Volume XII-XIII (2013-2015) ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electric Light Orchestra – Secret

Electric Light Orchestra – Secret Messages [Double- Vinyl-Reissue] (34:06, 37:57; 2 LP,Sony Music/Legacy, 1983/2018) Immer wieder stolpert man als Musikliebhaber über skurrile Geschichten in Zusammenhang mit Veröffentlichungen berühmter Alben. Auch das im Juni 1983 erschienene Werk „Secret Messages“ vom „Electric Light Orchestra“ hat eine ungewöhnliche Entstehungsgeschichte. Jeff Lynne hatte im Vorfeld der Produktion eine besonders produktive Kompositionsphase, sodass während der Sessions zu „Secret Messages“ nicht weniger als 18 Songs aufgenommen wurden. Nichts lag näher als aus „Secret Messages“ ein Doppelalbum zu machen. Dass ELO in Sachen Doppelalben ein gutes Standing hatten, hatte bereits „Out Of The Blue“ eindrucksvoll bewiesen. Aber nix da – Der Boss von CBS legte wegen zu hoher Produktionskosten sein Veto ein, und so wurde aus „Secret Messages“ nur eine einfache LP/CD mit 10 bzw. 11 Stücken. Zwar wurden etliche gestrichene Stücke als Single-B- Seiten doch noch veröffentlicht, doch „Secret Messages“ war ein Kastrat und vielleicht auch deshalb deutlich weniger erfolgreich als sein Vorläufer. Dazu kam ein recht typischer Achtziger-PVC-Klang, der hie und da auch nicht dem Gusto der Fangemeinde entsprach. Zum Schutz Ihrer persönlichen Daten ist die Verbindung zu YouTube blockiert worden. Klicken Sie auf Video laden, um die Blockierung zu YouTube aufzuheben. Durch das Laden des Videos akzeptieren Sie die Datenschutzbestimmungen von YouTube. Mehr Informationen zum Datenschutz von YouTube finden Sie hier Google – Datenschutzerklärung & Nutzungsbedingungen. YouTube Videos zukünftig nicht mehr blockieren. Video laden 25 Jahre später erscheint das Album nun erstmals fast so wie ursprünglich geplant als Doppel-Album. „Fast“ deshalb, weil der Titel „Beatles Forever“ weiterhin ausgespart bleibt. -

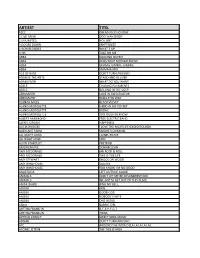

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Mr Blue Sky 2012 Mp3

Mr blue sky 2012 mp3 Continue Mr. Blue Sky: The Best of Electric Light Orchestra Compilation of Electric Light OrchestraPublication October 8, 2012 9 October 2012Gravation 2001-2012General RockDuration 48:51Disciographic FrontierProductor (s) Jeff LynneList Positions ViewNumber Eight in The United Kingdom Electric Light Orchestra Timeline Major Electric Light Orchestra (2011) Mr. Blue Sky: The Best of the Electric Light Orchestra (2012) Electric Light Orchestra Live (2013) Edit the Wikidata Data By Mr. Blue Sky The Very Best of Electric Light Orchestra (British Electric Light Orchestra, released in October 2012 frontier Records. Von Jeff Lynne, founder and member of the Electric Light Orchestra, told Rolling Stone magazine that the idea of recording Mr. Blue Sky arose when he listened to the band's original recordings and thought he could get a better result, given his long career as a music producer. Lynn decided to re-record a few songs from the band and started with Mr. Blue Sky. He told the magazine: I loved doing it, and when I heard them again and compared them to the old ones, I loved them even more. Her representative suggested that Lynn record more versions of songs from the Electric Light Orchestra, the first result of which were new recordings of both Evil Woman and Strange Magic. Given Lynn's personal satisfaction with the results, she continued to release an entire album of new recordings. The publication of Mr. Blue Sky: The Very Best of Electric Light Orchestra contains new recordings of the band's greatest hits in addition to two additional tracks: the new song Point of No Return and the live recording of Twilight recorded during the promotional tour. -

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Popo Laib -U F Iri 3I Nc 5

BILLBOARDS H E AT S E E K S R S ALBUM CHART COMPILED FROM A NATIONAL SAMPLE OF RETAIL STORE, MASS MERCHANT, SoundScan- The Heatseekers chart lists the best-selling titles by new and developing artists, defined as those who have never appeared in the Zo AND INTERNET SALES REPORTS COLLECTED, COMPILED, AND PROVIDED BY F- top 100 of The Billboard 200 chart. When an album reaches this level, the album and the artist's subsequent albums are immedi- ately ineligible to appear on the Heatseekers chart. All albums are available on cassette and CD. *Asterisk indicates vinyl LP is DECEMBER 9, 2000 w ¢ w 1 ARTIST TITLE available. Q Albums with the greatest sales gains. a 2000, Billboard /BPI Communications. I- 3 -i 5 3 U IMPRINT & NUMBER/DISTRIBUTING LABEL (SUGGESTED LIST PRICE OR EQUIVALENT FOR CASSETTE/CD) No. 1 Ms-- ® 35 87 SONICFLOOD GOTEE 2802 (15.98 CD) SONICFLOOD 1 1 14 SOULDECISION MCA 112361 (11.98/17.98) NO ONE DOES IT BETTER 21 20 28 NICKELBACK ROADRUNNER 8586 (8.98/13.98) THE STATE 2 2 4 LIFEHOUSE DREAMWORKS 450231 /INTERSCOPE (8.98/12.981 NO NAME FACE 28 RE -ENTRY RACHAEL LAMPA WORD 61068/EPIC (11.98 EQ/16.98) LIVE FOR YOU © 3 4 SAMANTHA MUMBA WILD CARD/POLYDOR 549413 /INTERSCOPE (11.98/17.98) GOTTA TELL YOU 29 16 8 PAUL OAKENFOLD LONDON -SIRE 31035 (19.98 CD) PERFECTO PRESENTS ANOTHER WORLD 4 69 BRAD PAISLEY ARISTA NASHVILLE 18871 /RLG (10.98/16.98) WHO NEEDS PICTURES 30 21 4 CHRIS RICE ROCKETOWWWORD 61474/EPIC (11.98 EQ/16.98) SMELL THE COLOR 9 ( 5 ) NEW LOUIE DEVITO E- LASTIK 5002 (16.98 CD) N.Y.C. -

ALBUMS CHART: P.20 APRIL 25,1981 0 N the Record of the Future

SINGLES CHART: P.9: ALBUMS CHART: P.20 APRIL 25,1981 The record of the future mugENwa a 1 n 0 EXHIBITORS' STANDS are filling up fast for the 3rd annual Dealer Tour, organised by Music & Video Week and scheduled to visit seven regional centres during THE COMPACT disc, lipped by its developing companies as the record of the September. Europe's leading music business paper 90p future, seen alongside a conventional LP and the Sony and Philips CD players. Judging by (he bookings coming in, it looks as if dealers Dealer asks attending the shows will be able to meet exhibitors when is RRP THE LASER BEAM from large and small record companies as well as the newly opened not RRP? video companies. A DISPUTE over whether telling Note the dates in your the public what they can "expect COMPACT DISC to pay" for a record is the same diary now: September 15, as re-imposing RRP has been Bristol Holiday Inn; aired by dealers who object to September 17, price stickers on two recent WEA Birmingham, Albany releases. The Saxon picture disc of And MAKES ITS BOW Hotel; September 21 The Bad Played On, and the Newcastle, Gosforth Park SALZBURG: The compact the compact disc's development, to be no more expensive than a Hotel; September 22 Echo and the Bunnymen describe these as "revolutionary conventional high-class record Crocodiles 12-inch four-track disc digital audio system was improvements" which, coupled with player. J. J. G. Ch. van Tilburg of Glasgow, Albany Hotel; single, were both stickered by introduced to the September 24 Leeds, WEA with the wording "expect "substantially better sound Philips expressed confidence that to pay around £1.05". -

May 2Nd Picks

RAP Memphis has always had a thriving underground CD YO GOTTI capable of producing major platinum superstars $17.98 such as Eightball & MJG, 3-6 Mafia and Project Pat. RATING BACK 2 BASICS TVT 2680 Next up to bat is Yo Gotti. 9 TOOL ROCK THEY HAVEN'T MISSED YET, THE CD ARE NOW RETURNING AFTER $18.98 RATING 10,000 DAYS RCA 81991 FIVE LONG YEARS. 7 CD DEM FRANCHISE BOYZ RAP CHOPPED & SCREWED $18.98 (SCREWED) ON TOP OF VERSION. RATING OUR GAME CAP 63690 6 THE ROCK GROUP WITH QUITE A CD PEARL JAM ROCK SUCCESSFUL HISTORY RETURNS FOR A NEW $18.98 STUDIO ALBUM FOR THE FIRST TIME IN RATING PEARL JAM RCA 71467 FOUR YEARS. 5 A MIX CD OF ALL THE HITS FROM CD VARIOUS ARTISTS RAP WRECKSHOP ARTISTS & MORE. THE $13.98 REGULAR AND THE SCREWED VERSION ARE RATING DA HEAVYWEIGHTERS WKS 8762 IN ONE PACKAGE. 5 RAP THE FRONTMAN OF 2 LIVE CREW RETURNS WITH CD UNCLE LUKE GUESTS INCLUDING PETEY PABLO, PITBULL, TRICK $9.98 MY LIFE AND FREAKY DADDY & MORE. FIRST 2 SINGLES ARE POP THAT RATING P*SSY REMIX & HOLLA AT CHA HOMEBOY. TIMES UBO 11120 4 GREEN, AL R&B THIS EXPANDED EDITION CD INCLUDES THREE UNRELEASED $17.98 RATING BELLE (EXPANDED) CAP 73611 TRACKS. 2 SEE THIS POPULAR DJ HANG OUT WITH CD DJ DEMP DVD TRICK DADDY, PITBULL, LIL' FLIP, $14.98 YOUNGBLOODZ, MIKE JONES, COO COO CAL RATING DIRTY FOR LIFE MRC 30013 & PRETTY RICKY. 1 28 HITS AND 1 UNRELEASED TRACK. HITS CD COLE, NAT KING R&B INCLUDE UNFORGETTABLE, MONA LISA, $18.98 SMILE, LET'S FACE THE MUSIC. -

Kirkland Performance Center Brings Local and World Renowned Artists to Kirkland in 2016 Upcoming Winter Show Details

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 22, 2016 CONTACT: Skye Stoury, Marketing & Communications Manager [email protected]; (425) 828-0422 x 224 General Info: http://www.kpcenter.org/ Tickets/Show Info: (425) 893-9900; http://www.kpcenter.org/content/2015-2016-season-at-a-glance Kirkland Performance Center Brings Local and World Renowned Artists to Kirkland in 2016 Upcoming Winter Show Details Ladysmith Black Mambazo South African / World 1/28, 1/29, 8:00pm Andy McKee Acoustic Guitar 2/6, 8:00pm Prom Queen Local / Indie / Pop / Rock 2/13, 8:000pm Indigo Girls (Sold Out) Folk 2/27, 8:00pm Twisted Flicks Improv Comedy / Film 3/4, 8:00pm Lucy Woodward Jazz /R&B / Pop 3/5, 8:00pm Imagination Theater Live Radio Drama 3/14, 7:30pm SRO: ELO Rockaria! Rock 3/19, 8:00pm Cirque Alfonse: Timber! Cirque / Dance 4/22, 4/23, 4/24, many times KIRKLAND, Wash. – Kirkland Performance Center (KPC) is pleased to present both local favorites and Grammy Award winners in 2016. With a variety of music genres, cirque shows, and live improv comedy, there is truly something for everyone at KPC this winter and into the spring. Individual tickets are on sale now. The first half of KPC’s season included eight sold out performances, a record for the theater. Indigo Girls, a late addition to KPC’s 2015-2016 season sold out within seven days of the show being announced to the public. For patrons who were not able to get tickets to see Indigo Girls, there are many other exciting performers coming to KPC in the remainder of their season. -

Record-World-1980-01

111.111110. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS KOOL & THE GANG, "TOO HOT" (prod. by THE JAM, "THE ETON RIFLES" (prod. UTOPIA, "ADVENTURES IN UTO- Deodato) (writers: Brown -group) by Coppersmith -Heaven) (writer:PIA." Todd Rundgren's multi -media (Delightful/Gang, BMI) (3:48). Weller) (Front Wheel, BMI) (3:58). visions get the supreme workout on While thetitlecut fromtheir This brash British trio has alreadythis new album, originally written as "Ladies Night" LP hits top 5, topped the charts in their home-a video soundtrack. The four -man this second release from that 0land and they aim for the same unit combineselectronicexperi- album offers a midtempo pace success here with this tumultu- mentation with absolutely commer- with delightful keyboards & ousrocker fromthe"Setting cialrocksensibilities.Bearsville vocals. De-Lite 802 (Mercury). Sons" LP. Polydor 2051. BRK 6991 (WB) (7.98). CHUCK MANGIONE, "GIVE IT ALL YOU MIKE PINERA, "GOODNIGHT MY LOVE" THE BABYS, "UNION JACK." The GOT" (prod. by Mangione) (writ- (prod. by Pinera) (writer: Pinera) group has changed personnel over er: Mangione) (Gates, BMI) (3:55). (Bayard, BMI) (3:40). Pinera took the years but retained a dramatic From his upcoming "Fun And the Blues Image to #4 in'70 and thundering rock sound through- Games" LP is this melodic piece withhis "Ride Captain,Ride." out. Keyed by the single "Back On that will be used by ABC Sports He's hitbound again as a solo My Feet Again" this new album in the 1980 Winter Olympics. A actwiththistouchingballad should find fast AOR attention. John typically flawless Mangione work- that's as simple as it is effective. -

October 18, 1979

OCTO ' BE~ 18, 1979 ISSUE 353 '- _. UNIVERSITY Of MISSOURI/SAINT LOUIS - Homecoming not ready for burial "The only thing we are not Rick.Jackoway going to have is a dinner," Blanton explained. Also the tra In a grave message to UMSL ditional soccer game will not be students, a tombstone was e involved in this year's festivities. rected last week near the out This year, Blanton said, the . door basketball court. homecoming will be part of a Etched on the tombstone are spirit week from Nov. 26 to 3~. the words " R.LP./UMSLlHC/ There will be some sort of social 1979/ Do you care?" Much spec· function where the king and ulation centered over who or Queen of homecoming will be what is He. But for some people announced, he said. But the the meaning was quite clear. traditional dinner/ dance will not For the past few months there be included because of lack of has been much concern about funds. the future of homecoming at The Student Budget Commit UMSL. The tombstone caused tee, Blanton explained, cut out more vocal discussion of home dinner subsidies for all organiza coming. tions. But, to abuse an old line, the Blanton said the Second An . reports of homecomings death nual Boat Race, an intercollegate .. PAYING HOMAGE: Curious students view a grave marldng the rumored death of UMSL Homecoming are ·greatly exagerated, accord tug-of-war, and other activities activities. Despite the monument's ImpUcations, such activities will be held this year [photo by WOey ing to Rick Blanton, director ' of will be included during Spirit PrIce]. -

Tim Young, Adam Fine, Tricia Southard.Pdf

\ earn name here TRASHMASTERS 2004 - UT-CHATTANOOGA ) Tim Young, Adam Fine, and Tricia Southard , J t-/ILJjl£; // / He led the American League in hits in his rookie season of 1942, but then spent three years fighting in World War / /fI. While with Detroit in 1952, he helped Virgil Trucks record his second no-hitter of the season after admitting that he ,/' misplayed a Phil Rizzuto ball originally called a hit. The goat of the 1946 World Series when he allowed Enos Slaughter / to score, FrP name this Red Sox shortstop, born John Paveskovich, the namesake of the right field foul pole in Fenway Park. Answer: Johnny Pesky 2. The title came about as a catch phrase among band members about what they hoped would happen to people "behaving in a shitty way." The piano riff in the chorus echoes another song about someone acting badly, the Beatles' "Sexy Sadie." The lyrics decry a man who "buzzes like a detuned radio" and a girl with a "Hitler hairdo," and hope that the titular entity will arrest them. We are told in the coda that the narrator "For a minute there . .I lost myself' over and over. FTPname this 1997 song, the third single from "OK Computer," a major hit for Radiohead. Answer: Karma Police 3. A 1979 graduate of Davidson College, this woman won an investigative reporting honor from the North Carolina Press Association for a series of articles about crime and prostitution in Charlotte. Her first book, An Uncommon Friend, was a biography of Billy Graham's wife, but her six years of work for the Virginia Chief Medical Examiner's Office inspired her best know series of a dozen novels. -

Presents a Student Composers Recital

presents a Student Composers Recital Program Suite for Percussion Trio ............................................................................................... Adam Schweyer (b. 2001) I. Ostinato II. Unison III. Call & Response IV. Accompanied Melody V. Canon VI. Free Form Adam Schweyer, bongos Caleb Pieper, tom-toms Peter Stigdon, bass drum Omnes una manet nox ............................................................................................ Benjamin Verswijver (b. 2001) Act I: The King’s Castle Act II: The King’s Conquest Act III: The People’s Lament Andrew Kuhnau and Caleb Pieper, trumpets Karolina Zawitkowska, horn Andrew Schroeder, trombone AJ Howard, tuba Sunday, February 28, 2021 Chapel of Our Lord 7:00 p.m. since feeling is first ................................................................................................................ Anaka Riani (b. 1999) Miranda Flanagan, soprano Ulysses Espino, guitar since feeling is first who pays any attention to the syntax of things will never wholly kiss you; wholly to be a fool while Spring is in the world my blood approves, and kisses are a better fate than wisdom lady i swear by all flowers. Don’t cry – the best gesture of my brain is less than your eyelids’ flutter which says we are for each other; then laugh, leaning back in my arms for life’s not a paragraph And death i think is no parenthesis - e e cummings Isaiah 51:11................................................................................................................... Samantha English (b. 1999)