Looking for the Vinaya: Monastic Discipline in the Practical Canons of the Theravada 281

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Withdrawal from the Monastic Community and Re-Ordination of Former Monastics in the Dharmaguptaka Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography WITHDRAWAL FROM THE MONASTIC COMMUNITY AND RE-ORDINATION OF FORMER MONASTICS IN THE DHARMAGUPTAKA TRADITION ANN HEIRMAN Centre for Buddhist Studies, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Ghent University, [email protected] Abstract: At the apex of Buddhist monasticism are its fully ordained members—Buddhist monks (bhikṣu) and nuns (bhikṣuṇī). The texts on monastic discipline (vinayas) indicate that some monks and nuns, at certain points in their lives, may choose to withdraw from the saṃgha (monastic community). The vinaya texts from every tradition attempt to regulate such decisions, as well as the re-ordination of former monastics. In this paper, I focus on the Dharmaguptaka tradition, the vinaya of which has become standard in China and neighboring regions. My intention is to answer intriguing questions raised by Petra Kieffer-Pülz in her study on the re-ordination of nuns in the Theravāda tradition, which appeared in the first volume of this journal (2015–2016): which options are available to monks and nuns who wish to withdraw from the monastic community; and is it possible for them to gain readmission to the saṃgha? I also address a third question: what does this imply for the Dharmaguptaka tradition? My research focuses on the Dharmaguptaka vinaya, and on the commentaries of the most prominent Chinese vinaya master, Daoxuan (596–667 CE), whose work lies at the heart of standard—and contemporary—under- standing of vinayas in China. Keywords: formal and informal withdrawal; re-ordination; Buddhist monks; Buddhist nuns; Dharmaguptaka 159 160 BUDDHISM, LAW & SOCIETY [Vol. -

Remarks About the History of the Sarvāstivāda Buddhism

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXVII, Z. 1, 2014, (s. 255–268) CHARLES WILLEMEN Remarks about the History of the Sarvāstivāda Buddhism Abstract Study about the history of a specific Buddhist monastic lineage known as “Sarvāstivāda” based on an overview of the history of its literature. Keywords: Sarvāstivāda, Buddhism, schism, Mahāyāna, Abhidharma, India, Gandhāra All scholars agree that the Sarvāstivāda (“Proclaiming that Everything Exists”) Buddhism was strong in India’s north-western cultural area. All agree that there was the first and seminal schism between the Sthaviravāda and the Mahāsāṅghika. However, many questions still remain to be answered. For instance, when did the first schism take place? Where exactly in India’s north-western area? We know what the Theravāda tradition has to say, but this is the voice of just one Buddhist tradition. Jibin 罽賓 The Chinese term Jibin is used to designate the north-western cultural area of India. For many years it has been maintained by Buddhist scholars that it is a phonetic rendering of a Prakrit word for Kaśmīra. In 2009 Seishi Karashima wrote that Jibin is a Chinese phonetic rendering of Kaśpīr, a Gāndhārī form of Kaśmīra.1 In 1993 Fumio Enomoto postulated that Jibin is a phonetic rendering of Kapiśa (Kāpiśī, Bagram).2 Historians have long held a different view. In his article of 1996 János Harmatta said that in the seventh century Jibin denoted the Kapiśa-Gandhāra area.3 For this opinion he relied on 1 Karashima 2009: 56–57. 2 Enomoto 1993: 265–266. 3 Harmatta (1996) 1999: 371, 373–379. 256 CHARLES WILLEMEN Édouard Chavannes’s work published in 1903. -

Mahayana Buddhism: the Doctrinal Foundations, Second Edition

9780203428474_4_001.qxd 16/6/08 11:55 AM Page 1 1 Introduction Buddhism: doctrinal diversity and (relative) moral unity There is a Tibetan saying that just as every valley has its own language so every teacher has his own doctrine. This is an exaggeration on both counts, but it does indicate the diversity to be found within Buddhism and the important role of a teacher in mediating a received tradition and adapting it to the needs, the personal transformation, of the pupil. This divers- ity prevents, or strongly hinders, generalization about Buddhism as a whole. Nevertheless it is a diversity which Mahayana Buddhists have rather gloried in, seen not as a scandal but as something to be proud of, indicating a richness and multifaceted ability to aid the spiritual quest of all sentient, and not just human, beings. It is important to emphasize this lack of unanimity at the outset. We are dealing with a religion with some 2,500 years of doctrinal development in an environment where scho- lastic precision and subtlety was at a premium. There are no Buddhist popes, no creeds, and, although there were councils in the early years, no attempts to impose uniformity of doctrine over the entire monastic, let alone lay, establishment. Buddhism spread widely across Central, South, South-East, and East Asia. It played an important role in aiding the cultural and spiritual development of nomads and tribesmen, but it also encountered peoples already very culturally and spiritually developed, most notably those of China, where it interacted with the indigenous civilization, modifying its doctrine and behaviour in the process. -

Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1St Century B.C. to 6Th Century A.D.)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. ISSN 2250-3226 Volume 7, Number 2 (2017), pp. 149-152 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1st Century B.C. to 6th Century A.D.) Vaishali Bhagwatkar Barkatullah Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal (M.P.) India Abstract Buddhism is a world religion, which arose in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama who was deemed a "Buddha" ("Awakened One"). Buddhism spread outside of Magadha starting in the Buddha's lifetime. With the reign of the Buddhist Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist community split into two branches: the Mahasaṃghika and the Sthaviravada, each of which spread throughout India and split into numerous sub-sects. In modern times, two major branches of Buddhism exist: the Theravada in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and the Mahayana throughout the Himalayas and East Asia. INTRODUCTION Buddhism remains the primary or a major religion in the Himalayan areas such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, the Darjeeling hills in West Bengal, and the Lahaul and Spiti areas of upper Himachal Pradesh. Remains have also been found in Andhra Pradesh, the origin of Mahayana Buddhism. Buddhism has been reemerging in India since the past century, due to its adoption by many Indian intellectuals, the migration of Buddhist Tibetan exiles, and the mass conversion of hundreds of thousands of Hindu Dalits. According to the 2001 census, Buddhists make up 0.8% of India's population, or 7.95 million individuals. Buddha was born in Lumbini, in Nepal, to a Kapilvastu King of the Shakya Kingdom named Suddhodana. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-Of-Age Motion Picture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture Matthew J. Tesoro The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1447 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 MATTHEW TESORO All Rights Reserved ii Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ____________ ________________________ Date Robert Singer Thesis Advisor ____________ ________________________ Date Matthew Gold MALS Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of- Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro Advisor: Robert Singer This thesis will identify how the principle male character in select film narratives transforms from childhood through his adolescence in multiple locations and historical eras. -

The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 27 Number 1 2004 David SEYFORT RUEGG Aspects of the Investigation of the (earlier) Indian Mahayana....... 3 Giulio AGOSTINI Buddhist Sources on Feticide as Distinct from Homicide ............... 63 Alexander WYNNE The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature ................ 97 Robert MAYER Pelliot tibétain 349: A Dunhuang Tibetan Text on rDo rje Phur pa 129 Sam VAN SCHAIK The Early Days of the Great Perfection........................................... 165 Charles MÜLLER The Yogacara Two Hindrances and their Reinterpretations in East Asia.................................................................................................... 207 Book Review Kurt A. BEHRENDT, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara. Handbuch der Orientalistik, section II, India, volume seventeen, Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2004 by Gérard FUSSMAN............................................................................. 237 Notes on the Contributors............................................................................ 251 THE ORAL TRANSMISSION OF EARLY BUDDHIST LITERATURE1 ALEXANDER WYNNE Two theories have been proposed to explain the oral transmission of early Buddhist literature. Some scholars have argued that the early literature was not rigidly fixed because it was improvised in recitation, whereas others have claimed that word for word accuracy was required when it was recited. This paper examines these different theories and shows that the internal evi- dence of the Pali canon supports the theory of a relatively fixed oral trans- mission of the early Buddhist literature. 1. Introduction Our knowledge of early Buddhism depends entirely upon the canoni- cal texts which claim to go back to the Buddha’s life and soon afterwards. But these texts, contained primarily in the Sutra and Vinaya collections of the various sects, are of questionable historical worth, for their most basic claim cannot be entirely true — all of these texts, or even most of them, cannot go back to the Buddha’s life. -

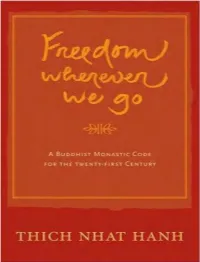

Freedom Wherever We Go: a Buddhist Monastic Code for the 21St Century

Table of Contents Title Page Preface Introduction Recitation Ceremony of the Bhikshu Precepts OPENING THE CEREMONY RECITATION CONCLUSION Recitation Ceremony of the Bhikshuni Precepts OPENING THE CEREMONY RECITATION CONCLUSION Sangha Restoration Offenses: Methods for Practicing Dwelling Apart, Beginning ... Text of Admitting a Sangha Restoration Offense Text of an Announcement to Be Made Every Day while Practicing Dwelling Apart Text to Request to Practice Six or Fifteen Days of Beginning Anew Text of an Announcement To Be Made Every Day while Practicing Six or Fifteen ... Text for Requesting Purification of a Sangha Restoration Offense Release and Expression of Regret Offense: Methods for Practicing Expressing ... Conclusion: Step by Step Copyright Page Preface THE PRATIMOKSHA is the basic book of training for Buddhist monastics. Training with the Pratimoksha, monastics purify their bodies and minds, cultivate love for all beings, and advance on the path of liberation. “Prati” means step-by-step. It can also be translated as “going in a direction.” “Moksha” means liberation. So “Pratimoksha” can be translated as freedom at every step. Each precept brings freedom to a specific area of our daily life. If we keep the precept of not drinking alcohol, for example, we have the freedom of not being drunk. If we keep the precept of not stealing, we have the freedom of not being in prison. The word “Pratimoksha” can also mean “in every place there is liberation.” We have titled this revised version of the Pratimoksha Freedom Wherever We Go to remind us that we are going in the direction of liberation. As a part of their training at Plum Village, fully ordained monks and nuns must spend at least five years studying the Vinaya, a vast and rich body of literature, that defines and organizes the life of the monastic community. -

THE BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES COMPARED with the BIBLE! !Robert Krueger! Presented To! !SYMPOSIUM: the UNIQUENESS of the CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURES! Dr

!THE BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES COMPARED WITH THE BIBLE! !Robert Krueger! Presented to! !SYMPOSIUM: THE UNIQUENESS OF THE CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURES! Dr. Martin Luther College! New Ulm, MN! !April 15-17, 1993! !THE BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES COMPARED WITH THE BIBLE! !Introduction! In regard to the title of this essay and the theme of the symposium, both of which refer to scrip- tures, it must be noted that there's a lot more material to be found on Buddhism than on Buddhist scriptures -- at least it's easier to find. Whole books as well as parts of books dealing with Bud- dhism often treat the matter of Buddhist scriptures only briefly or in passing. To be sure, there are Buddhist scriptures and reference is made to a Buddhist canon, but as we shall see, these are dif- !ferent than and not so clearly defined as are our Christian Scriptures and the Biblical canon.! An appreciation for the Bible may also be gained by just looking at the origin, history, and doctrine of Buddhism, and these areas are also important in considering the Buddhist scriptures. Thus we'll !first look at those aspects of Buddhism as well as at some important terms and concepts.! !1. History and Origin of Buddhism! The founder of Buddhism is Siddhartha Gautama (ca. 560-480 B.C.), a prince of the Sakyas, who became known as Sakyamuni, sage of the Sakya people, and as the Buddha, the Enlightened One. There are various stories about his birth and life and even his conception, but it is generally agreed that he grew up as a prince and a member of a privileged class, married, and had a son. -

Sects & Sectarianism

Sects & Sectarianism Also by Bhikkhu Sujato through Santipada A History of Mindfulness How tranquillity worsted insight in the Pali canon Beginnings There comes a time when the world ends… Bhikkhuni Vinaya Studies Research & reflections on monastic discipline for Buddhist nuns A Swift Pair of Messengers Calm and insight in the Buddha’s words Dreams of Bhaddā Sex. Murder. Betrayal. Enlightenment. The story of a Buddhist nun. White Bones Red Rot Black Snakes A Buddhist mythology of the feminine SANTIPADA is a non-profit Buddhist publisher. These and many other works are available in a variety of paper and digital formats. http://santipada.org Sects & Sectarianism The origins of Buddhist schools BHIKKHU SUJATO SANTIPADA SANTIPADA Buddhism as if life matters Originally published by The Corporate Body of the Buddha Education Foundation, Taiwan, 2007. This revised edition published in 2012 by Santipada. Copyright © Bhikkhu Sujato 2007, 2012. Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 2.5 Australia You are free to Share—to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the follow- ing conditions: Attribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). No Derivative Works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. With the understanding that: Waiver—Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Other Rights—In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license: o Your fair dealing or fair use rights; o The author’s moral rights; o Rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. -

1 Identity and the Coming-Of-Age Narrative

1 Identity and the Coming-of-Age Narrative A great deal has been said about the heart of a girl when she stands “where the brook and river meet,” but what she feels is negative; more interesting is the heart of a boy when just at the budding dawn of manhood. —James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man Little by little it has become clear to me that every great philosophy has been the confession of its maker, as it were his involuntary and unconscious autobiography. —Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil ead this—you’ll love it.” With these words, my mother hands me the “Rcopy of Little Women her aunt gave her when she was twelve and plants a seed that, three decades later, will grow into this study. At age twelve, I am beginning to balk at everything my mother suggests, but being constitu- tionally unable to resist any book, I grudgingly begin to read Louisa May Alcott’s novel. And like generations of girls before me, I fall in love with funny, feisty Jo and weep when Beth dies. Like Jo, I try to be good, but I have big dreams that distract me from my daily duties. Jo voices my own secret desires when she tells her sisters that she wants to do “something heroic or wonderful that won’t be forgotten when I’m dead. I don’t know what, but I’m on the watch for it and mean to astonish you all someday” (172). My mother keeps me steadily supplied with “underground” litera- ture—girls’ books—and while I feign disinterest, she is right. -

Coming of Age in Europe Today Jeffrey Jensen Arnett

“In the first half of the twentieth century, Europeans went from childhood to adolescence to young adulthood, and they reached a settled young adulthood by their early 20s. No more.” The Long and Leisurely Route: Coming of Age in Europe Today JEFFREY JENSEN ARNETT arie, age 28, is a student at a university tended pregnancy. Premarital sex soon became in Denmark, studying psychology. Cur- common and widely accepted as the norm. Also, Mrently she is in Italy, collecting interviews the economy’s basis changed from manufactur- for a research project, and living with her Brazil- ing to information and technology, and the new ian boyfriend Pablo, who is studying engineering economy led more and more young people to there. Her plan is to become a psychologist who pursue more and more education, often well into works with deaf children their 20s. The median marriage age rose steadily GLOBAL YOUTH and their families, but and soon became higher than ever before. It is now Sixth in a series much of her life is up in nearly 30 in most of Western Europe, and still ris- the air right now. How ing. Age at first childbirth became steadily later as much more education should she pursue, if any? well, and now instead of having three or four chil- She and Pablo would like to marry and have two dren most Europeans have two, or one, or none at children eventually, but when? Their lives are busy all. The total fertility rate across Europe is now just now. How could they fit children in amid their 1.4 children per woman. -

A Guide to Pali Texts, Commentaries, and Translations

A Guide to Pali Texts, Commentaries, and Translations The Books of the Pāli Canon (Tipiṭaka) and Commentaries (Aṭṭhakathā) Pāli Text Translation Vinaya Piṭaka [147-148, 160-162] The Book of the Discipline [SBB 10-11, 13-14, 20, 25] Sutta Piṭaka: Dīgha Nikāya [33-35] Dialogues of the Buddha [SBB 2-4] Majjhima Nikāya [60-63] Middle Length Sayings [SBB 5-6, Tr. 29-31] Saṃyutta Nikāya [93-98] The Book of Kindred Sayings [Tr. 7, 10, 13-14, 16] Aṅguttara Nikāya [3-8] The Book of Gradual Sayings [Tr. 22, 24-27] Khuddaka Nikāya: Khuddakapāṭha [52] The Minor Readings [Tr. 32] Dhammapada [23] Udāna [142] Verses of Uplift [SBB 8, 42] Itivuttaka [39] As It Was Said [SBB 8] Suttanipāta [127] Group of Discourses II / The Rhinoceros Horn [SBB 15, Tr. 45] Vimānavatthu [145, 168] Stories of the Mansions [SBB 12, 30] Petavatthu [89, 168] Stories of the Departed [SBB 12, 30] Theragāthā [132] Elders' Verses / Psalms of the Brethren [Tr. 38, 40] Therīgāthā [132] Elders' Verses / Psalms of the Sisters / Poems of Early Buddhist Nuns [Tr. 1, 4, 38, 40] Jātaka [42-44, 155-158] Niddesa [76-77] Paṭisambhidāmagga [86-87] The Path of Discrimination [Tr. 43] Apadāna [9-10] Buddhavaṃsa [166] The Chronicle of the Buddhas [SBB 9, 31] Cariyāpiṭaka [166] The Basket of Conduct [SBB 9, 31] Abhidhamma Piṭaka: Dhammasaṅgaṇī [31] Buddhist Psychological Ethics [Tr. 41] Vibhaṅga [144] The Book of Analysis [Tr. 39] Dhātukathā [32] Discourse on Elements [Tr. 34] Puggalapaññatti [91-92] A Designation of Human Types [Tr. 12] Kathāvatthu [48-49] Points of Controversy [Tr.