Reluctant Readers in Middle School: Successful Engagement with Text Using the E- Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Women's Performances of Sexuality

“DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performances of Sexuality Copyright 2012 Evleen Michelle Nasir “DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Harry Berger Alfred Bendixen Head of Department, Judith Hamera August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performance of Sexuality. (August 2012) Evleen Michelle Nasir, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen There is a discursive formation of incapability that surrounds senior women’s sexuality. Senior women are incapable of reproduction, mastering their bodies, or arousing sexual desire in themselves or others. The senior actresses’ I explore in the case studies below insert their performances of self and their everyday lives into the large and complicated discourse of sex, producing a counter-narrative to sexually inactive senior women. Their performances actively embody their sexuality outside the frame of a character. This thesis examines how senior actresses’ performances of sexuality extend a discourse of sexuality imposed on older woman by mass media. These women are the public face of senior women’s sexual agency. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Juvenile Series Fiction Series Title Series Description Age/ Grd

Juvenile Series Fiction Series Title Series Description Age/ Grd. Genre Amy and her brother Dan have chosen to participate in a perilous tresure hunt that was created by their deceased Aunt Grace. They must 39 Clues decipher 39 clues to find the treasure. Grds. 4-6 Mystery Dink, Josh and Ruth Rose are friends. Together they solve mysteries that begin with a letter of the alphabet. The mysteries are simple enough that readers can collect clues and solve them along A-Z Mysteries with the characters. Grds. K-3 Mystery Who is Charlie Small? There are only his journals to describe his adventures. Did this 8-year-old really ride a rhino, defeat a crocodile, and lead the Adventures ofCharlie Small gorillas? Grds. 3-5 Humor/Adv Amber Brown is a third grader when the series begins. Through the series Amber uses humor to face the trials of growing up, her parent's divorce Amber Brown and her mother's remarriage. Grds. 2-4 Humor The stories portray strong young girls and women growing up in the United States during different American Girl time periods. Grds. 2-5 Fam. Life Fans of American Girl Books will enjoy reading about their favorite characters in these mysteries. Factual information relevant to the story is American Girl Mysteries appended. Grds. 2-5 Mystery Mandy's parents are veterinarians and she sometimes helps out at their animal hospital. Mandy and her friends try to help find homes for Animal Ark stray pets. Grds. 3-5 Real Life Marc Brown's Arthur Books continue in this series for the intermediate chapter book reader. -

SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 , |FL1 SECTION SECTION SECTION SECTION Table of TABLE OF

11 th ANNUAL SECTION SECTION CONTENT sunscreenCONTENT FILM FESTIVAL Presented by 2016 PROGRAM GUIDE SOUTH BAY - LOS ANGELES April 28 - May 1 ST. PETERSBURGSUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 , |FL1 SECTION SECTION SECTION SECTION Table of OF TABLE WHEN ALL OF YOU GET CONTENTS CONTENT BIG AND FAMOUS AND CONTENTS Welcome 4 CONTENT Box Office Information 5 Box Offices GO TO HOLLYWOOD Tickets & Passes Special Events Workshops PARTIES AND DRIVE Awards Ceremony & After Party AD Festival Schedule 6 - 7 Workshops & Panels 8 - 10 FLASHY CARS, Special Events Schedule 12 Opening Night Gala 13 Celebrity Guests 14 JUSTPAGE REMEMBER, Special Guests 15 - 20 Film Info and Schedule 22 - 48 Thursday • April 28 23 • 24 YOU’LL GET MORE FOR Friday • April 29 25 • 31 Saturday • April 30 32 • 40 YOUR MOVIE HERE. Sundauy • May 1 41 • 47 Sponsors 49 - 51 Get more for your movie here. PROUD SPONSOR OF THE SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2 SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 | 3 Sunscreen Film Festival ad 5x8.indd 1 4/7/2016 4:24:18 PM BOX OFFICE INFORMATION BOX OFFICE Regular Box Office opens Thursday, April 28 at the primary venue: American Stage, 163 3rd Street, North., St. Petersburg, Florida 33701. WELCOME BOX OFFICES INFORMATION Online Book tickets anytime day or night! Visit our website: www.SunscreenFilmFestival.com Festival Office American Stage. 163 3rd Street, North., St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 SOUTH BAY - LOS ANGELES Telephone Call (727) 259-8417 • Hours: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm • Monday - Sunday Visa and Mastercard, AMEX, Discover accepted at box office (at door) and Paypal accepted for advanced, online tickets and pass purchases. -

Alice Syfy Mini Series Torrent Download WE LOVE INDONESIA

alice syfy mini series torrent download WE LOVE INDONESIA. Neverland Mini Series on SYFY Torrent : Syfy gamble huge featuring its two-night authentic miniseries occasion Neverland and yes it paid back. The actual best of Part One particular involving Neverland came A couple of.6 000 0000 overall readers from 9-11 p.michael. in Saturday nighttime, upwards Five percent make up the wire network's most recent miniseries Alice (the bring up to date about Alice in Wonderland) via 09. Describes associated with Alice drew A couple of.Three or more trillion viewers. watch Neverland miniseries today, a prequel from Peter Pan and to watch Neverland streaming online and available in torrent links, Megavideo, Sockshare, VideoBB, Videozer, and more. Neverland Mini Series on SYFY. In the advertiser-coveted grown ups 18-49 group, Neverland -- which usually began Syfy's next yearly Countdown to be able to Christmas time - - averaged practically One million audiences. In the elderly 25-54 demo, the two-hour telecast enticed One.Tough luck million readers. The final a part of Neverland broadcast about Syfy about Friday nighttime; ratings to the telecast is going to be accessible overdue Thursday or even earlier Friday. It is just a prequel to T.Mirielle. Barrie's traditional Peter Pan history glaring Rhys Ifans, Keira Knightley, Ould - Friel, Bob Hoskins, Raoul Trujillo and also Charlie Rowe because Chris Skillet. Neverland is manufactured by Dublin-based Similar Films on behalf of MNG Motion pictures, in colaboration with Syfy and also Atmosphere Films Hi-def and is written by RHI Amusement Watch Neverland Mini Series on SYFY Online Free or Download Neverland Mini Series on SYFY. -

Program at Cal State Fullerton (‘11-‘13)

The New American Theatre presents The World Premiere BOXING LESSONS written by JOHN BUNZEL directed by JACK STEHLIN* Produced by JEANNINE WISNOSKY STEHLIN EVE DANZEISEN* STEPHEN TYLER HOWELL ERIC CURTIS JOHNSON* LUKE McCLURE BRUCE NOZICK* SUSAN WILDER* JOHN IACOVELLI JOSEPHINE WANG Scenic Design Lighting Design CHRISTOPHER MOSCATIELLO FLORENCE KEMPER BUNZEL Sound Design Costume Design DAVID SAEWERT LUCY POLLAK Propmaster Publicity VICTORIA HOFFMAN* AVK CREATIVE Casting Graphics DEREK R. COPENHAVER* Production Stage Manager *member of Actors Equity Association THE NEW AMERICAN THEATRE 1312 N. Wilton Pl. Hollywood, CA 90028 [email protected] NewAmericanTheatre.com This performance is supported, in The New American Theatre part, by the Los Angeles County (formerly Circus Theatricals) Board of Supervisors through the Los is a member of the LA Stage Alliance. Angeles County Arts Commission. Facebook.com/NewAmericanTheatre @NewAmericanThtr @NewAmericanTheatre BOXING LESSONS / 1 CAST (in order of appearance) Judy...............................................................................EVE DANZEISEN* Ned....................................................................................LUKE McCLURE Sheriff Bob.......................................................ERIC CURTIS JOHNSON* Meg..................................................................................SUSAN WILDER* Steve...............................................................STEPHEN TYLER HOWELL Billy..................................................................................BRUCE -

Jaime Pressly Cast in New Tv Land Pilot “Jennifer Falls”

JAIME PRESSLY CAST IN NEW TV LAND PILOT “JENNIFER FALLS” New York, NY – August 5, 2013 – Emmy® Award-winning actress Jaime Pressly has been cast in the lead role for TV Land’s new pilot “Jennifer Falls,” it was announced today by Keith Cox, Executive Vice President of Development and Original Programming for the network. Pressly, best known for her work on the NBC series “My Name is Earl,” will play the lead character, Jennifer Doyle, in this multi-camera pilot. “Jennifer Falls" revolves around a career woman and mother (Pressly) who must move back in with her own mom after being let go from her high-powered, six-figure salary job. With her teenage daughter in tow, Jennifer has to face her new life, trying to reconnect with old friends in her hometown and making ends meet as a waitress in her brother’s bar. “It’s amazing to have someone like Jaime Pressly on board for ‘Jennifer Falls,'” said Cox. “We loved this script from the moment we read it, and Jaime just brings the role to life perfectly.” The pilot is written, created and executive produced by Matthew Carlson (“The Wonder Years,” “Malcolm in the Middle”), with Michael Hanel and Mindy Schultheis (“Reba,” “The Exes”) also serving as executive producers. TV Land's current line-up of original sitcoms airs Wednesdays at 10pm ET/PT and includes the hit series "Hot in Cleveland," "The Exes" and "The Soul Man." The series have received several awards and accolades including two 2013 Creative Arts Emmy® nominations: one for "Hot in Cleveland" and the other for "The Exes." All of these series star pop culture icons and fan favorites including Betty White, Valerie Bertinelli, Wendie Malick, Jane Leeves, Kristen Johnston, Donald Faison, Wayne Knight, David Alan Basche, Kelly Stables, Cedric "The Entertainer," Niecy Nash and Wesley Jonathan. -

Biofuturity, Disability, and Crip Communities in Anglophone Speculative Fiction

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Dis-Topic Future: Biofuturity, Disability, and Crip Communities in Anglophone Speculative Fiction A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Amanda Martin Sandino Committee in charge: Professor Shelley Streeby, Chair Professor Michael Davidson Professor Brian Goldfarb Professor Ari Heinrich Professor Sarah Nicolazzo 2018 Copyright Amanda Martin Sandino, 2018 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Amanda Martin Sandino is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ (Chair) University of California, San Diego 2018 iii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my chronic pain support network—nothing about us without us! iv Epigraph “They're looking for this fearsome wizard only to discover that he's nothing but a little tiny fellow. I mean, I don't think the point is that he's tiny. I think the point is, you know, things that we believe we lack are already inside of us just wanting to be found.” – George Crabtree, “Victoria Cross,” Murdoch Mysteries “You don't speak of dreams as unreal. They exist. They leave a mark behind them.” – Ursula K. Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven “Art is not neutral. It either upholds or disrupts the status quo, advancing or regressing justice. We are living now inside the imagination of people who thought economic disparity and environmental destruction were acceptable costs for their power. It is our right and responsibility to write ourselves into the future. All organizing is science fiction. -

Word Search 'Crisis on Infinite Earths'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! December 6 - 12, 2019 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H W Q A R C F E B M R A L Your Key 2 x 3" ad O R F E I G L F I M O E W L E N A B K N F Y R L E T A T N O To Buying S G Y E V I J I M A Y N E T X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad U I H T A N G E L E S G O B E P S Y T O L O N Y W A L F Z A T O B R P E S D A H L E S E R E N S G L Y U S H A N E T B O M X R T E R F H V I K T A F N Z A M O E N N I G L F M Y R I E J Y B L A V P H E L I E T S G F M O Y E V S E Y J C B Z T A R U N R O R E D V I A E A H U V O I L A T T R L O H Z R A A R F Y I M L E A B X I P O M “The L Word: Generation Q” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bette (Porter) (Jennifer) Beals Revival Place your classified ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Shane (McCutcheon) (Katherine) Moennig (Ten Years) Later ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Alice (Pieszecki) (Leisha) Hailey (Los) Angeles 1 x 4" ad (Sarah) Finley (Jacqueline) Toboni Mayoral (Campaign) County Trading Post! brings back past versions of superheroes Deal Merchandise Word Search Micah (Lee) (Leo) Sheng Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item Brandon Routh stars in The CW’s crossover saga priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” which starts Sunday on “Supergirl.” for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Peter Pan Jr - Full Synopsis Peter Pan and the Other Inhabitants of Neverland Open the Show by Introducing the Audience to Their World ("Neverland")

Peter Pan Jr - Full Synopsis Peter Pan and the other inhabitants of Neverland open the show by introducing the audience to their world ("Neverland"). Meanwhile, in the Darling Nursery ("Prologue"), Wendy, Michael, and John are playing before bed as Mrs.Darling and Mr.Darling get ready to go out. Nana, the family dog, and Liza encourage the children to go to bed. Before leaving, Mrs. Darling sings a lullaby with the children to say goodnight ("Tender Shepherd"). As soon as the parents have gone, Peter follows Tinker Bell into the room, searching for Peter’s shadow. Wendy is awakened by the commotion and quickly befriends the mysterious visitor. The Darling children soon set off to Neverland with Peter, travelling the only way possible ("I’m Flying"). Back in Neverland, the Pirates search for the Lost Boys ("Pirate March"). After discovering the Lost Boys’ underground home, Captain Hook and his first mate Smee devise a plan ("Hook’s Tango"), but is chased away by the Crocodile. The Lost Boys remain in peril as the Brave Girls, led by Tiger Lily, arrive on the scene ("Brave Girl Dance"). Peter and the Darlings reach Neverland, frightening the Brave Girls. Finally safe, the Lost Boys celebrate the arrival of their new “mother” ("Wendy"). Captain Hook’s first attempt to poison the Lost Boys is thwarted by their new guardian, and the pirates must devise a new plan ("Hook’s Tarantella"). The next day, the Lost Boys learn a lesson from Peter, their “father” ("I Won’t Grow Up"). When they discover that the pirates have captured Tiger Lily, the Lost Boys help to free her. -

UAB-Psychiatry-Fall-081.Pdf

Fall 2008 Also Inside: Surviving Suicide Loss The Causes and Prevention of Suicide New Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Teaching and Learning Psychotherapy MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Message Jamesfrom H .the Meador-Woodruff, Chairman M.D. elcome to the Fall 2008 issue of UAB Psychia- try. In this issue, we showcase some of our many departmental activities focused on patients of Wevery age, and highlight just a few of the people that sup- port them. Child and adolescent psychiatry is one of our departmental jewels, and is undergoing significant expansion. I am par- ticularly delighted to feature Dr. LaTamia White-Green in this issue, both as a mother of a child with an autism- spectrum disorder (and I thank Teddy and his grandmother both for agreeing to pose for our cover!), but also the new leader of the Civitan-Sparks Clinics. These Clinics are one of UAB’s most important venues for the assessment of children with developmental disorders, training caregivers that serve these patients, and pursuing important research outcome of many psychiatric conditions. One of our junior questions. The Sparks Clinics moved into the Department faculty members, Dr. Monsheel Sodhi, has been funded by of Psychiatry over the past few months, and I am delighted this foundation for her groundbreaking work to find ge- that we have Dr. White-Green to lead our efforts to fur- netic predictors of suicide risk. I am particularly happy to ther strengthen this important group of Clinics. As you introduce Karen Saunders, who shares how her own family will read, we are launching a new capital campaign to raise has been touched by suicide. -

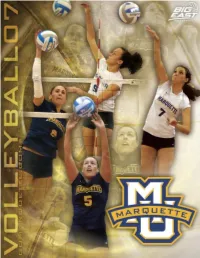

200708 Mu Vb Guide.Pdf

1 Ashlee 2 Leslie 4 Terri 5 Katie OH Fisher OH Bielski L Angst S Weidner 6 Jenn 7 Tiffany 8 Jessica 9 Kimberley 10 Katie MH Brown MH/OH Helmbrecht DS Kieser MH/OH Todd OH Vancura 11 Rabbecka 12 Julie 14 Hailey 15 Caryn OH Gonyo OH Richards DS Viola S Mastandrea Head Coach Assistant Coach Assistant Coach Pati Rolf Erica Heisser Raftyn Birath 20072007 MARQUETTE MARQUETTE VOLLEYBALL VOLLEYBALL TEAM TEAM Back row (L to R): Graydon Larson-Rolf (Manager), Erica Heisser (Assistant Coach), Kent Larson (Volunteer Assistant), Kimberley Todd. Third row: Raftyn Birath (Assistant Coach), Tiffany Helmbrecht, Rabbecka Gonyo, Katie Vancura, Jenn Brown, Peter Thomas (Manager), David Hartman (Manager). Second row: Pati Rolf (Head Coach), Ashlee Fisher, Julie Richards, Terri Angst, Leslie Bielski. Front row: Ellie Rozumalski (Athletic Trainer), Jessica Kieser, Hailey Viola, Katie Weidner, Caryn Mastandrea. L E Y B V O L A L L Table of Contents Table of Contents Quick Facts 2007 Schedule 2 General Information 2007 Roster 3 School . .Marquette University Season Preview 4 Location . .Milwaukee, Wis. Head Coach Pati Rolf 8 Enrollment . .11,000 Nickname . .Golden Eagles Assistant Coach Erica Heisser 11 Colors ...............Blue (PMS 281) and Gold (PMS 123) Assistant Coach Raftyn Birath 12 Home Arena . .Al McGuire Center (4,000) Meet The Team 13 Conference . .BIG EAST 2006 Review 38 President . .Rev. Robert A. Wild, S.J. 2006 Results and Statistics 41 Interim Athletics Dir. .Steve Cottingham Sr.Woman Admin. .Sarah Bobert 2006 Seniors 44 2006 Match by Match 47 Coaching Staff 2006 BIG EAST Recap 56 Season Preview, page 4 Head Coach .