Fourth Quarter Radio Coverage of Wilt Chamberlin's 100-Point Game (Philadelphia Warriors Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gether, Regardless Also Note That Rule Changes and Equipment Improve- of Type, Rather Than Having Three Or Four Separate AHP Ments Can Impact Records

Journal of Sports Analytics 2 (2016) 1–18 1 DOI 10.3233/JSA-150007 IOS Press Revisiting the ranking of outstanding professional sports records Matthew J. Liberatorea, Bret R. Myersa,∗, Robert L. Nydicka and Howard J. Weissb aVillanova University, Villanova, PA, USA bTemple University Abstract. Twenty-eight years ago Golden and Wasil (1987) presented the use of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for ranking outstanding sports records. Since then much has changed with respect to sports and sports records, the application and theory of the AHP, and the availability of the internet for accessing data. In this paper we revisit the ranking of outstanding sports records and build on past work, focusing on a comprehensive set of records from the four major American professional sports. We interviewed and corresponded with two sports experts and applied an AHP-based approach that features both the traditional pairwise comparison and the AHP rating method to elicit the necessary judgments from these experts. The most outstanding sports records are presented, discussed and compared to Golden and Wasil’s results from a quarter century earlier. Keywords: Sports, analytics, Analytic Hierarchy Process, evaluation and ranking, expert opinion 1. Introduction considered, create a single AHP analysis for differ- ent types of records (career, season, consecutive and In 1987, Golden and Wasil (GW) applied the Ana- game), and harness the opinions of sports experts to lytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to rank what they adjust the set of criteria and their weights and to drive considered to be “some of the greatest active sports the evaluation process. records” (Golden and Wasil, 1987). -

Harlem Globetrotters Adrian Maher – Writer/Director 1

Unsung Hollywood: Harlem Globetrotters Adrian Maher – Writer/Director 1 UNSUNG HOLLYWOOD: Writer/Director/Producer: Adrian Maher HARLEM GLOBETROTTERS COLD OPEN Tape 023 Ben Green The style of the NBA today goes straight back, uh, to the Harlem Globetrotters…. Magic Johnson and Showtime that was Globetrotter basketball. Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:04:17] The Harlem Globetrotters are arguably the best known sports franchise ….. probably one of the best known brands in the world. Tape 028 Kevin Frazier [16:13:32] The Harlem Globetrotters are …. a team that revolutionized basketball…There may not be Black basketball without the Harlem Globetrotters. Tape 001 Sweet Lou Dunbar [01:10:28] Abe Saperstein, he's only about this tall……he had these five guys from the south side of Chicago, they….. all crammed into ….. this one small car. And, they'd travel. Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:20:06] Abe was a showman….. Tape 033 Mannie Jackson (04:18:53) he’s the first person that really recognized that sports and entertainment were blended. Tape 018 Kevin “Special K” Daly [19:01:53] back in the day, uh, because of the racism that was going on the Harlem Globetrotters couldn’t stay at the regular hotel so they had to sleep in jail sometimes or barns, in the car, slaughterhouses Tape 034 Bijan Bayne [09:37:30] the Globetrotters were prophets……But they were aliens in their own land. Tape 007 Curly Neal [04:21:26] we invented the slam dunk ….., the ally-oop shot which is very famous and….between the legs, passes Tape 030 Mannie Jackson [01:21:33] They made the game look so easy, they did things so fast it looked magical…. -

2006 Media Guide.Indd

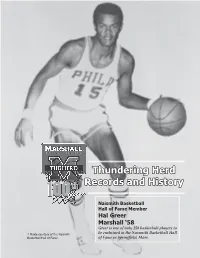

TThunderinghundering HerdHerd RRecordsecords aandnd HHistoryistory Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame Member Hal Greer Marshall ‘58 Greer is one of only 258 basketball players to * Photo courtesy of the Naismith be enshrined in the Naismith Basketball Hall Basketball Hall of Fame. of Fame in Springfi eld, Mass. 9977 r “Consistency,” Hal Hal Greer was named one of the NBA’s Top e Greer once told the e 50 Players in the late 90’s. He averaged 19 r Philadelphia Daily points, fi ve rebounds, and four assists in his G News. “For me, that was l NBA career. a the thing … I would like H Hal Greer to be remembered as a great, consistent player.” Over the course of rebounds and 4.4 assists per contest. With injuries limiting the 15 NBA seasons Schayes to 56 games, Greer took over the team’s scoring turned in by the slight, mantle. He ranked 13th in the NBA in scoring and ninth soft -spoken Hall of in free-throw percentage (.819). In the 1962 NBA All-Star Fame guard from West Game, Greer racked up a team-high nine assists - one more Virginia, consistency than the legendary Bob Cousy - and hauled in 10 rebounds, was indeed the thing. just two fewer than another legend, Bill Russell. Greer led He turned in quality the Nationals to the playoff s, where they fell to Warriors in performances almost every night, scoring 19.2 points the Eastern Division Semifi nals. per game during his career, playing in 1,122 games, and The smooth guard broke into the ranks of the top 10 racking up 21,586 points (14th on the all-time list). -

Baseball Men's College Basketball Women's College Basketball Nba Basketball Nhl Hockey Soccer

BASEBALL Georgetown at Creighton. (Same-day the season-series sweep of the Pelicans. Boston Red Sox at New York Yankees. Tape) (CC) (YES) T 10:30 pm Dallas last took all four games in a campaign from New Orleans in 2013- (CC) (YES) T 9:00 am WOMEN’S COLLEGE St. Louis Cardinals at New York Mets. 14. Luka Doncic (DAL) is averaging (Live) (CC) (ESPN) 8 1:00 pm BASKETBALL 28 points and 11.3 rebounds per game Mountain West Tournament, Final: against New Orleans in 2019-20. (Live) MEN’S COLLEGE Teams TBA. (Live) (SPTCBS) 11:00 pm (ESPN) 8 9:30 pm BASKETBALL NBA BASKETBALL NHL HOCKEY Xavier at Providence. (Live) (CC) (FS1) Indiana Pacers at Milwaukee Bucks. Buffalo Sabres at Winnipeg Jets. 6:30 pm The Bucks host the Pacers. Milwaukee (MSGPL) : 8:00 am, 3:00 pm Texas A&M at Auburn. (Live) (ESPN2) allowed just 86 points per game in their St. Louis Blues at New York Rangers. 9 7:00 pm first two 2019-20 meetings, but Indiana (MSG) V 9:30 am, 1:00 pm Northeast Tournament — Mount St. prevailed 118-111 on Feb. 12. Malcolm Mary’s at Sacred Heart. (Live) (SNY) Brogdon (IND) is posting 13.5 ppg and Philadelphia Flyers at Washington 7:00 pm 11.5 assists per game versus his old club Capitals. (Live) (NBCS) 7:00 pm Niagara at Siena. (Live) (WEDG) $ this season. (Live) (ESPN) 8 7:00 pm Anaheim Ducks at Colorado Ava- 7:00 pm Utah Jazz at New York Knicks. From lanche. -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of August 1, 2012 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) LEAGUE UPDATE: For the 2011-12 season, the following teams are no longer members of the ABA: Atlanta Experience, Chi-Town Bulldogs, Columbus Riverballers, East Kentucky Energy, Eastonville Aces, Flint Fire, Hartland Heat, Indiana Diesels, Lake Michigan Admirals, Lansing Law, Louisiana United, Midwest Flames Peoria, Mobile Bat Hurricanes, Norfolk Sharks, North Texas Fresh, Northwestern Indiana Magical Stars, Nova Wonders, Orlando Kings, Panama City Dream, Rochester Razorsharks, Savannah Storm, St. Louis Pioneers, Syracuse Shockwave. Team: ABA-Canada Revolution Principal Owner: LTD Sports Inc. Team Website Arena: Home games will be hosted throughout Ontario, Canada. Team: Aberdeen Attack Principal Owner: Marcus Robinson, Hub City Sports LLC Team Website: N/A Arena: TBA © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Alaska 49ers Principal Owner: Robert Harris Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School UPDATE: Due to the success of the Alaska Quake in the 2011-12 season, the ABA announced plans to add another team in Alaska. The Alaska 49ers will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012-13 season. The 49ers will compete in the Pacific Northwest Division. Team: Alaska Quake Principal Owner: Shana Harris and Carol Taylor Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School Team: Albany Shockwave Principal Owner: Christopher Pike Team Website Arena: Albany Civic Center Facility Website UPDATE: The Albany Shockwave will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012- 13 season. -

Basketball and Philosophy, Edited by Jerry L

BASKE TBALL AND PHILOSOPHY The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will il- luminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popu- lar culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigorated by increased scholarly interest in the inter- section of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical concepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and exam- ine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham BASKETBALL AND PHILOSOPHY THINKING OUTSIDE THE PAINT EDITED BY JERRY L. WALLS AND GREGORY BASSHAM WITH A FOREWORD BY DICK VITALE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication -

Indiana Pacers Vs New York Knicks Live Stream

1 / 4 Indiana Pacers Vs New York Knicks Live Stream NBA Live: Pacers vs Hornets Live Stream Reddit Free Charlotte Hornets vs Indiana Pacers will happen in NBA Play-in tournament. New York is 31-27 overall .... Aug 22, 2020 — No time like the present for the Indiana Pacers to show up. The NBA's Eastern Conference No. 4 seed cannot afford another unsatisfying .... ... To Elevate Knicks · MSG PM. Jul 12, 2021. Video Player is loading. Play Video. Play. Mute. Current Time 0:00. /. Duration -:-. Loaded: 0%. Stream Type LIVE.. Free Picks » NBA Picks » Cleveland Cavaliers vs Indiana Pacers Prediction, 12/31/2020 ... though the Cavaliers lost a home game to the New York Knicks in their last outing. ... You can also live stream the same via the NBA League Pass.. Learn how to watch Indiana Pacers vs New York Knicks 3 April 2012 stream online, see match results and teams h2h stats at Scores24.live!. May 20, 2021 — The Washington Wizards will host the Indiana Pacers on Thursday night for the right to be eighth playoff seed in the Eastern Conference.. Jan 16, 2014 — New York Knicks vs Indiana Pacers Live Stream: Watch Online Free 7 ET Thursday Night, TNT – Paul George Looking To Give His All Against .... Oct 19, 2018 — Brooklyn Nets vs. New York Knicks: Live stream, TV, injury report ... Meanwhile, the New York Knicks are looking for their first 2-0 start to a season since ... Brooklyn: at Indiana, Saturday; at Cleveland, Wednesday; at New Orleans, Oct. 26 ... Chicago Bulls · Cleveland Cavs · Detroit Pistons · Indiana Pacers ... -

Corporate Social Responsibility in Professional Sports: an Analysis of the NBA, NFL, and MLB

Corporate Social Responsibility in Professional Sports: An Analysis of the NBA, NFL, and MLB Richard A. McGowan, S.J. John F. Mahon Boston College University of Maine Chestnut Hill, MA, USA Orono, Maine, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an area of organizational study with the potential to dramatically change lives and improve communities across the globe. CSR is a topic with extensive research in regards to traditional corporations; yet, little has been conducted in relation to the professional sports industry. Although most researchers and professionals have accepted CSR has a necessary component in evaluating a firm‟s performance, there is a great deal of variation in how it should be applied and by whom. Professional sports franchises are particularly interesting, because unlike most corporations, their financial success depends almost entirely on community support for the team. This paper employs a mixed-methods approach for examining CSR through the lens of the professional sports industry. The study explores how three professional sports leagues, the National Basketball Association (NBA), the National Football Association (NFL), and Major League Baseball (MLB), engage in CSR activities and evaluates the factors that influence their involvement. Quantitative statistical analysis will include and qualitative interviews, polls, and surveys are the basis for the conclusions drawn. Some of the hypotheses that will be tested include: Main Research Question/Focus: How do sports franchises -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

Southern Miss Men's Basketball Southern Miss Combined Team Statistics (As of Dec 21, 2017) All Games

Southern Miss Men’s Basketball David Cohen, SOUTHERN MISS GOLDEN EAGLES (7-5, 0-0 C-USA) Director of Communications Head Coach: Doc Sadler (Arkansas, 1982) • 601-266-6240 (o) Record at Southern Miss: 27-68 (fourth season), Career Record: 176-175 (12th season) • 817-739-6585 (c) • [email protected] MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (10-1, 0-0 SEC) • @DavidECohen_ Head Coach: Ben Howland (Weber State, 1979) Southern Miss Athletics Record at MSU: 40-34 (third season) Career Record: 441-240 (22nd season) • 118 College Drive #5017 • Hattiesburg, Miss. 39406-0001 Game Information Golden Eagle Notes Date / Time: – The Golden Eagles are closing out their non-conference campaign with two of their toughest opponents yet over a three-day Saturday, Dec. 23 6 p.m. CT stretch, first falling to No. 24 Florida State (first game against a ranked opponent since No. 9 Louisville on Nov. 29, 2013) on Thursday. Site / Venue (Capacity): Jackson, Miss. Mississippi Coliseum (6,812) – Southern Miss’ recent four-game winning streak was its longest of the Doc Sadler era, and the squad is already two wins away from matching its most in four years since inheriting NCAA sanctions. The Golden Eagles have faced three defending conference champs this season, and among that mark is a halftime lead at defending Big Ten champ Michigan and an 18-point win over Sun TV: N/A Belt champ Troy. Talent: – Southern Miss ranks No. 7 in the nation for fewest turnovers per game (9.8) and No. 12 for assist-turnover ratio (1.56), as well as Radio: Southern Miss IMG Sports Network sixth for turnover margin (+5.9). -

Becoming the Globetrotters Have You Ever the New York Dreamed of Being Globetrotters 1930- 31 Team

© 2014 Universal Uclick 88 Years of Entertaining from The Mini Page © 2014 Universal Uclick Becoming the Globetrotters Have you ever The New York dreamed of being Globetrotters 1930- 31 team. Coach Abe a professional Saperstein is on the left. basketball player? Players, standing left to Today, men and right, are Walter “Toots” women of nearly Wright, Byron Long, Inman every nationality Jackson and William “Kid” An early basketball Oliver. Al “Runt” Pullins is compete in sitting down. professional leagues all over the world. Saperstein later renamed But the National Basketball the team the Harlem Association (NBA) wasn’t formed until Globetrotters. He thought 1949. In the 1920s and 1930s, teams the reference to the New York neighborhood would in the United States traveled from let people know that town to town without the structure of the team was African- a league, playing other teams for the American and would seem entertainment of the townspeople. This exotic to audiences in smaller cities. type of play is called barnstorming. photo courtesy Harlem Globetrotters One special team formed in 1926 in Separate teams White players only Chicago and later became known as Some of the best early basketball Many early barnstorming teams the Harlem Globetrotters. This week, teams were segregated, or divided by did not allow African-American The Mini Page learns more about this their race or ethnic background. For players. A group of friends who had historical barnstorming basketball team example, teams of Jewish, Irish, Swedish graduated from Chicago’s all-black that’s still entertaining fans today. and Chinese players barnstormed on Wendell Phillips High School got the East Coast and beyond. -

The Ranking Prediction of NBA Playoffs Based on Improved Pagerank Algorithm

Hindawi Complexity Volume 2021, Article ID 6641242, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6641242 Research Article The Ranking Prediction of NBA Playoffs Based on Improved PageRank Algorithm Fan Yang 1 and Jun Zhang2 1School of Management, Xi’an Polytechnic University, Xi’an 710048, Shaanxi, China 2Xi’an Wannian Technology Industry Co., Ltd., Xi’an 710038, Shaanxi, China Correspondence should be addressed to Fan Yang; [email protected] Received 23 December 2020; Revised 27 January 2021; Accepted 3 February 2021; Published 16 February 2021 Academic Editor: Wei Wang Copyright © 2021 Fan Yang and Jun Zhang. *is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. It is of great significance to predict the results accurately based on the statistics of sports competition for participants research, commercial cooperation, advertising, and gambling profit. Aiming at the phenomenon that the PageRank page sorting algorithm is prone to subject deviation, the category similarity between pages is introduced into the PageRank algorithm. In the PR value calculation formula of the PageRank algorithm, the factor W(u, v) between pages is added to replace the original Nu (the number of links to page u). In this way, the content category between pages is considered, and the shortcoming of theme deviation will be improved. *e time feedback factor in the PageRank-time algorithm is used for reference, and the time feedback factor is added to the first improved PR value calculation formula. Based on statistics from 1230 games during the NBA 2018-2019 regular season, this paper ranks the team strength with improved PageRank algorithm and compares the results with the ranking of regular- season points and the result of playoffs.