. e. Stars that begin their lives with the most mass live longer than less massive stars because they have so much more hydrogen fuel. False. Massive stars live have shorter lifetimes as they burn through their fuel faster. f. All giants, supergiants, and white dwarfs were once main-sequence stars. True. Main-sequence stars evolve to become giants and supergiants based on their mass and eventually end up as white dwarfs. g. The iron in my blood came from a star that blew up more than 4 billion years ago. True. All elements except hydrogen and helium were produced in stars. h. If the Sun had been born 4½ billion years ago as a high-mass star rather than as a low- mass star, Jupiter would have Earth-like conditions today, while Earth would be hot like Venus.