Noah A. Winkeller*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

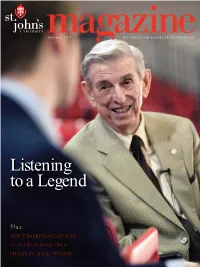

Listening to a Legend

Summer 2011 For Alumni and Friends of the University Listening to a Legend Plus: MEN'S BASKETBALL SENIORS 10 YEARS BARNES ARICO MULLIN TO HALL OF FAME first glance The Thrill Is Back It was a season of renewed excitement as the Red Storm men’s basketball team brought fans to their feet and returned St. John’s to a level of national prominence reminiscent of the glory days of old. Midway through the season, following thrilling victories over nationally ranked opponents, students began poking good natured fun at Head Coach Steve Lavin’s California roots by dubbing their cheering section ”Lavinwood.” president’s message Dear Friends, As you are all aware, St. John’s University is primarily an academic institution. We have a long tradition of providing quality education marked by the uniqueness of our Catholic, Vincentian and metropolitan mission. The past few months have served as a wonderful reminder, fan base this energized in quite some time. On behalf of each and however, that athletics are also an important part of the St. John’s every Red Storm fan, I’d like to thank the recently graduated seniors tradition, especially our storied men’s basketball program. from both the men’s and women’s teams for all their hard work and This issue of theSt. John’s University Magazine pays special determination. Their outstanding contributions, both on and off the attention to Red Storm basketball, highlighting our recent success court, were responsible for the Johnnies’ return to prominence and and looking back on our proud history. I hope you enjoy the profile reminded us of how special St. -

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

105484 Mbb Mg Cvr.Id2

STEVE PUIDOKAS RETIRED NUMBER Steve Puidokas burst upon the WSU basketball scene as a freshman in 1973-74, and by the time he left the Palouse, he had set five school records. He became the first basketball player and only the second student-athlete in WSU history to have his jersey number retired when he was honored Feb. 26, 1977. As a freshman, he averaged 16.8 points and 8.9 rebounds a game, earning All-District 8 honors, second team All- Pacific-8 recognition and third team All-West Coast accolades. He also became the first freshman selected to the Jayhawk and Rainbow Classic tournament teams. As a sophomore, Puidokas set school records with 42 points against Gonzaga and a 22.4 points per game season average. He led the Pacific-8 in scoring and was second in rebounding. He received an invitation to the Pan-American team tryouts and was a second team All-Pac-8 selection. During his junior campaign, Puidokas averaged 18.0 points and 10.6 rebounds per outing while garnering second team All-Pacific-8 honors for the third straight season. He became WSU’s all-time leading scorer that season. Puidokas capped his career at WSU by averaging 17.2 points and 9.7 rebounds during his senior season. He left WSU as the Cougars’ all-time leader with 1,894 points and 992 rebounds. He was named second team All-Pacific-8 for the fourth time, earned a second team All-West Coast selection and was a District 8 all-star. At the end of his career, he ranked fourth on the all-time Pac-8 list in scoring and seventh in rebounding. -

UCLA Men's Basketball Dec. 14, 2002 Marc Dellins/Bill Bennett/310-206

UCLA Men’s Basketball Dec. 14, 2002 Marc Dellins/Bill Bennett/310-206-8179 For Immediate Release IT'S FINALS WEEK FOR UCLA AS THE BRUINS HOST PORTLAND ON SATURDAY, DEC. 14 (5 P.M.) IN PAULEY PAVILION; UCLA WINS FIRST GAME OF SEASON ON DEC. 8 IN PAULEY, BEATING LONG BEACH STATE, 81-58 78.3(18-23) from the foul line, with 21 rebounds and 15 UPCOMING GAME turnovers. The 49ers were led by Tony Darden's 14 points. The Bruins lead the Long Beach State series 9-0. SATURDAY, DEC. 14 – UCLA (1-2) v s . Portland (3-2), 5 p.m., Pauley Pavilion. TV - UCLA-Portland Series – UCLA leads it 2-0. The Fox Sports Net West 2, with Bill Bruins have won both games in Pauley – 93-69 in 1967-68 Macdonald/Dan Belluomini; Radio – Fox Sports and 122-57 in 1966-67. AM 1150 – Chris Roberts/Don MacLean). UCLA TENTATIVE STARTING LINEUP (1-2) PORTLAND STARTING LINEUP (3-2) No. Name Pos. Ht. C l . Ppg Rpg No. Name Pos. Ht. Cl. Ppg Rpg 24 Jason Kapono F 6-8 Sr. 21.3 7.3 44 Dustin Geddis F 6-7 Jr. 8.0 6.0 43 T. J. Cummings C 6-10 Jr. 8.7 4.0 14 Ghislain Sema C 6-7 Jr. 7.6 5.2 45 Michael Fey C 7-0 Fr. 1.3 1.7 11 Eugene Geter G 5-10 Fr. 7.8 1.0 21 Cedric Bozeman G 6-6 So. 8.7 5.7 15 Adam Quick G 6-2 Jr. -

BASKETBALL ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS: 3204 Cullen Blvd

GAME 35 • NCAA TOURNAMENT MIDWEST REGION FIRST ROUND • vs. (14) GEORGIA STATE • 6:20 p.m. • MARCH 22, 2019 @UHCougarMBK UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON BASKETBALL ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS: 3204 Cullen Blvd. • Suite 2008 • Houston, TX • 77204 • Contact: Jeff Conrad ([email protected]) O: (713) 743-9410 | C: (713) 557-3841 | F: (713) 743-9411 • UHCougars.com #11/9 HOUSTON COUGARS (31-3 • 16-2 American) SETTING the SCENE Nov. 1 DALLAS BAPTIST (Ex.) W, 89-60 NCAA TOURNAMENT MIDWEST REGION FIRST ROUND Men Against Breast Cancer Cougar Cup #11/9 (3) HOUSTON COUGARS (31-3 • 16-2 American) Television: TBS Nov. 10 ALABAMA A&M (H&PE) ESPN3 W, 101-54 Brad Nessler (PxP) Nov. 14 RICE (H&PE) ESPN3 W, 79-68 vs. (14) GEORGIA STATE PANTHERS (24-9 • 13-5 SBC) Steve Lavin (analyst) Nov. 19 NORTHWESTERN STATE (H&PE) W, 82-55 Jim Jackson (analyst) Nov. 24 at BYU BYUtv W, 76-62 6:20 p.m. • Friday, March 22, 2019 Evan Washburn (reporter) Nov. 28 UT RIO GRANDE VALLEY (H&PE) W, 58-53 BOK Center (17,996) • Tulsa, Okla. Radio: 950 AM KPRC Inaugural Game in Fertitta Center (Houston) TBS• KPRC 950 AM Jeremy Branham (PxP) Dec. 1 #18/21 OREGON ESPN2 W, 65-61 Elvin Hayes (analyst) Dec. 4 LAMAR ESPN3 W, 79-56 COUGARS OPEN NCAA TOURNAMENT PLAY vs. GEORGIA STATE in TULSA Pregame show begins at 6:05 p.m. Dec. 8 at Oklahoma State FS Oklahoma W, 63-53 • For the second straight season and the 21st time in school history, the Cougars will Dec. -

Mega Conferences

Non-revenue sports Football, of course, provides the impetus for any conference realignment. In men's basketball, coaches will lose the built-in recruiting tool of playing near home during conference play and then at Madison Square Garden for the Big East Tournament. But what about the rest of the sports? Here's a look at the potential Missouri Pittsburgh Syracuse Nebraska Ohio State Northwestern Minnesota Michigan St. Wisconsin Purdue State Penn Michigan Iowa Indiana Illinois future of the non-revenue sports at Rutgers if it joins the Big Ten: BASEBALL Now: Under longtime head coach Fred Hill Sr., the Scarlet Knights made the Rutgers NCAA Tournament four times last decade. The Big East Conference’s national clout was hurt by the defection of Miami in 2004. The last conference team to make the College World Series was Louisville in 2007. After: Rutgers could emerge as the class of the conference. You find the best baseball either down South or out West. The power conferences are the ACC, Pac-10 and SEC. A Big Ten team has not made the CWS since Michigan in 1984. MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY Now: At the Big East championships in October, Rutgers finished 12th out of 14 teams. Syracuse won the Big East title and finished 14th at nationals. Four other Big East schools made the Top 25. After: The conferences are similar. Wisconsin won the conference title and took seventh at nationals. Two other schools made the Top 25. MEN’S GOLF Now: The Scarlet Knights have made the NCAA Tournament twice since 1983. -

University of San Diego Men's Basketball Media Guide 1992-1993

University of San Diego Digital USD Basketball (Men) University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides 1993 University of San Diego Men's Basketball Media Guide 1992-1993 University of San Diego Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-basketball-men UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO EROS '92-93 MEN'S BASKETBALL Senior Co-Captains Geoff Probst (#11) • Gylan Dottin (#24) RADIO AND TELEVISION ROSTER GEOFF ROCCO #11 PROBST #33 RAFFO 5' 11" 165 lbs. 6'9" 220 lbs. Senior Guard Freshman Center Corona de! Mar,CA Salinas, CA DAVID NEAL #13 FIZDALE #35 MEYER 6'2" 170 lbs. 6'3" 200 lbs. Freshman Guard Junior Guard Los Angeles, CA Scottsdale, AZ DOUG BRIAN HARRIS #21 #40 BRUSO 6'0" 174 lbs. 6'7" 200 lbs. Sophomore Guard Freshman Forward Chandler, AZ S. Lake Tahoe, CA----~~ JOE CHRISTOPHER #23 TEMPLE #44 GRANT 6'4" 208 lbs. 6' 8" 215 lbs. Junior Guard/Forward Junior Forward/Center San Diego, CA S. Lake Tahoe, CA GYLAN BROOKS #24 DOTTIN #50 BARNHARD 6'5" 220 lbs. 6'9" 220 lbs. Senior Forward Junior Center Santa Ana, CA Escondido, CA VAL RYAN #30 HILL #55 HICKMAN 6'4" 210 lbs. 6'6" 255 lbs. Freshman Guard/Forward Freshman Forward Tucson, AZ Los Angeles, CA SEAN #32 FLANNERY UNIVERSITY OF SA N DI EG O 6'7" 200 lbs. Freshman Guard :TOREROS Tucson, AZ CONTENTS Page I USD TORERO'S MESSAGE TO THE MEDIA The 1992-93 USD Basketball Media Guide was prepared and 1992-93 Basketball Yearbook edited by USD Sports Information Director Ted Gosen for use by & Media Guide media covering Torero basketball. -

Tim Jankovich – SMU Coaching U Live April 2017 (Dallas, Texas)

Tim Jankovich – SMU Coaching U Live April 2017 (Dallas, Texas) -When I was young I thought it was all about X’s & O’s and would laugh when I heard older coaches talk about culture. -Will study teams in the offseason to try and get ideas. Will watch clinic videos to try to spark ideas. -Game is so infinite. It’s one of the most exciting things about basketball to me. -We are all products of what we’ve been able to experience. I’ve had the fortune to work for a collection of 9 fantastic coaches. It’s not about copying a coach. It’s thinking about what makes him great. Lon Kruger (current Oklahoma head coach; Jankovich worked for him at UT-Pan American): • Not afraid to be simple offensively. Sometimes as coaches we feel like we have to manufacture every basket. • Coach was so competitive and so smart • My biggest takeaway was actually that there was more than one way to skin a cat. I had played for an old school guy in Jack Hartman and I thought that was the way to do it. Jack Hartman (former Kansas State head coach where Jankovich played and worked for him): • Base of knowledge Bob Weltich (former Texas head coach where Jankovich worked for him) • “Motion Offense” acumen (Weltich coached under Bob Knight at Army). Motion is truly glorious – five guys running around trying not get in the other guys’ way while still being purposeful. Boyd Grant (former Colorado State head coach where Jankovich worked for him) • Coach Grant won with less unlike anyone I’ve ever seen. -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A. -

Coaching Staff Coaching Staff Head Coach Lorenzo Romar

HuskiesCoaching Staff Coaching Staff Head Coach Lorenzo Romar Washington men’s ship and finish 31-2. Cameron Dollar, an assistant • Saint Louis won their first conference tourna- basketball coach coach on Romar’s Saint Louis and Washington ment championship in the program’s history. Lorenzo Romar was staffs, was one of the stars for the Bruins during named to head up that national title contest, replacing injured point • The Billikens became the first No. 9 seed to the program at his guard Tyus Edney in the starting lineup. win the Conference USA Tournament. alma mater on April Romar built a reputation as one of the nation’s top • Saint Louis upset a No. 1 team, Cincinnati, for 3, 2002. A point recruiters while an assistant at UCLA (1992-1996) the first time since the 1951-52 season when guard for the Hus- and was credited with recruiting much of the talent the Bills knocked off top-ranked Kentucky. kies’ 1978-79 and that formed the core of the Bruins’ title team. 1979-80 teams, • The Billikens won the first Bud Light Show- Romar is the 18th In three years at Saint Louis, Romar compiled a down by knocking off intrastate rival Missouri head coach in 51-44 (.537) record, including victories over nine for the first time since the 1970-71 season. Washington’s 101- different conference champions. His 51 wins rank After reaching the NCAA Tournament in his first year history. He is the first African-American No. 7 among all-time SLU coaches and is the season, expectations were high for Romar’s 2000- coach to lead the Washington basketball program. -

Arizona Basketball 2001-02

Wildcat Quick Facts Location . Tucson, Ariz. Arizona Basketball Founded . 1885 Enrollment . 35,400 President . Dr. Peter Likins 2001-02 Athletic Director . Jim Livengood Head Coach . Lute Olson ATHLETIC MEDIA RELATIONS Richard Paige Alma Mater . Augsburg ’58 McKale Center, Room 106 Men’s Basketball Contact Record/Years . 639-225 (.740)/28 P.O. Box 210096 Phone: (520) 621-4163 Record at UA . 447-133 (.771)/18 Tucson, AZ 85721-0096 FAX: (520) 621-2681 Assistant Coaches . Jim Rosborough Rodney Tention Jay John Game 1: Arizona (0-0) vs. No. 2 Maryland (0-0) Video/Recruiting Coord. Josh Pastner Date: Thursday, Nov. 8, 2001 Time: 9 p.m. EST Basketball Office . (520) 621-4813 Location: Madison Square Garden (19,763), New York, N.Y. Basketball SID . Richard Paige Radio: Wildcat Radio Network (Brian Jeffries/Ryan Hansen) TV: ESPN2 (Brad Nessler/Dick Vitale) e-mail . [email protected] Paige Home . (520) 790-4347 Arizona Probable Starters (2000-01 Stats) Office Phone . (520) 621-0916 No. Name Ht. Wt. Yr. Hometown PPG RPG APG FAX . (520) 621-2681 Press Row . (520) 621-4334 F 4 Luke Walton 6-8 241 Jr. San Diego, Calif. 5.5 3.9 3.2 Internet . www.arizonaathletics.com F 33 Rick Anderson 6-9 213 Jr. Long Beach, Calif. -- -- -- C 52 Isaiah Fox 6-9 265 Fr. Santa Monica, Calif. -- -- -- 2001-02 Schedule/Results G 22 Jason Gardner 5-10 181 Jr. Indianapolis, Ind. 10.9 3.0 4.1 Nov. 4 EA Sports All-Stars (Ex) 112-96 G 20 Salim Stoudamire 6-1 176 Fr. -

Combined Guide for Web.Pdf

2015-16 American Preseason Player of the Year Nic Moore, SMU 2015-16 Preseason Coaches Poll Preseason All-Conference First Team (First-place votes in parenthesis) Octavius Ellis, Sr., F, Cincinnati Daniel Hamilton, So., G/F, UConn 1. SMU (8) 98 *Markus Kennedy, R-Sr., F, SMU 2. UConn (2) 87 *Nic Moore, R-Sr., G, SMU 3. Cincinnati (1) 84 James Woodard, Sr., G, Tulsa 4. Tulsa 76 5. Memphis 59 Preseason All-Conference Second Team 6. Temple 54 7. Houston 48 Troy Caupain, Jr., G, Cincinnati Amida Brimah, Jr., C, UConn 8. East Carolina 31 Sterling Gibbs, GS, G, UConn 9. UCF 30 Shaq Goodwin, Sr., F, Memphis 10. USF 20 Shaquille Harrison, Sr., G, Tulsa 11. Tulane 11 [*] denotes unanimous selection Preseason Player of the Year: Nic Moore, SMU Preseason Rookie of the Year: Jalen Adams, UConn THE AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE Table Of Contents American Athletic Conference ...............................................2-3 Commissioner Mike Aresco ....................................................4-5 Conference Staff .......................................................................6-9 15 Park Row West • Providence, Rhode Island 02903 Conference Headquarters ........................................................10 Switchboard - 401.244-3278 • Communications - 401.453.0660 www.TheAmerican.org American Digital Network ........................................................11 Officiating ....................................................................................12 American Athletic Conference Staff American Athletic Conference Notebook