What to Consider When Writing Covered Calls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Department of Mathematics

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Department of Mathematics ASRM 410 Investments and Financial Markets Fall 2018 Chapter 5 Option Greeks and Risk Management by Alfred Chong Learning Objectives: 5.1 Option Greeks: Black-Scholes valuation formula at time t, observed values, model inputs, option characteristics, option Greeks, partial derivatives, sensitivity, change infinitesimally, Delta, Gamma, theta, Vega, rho, Psi, option Greek of portfolio, absolute change, option elasticity, percentage change, option elasticity of portfolio. 5.2 Applications of Option Greeks: risk management via hedging, immunization, adverse market changes, delta-neutrality, delta-hedging, local, re-balance, from- time-to-time, holding profit, delta-hedging, first order, prudent, delta-gamma- hedging, gamma-neutrality, option value approximation, observed values change inevitably, Taylor series expansion, second order approximation, delta-gamma- theta approximation, delta approximation, delta-gamma approximation. Further Exercises: SOA Advanced Derivatives Samples Question 9. 1 5.1 Option Greeks 5.1.1 Consider a continuous-time setting t ≥ 0. Assume that the Black-Scholes framework holds as in 4.2.2{4.2.4. 5.1.2 The time-0 Black-Scholes European call and put option valuation formula in 4.2.9 and 4.2.10 can be generalized to those at time t: −δ(T −t) −r(T −t) C (t; S; δ; r; σ; K; T ) = Se N (d1) − Ke N (d2) P = Ft;T N (d1) − PVt;T (K) N (d2); −r(T −t) −δ(T −t) P (t; S; δ; r; σ; K; T ) = Ke N (−d2) − Se N (−d1) P = PVt;T (K) N (−d2) − Ft;T N (−d1) ; where d1 and d2 are given by S 1 2 ln K + r − δ + 2 σ (T − t) d1 = p ; σ T − t S 1 2 p ln K + r − δ − 2 σ (T − t) d2 = p = d1 − σ T − t: σ T − t 5.1.3 The option value V is a function of observed values, t and S, model inputs, δ, r, and σ, as well as option characteristics, K and T . -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Yuichi Katsura

P&TcrvvCJ Efficient ValtmVmm-and Hedging of Structured Credit Products Yuichi Katsura A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London May 2005 Centre for Quantitative Finance Imperial College London nit~ýl. ABSTRACT Structured credit derivatives such as synthetic collateralized debt obligations (CDO) have been the principal growth engine in the fixed income market over the last few years. Val- uation and risk management of structured credit products by meads of Monte Carlo sim- ulations tend to suffer from numerical instability and heavy computational time. After a brief description of single name credit derivatives that underlie structured credit deriva- tives, the factor model is introduced as the portfolio credit derivatives pricing tool. This thesis then describes the rapid pricing and hedging of portfolio credit derivatives using the analytical approximation model and semi-analytical models under several specifications of factor models. When a full correlation structure is assumed or the pricing of exotic structure credit products with non-linear pay-offs is involved, the semi-analytical tractability is lost and we have to resort to the time-consuming Monte Carlo method. As a Monte Carlo variance reduction technique we extend the importance sampling method introduced to credit risk modelling by Joshi [2004] to the general n-factor problem. The large homogeneouspool model is also applied to the method of control variates as a new variance reduction tech- niques for pricing structured credit products. The combination of both methods is examined and it turns out to be the optimal choice. We also show how sensitivities of a CDO tranche can be computed efficiently by semi-analytical and Monte Carlo framework. -

RT Options Scanner Guide

RT Options Scanner Introduction Our RT Options Scanner allows you to search in real-time through all publicly traded US equities and indexes options (more than 170,000 options contracts total) for trading opportunities involving strategies like: - Naked or Covered Write Protective Purchase, etc. - Any complex multi-leg option strategy – to find the “missing leg” - Calendar Spreads Search is performed against our Options Database that is updated in real-time and driven by HyperFeed’s Ticker-Plant and our Implied Volatility Calculation Engine. We offer both 20-minute delayed and real-time modes. Unlike other search engines using real-time quotes data only our system takes advantage of individual contracts Implied Volatilities calculated in real-time using our high-performance Volatility Engine. The Scanner is universal, that is, it is not confined to any special type of option strategy. Rather, it allows determining the option you need in the following terms: – Cost – Moneyness – Expiry – Liquidity – Risk The Scanner offers Basic and Advanced Search Interfaces. Basic interface can be used to find options contracts satisfying, for example, such requirements: “I need expensive Calls for Covered Call Write Strategy. They should expire soon and be slightly out of the money. Do not care much as far as liquidity, but do not like to bear high risk.” This can be done in five seconds - set the search filters to: Cost -> Dear Moneyness -> OTM Expiry -> Short term Liquidity -> Any Risk -> Moderate and press the “Search” button. It is that easy. In fact, if your request is exactly as above, you can just press the “Search” button - these values are the default filtering criteria. -

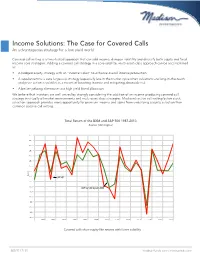

Income Solutions: the Case for Covered Calls an Advantageous Strategy for a Low-Yield World

Income Solutions: The Case for Covered Calls An advantageous strategy for a low-yield world Covered call writing is a time-tested approach that can add income, dampen volatility and diversify both equity and fixed income core strategies. Adding a covered call strategy in a core-satellite, multi-asset-class approach can be accomplished as: • A hedged equity strategy with an “income kicker” to enhance overall income production • A supplement to a core large-cap strategy (especially late in the market cycle when valuations are long-in-the-tooth and price action is volatile) as a means of boosting income and mitigating downside risk • A better-yielding alternative to a high yield bond allocation We believe that investors are well-served by strongly considering the addition of an income-producing covered call strategy in virtually all market environments and multi-asset class strategies. Madison’s active call writing/active stock selection approach provides more opportunity for premium income and alpha from underlying security selection than common passive call writing. Total Return of the BXM and S&P 500 1987-2013 Rolling Returns Source: Morningstar Time Period: 1/1/1987 to 12/31/2013 Rolling Window: 1 Year 1 Year shift 40.0 35.0 30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 Return 0.0 S&P 500 -5.0 -10.0 CBOE S&P 500 Buywrite BXM -15.0 -20.0 -25.0 -30.0 -35.0 -40.0 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 S&P 500 TR USD Covered calls show equity-likeCBOE returns S&P 500 with Buyw ritelower BXM volatility Source: Morningstar Direct 888.971.7135 madisonfunds.com | madisonadv.com Covered Call Strategy(A) Benefits of Individual Stock Options vs. -

Structured Products in Asia

2015 ISSUE: NOVEMBER Structured Products in Asia hubbis.com 1st Leonteq has received more than 20 awards since its foundation in 2007 THE QUINTESSENCE OF OUR MISSION STATEMENT LET´S REDEFINE YOUR INVESTMENT EXPERIENCE Leonteq’s explicit goal is to make a difference through particular transparency in structured investment products and to be the preferred technology and service partner for investment solutions. We count on experienced industry experts with a focus on achieving client’s goals and a fi rst class IT infrastructure, setting new stand- ards in stability and fl exibility. OUR DIFFERENTIATION Modern platform • Integrated IT platform built from ground up with a focus on automation of key processes in the value chain • Platform functionality to address increased customer demand for transparency, service, liquidity, security and sustainability Vertical integration • Control of the entire value chain as a basis for proactive service tailored to specifi c needs of clients • Automation of key processes mitigating operational risks Competitive cost per issued product • Modern platform resulting in a competitive cost per issued product allowing for small ticket sizes LEGAL DISCLAIMER Leonteq Securities (Hong Kong) Limited (CE no.AVV960) (“Leonteq Hong Kong”) is responsible for the distribution of this publication in Hong Kong. It is licensed and regulated by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission for Types 1 and 4 regulated activities. The services and products it provides are available only to “profes- sional investors” as defi ned in the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) of Hong Kong. This document is being communicated to you solely for the purposes of providing information regarding the products and services that the Leonteq group currently offers, subject to applicable laws and regulations. -

Option Greeks Demystified

Webinar Presentation Option Greeks Demystified Presented by Trading Strategy Desk 1 Fidelity Brokerage Services, Member NYSE, SIPC, 900 Salem Street, Smithfield, RI 02917. © 2016 FMR LLC. All rights reserved. 764207.1.0 Disclosures Options trading entails significant risk and is not appropriate for all investors. Certain complex options strategies carry additional risk. Before trading options, please read Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, and call 800-544- 5115 to be approved for options trading. Supporting documentation for any claims, if applicable, will be furnished upon request. Examples in this presentation do not include transaction costs (commissions, margin interest, fees) or tax implications, but they should be considered prior to entering into any transactions. The information in this presentation, including examples using actual securities and price data, is strictly for illustrative and educational purposes only and is not to be construed as an endorsement, recommendation. Active Trader Pro PlatformsSM is available to customers trading 36 times or more in a rolling 12-month period; customers who trade 120 times or more have access to Recognia anticipated events and Elliott Wave analysis. Greeks are mathematical calculations used to determine the effect of various factors on options. Goal of this webinar Demystify what Options Greeks are and explain how they are used in plain English. What we will cover: What the Greeks are What the Greeks tell us How the Greeks can help with planning option trades How the Greeks can help with managing option trades The Greeks What the Greeks are: • Delta • Gamma • Vega • Theta • Rho But what do they mean? Greeks What do they tell me? In simplest terms, Greeks give traders a theoretical way to judge their exposure to various options pricing inputs. -

White Paper Volatility: Instruments and Strategies

White Paper Volatility: Instruments and Strategies Clemens H. Glaffig Panathea Capital Partners GmbH & Co. KG, Freiburg, Germany July 30, 2019 This paper is for informational purposes only and is not intended to constitute an offer, advice, or recommendation in any way. Panathea assumes no responsibility for the content or completeness of the information contained in this document. Table of Contents 0. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Ihe VIX Index .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 General Comments and Performance ......................................................................................... 2 What Does it mean to have a VIX of 20% .......................................................................... 2 A nerdy side note ................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 The Calculation of the VIX Index ............................................................................................. 4 1.3 Mathematical formalism: How to derive the VIX valuation formula ...................................... 5 1.4 VIX Futures .............................................................................................................................. 6 The Pricing of VIX Futures ................................................................................................ -

Straddles and Strangles to Help Manage Stock Events

Webinar Presentation Using Straddles and Strangles to Help Manage Stock Events Presented by Trading Strategy Desk 1 Fidelity Brokerage Services LLC ("FBS"), Member NYSE, SIPC, 900 Salem Street, Smithfield, RI 02917 690099.3.0 Disclosures Options’ trading entails significant risk and is not appropriate for all investors. Certain complex options strategies carry additional risk. Before trading options, please read Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options, and call 800-544- 5115 to be approved for options trading. Supporting documentation for any claims, if applicable, will be furnished upon request. Examples in this presentation do not include transaction costs (commissions, margin interest, fees) or tax implications, but they should be considered prior to entering into any transactions. The information in this presentation, including examples using actual securities and price data, is strictly for illustrative and educational purposes only and is not to be construed as an endorsement, or recommendation. 2 Disclosures (cont.) Greeks are mathematical calculations used to determine the effect of various factors on options. Active Trader Pro PlatformsSM is available to customers trading 36 times or more in a rolling 12-month period; customers who trade 120 times or more have access to Recognia anticipated events and Elliott Wave analysis. Technical analysis focuses on market action — specifically, volume and price. Technical analysis is only one approach to analyzing stocks. When considering which stocks to buy or sell, you should use the approach that you're most comfortable with. As with all your investments, you must make your own determination as to whether an investment in any particular security or securities is right for you based on your investment objectives, risk tolerance, and financial situation. -

FINANCIAL RISK the GREEKS the Whole of This Presentation Is As A

FINANCIAL RISK THE GREEKS The whole of this presentation is as a result of the collective efforts of both participants. MICHAEL AGYAPONG BOATENG Email: [email protected] MAVIS ASSIBEY-YEBOAH Email: [email protected] DECEMBER 1, 2011 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. THE BLACK-SCHOLES MODEL 3 3. THE GREEKS 4 4. HIGHER-ORDER GREEKS 7 5. CONCLUSION 8 6. STUDY GUIDE 8 7. REFERENCES 8 2 1. INTRODUCTION The price of a single option or a position involving multiple options as the market changes is very difficult to predict. This results from the fact that price does not always move in correspondence with the price of the underlying asset. As such, it is of major interest to understand factors that contribute to the movement in price of an option, and what effect they have. Most option traders therefore turn to the Greeks which provide a means in measuring the sensitivity of an option price by quantifying the factors. The Greeks are so named because they are often denoted by Greek letters. The Greeks, as vital tools in risk management measures sensitivity of the value of the portfolio relative to a small change in a given underlying parameter. This treats accompanying risks in isolation to rebalance the portfolio accordingly so as to achieve a desirable exposure. In this project, the derivation and analysis of the Greeks will be based on the Black-Scholes model. This is because, they are easy to calculate, and are very useful for derivatives traders, especially those who seek to hedge their portfolios from adverse changes in market conditions. -

Greece's Sovereign Debt and Economic Realism

abcd POLICY INSIGHT No.90 June 2017 Greece’s sovereign debt and economic realism Jeremy Bulow and John Geanakoplos Stanford Business School; Yale University Introduction still-unspecified debt relief measures that would The problem make the remaining debt repayable. Meanwhile, unrest and labour strife remain high in Greece, and reek unemployment currently stands at potential foreign investors are still scared off by the 23% (Hellencic Statistical Authority 2016), uncertainty surrounding the debt. The creditors Gand has exceeded 20% for five years. have yet to receive any net payments, and all the Greek GDP is down 25% from its peak in 2009, ministers of Europe are obliged to attend to the and infrastructure investment has been almost Greek debt problem, instead of to more pressing nonexistent over the ensuing seven years. Young issues like terrorism, Brexit, Putin, Trump, and the people have been emigrating in droves, exacerbating refugee crisis. More troubling, this is just a replay what was already one of the most alarming old/ of the same exhausting scenario we have seen young ratios in the world. Capital flight has cost repeated time and again. the banks roughly half their deposits, while half their loans are non-performing. The sovereign We present our analysis of how sophisticated and debt/GDP is almost 180%; worse, the debt is owed experienced negotiators like the IMF, the Eurozone almost entirely to foreigners, and GDP is stated leadership, and by now even the Greeks, could have in what, for Greece, is an over-valued currency.1 let negotiations drag out for so many years. -

Value at Risk for Linear and Non-Linear Derivatives

Value at Risk for Linear and Non-Linear Derivatives by Clemens U. Frei (Under the direction of John T. Scruggs) Abstract This paper examines the question whether standard parametric Value at Risk approaches, such as the delta-normal and the delta-gamma approach and their assumptions are appropriate for derivative positions such as forward and option contracts. The delta-normal and delta-gamma approaches are both methods based on a first-order or on a second-order Taylor series expansion. We will see that the delta-normal method is reliable for linear derivatives although it can lead to signif- icant approximation errors in the case of non-linearity. The delta-gamma method provides a better approximation because this method includes second order-effects. The main problem with delta-gamma methods is the estimation of the quantile of the profit and loss distribution. Empiric results by other authors suggest the use of a Cornish-Fisher expansion. The delta-gamma method when using a Cornish-Fisher expansion provides an approximation which is close to the results calculated by Monte Carlo Simulation methods but is computationally more efficient. Index words: Value at Risk, Variance-Covariance approach, Delta-Normal approach, Delta-Gamma approach, Market Risk, Derivatives, Taylor series expansion. Value at Risk for Linear and Non-Linear Derivatives by Clemens U. Frei Vordiplom, University of Bielefeld, Germany, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Athens, Georgia 2003 °c 2003 Clemens U. Frei All Rights Reserved Value at Risk for Linear and Non-Linear Derivatives by Clemens U.