The Destination Image of Tana Toraja in the Perspective of German Projectors and Perceivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Walk on the Wild Side

SCAPES Island Trail your chauffeur; when asked to overtake, he regards you with bewildered incomprehension: “Overtake?” Balinese shiftlessness and cerebral inertia exasperate, particularly the anguished Japanese management with their brisk exactitude at newly-launched Hoshinoya. All that invigorates Bali is the ‘Chinese circus’. Certain resort lobbies, Ricky Utomo of the Bvlgari Resort chuckles, “are like a midnight sale” pulsating with Chinese tourists in voluble haberdashery, high-heeled, almost reeling into lotus ponds they hazard selfies on. The Bvlgari, whose imperious walls and august prices discourage the Chinese, say they had to terminate afternoon tea packages (another Balinese phenomenon) — can’t have Chinese tourists assail their precipiced parapets for selfies. The Chinese wed in Bali. Indians honeymoon there. That said, the isle inspires little romance. In the Viceroy’s gazebo, overlooking Ubud’s verdure, a honeymooning Indian girl, exuding from her décolleté, contuses her anatomy à la Bollywood starlet, but her husband keeps romancing his iPhone while a Chinese man bandies a soft toy to entertain his wife who shuts tight her eyes in disdain as Mum watches on in wonderment. When untoward circumstances remove us to remote and neglected West Bali National Park, where alone on the island you spot deer, two varieties, extraordinarily drinking salt water, we stumble upon Bali’s most enthralling hideaway and meet Bali’s savviest man, general manager Gusti at Plataran Menjangan (an eco-luxury resort in a destination unbothered about -

From the Jungles of Sumatra and the Beaches of Bali to the Surf Breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, Discover the Best of Indonesia

INDONESIAThe Insiders' Guide From the jungles of Sumatra and the beaches of Bali to the surf breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, discover the best of Indonesia. Welcome! Whether you’re searching for secluded surf breaks, mountainous terrain and rainforest hikes, or looking for a cultural surprise, you’ve come to the right place. Indonesia has more than 18,000 islands to discover, more than 250 religions (only six of which are recognised), thousands of adventure activities, as well as fantastic food. Skip the luxury, packaged tours and make your own way around Indonesia with our Insider’s tips. & Overview Contents MALAYSIA KALIMANTAN SULAWESI Kalimantan Sumatra & SUMATRA WEST PAPUA Jakarta Komodo JAVA Bali Lombok Flores EAST TIMOR West Papua West Contents Overview 2 West Papua 23 10 Unique Experiences A Nomad's Story 27 in Indonesia 3 Central Indonesia Where to Stay 5 Java and Central Indonesia 31 Getting Around 7 Java 32 & Java Indonesian Food 9 Bali 34 Cultural Etiquette 1 1 Nusa & Gili Islands 36 Sustainable Travel 13 Lombok 38 Safety and Scams 15 Sulawesi 40 Visa and Vaccinations 17 Flores and Komodo 42 Insurance Tips Sumatra and Kalimantan 18 Essential Insurance Tips 44 Sumatra 19 Our Contributors & Other Guides 47 Kalimantan 21 Need an Insurance Quote? 48 Cover image: Stocksy/Marko Milovanović Stocksy/Marko image: Cover 2 Take a jungle trek in 10 Unique Experiences Gunung Leuser National in Indonesia Park, Sumatra Go to page 20 iStock/rosieyoung27 iStock/South_agency & Overview Contents Kalimantan Sumatra & Hike to the top of Mt. -

The Meaning of Spaces in Toraja Traditional House Sisilia Mangopo1*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 436 1st Borobudur International Symposium on Humanities, Economics and Social Sciences (BIS-HESS 2019) The Meaning of Spaces in Toraja Traditional House Sisilia Mangopo1* 1 Departemen Ilmu Linguistik, Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper aims to explain the meaning of spaces in Toraja's traditional house known as Tongkonan. In every society, the spatial codes playing an important role to identify the structural meaning and functions of spaces. Tongkonan consists of three parts; they are the main house, the yard, and the barn. The part that discussed in this study is the yard called tarampak. The choice of tarampak as the source of research data because of its function as the center of ceremonies in Toraja community. The method that is used in this study uses descriptive qualitative. The data analyzed based on Danesi Perron's analysis of public spaces and sacred spaces. The result of the research shows that speech-utterances in rites are used to give function to space. Each part will be interpreted based on the type of ritual held and the speech that contained in the ritual. A type of space in Toraja society does not settle but can change based on the functions given. Keywords: Tongkonan, space, tarampak, ritual In addition to the shape of the building, one part of the 1. INTRODUCTION tongkonan that plays a major role in the life of the Toraja community is the yard called tarampak located in the Tana Toraja is one of a famous tourism destination located middle between banua toraya and alang. -

Hassles to Get a Glimpse of Torajan Culture

E N G I N E E R ' S E N G I N E E R ' S Adventures Hassles to Get a Glimpse of Torajan Culture Ir. Chin Mee Poon www.facebook.com/chinmeepoon Ir. Chin Mee Poon is a retired civil engineer who derives a great deal of joy and satisfaction from travelling to different parts of the globe, capturing fascinating insights of the places and people he encounters and sharing his experiences with others through his photographs and writing. Makassar by road, but there After spending two nights in is no direct public transport Mamasa, we left for Rantepao in between these two places. Tana Toraja in a car with a capacity We had to break the journey for 7 passengers. Scheduled to pick at Polewali, 246km from us up at the hotel at 7 a.m., the driver Makassar. Taking the advice showed up more than one hour late. of our hotel receptionist, There were already 4 other passengers we took a Grab car early in the car and the front seat that I one morning to go to Daya reserved through the hotel was taken Bus Terminal some 20km by a woman. The driver used the northeast of the city but direct way, going over the mountain there was not a single bus range between Mamasa and Tana there. After waiting for Toraja. Before this road was opened some time, we acceded a few years ago, we would have had to a man’s suggestion to to backtrack south to Parepare and go in a passenger car. -

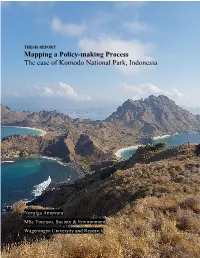

Mapping a Policy-Making Process the Case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia

THESIS REPORT Mapping a Policy-making Process The case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara MSc Tourism, Society & Environment Wageningen University and Research A Master’s thesis Mapping a policy-making process: the case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara 941117015020 Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: prof.dr. Edward H. Huijbens Examiner: dr. ir. Martijn Duineveld Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Science Cultural Geography Chair Group Master of Science in Tourism, Society and Environment i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tourism has been an inseparable aspect of my life, starting with having a passion for travelling until I decided to take a big step to study about it back when I was in vocational high school. I would say, learning tourism was one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life considering opportunities and experiences which I encountered on the process. I could recall that four years ago, I was saying to myself that finishing bachelor would be my last academic-related goal in my life. However, today, I know that I was wrong. With the fact that the world and the industry are progressing and I raise my self-awareness that I know nothing, here I am today taking my words back and as I am heading towards the final chapter from one of the most exciting journeys in my life – pursuing a master degree in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Never say never. In completing this thesis, I received countless assistances and helps from people that I would like to mention. Firstly, I would not be at this point in my life without the blessing and prayers from my parents, grandma, and family. -

Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Flores, Komodo (20 Días)

Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Flores, Komodo (20 días) Templo s, volcanes, culturas ancestral es y fauna endémica Indonesia, uno de los destinos más diversos, extensos y fascinantes del planeta, guarda secretos lejos del turismo de masas, lugares aún vírgenes, con fauna extraordinaria y grupos humanos con tradiciones ancestrales, como Sulawesi y Komodo . En cambio, Java y Bali, la s islas más visitadas del país, nos muestran sus impresionantes metrópolis con antiguos palacios y legado colonial, sus templos ancestrales únicos, sus volcanes activos y sus paisajes tropicials, sin olvidar sus playas. Ruta sugerida Itinerario sugerido: Día 1 .- Llegada a Yakarta i visita de la ciudad. Noche. Día 2.- Vuelo a Ujung Pandang (Sulawesi). Noche. Dia 3.- Visita de Makassar. Ruta al pais toraja pasando por los pueblos pesqueros. Noche en Rantepao. Día 4 .-. Visita de la zona de Tana Toraja con sus ritos ancestrales: Kete'kesu con las casas Tongkonan y la tumba gigante real, Lemo con las tumbas colgadas y las figuras Tau-Tau , la cueva funeraria de Londa , las piedras megal.lítiques de Bori y Lokomata , y la cima del monte Tinombayo , con vistas panorámicas de Rantepao. Día 5.- Retorno de 8 hrs con comida en Pare-Par e hasta Makassar y noche.. Día 6 .- Vuelo a Yogjakarta . Visitas: Kraton, Tama Sari, mercados, edificios coloniales ... Noche. Día 7.- Excursión a los templos de Borobudur y Mendut. Seguimos hacia los templos de Prambanan . Llegada en Solo y vista de l Kraton . Día 8.- Ruta hacia Mojokerto . De camino visita de la cascada Grojogan Sewu , monasterios del Gunung Lawu y lago de Sarangan . -

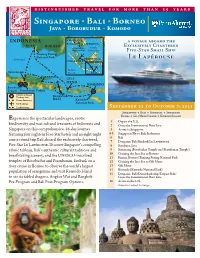

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI MOYO JAVA ISLAND KOMODO Borobudur Badas Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo SUMBAWA Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 23 to October 8, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Sumbawa u Semarang Kumai u Moyo Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, tropical E 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Denpasar, Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Ubud/Benoa/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Cruising the Java Sea to Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang, Java (Borobudur and Prambanan Temples) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Sumbawa river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Badas, Sumbawa/Moyo Island 14 Komodo Island (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons. -

Vernacular Architecture and Culture in the Nusantara: the Symbolic and Material Expressions of Home of the Tana Toraja, Minahasa, Dayak and the Balinese

R VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE AND CULTURE IN THE NUSANTARA: THE SYMBOLIC AND MATERIAL EXPRESSIONS OF HOME OF THE TANA TORAJA, MINAHASA, DAYAK AND THE BALINESE RISET KERJASAMA LUAR NEGERI UNIVERSITAS UDAYANA 2017 2. Aims of study • the Toraja, Minahasa and Dayak people in - how they take physical and symbolic form. • the relationship between social forms and spatial forms will take precedence, what are referred to as socio-spatial structures within the social science community. • The basic assumption here is that physical forms do not have a life of their own, uninformed by social process, and the aim here is to adopt this principle as a guiding vector in the study. 2. Aims of study • identification of social structure, belief systems and their relationship to architecture in the broadest sense of the term • An inductive study • a comparative study is necessary in order to highlight contrasts and similarities, and as far as is possible to reinforce both commonality and difference between an alien culture and one that is part of the life of this author and researcher 3. Research stage First year, taking a case study of Home of the Torajan People In Sulawesi Island-Indonesia 4. Research Products Journal Article Publication Suartika, GAM, Zerby, J, Cuthbert, AR (in press) ‘Doors of Perception to Space, Time-Meaning: Ideology, Religion, and Aesthetic in Balinese Development’ Space and Culture (SAC) Journal, Sage Publication International Seminar 2nd Geoplanning International Seminar 9-10 August 2017, Solo Surakarta Suartika, GAM (2017) ‘Global -

Publikasi Jurnal (8).Pdf

KERAGAMAN HAYATI DALAM RELIEF CANDI SEBAGAI BENTUK KONSERVASI LINGKUNGAN (Studi Kasus di Candi Penataran Kabupaten Blitar) Dra. Theresia Widiastuti, M.Sn. [email protected] Dr. Supana, M.Hum. [email protected] Drs. Djoko Panuwun, M.Sn. [email protected] Abstrak Tujuan jangka panjang penelitian ini adalah mengangkat eksistensi Candi Penataran, tidak saja sebagai situs religi, namun sebagai sumber pengetahuan kehidupan (alam, lingkungan, sosial, dan budaya). Tujuan khusus penelitian ini adalah melakukan dokumentasi dan inventarisasi berbagai bentuk keragaman hayati, baik flora maupun fauna, yang terdapat dalam relief Candi Penataran. Temuan dalam penelitian ini berupa informasi yang lengkap, cermat, dan sahih mengenai dokumentasi keragaman hayati dalam relief candi Penataran di Kabupaten Blitar Jawa Timur, klasifikasi keragaman hayati, dan ancangan tafsir yang dapat dugunakan bagi penelitian lain mengenai keragaman hayati, dan penelitian sosial, seni, budaya, pada umumnya. Kata Kunci: Candi, penataran, relief, ragam hias, hayati 1. Latar Belakang Masalah Citra budaya timur, khususnya budaya Jawa, telah dikenal di seluruh penjuru dunia sebagai budaya tinggi dan adi luhung. Hal ini sejalan dengan pendapat Sugiyarto (2011:250) yang menyatakan bahwa Jawa merupakan pusat peradaban karena masyarakat Jawa dikenal sebagai masyarakat yang mampu menyelaraskan diri dengan alam. Terbukti dengan banyaknya peninggalan-peninggalan warisan budaya dari leluhur Jawa, misalnya peninggalan benda-benda purbakala berupa candi. Peninggalan-peninggalan purbakala yang tersebar di wilayah Jawa memberikan gambaran yang nyata betapa kayanya warisan budaya Jawa yang harus digali dan dijaga keberadaannya. Candi Penataran, merupakan simbol axis mundy atau sumber pusat spiritual dan replika penataan pemerintahan kerajaan-kerajaan di Jawa Timur. Banyak penelitian yang telah dilakukan terhadap Candi Penataran, tetapi lebih menyoroti pada tafsir-tafsir historis istana sentris. -

Evangelism Program As the Main Strategy of Church Growth in Grace Bible Church of Mamasa, West Sulawesi

e-ISSN 2715-0798 https://ejournal.sttgalileaindonesia.ac.id/index.php/ginosko Volume 1, No 2, Mei 2020 (98-106) Evangelism Program as the Main Strategy of Church Growth in Grace Bible Church of Mamasa, West Sulawesi Agus Marulitua Marpaung Institut Agama Kristen Negeri Manado [email protected] Abstraksi: Evangelism is one of God’s programs to His People. Church as the gathering of God’s People should put attention for this matter. This research through qualitative research methodology describes how far the evangelism program may effect church growth in Grace Bible church of Mamasa. The church should consider Geographical, Social and cultural aspects of Mamasa regency in order to plan and making strategy of evangelism. Within ten years Grace Bible Church of Mamasa has growth as an established church where evangelism is the main strategy for Church Growing. Keywords: church; church growth; evangelism; Grace Bible Church INTRODUCTION Research Background Church is the gathering of people whom called from the darkness unto God’s Light. John Stott said that,” Church is believer, the gathering of people, who show the existence, solidarity, and their difference with another gathering only with one thing, God’s calling.1 Evangelism is one of God’s calling to the church.2 Proclaiming God’s love to the world that God has manifested His love through the life of Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ has died on the cross to pay the penalty of Sin, then He has risen from the dead to fulfill all God’s planning for the salvation of the World. -

The Genesis of Touristic Imagery in out of the Way Locales, Where Tourism Is Embryonic at Best, Has Yet to Be Examined

TOU54378 Adams 20/4/05 9:12 am Page 115 article ts The genesis of touristic tourist studies © 2004 sage publications imagery London, Thousand Oaks and Politics and poetics in the creation New Delhi vol 4(2) 115–135 1 DOI: 10.1177/ of a remote Indonesian island destination 1468797604054378 www.sagepublications.com Kathleen M. Adams Loyola University Chicago, USA abstract Although the construction and amplification of touristically-celebrated peoples’ Otherness on global mediascapes has been well documented, the genesis of touristic imagery in out of the way locales, where tourism is embryonic at best, has yet to be examined. This article explores the emergent construction of touristic imagery on the small, sporadically visited Eastern Indonesian island of Alor during the 1990s. In examining the ways in which competing images of Alorese people are sculpted by both insiders and outsiders, this article illustrates the politics and power dynamics embedded in the genesis of touristic imagery. Ultimately, I argue that even in remote locales where tourism is barely incipient, ideas and fantasies about tourism can color local politics, flavor discussions of identity and channel local actions. keywords Alor anthropologists and tourism Indonesia politics of tourism touristic imagery Numerous studies have chronicled the ways in which tourism projects have cre- ated exoticized, appealing, or sexualized images of ethnic Others (cf.Aitchison, 2001; Albers and James, 1983; Cohen, 1993, 1995, 1999; Dann, 1996; Deutschlander, 2003; Enloe, 1989; Selwyn, 1993, 1996). Such representations and images form the cornerstone of the cultural tourism industry.Disseminated via travel brochures, web pages, postcards, televised travel programs, and guide books,First these print and photographic imagesProof construct ‘mythic’ Others for touristic consumption (Selwyn, 1996). -

Singapore U Bali U Borneo Java U Borobudur U Komodo

distinguished travel for more than 35 years u u Singapore Bali Borneo Java u Borobudur u Komodo INDONESIA THAILAND a voyage aboard the Bangkok CAMBODIA Kumai BORNEO Exclusively Chartered Siem Reap South Angkor Wat China Sea Five-Star Small Ship Tanjung Puting National Park Java Sea INDONESIA Le Lapérouse SINGAPORE Indian Semarang Ocean BALI Surabaya GILI MENO JAVA KOMODO Borobudur Temple Prambanan Temple UNESCO World Heritage Site Denpasar Cruise Itinerary BALI Komodo Air Routing National Park Land Routing September 22 to October 7, 2021 Singapore u Bali u Surabaya u Semarang Kumai u Gili Meno Island u Komodo Island xperience the spectacular landscapes, exotic E 1 Depart the U.S. biodiversity and vast cultural treasures of Indonesia and 2 Cross the International Date Line Singapore on this comprehensive, 16-day journey 3 Arrive in Singapore featuring four nights in Five-Star hotels and an eight-night 4-5 Singapore/Fly to Bali, Indonesia 6 Bali cruise round trip Bali aboard the exclusively chartered, 7 Denpasar, Bali/Embark Le Lapérouse Five-Star Le Lapérouse. Discover Singapore’s compelling 8 Surabaya, Java ethnic tableau, Bali’s authentic cultural traditions and 9 Semarang (Borobudur Temple and Prambanan Temple) 10 Cruising the Java Sea to Borneo breathtaking scenery, and the UNESCO-inscribed 11 Kumai, Borneo/Tanjung Puting National Park temples of Borobudur and Prambanan. Embark on a 12 Cruising the Java Sea to Gili Meno river cruise in Borneo to observe the world’s largest 13 Gili Meno 14 Komodo (Komodo National Park) population of orangutans and visit Komodo Island 15 Denpasar, Bali/Disembark ship/Depart Bali/ to see its fabled dragons.