Harvest Mouse Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sussex Wildlife Trust

s !T ~ !I ~ !f ~ !I THE SUSSEX RECORDER !f ~ !I Proceedings from the !l Biological Recorders' Seminar ?!I held at !!I the Adastra Hall, Hassocks ~ February 1996. !I ~ !I Compiled and edited by Simon Curson ~ ~ ~ !I ~ !I ~ Sussex Wildlife Trust :!f Woods Mill Sussex ~ ·~ Henfield ,~ ~ West Sussex Wildlife ;~ BN5 9SD TRUSTS !f ~ -S !T ~ ~ ~ !J ~ !J THE SUSSEX RECORDER !f !I !I Proceedings from the !I Biological Recorders' Seminar ?!I held at ~ the Adastra Hall, Hassocks ~ February 1996. !I ~ !I Compiled and edited by Simon Curson ~ ~ "!I ~ ~ !I Sussex Wildlife Trust ~ Woods Mill Sussex ~ ·~ Benfield ~ -~ West Sussex ~ Wildlife BN5 9SD TRUSTS ~ ~ .., ~' ~~ (!11 i JI l CONTENTS f!t~1 I C!! 1 Introduction 1 ~1 I ) 1 The Environmental Survey Directory - an update 2 I!~ 1 The Sites of Nature Conservation Importance (SNCI) Project 4 f!11. I The Sussex Rare Species Inventory 6 I!! i f!t I Recording Mammals 7 • 1 I!: Local Habitat Surveys - How You can Help 10 I!~ Biological Monitoring of Rivers 13 ~! Monitoring of Amphibians 15 I!! The Sussex SEASEARCH Project 17 ~·' Rye Harbour Wildlife Monitoring 19 r:! Appendix - Local Contacts for Specialist Organisations and Societies. 22 ~ I'!! -~ J: J~ .~ J~ J: Je ISBN: 1 898388 10 5 ,r: J~ J Published by '~i (~ Sussex Wildlife Trust, Woods Mill, Henfield, West Sussex, BN5 9SD .~ Registered Charity No. 207005 l~ l_ l~~l ~-J'Ii: I ~ ~ /~ ~ Introduction ·~ !J Tony Whitbread !! It is a great pleasure, once again, to introduce the Proceedings of the Biological !l' Recorders' Seminar, now firmly established as a regular feature of the biological year in Sussex. -

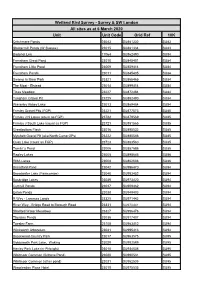

Unit Unit Code Grid Ref 10K Wetland Bird Survey

Wetland Bird Survey - Surrey & SW London All sites as at 6 March 2020 Unit Unit Code Grid Ref 10K Critchmere Ponds 23043 SU881332 SU83 Shottermill Ponds (W Sussex) 23015 SU881334 SU83 Badshot Lea 17064 SU862490 SU84 Frensham Great Pond 23010 SU845401 SU84 Frensham Little Pond 23009 SU859414 SU84 Frensham Ponds 23011 SU845405 SU84 Swamp in Moor Park 23321 SU865465 SU84 The Moat - Elstead 23014 SU899414 SU84 Tices Meadow 23227 SU872484 SU84 Tongham Gravel Pit 23225 SU882490 SU84 Waverley Abbey Lake 23013 SU869454 SU84 Frimley Gravel Pits (FGP) 23221 SU877573 SU85 Frimley J N Lakes (count as FGP) 23722 SU879569 SU85 Frimley J South Lake (count as FGP) 23721 SU881565 SU85 Greatbottom Flash 23016 SU895532 SU85 Mytchett Gravel Pit (aka North Camp GPs) 23222 SU885546 SU85 Quay Lake (count as FGP) 23723 SU883560 SU85 Tomlin`s Pond 23006 SU887586 SU85 Rapley Lakes 23005 SU898646 SU86 RMA Lakes 23008 SU862606 SU86 Broadford Pond 23042 SU996470 SU94 Broadwater Lake (Farncombe) 23040 SU983452 SU94 Busbridge Lakes 23039 SU973420 SU94 Cuttmill Ponds 23037 SU909462 SU94 Enton Ponds 23038 SU949403 SU94 R Wey - Lammas Lands 23325 SU971442 SU94 River Wey - Bridge Road to Borough Road 23331 SU970441 SU94 Shalford Water Meadows 23327 SU996476 SU94 Thursley Ponds 23036 SU917407 SU94 Tuesley Farm 23108 SU963412 SU94 Winkworth Arboretum 23041 SU995413 SU94 Brookwood Country Park 23017 SU963575 SU95 Goldsworth Park Lake, Woking 23029 SU982589 SU95 Henley Park Lake (nr Pirbright) 23018 SU934536 SU95 Whitmoor Common (Brittons Pond) 23020 SU990531 SU95 Whitmoor -

Chobham Common and the Martian Landing Site

1 Chobham Common and the Martian Landing Site Sunningdale station - Chobham Common - Stanners Hill - Anthonys - Horsell Common - Woking station Length: 8 ¾ miles (14.1km) Underfoot: There are a handful of Useful websites: The route potentially muddy points on Chobham crosses Chobham Common National Common and in woodland, but this walk is Nature Reserve, passes the overwhelmingly firm underfoot and easy remarkable McLaren Technology going. Centre and Horsell Common. Nearing Woking it passes the Lightbox Museum Terrain: There are no significant climbs and and Gallery. just one brief, relatively steep descent to Albury Bottom. Getting home: Woking has very frequent South West Trains services to London Maps: 1:50,000 Landranger 175 Reading & Waterloo (29-49 mins) - as many as 14 Windsor and 186 Aldershot & Guildford; per hour. 1:25,000 Explorer 160 Windsor, Weybridge & Bracknell and 145 Guildford & Farnham Around half the services call at Clapham (NB: only the last mile into Woking is on Junction (19-39 mins) for connections to Explorer 145. You should be fine just using London Victoria and London Overground. 160 and the directions below). Fares: The cheapest option is to purchase Getting there: South West Trains operate an off-peak day return to Woking for two trains per hour from London Waterloo £12.80 (£6.40 child, £8.45 railcard) and a to Sunningdale (47 mins) via Clapham Virginia Water - Sunningdale single to Junction (39 mins) for London Overground cover the last section of the outward and connections from London Victoria and journey for £2.60 (£1.30 child, £1.70 Richmond (31 mins) for District line. -

Bulletin N U M B E R 2 8 9 December 1994/January 1995

Registered Charity No: 272098 ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Guildford 32454 Bulletin N u m b e r 2 8 9 December 1994/January 1995 COUNCIL NEWS Guildford Castle and Royal Palace Training Excavation At the barbecue on the final day two sheep are roasted in the traditional manner by refugees from Bosnia, now living in Surrey OBITUARY M i s s M A B e c k Jill Beck died after a short Illness on 17 August 1994, the day after her seventy seventh birthday. As Archlvlst-ln-Charge she presided over Guildford Muniment Room from January 1971 (when Dr Enid Dance retired) until her own retirement In 1982. The greater part of her working life was passed In Guildford, where her first job as an archivist had brought her to work (for six months that became three years, 1950-1953) in the Muniment Room, cataloguing the Loseley MSS on behalf of the Historical Manuscripts Commission. After eight years organising the archives at Petworth House she then returned to Guildford as assistant archivist in 1961. Jill was modest about her own achievements and would lay claim only to having a good memory. She brought to her archival tasks many other advantages: a well organised mind, the highest standards of scholarship and a natural grace of style. All those who used the Muniment Room during the twenty five years that she worked there will testify to her apparently almost infinite patience and helpfulness, and all present and future historians of Surrey are indebted to her for the excellence of the lists and indexes she produced. -

Family Off-Road Cycle Route

Norbury Park 2007:Norbury Park Leaflet 22/9/09 15:48 Page 1 Access through the barrier and go down the hill. Take care if it’s wet as the slope can become slippery. At the bottom kissing gate turn left and walk along the field headland, then turn right past the large beech trees down towards the railway. Family Off-road Cycle Route 1 This trail is approximately 7km (4 /2 miles) long, follows a firm surface and will 1 take about 1 /4 hours, it is waymarked by posts with a cycle symbol. The trail is also suitable for the more robust type of off-road pushchair and four-wheel disabled buggy/scooter. WARNING: This trail uses a short section of public road, the rest is within Norbury Park. Be prepared to meet farm vehicles and timber lorries. Back Drive possesses speed humps. Start from Fetcham car park (height restriction at entrance) take the track in front of the information board. The woodland on your right is called The Hazels and in the past has been coppiced regularly - cut down to just above ground level and allowed to regrow - to provide bean and pea sticks. In springtime the woodland floor is covered with primroses, which attract numerous feeding insects. The woodland in the distance on your left is known as Fetcham Downs. Some 60 -100 years ago much of this area was open grassland but left unmanaged it has gradually reverted to woodland. Longcut Barn on your left was once used as a holding pen for the sheep which used to graze the downland. -

English Nature Research Report

LOCAL'REGIONAL BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLANS Plan name c. "K;IOL'JJ:: Ref. No Area $,:rev countv Regton CC.JTH LAST Organisations involved SJrrey WT Coordinating Surrey County Council Coordinating E-gltsh Nature Funding ~5x3 source of information 7#*/AG Source of information Eiv Age C:k WWF-UK and Herpetological Consewation Trust Purpose Outline long term (50 yrs) vision for arEa set targets for existing work Identify priorities Coordinate partners Audience Local CouncillorIdecisionmakers Timescale First draft Contact Jtil Barton IDebbie Wicks Surrey Wildlife Trust 01 483 488055 -~"__--_I-___"___- I --_I--.-- - Plan name Unknown Ref. No. Area Greater London Region SOUTH EAST Organisations involved Role London Wildlife Trust Coordinating London Ecology URlt Coordinating ENIEA Coordinating 3TCVIRSPB Coordinating WTINat.His. Soc. Source of information Tne above make up the steering group together vvlth another Six Purpose Outline long term (50 yrs) vision for area Set targets for existing work Identify priorities Coordinate partners Audience General public Conservation staff in paltnerirelated organisations Local CouncillorIdecisionmakers Mern bersivolunteers Timescale Unknown Contact Ralph Gaines London Wildlife Trust 0171 278 661213 __-______-_I ~ ---^_---_--__-+_-- +"." ---I--7-_-_+ 01 '20198 Page 27 LOCAURECIONAL BlODlVERSlTY ACTION PLANS Plan name UnKfiOVIC Ref. No. Area ilmpsnire county Region SCUTH EAST Organisations involved Role Hampshire Wildlife Trust Caord!nating Hampshire County Council Coordinating Local Authorities Funding Engllsh Nature ' Env Age Source of information RSPB Source of information CLA NFU CPRE.FA.FE Purpose Set targets for existing work Identify priorities Coordinate partners Audience General public Local CouncillorIdecision makers Timescale First drafi Audit planned summer 1998 Contact Patrick Cloughley Hampshire and IOWWildlife Trust 01 703 61 3737 -___ , _____.__x """ ____---I_--_____-__I ___-_I ---_ ~ ".... -

Biodiversity Net Gain. Good Practice Principles for Development

CIRIA C776b London, 2019 Biodiversity net gain. Good practice principles for development Case studies Tom Butterworth WSP Julia Baker Balfour Beatty Rachel Hoskin Footprint Ecology Griffin Court, 15 Long Lane, London, EC1A 9PN Tel: 020 7549 3300 Fax: 020 7549 3349 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ciria.org 12 Creation of Priest Hill Nature Reserve, Ewell, Surrey Details Organisations Surrey Wildlife Trust, Combined Counties Properties and CALA Homes Contact [email protected] / [email protected] 12.1 PROJECT SUMMARY At Priest Hill, Ewell a new 34 hectare nature reserve has been delivered through planning gain alongside a 1.7 hectare development of 15 residential homes from abandoned playing fields plus some previously- developed land. Before purchase the site had been largely abandoned inviting fly-tipping, arson and other urban fringe problems, while the potential diversity of its habitats (rank semi-improved grassland and scrub) was in decline. The original developer, Combined Counties Properties, Figure 12.1 Priest Hill nature reserve, Ewell, Surrey funded much of the priority habitat restoration and creation as well as providing a site manager’s house and maintenance base, as a significant BNG. Ownership of the reserve and associated buildings was transferred to Surrey Wildlife Trust ahead of development of the remainder of the site, marketed later by CALA Homes. Throughout the process, the Trust worked closely with the developers and the LPA, Epsom & Ewell Borough Council, to ensure the full potential of the site was realised. 12.2 ISSUES The site is located within the green belt so there was local resistance to any development, especially the policy-recommended affordable housing allocation (which was subsequently waived). -

Biodiversity Opportunity Areas: the Basis for Realising Surrey's Local

Biodiversity Opportunity Areas: The basis for realising Surrey’s ecological network Surrey Nature Partnership September 2019 (revised) Investing in our County’s future Contents: 1. Background 1.1 Why Biodiversity Opportunity Areas? 1.2 What exactly is a Biodiversity Opportunity Area? 1.3 Biodiversity Opportunity Areas in the planning system 2. The BOA Policy Statements 3. Delivering Biodiversity 2020 - where & how will it happen? 3.1 Some case-studies 3.1.1 Floodplain grazing-marsh in the River Wey catchment 3.1.2 Calcareous grassland restoration at Priest Hill, Epsom 3.1.3 Surrey’s heathlands 3.1.4 Priority habitat creation in the Holmesdale Valley 3.1.5 Wetland creation at Molesey Reservoirs 3.2 Summary of possible delivery mechanisms 4. References Figure 1: Surrey Biodiversity Opportunity Areas Appendix 1: Biodiversity Opportunity Area Policy Statement format Appendix 2: Potential Priority habitat restoration and creation projects across Surrey (working list) Appendices 3-9: Policy Statements (separate documents) 3. Thames Valley Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (TV01-05) 4. Thames Basin Heaths Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (TBH01-07) 5. Thames Basin Lowlands Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (TBL01-04) 6. North Downs Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (ND01-08) 7. Wealden Greensands Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (WG01-13) 8. Low Weald Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (LW01-07) 9. River Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (R01-06) Appendix 10: BOA Objectives & Targets Summary (separate document) Written by: Mike Waite Chair, Biodiversity Working Group Biodiversity Opportunity Areas: The basis for realising Surrey’s ecological network, Sept 2019 (revised) 2 1. Background 1.1 Why Biodiversity Opportunity Areas? The concept of Biodiversity Opportunity Areas (BOAs) has been in development in Surrey since 2009. -

Butterfly Conservation

Get involved • Join Butterfly Conservation and help save butterflies and moths • Visit the website and subscribe to our Facebook and Twitter feeds Butterfly Conservation • Record your sightings and submit them, e.g. using the iRecord Surrey & SW London Branch Butterflies smartphone app • Join a field trip to see butterflies in their natural habitat • Take part in the Big Butterfly Count in July-August • Help the Branch survey for butterflies and moths • Have fun volunteering and get fit on a conservation work party • Help publicise the Branch’s work at public events • Walk a transect to monitor butterflies through the season • Take part in the Garden Moths Scheme • Get involved in helping to run the Branch © Bill Downey Bill © Conservation work party for the Small Blue Stepping Stones project About Butterfly Conservation Butterfly Conservation is the UK charity dedicated to saving butterflies and moths, which are key indicators of the health of our environment. Butterfly Conservation improves landscapes for butterflies and moths, creating a better environment for us all. Join at www.butterfly-conservation.org The Surrey & SW London Branch area covers the present county of Surrey (excluding Spelthorne) and the London Boroughs of Richmond, Wandsworth, Lambeth, Southwark, Kingston, Merton, Sutton and Croydon. See www.butterfly-conservation.org/surrey or phone 07572 612722. Butterfly Conservation is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England (2206468). Tel: 01929 400 209. Registered Office: Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Dorset, BH20 5QP. Charity registered in England & Wales (254937) and in Scotland (SCO39268). Published by the Surrey & SW London Branch of Butterfly Conservation © 2018 Where to go What we do Everyone loves butterflies and we Monitoring and surveying are fortunate that 41 species can Volunteers walk weekly routes, be seen in Surrey, along with 500 called “transects”, on around 100 moths and 1,100 micro-moths. -

Trustees' Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 March 2019

Registered Charity Number: 208123 Registered Company Number: 00645176 SURREY WILDLIFE TRUST TRUSTEES’ ANNUAL REPORT AND CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2019 SURREY WILDLIFE TRUST TRUSTEES’ REPORT AND CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2019 _________________________________________________________________________________ Contents TRUSTEES’ ANNUAL REPORT: FOREWORD FROM THE CHAIRMAN, CHRIS WILKINSON ..................................................................... 2 OVERVIEW FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE, SARAH JANE CHIMBWANDIRA ................................. 3 STRATEGIC REPORT .............................................................................................................................................. 5 LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ...................................................................................... 17 STRUCTURE, GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT ................................................................................ 18 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW ................................................................................. 19 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT TO THE MEMBERS OF SURREY WILDLIFE TRUST .............. 20 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES INCORPORATING AN INCOME AND EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT .......................................................................................................................................... 23 BALANCE SHEETS ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Overview of SWT Plans to Deal with Ash

West Surrey Badger Group, Surrey Dormouse Group and Surrey Bat Group views on the Surrey Wildlife Trust’s plan for Ash Dieback on their countryside estate. Context Ash Dieback (ADB) is a disease of ash trees caused by the fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus originating in Asia. It appeared first in Eastern Europe in about 1992 and has since moved westward, reaching the UK in 2012. It is now found across the entire UK, including Surrey, where most ash trees are believed to be infected. Ash (Fraxinus excelsior) is the third most common tree in England, and is found on most Surrey sites. ADB causes defoliation, crown dieback, and in many cases, leads to the death of the tree. The questions this raises are • Will all ash trees become infected? This seems very likely – most are probably already infected. • Will all ash trees show symptoms? Many will, although not necessarily all, and the severity will vary. Established, mature trees in mixed woodland seem least affected. • Will all ash trees die? This is uncertain. Across Europe, based on studies over the past 20 years, maximum mortality figures so far for natural woodland (as against plantations) seem to be around 70% (Ref 1). • How quickly will this happen? Again this is uncertain. It varies according to local conditions, the state and make-up of the woodland and the weather. Given around 30% of trees are still alive after up to 20 years, it won’t happen all at once, but trees are already showing symptoms in Surrey. A study in France & Belgium showed that for trees >25cm, annual mortality reached 3.2% after 8-9 years of pathogen presence, while for trees >5cm but<25cm it was ~10%. -

Version 3 | July 2018 Contents

Volunteer handbook Version 3 | July 2018 Contents 3. Welcome to Surrey Wildlife Trust 4. About Surrey Wildlife Trust 5. What is volunteering 6. Volunteer roles & responsibilities 7. Important information 9. The social aspect 10. Map of managed sites 11. Site list Contact details The Volunteer Development Team, Surrey Wildlife Trust, School Lane Pirbright, Surrey GU24 0JN © Surrey Wildlife Trust 2018 Registered Charity No 208123 Welcome to Surrey Wildlife Trust! Now you have signed up to volunteering, you will be part of a network of volunteers who help the Trust to make a real difference for nature You could be... SAVING THREATENED HABITATS… SURVEYING PROTECTED SPECIES INSPIRING A THE NEXT GENERAtion… RAISING AWARENESS IN YOUR LOCAL COMMUNITY Volunteers are an important and valued part of Surrey Wildlife Trust (SWT) and this is your chance to make a real contribution to local conservation. We hope that you enjoy volunteering with us and feel part of our team. Founded by volunteers in 1959 the same ideals still remain at the core of the organisation today, with volunteers working alongside our staff in just about every aspect of the Trust. The partnership between the Trust and its volunteers has enabled us to advance nature conservation and awareness in the county and we are committed to continuing this vital work. This handbook has been produced by the Volunteer Development team and includes the main information you’ll need to know about volunteering with Surrey Wildlife Trust. Welcome and thank you for your support! Surrey Wildlife Trust Volunteer Handbook | 3 About Surrey Wildlife Trust Surrey Wildlife Trust is committed to helping wildlife to survive and thrive across the county Surrey Wildlife Trust is one of 46 Wildlife Trusts working across the UK.