Dermatology Terminology Herbert B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2020 Goal the Goal of the Residency Program Is to Develop Future Leaders in Both Research and Clinical Medicine

Residency Training Program July 2020 Goal The goal of the Residency Program is to develop future leaders in both research and clinical medicine. Flexibility within the program allows for the acquisition of fundamental working knowledge in all subspecialties of dermatology. All residents are taught a scholarly approach to patient care, aimed at integrating clinicopathologic observation with an understanding of the basic pathophysiologic processes of normal and abnormal skin. Penn’s Residency Program consists of conferences, seminars, clinical rotations, research, and an opportunity to participate in the teaching of medical students. An extensive introduction into the department and the William D. James, M.D. Director of Residency Program clinic/patient care service is given to first-year residents. A distinguished clinical faculty and research faculty, coupled with the clinical and laboratory facilities, provides residents with comprehensive training. An appreciation of and participation in the investigative process is an integral part of our residency. Graduates frequently earn clinical or basic science fellowship appointments at universities across the country. Examples of these include: pediatric dermatology, dermatopathology, dermatologic surgery, dermatoepidemiology, postdoctoral and Clinical Educator fellowships. Additional post graduate training has occurred at the NIH and CDC. Graduates of our program populate the faculty at Harvard, Penn, Johns Hopkins, MD Anderson, Dartmouth, Penn State, Washington University, and the Universities of Washington, Pittsburgh, Vermont, South Carolina, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and the University of California San Francisco. Additionally, some enter private practice to become pillars of community medicine. Misha A. Rosenbach, M.D. Associate Director of Residency Program History The first medical school in America, founded in 1765, was named the College of Philadelphia. -

The Use of Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Oral Lesions Due to Pemphigus and Behçet's Disease: a Systematic Review

Davis GE, Sarandev G, Vaughan AT, Al-Eryani K, Enciso R. The Use of Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Oral Lesions due to Pemphigus and Behçet’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J Anesthesiol & Pain Therapy. 2020;1(1):14-23 Systematic Review Open Access The Use of Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Oral Lesions due to Pemphigus and Behçet’s Disease: A Systematic Review Gerald E. Davis II1,2, George Sarandev1, Alexander T. Vaughan1, Kamal Al-Eryani3, Reyes Enciso4* 1Advanced graduate, Master of Science Program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA 2Assistant Dean of Academic Affairs, Assistant Professor, Restorative Dentistry, Meharry Medical College, School of Dentistry, Nashville, Tennessee, USA 3Assistant Professor of Clinical Dentistry, Division of Periodontology, Dental Hygiene & Diagnostic Sciences, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA 4Associate Professor (Instructional), Division of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA Article Info Abstract Article Notes Background: Current treatments for pemphigus and Behçet’s disease, such Received: : March 11, 2019 as corticosteroids, have long-term serious adverse effects. Accepted: : April 29, 2020 Objective: The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the *Correspondence: efficacy of biologic agents (biopharmaceuticals manufactured via a biological *Dr. Reyes Enciso, Associate Professor (Instructional), Division source) on the treatment of intraoral lesions associated with pemphigus and of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow Behçet’s disease compared to glucocorticoids or placebo. School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA; Email: [email protected]. -

Dermatology DDX Deck, 2Nd Edition 65

63. Herpes simplex (cold sores, fever blisters) PREMALIGNANT AND MALIGNANT NON- 64. Varicella (chicken pox) MELANOMA SKIN TUMORS Dermatology DDX Deck, 2nd Edition 65. Herpes zoster (shingles) 126. Basal cell carcinoma 66. Hand, foot, and mouth disease 127. Actinic keratosis TOPICAL THERAPY 128. Squamous cell carcinoma 1. Basic principles of treatment FUNGAL INFECTIONS 129. Bowen disease 2. Topical corticosteroids 67. Candidiasis (moniliasis) 130. Leukoplakia 68. Candidal balanitis 131. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma ECZEMA 69. Candidiasis (diaper dermatitis) 132. Paget disease of the breast 3. Acute eczematous inflammation 70. Candidiasis of large skin folds (candidal 133. Extramammary Paget disease 4. Rhus dermatitis (poison ivy, poison oak, intertrigo) 134. Cutaneous metastasis poison sumac) 71. Tinea versicolor 5. Subacute eczematous inflammation 72. Tinea of the nails NEVI AND MALIGNANT MELANOMA 6. Chronic eczematous inflammation 73. Angular cheilitis 135. Nevi, melanocytic nevi, moles 7. Lichen simplex chronicus 74. Cutaneous fungal infections (tinea) 136. Atypical mole syndrome (dysplastic nevus 8. Hand eczema 75. Tinea of the foot syndrome) 9. Asteatotic eczema 76. Tinea of the groin 137. Malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna 10. Chapped, fissured feet 77. Tinea of the body 138. Melanoma mimics 11. Allergic contact dermatitis 78. Tinea of the hand 139. Congenital melanocytic nevi 12. Irritant contact dermatitis 79. Tinea incognito 13. Fingertip eczema 80. Tinea of the scalp VASCULAR TUMORS AND MALFORMATIONS 14. Keratolysis exfoliativa 81. Tinea of the beard 140. Hemangiomas of infancy 15. Nummular eczema 141. Vascular malformations 16. Pompholyx EXANTHEMS AND DRUG REACTIONS 142. Cherry angioma 17. Prurigo nodularis 82. Non-specific viral rash 143. Angiokeratoma 18. Stasis dermatitis 83. -

General Dermatology Practice Brochure

Appointments Our Providers David A. Cowan, MD, FAAD We are currently accepting • Fellow, American Academy of Dermatology new patients. • Associate, American College of Call today to schedule your appointment Mohs Micrographic Surgery Monday - Friday, 8:00am to 4:30pm Rebecca G. Pomerantz, MD 1-877-661-3376 • Board Certified, American Academy of Cancellations & “No Show” Policy Dermatology If you are unable to keep your scheduled Lisa L. Ellis, MPAS, PA-C appointment, please call the office and we will • Member, American Academy of Physician be more than happy to reschedule for you. Assistants Failure to notify us at least 48 hours prior to your • Member, PA Society of Physician Assistants Medical and appointment may result in a cancellation fee. • Member, Society of Dermatology Physician Prescription Refills Assistants Surgical Refill requests are handled during normal office Sheri L. Rolewski, MSN, CRNP-BC hours when our staff has full access to medical • National Board Certification, Family Nurse Dermatology records. Refills cannot be called in on holidays, Practitioner Specialty weekends or more than twelve months after your • Member, Dermatology Nurse Association last exam. Please have your pharmacy contact our office directly. Test Results SMy Dermatology Appointment You will be notified when we receive your Date/Day _____________________________________ pathology or other test results, usually within two weeks from the date of your procedure. If you Time _________________________________________ do not hear from us within three -

Dermatology at the Berkeley Outpatient Center

Dermatology Berkeley Outpatient Center Overview Encompassing both medical and cosmetic dermatology, our experts at the Berkeley Outpatient Center offer a full range of diagnostic, treatment and surgical services for patients with cutaneous conditions. Surgical Dermatology • Fellowship-trained expertise in • Close coordination with Plastic Surgery Mohs micrographic surgery for at the Berkeley Outpatient Center, treatment of skin cancers including allowing for streamlined treatment for basal cell carcinomas and squamous related procedures in one location cell carcinomas, as well as treatment of • Outpatient surgery for removal of melanoma in situ with MART-1 staining benign skin growths and skin cancers Medical Dermatology - Conditions Treated/Services Offered • Acne, rosacea and related conditions • Mole/Atypical nevus/Melanoma • Sun-damaged skin surveillance • Aesthetic/Cosmetic dermatology • Non-melanoma skin cancers • Eczema and atopic dermatitis • Pigmentation disorders • HIV/AIDS-related skin conditions • Psoriasis • Lumps under the skin • Rashes • Infections of the skin (bacterial, viral, • Skin checks for patients with fungal and other) concerning lesions • Melanoma • Warts When to see a Dermatologist For more information, please call Dermatology Services at (510) 985-5200. Dermatology Services Providing integrated care in the community. Our Dermatology Team Erin Amerson, MD Drew Saylor, MD, MPH UCSF Health UCSF Health Dermatologist Dermatologic surgeon To learn more about our doctors, visit ucsfhealth.org/find_a_doctor. Office location: Berkeley Outpatient Center 3100 San Pablo Avenue Berkeley, CA 94702 (510) 985-5200 To learn more about our Berkeley Outpatient Center, Adeline St visit johnmuirhealth.com/ September 2020 berkeleyopc.. -

Genital Dermatology

GENITAL DERMATOLOGY BARRY D. GOLDMAN, M.D. 150 Broadway, Suite 1110 NEW YORK, NY 10038 E-MAIL [email protected] INTRODUCTION Genital dermatology encompasses a wide variety of lesions and skin rashes that affect the genital area. Some are found only on the genitals while other usually occur elsewhere and may take on an atypical appearance on the genitals. The genitals are covered by thin skin that is usually moist, hence the dry scaliness associated with skin rashes on other parts of the body may not be present. In addition, genital skin may be more sensitive to cleansers and medications than elsewhere, emphasizing the necessity of taking a good history. The physical examination often requires a thorough skin evaluation to determine the presence or lack of similar lesions on the body which may aid diagnosis. Discussion of genital dermatology can be divided according to morphology or location. This article divides disease entities according to etiology. The clinician must determine whether a genital eruption is related to a sexually transmitted disease, a dermatoses limited to the genitals, or part of a widespread eruption. SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS AFFECTING THE GENITAL SKIN Genital warts (condyloma) have become widespread. The human papillomavirus (HPV) which causes genital warts can be found on the genitals in at least 10-15% of the population. One study of college students found a prevalence of 44% using polymerase chain reactions on cervical lavages at some point during their enrollment. Most of these infection spontaneously resolved. Only a minority of patients with HPV develop genital warts. Most genital warts are associated with low risk HPV types 6 and 11 which rarely cause cervical cancer. -

Short Anagen Syndrome: a Case Study

Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications, 2012, 2, 14-15 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jcdsa.2012.21004 Published Online March 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jcdsa) Short Anagen Syndrome: A Case Study Martina Alés Fernández, Francisco M. Camacho Martínez Department of Dermatology, Virgen Macarena University Hospital, Seville, Spain. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Received October 31st, 2011; revised November 18th, 2011; revised November 29th, 2011 ABSTRACT Short anagen syndrome is a relatively recently described entity. This syndrome is an unusual condition where the ana- gen growth phase of hair follicles is shorter than normal. Its clinical characteristics and trichogram findings contribute to the diagnosis of this trichosis. Keywords: Anagen Syndrome 1. Case Report Three-years-old girl with low density and slow growth scalp hair that had not been cut since birth. Her birth and medical history were unremarkable. The physical ex- amination revealed short and fine brown scalp hair with decreased density in frontoparietal areas (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal, without any abnormalities in eyelashes, eyebrows, teeth, nails or skin. The hair pull test was negative. The trichogram demon- strated some dystrophic hairs, but the most important data was an increased number of telogen hairs with a consistent decreased number of anagen hairs (Figure 2). The anagen to telogen ratio (7:28) was significantly re- duced with only 25% of hairs in anagen. 2. Discussion Short anagen syndrome is a relatively recently recog- nized entity poorly documented. Short hair due to a short anagen phase was described in 1987 by Kersey as part of tricho-dental syndrome [1]. -

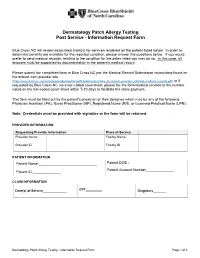

Dermatology Patch Allergy Testing Post Service - Information Request Form

Dermatology Patch Allergy Testing Post Service - Information Request Form Blue Cross NC will review associated claim(s) for services rendered on the patient listed below. In order to determine benefits are available for the reported condition, please answer the questions below. If you would prefer to send medical records, relating to the condition for the dates listed you may do so. In this case, all answers must be supported by documentation in the patient's medical record. Please submit the completed form to Blue Cross NC per the Medical Record Submission instructions found on the bcbsnc.com provider site (https://www.bcbsnc.com/assets/providers/public/pdfs/submissions/how_to_submit_provider_initiated_medical_records.pdf) or if requested by Blue Cross NC via a bar-coded coversheet, please fax the form/medical records to the number noted on the bar-coded cover sheet within 7-10 days to facilitate the claim payment. This form must be filled out by the patient's physician or their designee which may be any of the following: Physician Assistant (PA), Nurse Practitioner (NP), Registered Nurse (RN), or Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN). Note: Credentials must be provided with signature or the form will be returned. PROVIDER INFORMATION Requesting Provider Information Place of Service Provider Name Facility Name Provider ID Facility ID PATIENT INFORMATION Patient Name:_____________________________ Patient DOB :_____________ Patient Account Number______________ Patient ID:______________ CLAIM INFORMATION Date(s) of Service_____________ CPT_________ Diagnosis_______ Dermatology Patch Allergy Testing - Information Request Form Page 1 of 3 CLINICAL INFORMATION Did the patient have direct skin testing (for immediate hypersensitivity) by: Percutaneous or epicutaneous (scratch, prick, or puncture)? ________________ Intradermal testing? ___________________________________ Inhalant allergy evaluation? _________________ Did the patient have patch (application) testing (most commonly used: T.R.U.E. -

Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions

Dermatology for the Non-Dermatologist May 30 – June 3, 2018 - 1 - Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions History remains ESSENTIAL to establish diagnosis – duration, treatments, prior history of skin conditions, drug use, systemic illness, etc., etc. Historical characteristics of lesions and rashes are also key elements of the description. Painful vs. painless? Pruritic? Burning sensation? Key descriptive elements – 1- definition and morphology of the lesion, 2- location and the extent of the disease. DEFINITIONS: Atrophy: Thinning of the epidermis and/or dermis causing a shiny appearance or fine wrinkling and/or depression of the skin (common causes: steroids, sudden weight gain, “stretch marks”) Bulla: Circumscribed superficial collection of fluid below or within the epidermis > 5mm (if <5mm vesicle), may be formed by the coalescence of vesicles (blister) Burrow: A linear, “threadlike” elevation of the skin, typically a few millimeters long. (scabies) Comedo: A plugged sebaceous follicle, such as closed (whitehead) & open comedones (blackhead) in acne Crust: Dried residue of serum, blood or pus (scab) Cyst: A circumscribed, usually slightly compressible, round, walled lesion, below the epidermis, may be filled with fluid or semi-solid material (sebaceous cyst, cystic acne) Dermatitis: nonspecific term for inflammation of the skin (many possible causes); may be a specific condition, e.g. atopic dermatitis Eczema: a generic term for acute or chronic inflammatory conditions of the skin. Typically appears erythematous, -

Hair Loss in Infancy

SCIENCE CITATIONINDEXINDEXED MEDICUS INDEX BY (MEDLINE) EXPANDED (ISI) OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI DERMATOLOGIA MEDICA, CHIRURGICA, ESTETICA E DELLE MALATTIE SESSUALMENTE TRASMESSE (SIDeMaST) VOLUME 149 - No. 1 - FEBRUARY 2014 Anno: 2014 Lavoro: 4731-MD Mese: Febraury titolo breve: Hair loss in infancy Volume: 149 primo autore: MORENO-ROMERO No: 1 pagine: 55-78 Rivista: GIORNALE ITALIANO DI DERMATOLOGIA E VENEREOLOGIA Cod Rivista: G ITAL DERMATOL VENEREOL G ITAL DERMATOL VENEREOL 2014;149:55-78 Hair loss in infancy J. A. MORENO-ROMERO 1, R. GRIMALT 2 Hair diseases represent a signifcant portion of cases seen 1Department of Dermatology by pediatric dermatologists although hair has always been Hospital General de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain a secondary aspect in pediatricians and dermatologists 2Universitat de Barcelona training, on the erroneous basis that there is not much in- Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain formation extractable from it. Dermatologists are in the enviable situation of being able to study many disorders with simple diagnostic techniques. The hair is easily ac- cessible to examination but, paradoxically, this approach is often disregarded by non-dermatologist. This paper has Embryology and normal hair development been written on the purpose of trying to serve in the diag- nostic process of daily practice, and trying to help, for ex- ample, to distinguish between certain acquired and some The full complement of hair follicles is present genetically determined hair diseases. We will focus on all at birth and no new hair follicles develop thereafter. the data that can be obtained from our patients’ hair and Each follicle is capable of producing three different try to help on using the messages given by hair for each types of hair: lanugo, vellus and terminal. -

Research Article Mucocutaneous Manifestations of HIV and the Correlation with WHO Clinical Staging in a Tertiary Hospital in Nigeria

Hindawi Publishing Corporation AIDS Research and Treatment Volume 2014, Article ID 360970, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/360970 Research Article Mucocutaneous Manifestations of HIV and the Correlation with WHO Clinical Staging in a Tertiary Hospital in Nigeria Olumayowa Abimbola Oninla Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, P.O. Box 2545, Ile-Ife 250005, Osun State, Nigeria Correspondence should be addressed to Olumayowa Abimbola Oninla; [email protected] Received 31 July 2014; Revised 15 November 2014; Accepted 25 November 2014; Published 21 December 2014 Academic Editor: P. K. Nicholas Copyright © 2014 Olumayowa Abimbola Oninla. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Skin diseases are indicators of HIV/AIDS which correlates with WHO clinical stages. In resource limited environment where CD4 count is not readily available, they can be used in assessing HIV patients. The study aims to determine the mucocutaneous manifestations in HIV positive patients and their correlation with WHO clinical stages. A prospective cross-sectional study of mucocutaneous conditions was done among 215 newly diagnosed HIV patients from June 2008 to May 2012 at adult ART clinic, Wesley Guild Hospital Unit, OAU Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ilesha, Osun State, Nigeria. There were 156 dermatoses with oral/oesophageal/vaginal candidiasis (41.1%), PPE (24.4%), dermatophytic infections (8.9%), and herpes zoster (3.8%) as the most common dermatoses. The proportions of dermatoses were 4.5%, 21.8%, 53.2%, and 20.5% in stages 1–4, respectively. -

Dermatologic Nuances in Children with Skin of Color

5/21/2019 Dermatologic Nuances in Children with Skin of Color Candrice R. Heath, MD, FAAP, FAAD Director, Pediatric Dermatology LKSOM Temple University @DrCandriceHeath Advisory Board – Pfizer, Regeneron-Sanofi Consultant –Marketing – Unilever, Proctor & Gamble Speaker’s Bureau - Pfizer I do not intend to discuss on-FDA approved or investigational use of products in my presentation. • Recognize common hair, scalp and skin disorders that may present differently in children with skin of color • Select appropriate treatment options based upon common cultural preferences to increase adherence • Establish treatment algorithm for challenging cases 1 5/21/2019 • 2050 : Over half of the United States population will be people of color • 2050 : 1 in 3 US residents will be Hispanic • 2023 : Over half of the children in the US will be people of color • Focuses on ethnic and racial groups who have – similar skin characteristics – similar skin diseases – similar reaction patterns to those skin diseases Taylor SC et al. (2016) Defining Skin of Color. In Taylor & Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2016 Type I always burns, never tans (palest) Type II usually burns, tans minimally Type III sometimes mild burn, tans uniformly Type IV burns minimally, always tans well (moderate brown) Type V very rarely burns, tans very easily (dark brown) Type VI Never burns (deeply pigmented dark brown to darkest brown) 2 5/21/2019 • Black • Asian • Hispanic • Other Not so fast… • Darker skin hues • The term “race” is faulty – Race may not equal biological or genetic inheritance – There is not one gene or characteristic that separates every person of one race from another Taylor SC et al.