Chapter 33 Groundwater Recharge Chapter 33 Groundwater Recharge Part 631 National Engineering Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater Recharge from a Changing Landscape

ST. ANTHONY FALLS LABORATORY Engineering, Environmental and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Project Report No. 490 Groundwater Recharge from a Changing Landscape by Timothy Erickson and Heinz G. Stefan Prepared for Minnesota Pollution Control Agency St. Paul, Minnesota May, 2007 Minneapolis, Minnesota The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, religion, color, sex, national origin, handicap, age or veteran status. 2 Abstract Urban development of rural and natural areas is an important issue and concern for many water resource management organizations and wildlife organizations. Change in groundwater recharge is one of the many effects of urbanization. Groundwater supplies to streams are necessary to sustain cold water organisms such as trout. An investigation of the changes of groundwater recharge associated with urbanization of rural and natural areas was conducted. The Vermillion River watershed, which is both a world class trout stream and on the fringes of the metro area of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, was used for a case study. Substantial changes in groundwater recharge could destroy the cold water habitat of trout. In this report we give first an overview of different methods available to estimate recharge. We then present in some detail two models to quantify the changes in recharge that can be expected in a developing area. We finally apply these two models to a tributary watershed of the Vermillion River. In this report we discuss several techniques that can be used to estimate groundwater recharge: (1) the recession-curve-displacement method and (2) the base-flow-separation method that both use only streamflow records (Rutledge 1993, Lee and Chen 2003); (3) a recharge map developed by the USGS for the state of Minnesota (Lorenz and Delin 2007); (4) a minimal recharge map developed by the Minnesota Geological Survey using statistical methods (Ruhl et al. -

Root Zone Salinity Modeling Within Kalaat El Andalous Irrigated District (Tunisia) Using Saltmod Model

Root zone salinity modeling within Kalaat El Andalous irrigated district (Tunisia) using SaltMod model Ahmed Saidi 1*, Moncef Hammami 2, Hedi Daghari 3, Hedi Ben Ali4, Amor Boughdiri 5 1,3 Carthage University, National Agronomic Institute of Tunis, 43 Charles Nicolle Street, Mahrajene City, 1082 Tunis, Tunisia 2,5 Carthage University, Higher Agronomic School of Mateur, Road of Tabarka, 7030 Mateur, Tunisia 4Agency of agricultural investment promotion, 6000 Gabes, Tunisia Abstract—SaltMod simulations indicate a slight change of root zone salinity remaining between 3 and 6 dS/m and do not causes risks to forage and cereal crops. However, such salinity is causing a yield decrease of 10 to 20% for tomato crop. During the next 10 years, groundwater water table depth will range between 1.33 and 1.76 m. and remains lower than that of the root zone (0.6 m). Therefore, groundwater table will not pose problems as long as we keep the same management conditions during this period. Moreover, the simulation of drainage system depth variation impacts on root zone salinity indicates that a decrease of drainage lines depth does not affect root zone salinity which remains constant (4.94 dS/m and 3.68 dS/m respectively during the first season and the second season). Regarding groundwater table depth, it is noted that there is a variation for each drainage lines depth variation and groundwater level is ranging from 1.26 to 0.26 m and 1.76 to 0.76 m during the first season and the second season respectively. Thus, optimum drainage lines depth corresponds to that for which salinity and groundwater level have acceptable values not threatening crops and generating minimum drainage flow. -

Recommended Standards for Wastewater Facilities

RECOMMENDED STANDARDS for WASTEWATER FACILITIES POLICIES FOR THE DESIGN, REVIEW, AND APPROVAL OF PLANS AND SPECIFICATIONS FOR WASTEWATER COLLECTION AND TREATMENT FACILITIES 2014 EDITION A REPORT OF THE WASTEWATER COMMITTEE OF THE GREAT LAKES - UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER BOARD OF STATE AND PROVINCIAL PUBLIC HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGERS MEMBER STATES AND PROVINCE ILLINOIS NEW YORK INDIANA OHIO IOWA ONTARIO MICHIGAN PENNSYLVANIA MINNESOTA WISCONSIN MISSOURI PUBLISHED BY: Health Research, Inc., Health Education Services Division P.O. Box 7126 Albany, N.Y. 12224 Phone: (518) 439-7286 Visit Our Web Site http://www.healthresearch.org/store/ten-state-standards Copyright © 2014 by the Great Lakes - Upper Mississippi River Board of State and Provincial Public Health and Environmental Managers This document, or portions thereof, may be reproduced without permission if credit is given to the Board and to this publication as a source. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................... v 10 ENGINEERING REPORTS AND FACILITY PLANS 10. General ............................................................................................................................. 10-1 11. Engineering Report Or Facility Plan ................................................................................ 10-1 12. Pre-Design Meeting ....................................................................................................... 10-12 -

The Federal Role in Groundwater Supply

The Federal Role in Groundwater Supply Updated May 22, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45259 The Federal Role in Groundwater Supply Summary Groundwater, the water in aquifers accessible by wells, is a critical component of the U.S. water supply. It is important for both domestic and agricultural water needs, among other uses. Nearly half of the nation’s population uses groundwater to meet daily needs; in 2015, about 149 million people (46% of the nation’s population) relied on groundwater for their domestic indoor and outdoor water supply. The greatest volume of groundwater used every day is for agriculture, specifically for irrigation. In 2015, irrigation accounted for 69% of the total fresh groundwater withdrawals in the United States. For that year, California pumped the most groundwater for irrigation, followed by Arkansas, Nebraska, Idaho, Texas, and Kansas, in that order. Groundwater also is used as a supply for mining, oil and gas development, industrial processes, livestock, and thermoelectric power, among other uses. Congress generally has deferred management of U.S. groundwater resources to the states, and there is little indication that this practice will change. Congress, various states, and other stakeholders recently have focused on the potential for using surface water to recharge aquifers and the ability to recover stored groundwater when needed. Some see aquifer recharge, storage, and recovery as a replacement or complement to surface water reservoirs, and there is interest in how federal agencies can support these efforts. In the congressional context, there is interest in the potential for federal policies to facilitate state, local, and private groundwater management efforts (e.g., management of federal reservoir releases to allow for groundwater recharge by local utilities). -

Miami-Dade County Drainage and Canals Flood Complaint Form

MIAMI-DADE COUNTY DRAINAGE AND CANALS FLOOD COMPLAINT FORM Service Request # _____________ Complaint Date Time AM PM Resident/Complainant Name Address Telephone Nearest Street Intersection of Flooding or Location of Flooding Is this the first time you report this? Yes No If No, date PLEASE SELECT ONLY ONE (1) COMPLAINT TYPE AND ANSWER RELATED QUESTIONS FOR BETTER SERVICE Type of Complaint 302 Clogged Storm Drain Is the water on top of drain now? Yes No How long does it take for the water to drain? What is the exact location of the drain? Is the area a new development? Yes No Was there a recent drainage project in the area? Yes No 303 Standing Water (No Drain) How deep is the water? How hard did it rain? Light Moderate Heavy Is your property flooded? Yes No Is your property in a new development? Yes No Where is the nearest drain? Flooding/Standing Water (Localized) Is the water flooding the inside of your residence? Yes No Is the water in your driveway / swale? Yes No Is the water across the roadway? Yes No Is it affecting traffic? Yes No How long does the water remain after rainfall? Page 1 of 2 MIAMI-DADE COUNTY DRAINAGE AND CANALS FLOOD COMPLAINT FORM Canal Complaints Solid waste (floating debris, bottles, cans, etc.) present Aquatic vegetation overgrown Needs mowing / treating vegetation on canal bank Bank instability due to Erosion / Collapses are present Culvert cleaning needed Damaged culvert / Headwall Encroachment of Easement / Right of Way Cutting / trimming of trees on a canal Right of Way needed Damaged Guardrails / Fence Canal Signs damaged / down Other Other Nature of Complaint For more information, call (305) 372-6688 Page 2 of 2 . -

Irrigation Return Flow Or Discrete Discharge? Why Water Pollution from Cranberry Bogs Should Fall Within the Clean Water Act’S Npdes Program

GAL.HANSON.DOC 4/30/2007 10:08:35 AM IRRIGATION RETURN FLOW OR DISCRETE DISCHARGE? WHY WATER POLLUTION FROM CRANBERRY BOGS SHOULD FALL WITHIN THE CLEAN WATER ACT’S NPDES PROGRAM BY * ** ANDREW C. HANSON & DAVID C. BENDER Despite license plates proclaiming it as the “dairy state,” Wisconsin is the top cranberry producing state in the nation. Cranberry operations are unique in that they are agricultural operations that require vast quantities of water. Water discharged to lakes, wetlands, and rivers through ditches and canals during the production process can contain the phosphorus fertilizers and residues of pesticides that were applied during the growing season, which can cause serious water quality problems. Although the cranberry industry has not historically been subject to the Clean Water Act, cranberry bog discharges appear to fit squarely within the purview of the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program under that statute. In 2004, the Wisconsin attorney general filed a public nuisance lawsuit against a cranberry grower, alleging that the grower discharged bog water laced with phosphorus to the lake. However, provided that cranberry bog discharges do not fall within the “irrigation return flow” exemption from the Clean Water Act, the NPDES permit program may be a more cost-effective approach to addressing the water quality problems that can be caused by cranberry bog discharges. I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 340 II. POLLUTANT DISCHARGES FROM COMMERCIAL CRANBERRY PRODUCTION ...................... 342 III. STATE V. ZAWISTOWSKI AND THE ATTEMPT TO USE PUBLIC NUISANCE AUTHORITY TO CONTROL POLLUTANT DISCHARGES FROM CRANBERRY BOGS ................................... 345 IV. OVERVIEW OF THE CLEAN WATER ACT ........................................................................... 347 V. -

Acid Sulfate Soil Materials

Site contamination —acid sulfate soil materials Issued November 2007 EPA 638/07: This guideline has been prepared to provide information to those involved in activities that may disturb acid sulfate soil materials (including soil, sediment and rock), the identification of these materials and measures for environmental management. What are acid sulfate soil materials? Acid sulfate soil materials is the term applied to soils, sediment or rock in the environment that contain elevated concentrations of metal sulfides (principally pyriteFeS2 or monosulfides in the form of iron sulfideFeS), which generate acidic conditions when exposed to oxygen. Identified impacts from this acidity cause minerals in soils to dissolve and liberate soluble and colloidal aluminium and iron, which may potentially impact on human health and the environment, and may also result in damage to infrastructure constructed on acid sulfate soil materials. Drainage of peaty acid sulfate soil material also results in the substantial production of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O). The oxidation of metal sulfides is a function of natural weathering processes. This process is slow however, and, generally, weathering alone does not pose an environmental concern. The rate of acid generation is increased greatly through human activities which expose large amounts of soil to air (eg via excavation processes). This is most commonly associated with (but not necessarily confined to) mining activities. Soil horizons that contain sulfides are called ‘sulfidic materials’ (Isbell 1996; Soil Survey Staff 2003) and can be environmentally damaging if exposed to air by disturbance. Exposure results in the oxidation of pyrite. This process transforms sulfidic material to sulfuric material when, on oxidation, the material develops a pH 4 or less (Isbell 1996; Soil Survey Staff 2003). -

Drainage Water Management R

doi:10.2489/jswc.67.6.167A RESEARCH INTRODUCTION Drainage water management R. Wayne Skaggs, Norman R. Fausey, and Robert O. Evans his article introduces a series of the most productive in the world. Drainage needed. Drainage water management, or papers that report results of field ditches or subsurface drains (tile or plastic controlled drainage, emerged as an effec- T studies to determine the effec- drain tubing) are used to remove excess tive practice for reducing losses of N in tiveness of drainage water management water and lower water tables, improve traf- drainage waters in the 1970s and 1980s. (DWM) on conserving drainage water ficability so that field operations can be The practice is inherently based on the and reducing losses of nitrogen (N) to sur- done in a timely manner, prevent water fact that the same drainage intensity is face waters. The series is focused on the logging, and increase yields. Drainage is not required all the time. It is possible to performance of the DWM (also called also needed to manage soil salinity in irri- dramatically reduce drainage rates during controlled drainage [CD]) practice in the gated arid and semiarid croplands. some parts of the year, such as the winter US Midwest, where N leached from mil- Drainage has been used to enhance crop months, without negatively affecting crop lions of acres of cropland contributes to production since the time of the Roman production. Drainage water management surface water quality problems on both Empire, and probably earlier (Luthin may also be used after the crop is planted local and national scales. -

Troubleshooting Activated Sludge Processes Introduction

Troubleshooting Activated Sludge Processes Introduction Excess Foam High Effluent Suspended Solids High Effluent Soluble BOD or Ammonia Low effluent pH Introduction Review of the literature shows that the activated sludge process has experienced operational problems since its inception. Although they did not experience settling problems with their activated sludge, Ardern and Lockett (Ardern and Lockett, 1914a) did note increased turbidity and reduced nitrification with reduced temperatures. By the early 1920s continuous-flow systems were having to deal with the scourge of activated sludge, bulking (Ardem and Lockett, 1914b, Martin 1927) and effluent suspended solids problems. Martin (1927) also describes effluent quality problems due to toxic and/or high-organic- strength industrial wastes. Oxygen demanding materials would bleedthrough the process. More recently, Jenkins, Richard and Daigger (1993) discussed severe foaming problems in activated sludge systems. Experience shows that controlling the activated sludge process is still difficult for many plants in the United States. However, improved process control can be obtained by systematically looking at the problems and their potential causes. Once the cause is defined, control actions can be initiated to eliminate the problem. Problems associated with the activated sludge process can usually be related to four conditions (Schuyler, 1995). Any of these can occur by themselves or with any of the other conditions. The first is foam. So much foam can accumulate that it becomes a safety problem by spilling out onto walkways. It becomes a regulatory problem as it spills from clarifier surfaces into the effluent. The second, high effluent suspended solids, can be caused by many things. It is the most common problem found in activated sludge systems. -

Basic Elements of Ground-Water Hydrology with Reference to Conditions in North Carolina by Ralph C Heath

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Basic Elements of Ground-Water Hydrology With Reference to Conditions in North Carolina By Ralph C Heath U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Open-File Report 80-44 Prepared in cooperation with the North Carolina Department of Natural^ Resources and Community Development Raleigh, North Carolina 1980 United States Department of the Interior CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. W. Menard, Director For Additional Information Write to: Copies of this report may be purchased from: GEOLOGICAL SURVEY U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Services Section Post Office Box 2857 Branch of Distribution Box 25425, Federal Center Raleigh, North Carolina 27602 Denver, Colorado 80225 Preface Ground water is one of North Carolina's This report was prepared as an aid to most valuable natural resources. It is the developing a better understanding of the primary source-of water supplies in rural areas ground-water resources of the State. It and is also widely used by industries and consists of 46 essays grouped into five parts. municipalities, especially in the Coastal Plain. The topics covered by these essays range from However, its use is not increasing in proportion the most basic aspects of ground-water to the growth of the State's population and hydrology to the identification and correction economy. Instead, the present emphasis in of problems that affect the operation of supply water-supply development is on large regional wells. The essays were designed both for self systems based on reservoirs on large streams. study and for use in workshops on ground- The value of ground water as a resource not water hydrology and on the development and only depends on its widespread occurrence operation of ground-water supplies. -

Surface Water and Groundwater Interactions in Traditionally Irrigated Fields in Northern New Mexico, U.S.A

water Article Surface Water and Groundwater Interactions in Traditionally Irrigated Fields in Northern New Mexico, U.S.A. Karina Y. Gutiérrez-Jurado 1, Alexander G. Fernald 2, Steven J. Guldan 3 and Carlos G. Ochoa 4,* 1 School of the Environment, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA 5042, Australia; karina.gutierrez@flinders.edu.au 2 Water Resources Research Institute, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] 3 Sustainable Agriculture Science Center, New Mexico State University, Alcalde, NM 87511, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Animal and Rangeland Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-541-737-0933 Academic Editor: Ashok K. Chapagain Received: 18 December 2016; Accepted: 3 February 2017; Published: 10 February 2017 Abstract: Better understanding of surface water (SW) and groundwater (GW) interactions and water balances has become indispensable for water management decisions. This study sought to characterize SW-GW interactions in three crop fields located in three different irrigated valleys in northern New Mexico by (1) estimating deep percolation (DP) below the root zone in flood-irrigated crop fields; and (2) characterizing shallow aquifer response to inputs from DP associated with irrigation. Detailed measurements of irrigation water application, soil water content fluctuations, crop field runoff, and weather data were used in the water budget calculations for each field. Shallow wells were used to monitor groundwater level response to DP inputs. The amount of DP was positively and significantly related to the total amount of irrigation water applied for the Rio Hondo and Alcalde sites, but not for the El Rito site. -

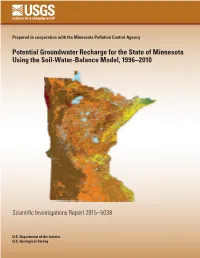

Potential Groundwater Recharge for the State of Minnesota Using the Soil-Water-Balance Model, 1996–2010

Prepared in cooperation with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Potential Groundwater Recharge for the State of Minnesota Using the Soil-Water-Balance Model, 1996–2010 Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Map showing mean annual potential recharge rates from 1996−2010 based on results from the Soil-Water-Balance model for Minnesota. Potential Groundwater Recharge for the State of Minnesota Using the Soil-Water- Balance Model, 1996–2010 By Erik A. Smith and Stephen M. Westenbroek Prepared in cooperation with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2015 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Smith, E.A., and Westenbroek, S.M., 2015, Potential groundwater recharge for the State of Minnesota using the Soil-Water-Balance model, 1996–2010: U.S.