Ice Age National Scenic Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2021 PRESIDENT’S Report

R Falls BARRON LANGLADE Medford W Antigo Merrill i s ST. CROIX TAYLOR c Marinette DUNN CHIPPEWA o n Chippewa s MENOMINEE Wausau i n DOOR Falls OCONTO Menomonie MARATHON Sturgeon R River R Bay Eau Claire i Falls v CLARK e SHAWANO PIERCE r EAU CLAIRE G R E E N B A Y PEPIN Marshfield Green Algoma Stevens Bay Point SPRING 2021 PRESIDENT’S report to spring, a season for enjoying nature and the glorious opportunity to be outside. Whether you walk your dog, head out with your family for a day hike, or have taken on the challenge to become a Thousand-Miler, the Ice Age National Scenic Trail provides a chance for quiet recreation while following the glacial history of Wisconsin. During the past year, a record number of people discovered the Ice Age Trail, and the Alliance membership has grown to over 4,500 strong. I’m excited to welcome all our new members. 2020 was an excellent year for land acquisition, thanks to the many who contributed to our land protection efforts. It was also the year where despite COVID-19 limitations, 1,499 volunteers donated 53,297 hours as dedicated caretakers of our wonderful Trail. While some of our efforts understandably shifted during the pandemic, we continued to maintain our high standards of providing a top-notch Trail experience for all. In 2021, I invite you to join one of the small-scale Trailbuilding and Stewardship Reconnect projects available through your chapter or one of the large-scale events scheduled later this summer. -

Official List of Wisconsin's State Historic Markers

Official List of Wisconsin’s State Historical Markers Last Revised June, 2019 The Wisconsin State Historical Markers program is administered by Local History-Field Services section of the Office of Programs and Outreach. If you find a marker that has been moved, is missing or damaged, contact Janet Seymour at [email protected] Please provide the title of the marker and its current location. Each listing below includes the official marker number, the marker’s official name and location, and a map index code that corresponds to Wisconsin’s Official State Highway Map. You may download or request this year’s Official State Highway Map from the Travel W isconsin website. Markers are generally listed chronologically by the date erected. The marker numbers below jump in order, since in some cases markers have been removed for a variety of reason. For instance over time the wording of some markers has become outdated, in others historic properties being described have been moved or demolished. Number Name and Location Map Index 1. Peshtigo Fire Cemetery ................................................................................................................................5-I Peshtigo Cemetery, Oconto Ave, Peshtigo, Marinette County 2. Jefferson Prairie Settlement ........................................................................................................................11-G WI-140, 4 miles south of Clinton, Rock County 5. Shake Rag.................................................................................................................................................................10-E -

Trail Challenge Resources

Trail Challenge Resources Hiking Trails Ice Age National Scenic Trail ● Description: One of only 11 National Scenic Trails in the country, the Ice Age Trail is a 1,000-mile footpath contained entirely within the state of Wisconsin. Ancient glaciers carved the path through rocky terrain, open prairies, and peaceful forests. Now, day hikers, backpackers, and outdoor lovers of all ages rely on the Ice Age Trail for a place to unplug, relax, and enjoy nature. ● Ice Age Trail Map Interstate State Park, MN ● Description: Interstate State Park includes 293 acres of diverse plant and wildlife habitat. Established in 1895, it protects a unique landscape and globally-significant geology along the St. Croix River. A billion years ago, dark basalt rock formed here when lava escaped from a crack in the earth’s crust. Just ten thousand years ago, water from melting glaciers carved the river valley. Within that water were fast moving whirlpools of swirling sand and water that wore deep holes into the rock. Today, we call these holes glacial potholes and you can see more than 400 examples of them at the park. ● Interstate State Park Map Interstate State Park, WI ● Description: There are more than nine miles of hiking trails in the park that offer the walker many opportunities for viewing the spectacular scenery and natural attributes of the park. Guided hikes are offered during the summer months. Pets must be on a leash 8 feet or shorter at all times. Hiking trails vary in difficulty. Not all trails are surfaced; use caution on steep bluffs and near cliffs. -

Ice Age National Scenic Trail Corridor Plan and Environmental Assessment for Kewaunee, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin

ICE AGE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL CORRIDOR PLAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR KEWAUNEE, MANITOWOC, AND SHEBOYGAN COUNTIES, WISCONSIN Prepared by: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Parks and Recreation National Park Service, Ice Age National Scenic Trail Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission December, 2006 PUB-PR-811 06 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Board Gerald M. O'Brien, Chair Christine L. Thomas, Vice Chair Jonathan P. Ela, Secretary David Clausen Howard D. Poulson John W. Welter Stephen D. Willett Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Box 7921 Madison, WI 53707-7921 This publication is available in alternative format (large print, Braille, audio tape, etc.) upon request. Please call 608-266-2181 for more information. You can also view this document on the Web at: http://www.dnr.wi.gov/master_planning/ PUB-PR-811 06 Acknowledgments Lake Michigan Corridor Ice Age Trail Planning Team Lake Michigan Corridor Ice Age Trail Core Planning Team Jean Potter Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation Jeffrey Prey WDNR - Bureau of Parks and Recreation Mark Walter Bay Lake Regional Planning Commission Pam Schuler National Park Service Mary Tano National Park Service Lake Michigan Corridor Ice Age Trail Guidance / Oversight Team Peter Biermeier WDNR - Bureau of Parks and Recreation Tom Gilbert National Park Service Andrew Hanson Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation Mapping and GIS Services Tony Bellovary Bay Lake Regional Planning Commission Ice Age National Scenic Trail Corridor Plan and Environmental Assessment For Kewaunee, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin December, 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary – Ice Age National Scenic Trail Corridor Plan For Kewaunee, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan Counties, Wisconsin............................................................................................. -

Hoofer Mountaineering Club 800 Langdon St., Madison, WI 53706

Hoofer Mountaineering Club 800 Langdon St., Madison, WI 53706 To: the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board, and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Re: implementation of Act 168, The Sporting Heritage Act For the sake of public safety, we recommend that the Department of Natural Resources and the Natural Resources Board close to hunting and trapping those non-designated use areas in State Parks that are regularly used for rock climbing, ice climbing, and bouldering. Our specific recommendations are detailed below. Climbing in State Parks Rock climbing is a traditional outdoor recreation with nearly a century-long history in Wisconsin, and is recognized as such in NR 1.33. Rock climbing, like hunting, is allowed solely in non-designated use areas. Some DNR personnel are aware that climbing goes on at some State Parks, but none have a thorough understanding of when and where rock climbing occurs. NR 1.33 stipulates that rock climbing be considered in planning, but for decades this has been at best inconsistent. The previous hunting maps and the currently proposed hunting and trapping maps for State Parks demonstrate this lack of knowledge and lack of consideration. Our recommendations are intended to fill that gap. Hunting and Climbing What hunters gain from Act 168 are simplified regulations. No more special permits for State Parks. If hunting is in season anywhere, it is in season in State Parks, and with any weapon for any game. Trapping will essentially be another form of hunting. Both the NRB and the DNR have stated that implementation of Act 168 should give hunters the maximum opportunity to hunt, without displacing other park users. -

Wisconsin's John Muir

Wisconsin’s John Muir An Exhibit Celebrating the Centennial of the National Park Service “Oh, that glorious Wisconsin wilderness! “Everything new and pure in the very prime of the spring when Nature’s pulses were beating highest and mysteriously keeping time with our own!” “Wilderness is a necessity... Mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.” This exhibit was made possible through generous support from the estate of John Peters and the Follett Charitable Trust Muir in Wisconsin “When we first saw Fountain Lake Meadow, on a sultry evening, sprinkled with millions of lightning- bugs throbbing with light, the effect was so strange and beautiful that it seemed far too marvelous to be real.” John Muir (1838–1914) was one of America’s most important environmental thinkers and activists. He came to Wisconsin as a boy, grew up near Portage, and attended the University of Wisconsin. After decades of wandering in the mountains of California, he led the movement for national parks and helped create the Sierra Club. But for much of his life, Muir’s call to protect wild places fell on deaf ears. Muir studied science in Madison but quit in 1863 without a degree, “...leaving one University for another, the Wisconsin University for the University of the Wilderness.” Muir’s letter to the classmate who taught him botany at UW The Movement for National Parks Yosemite Valley “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike.” In 1872, Congress named Yellowstone the first national park. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Wisconsin's Wetland Gems

100 WISCONSIN WETLAND GEMS ® Southeast Coastal Region NE-10 Peshtigo River Delta o r SC-1 Chiwaukee Prairie NE-11 Point Beach & Dunes e i SC-2 Des Plaines River NE-12 Rushes Lake MINNESOTA k e r a p Floodplain & Marshes NE-13 Shivering Sands & L u SC-3 Germantown Swamp Connected Wetlands S SC-4 Renak-Polak Woods NE-14 West Shore Green Bay SU-6 SU-9 SC-5 Root River Riverine Forest Wetlands SU-8 SU-11 SC-6 Warnimont Bluff Fens NE-15 Wolf River Bottoms SU-1 SU-12 SU-3 SU-7 Southeast Region North Central Region SU-10 SE-1 Beulah Bog NC-1 Atkins Lake & Hiles Swamp SU-5 NW-4 SU-4 SE-2 Cedarburg Bog NC-2 Bear Lake Sedge Meadow NW-2 NW-8 MICHIGAN SE-3 Cherokee Marsh NC-3 Bogus Swamp NW-1 NW-5 SU-2 SE-4 Horicon Marsh NC-4 Flambeau River State Forest NW-7 SE-5 Huiras Lake NC-11 NC-12 NC-5 Grandma Lake NC-9 SE-6 Lulu Lake NC-6 Hunting River Alders NW-10 NC-13 SE-7 Milwaukee River NC-7 Jump-Mondeaux NC-8 Floodplain Forest River Floodplain NW-6 NC-10 SE-8 Nichols Creek NC-8 Kissick Alkaline Bog NW-3 NC-5 NW-9 SE-9 Rush Lake NC-9 Rice Creek NC-4 NC-1 SE-10 Scuppernong River Area NC-10 Savage-Robago Lakes NC-2 NE-7 SE-11 Spruce Lake Bog NC-11 Spider Lake SE-12 Sugar River NC-12 Toy Lake Swamp NC-6 NC-7 Floodplain Forest NC-13 Turtle-Flambeau- NC-3 NE-6 SE-13 Waubesa Wetlands Manitowish Peatlands W-7 NE-9 WISCONSIN’S WETLAND GEMS SE-14 White River Marsh NE-2 Northwest Region NE-8 Central Region NE-10 NE-4 NW-1 Belden Swamp W-5 NE-12 WH-5 Mink River Estuary—Clint Farlinger C-1 Bass Lake Fen & Lunch NW-2 Black Lake Bog NE-13 NE-14 ® Creek Sedge Meadow NW-3 Blomberg Lake C-4 WHAT ARE WETLAND GEMS ? C-2 Bear Bluff Bog NW-4 Blueberry Swamp WH-2WH-7 C-6 NE-15 NE-1 Wetland Gems® are high quality habitats that represent the wetland riches—marshes, swamps, bogs, fens and more— C-3 Black River NW-5 Brule Glacial Spillway W-1 WH-2 that historically made up nearly a quarter of Wisconsin’s landscape. -

Appendix N Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forests

Final Environmental Impact Statement Appendix N Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forests Existing and Proposed RNAs, SMAs, and OG Final Environmental Impact Statement Appendix N Existing and Proposed RNAs, SMAs, and Old Growth & Natural Features Complexes (MA 8 E, F, and G) RNA = Research Natural Area SMA = Special Management Area OG = Old Growth & Natural Features Complex * = prior designation Ecological Reference Areas Chequamegon Table N-1. Chequamegon Ecological Reference Areas Proposed /Existing Site ID# Name District Designation LTA Ka04 (A) A501 Moquah Natural Area Washburn RNA* LTA Ka07 (B) B501 Barksdale Ponds (Bladder Lake) Washburn SMA B502 Wanoka Lake Esker Washburn OG LTA Ja03 C C501 Long Lake Branch Washburn OG C502 Upper Fourmile Creek Washburn OG LTA Jc05 (D) D201 Dry Lake Great Divide RNA D202 Iron Creek Great Divide OG D203 Hell Hole Creek Great Divide OG D204 Minnow Creek Great Divide OG D401 Bullhead Lake Great Divide OG D402 Eighteen Mile Creek Great Divide SMA D501 Lake Owen Washburn SMA N-1 Appendix N Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forests Proposed /Existing Site ID# Name District Designation D503 Drummund Woods Washburn SMA D504 Perch & Lund Lakes Washburn OG LTA Jc06 (E) E401 Southwest Lake Great Divide OG E501 Camp Nine Pines Washburn RNA & SMA E502 Pigeon Lake Washburn OG E503 Bearsdale Creek & Hyatt Spring Washburn RNA & SMA E504 Northeast Lake Washburn SMA E505 Mountain Lake Washburn OG E506 Lake Sixteen Washburn OG LTA Jc13 (F) F501 Big Brook Washburn OG F502 Tars Creek Washburn OG LTA Jc07 (G) G401 Rock Lake Great Divide SMA G402 Namekagon Fen Great Divide RNA G403 203 Hemlock Swamp Great Divide OG G404 Burke Tract Great Divide RNA & SMA LTA Jb01 (H) H201 St. -

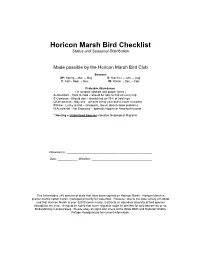

Horicon Marsh Bird Checklist Status and Seasonal Distribution

Horicon Marsh Bird Checklist Status and Seasonal Distribution Made possible by the Horicon Marsh Bird Club Seasons SP: Spring – Mar. – May S: Summer – June – Aug. F: Fall – Sept. – Nov. W: Winter – Dec. – Feb. Probable Abundance ( in suitable habitats and proper times ) A Abundant - Hard to miss – should be able to find on every trip C Common - Should see – should find on 75% of field trips U Uncommon - May see – present every year but in lesser numbers R Rare - Lucky to find – infrequent, few or identification problems H Accidental - Not Expected – sporadic reports or historical records * Nesting – Underlined Species indicates Neotropical Migrants Observer(s): ____________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Weather: _____________________________________ This list includes 288 species of birds that have been sighted on Horicon Marsh. Horicon Marsh is predominantly cattail marsh, managed primarily for waterfowl. However, due to the wide variety of habitat and that Horicon Marsh is over 32000 acres in size, it attracts an abundant diversity of bird species throughout the year. It should be noted that some migrants might be present for only two weeks or so. Birdwatching is encouraged. Please obey all signs and check at the State DNR and National Wildlife Refuge Headquarters for current information. Sp S F W Loons __ Common Loon R R H Grebes __ Pied-billed Grebe* CCCR __ Horned Grebe R R __ Red-necked Grebe* R R R __ Eared Grebe R R R Pelicans __ American White Pelican* C C C Cormorants __ Double-crested Cormorant* C C C R Bitterns, Herons __ American Bittern* UUUR __ Least Bittern* U U U __ Great Blue Heron* AAAR __ Great Egret* C C C __ Snowy Egret R R R __ Little Blue Heron R R R __ Cattle Egret R R R __ Green Heron* U U U __ Black-crowned Night-Heron* CCCR American Vultures __ Turkey Vulture* U U R Swans, Geese and Ducks __ Gr. -

2009 STATE PARKS GUIDE.Qxd

VISITOR INFORMATION GUIDE FOR STATE PARKS, FORESTS, RECREATION AREAS & TRAILS Welcome to the Wisconsin State Park System! As Governor, I am proud to welcome you to enjoy one of Wisconsin’s most cherished resources – our state parks. Wisconsin is blessed with a wealth of great natural beauty. It is a legacy we hold dear, and a call for stewardship we take very seriously. WelcomeWelcome In caring for this land, we follow in the footsteps of some of nation’s greatest environmentalists; leaders like Aldo Leopold and Gaylord Nelson – original thinkers with a unique connection to this very special place. For more than a century, the Wisconsin State Park System has preserved our state’s natural treasures. We have balanced public access with resource conservation and created a state park system that today stands as one of the finest in the nation. We’re proud of our state parks and trails, and the many possibilities they offer families who want to camp, hike, swim or simply relax in Wisconsin’s great outdoors. Each year more than 14 million people visit one of our state park properties. With 99 locations statewide, fun and inspiration are always close at hand. I invite you to enjoy our great parks – and join us in caring for the land. Sincerely, Jim Doyle Governor Front cover photo: Devil’s Lake State Park, by RJ & Linda Miller. Inside spread photo: Governor Dodge State Park, by RJ & Linda Miller. 3 Fees, Reservations & General Information Campers on first-come, first-served sites must Interpretive Programs Admission Stickers occupy the site the first night and any Many Wisconsin state parks have nature centers A vehicle admission sticker is required on consecutive nights for which they have with exhibits on the natural and cultural history all motor vehicles stopping in state park registered. -

Wisconsin's Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015)

Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Prepared by: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources with Assistance from Conservation Partners, June 30th, 2008 06/19/2008 page 2 of 93 Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Acknowledgments Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan is a roadmap of conservation actions needed to ensure our wildlife and natural communities will be with us in the future. The original plan provides an immense volume of data useful to help guide conservation decisions. All of the individuals acknowledged for their work compiling the plan have a continuous appreciation from the state of Wisconsin for their commitment to SGCN. Implementing the conservation actions is a priority for the state of Wisconsin. To put forward a strategy for implementation, there was a need to develop a process for priority decision-making, narrowing the list of actions to a more manageable number, and identifying opportunity areas to best apply conservation actions. A subset of the Department’s ecologists and conservation scientists were assigned the task of developing the implementation strategy. Their dedicated commitment and tireless efforts for wildlife species and natural community conservation led this document. Principle Process Coordinators Tara Bergeson – Wildlife Action Plan Implementation Coordinator Dawn Hinebaugh – Data Coordinator Terrell Hyde – Assistant Zoologist (Prioritization