Acute Scrotum Medical Student Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urology / Gynecology Business Unit (UGBU) Strategy

Urology / Gynecology Business Unit (UGBU) Strategy Minoru Okabe Head of Uro/Gyn Business Unit Olympus Corporation March 30, 2016 Todayʼs Agenda 1.Business Overview 2.Recognition of Current Conditions 3.Market Trends 4.Business Strategies 5.Targets and Indicators 2 2016/3/30 No data copy / No data transfer permitted Todayʼs Agenda 1.Business Overview 2.Recognition of Current Conditions 3.Market Trends 4.Business Strategies 5.Targets and Indicators 3 2016/3/30 No data copy / No data transfer permitted Positioning of UG Business within Olympus 4 2016/3/30 No data copy / No data transfer permitted Distribution of Sales and Positioning FY2016 Net Sales (Forecast) Urology / Gynecology Business Unit (UGBU)* ET 72.0 Surgical Flexible and rigid endoscopes Benign prostatic hypertrophy and bladder Medical Business Devices* GI (ureteroscopes and cystoscopes) tumor resectoscopes and therapeutic FY2016 Net Sales electrodes (disposable) 337.4 205.6 (Forecast) ¥615.0 billion Urology field Flexible hysteroscopes * The figure for Surgical Devices net sales (¥205.6 billion) includes Stone treatment Gynecology field net sales of the Urology / Gynecology Business Unit (UGBU). devices (disposable) Resectoscopes Colposcopes 5 2016/3/30 No data copy / No data transfer permitted Applications and Characteristics of Major Products Field Urology Flexible Ureteroscope Stone Treatment Therapeutic Flexible Cystoscope Resectoscope URF-V2 Devices Electrodes (Disposable) CYF-VH OES Pro. (Disposable) Product Flexible ureteroscopes are used for Flexible cystoscopes are Resectoscopes are used to treat treating urinary stones. used to treat bladder benign prostatic hypertrophy and Feature Olympus flexible ureteroscopes have a tumors. bladder tumors. dominating edge realized by merging GI Olympus flexible Bipolar TURis electrodes endoscope technologies with the small cystoscopes have a (disposable) boast higher levels of diameter scope technologies of former dominating edge realized cutting safety and performance company Gyrus. -

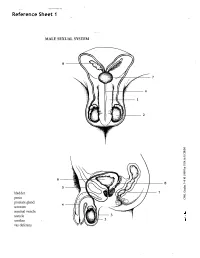

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

Trauma-Associated Pulmonary Laceration in Dogs—A Cross Sectional Study of 364 Dogs

veterinary sciences Article Trauma-Associated Pulmonary Laceration in Dogs—A Cross Sectional Study of 364 Dogs Giovanna Bertolini 1,* , Chiara Briola 1, Luca Angeloni 1, Arianna Costa 1, Paola Rocchi 2 and Marco Caldin 3 1 Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology Division, San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory, via dell’Industria 3, 35030 Veggiano, Padova, Italy; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (L.A.); [email protected] (A.C.) 2 Intensive Care Unit, San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory, via dell’Industria 3, 35030 Veggiano, Padova, Italy; [email protected] 3 Clinical Pathology Division, San Marco Veterinary Clinic and Laboratory, via dell’Industria 3, 35030 Veggiano, Padova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0498561098 Received: 5 March 2020; Accepted: 8 April 2020; Published: 12 April 2020 Abstract: In this study, we describe the computed tomography (CT) features of pulmonary laceration in a study population, which included 364 client-owned dogs that underwent CT examination for thoracic trauma, and compared the characteristics and outcomes of dogs with and without CT evidence of pulmonary laceration. Lung laceration occurred in 46/364 dogs with thoracic trauma (prevalence 12.6%). Dogs with lung laceration were significantly younger than dogs in the control group (median 42 months (interquartile range (IQR) 52.3) and 62 months (IQR 86.1), respectively; p = 0.02). Dogs with lung laceration were significantly heavier than dogs without laceration (median 20.8 kg (IQR 23.3) and median 8.7 kg (IQR 12.4 kg), respectively p < 0.0001). When comparing groups of dogs with thoracic trauma with and without lung laceration, the frequency of high-energy motor vehicle accident trauma was more elevated in dogs with lung laceration than in the control group. -

Reproductive System, Day 2 Grades 4-6, Lesson #12

Family Life and Sexual Health, Grades 4, 5 and 6, Lesson 12 F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System, day 2 Grades 4-6, Lesson #12 Time Needed 40-50 minutes Student Learning Objectives To be able to... 1. Distinguish reproductive system facts from myths. 2. Distinguish among definitions of: ovulation, ejaculation, intercourse, fertilization, implantation, conception, circumcision, genitals, and semen. 3. Explain the process of the menstrual cycle and sperm production/ejaculation. Agenda 1. Explain lesson’s purpose. 2. Use transparencies or your own drawing skills to explain the processes of the male and female reproductive systems and to answer “Anonymous Question Box” questions. 3. Use Reproductive System Worksheets #3 and/or #4 to reinforce new terminology. 4. Use Reproductive System Worksheet #5 as a large group exercise to reinforce understanding of the reproductive process. 5. Use Reproductive System Worksheet #6 to further reinforce Activity #2, above. This lesson was most recently edited August, 2009. Public Health - Seattle & King County • Family Planning Program • © 1986 • revised 2009 • www.kingcounty.gov/health/flash 12 - 1 Family Life and Sexual Health, Grades 4, 5 and 6, Lesson 12 F.L.A.S.H. Materials Needed Classroom Materials: OPTIONAL: Reproductive System Transparency/Worksheets #1 – 2, as 4 transparencies (if you prefer not to draw) OPTIONAL: Overhead projector Student Materials: (for each student) Reproductive System Worksheets 3-6 (Which to use depends upon your class’ skill level. Each requires slightly higher level thinking.) Public Health - Seattle & King County • Family Planning Program • © 1986 • revised 2009 • www.kingcounty.gov/health/flash 12 - 2 Family Life and Sexual Health, Grades 4, 5 and 6, Lesson 12 F.L.A.S.H. -

Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection Mimicking Testicular Malignancy In

270 Sex Transm Inf 1999;75:270 Chlamydia trachomatis infection mimicking Sex Transm Infect: first published as 10.1136/sti.75.4.270 on 1 August 1999. Downloaded from Case report: testicular malignancy in a young man cobblestone A M Ward, J H Rogers, C S Estcourt A young man with a low risk history for sexually transmitted diseases presented with an appar- ently longstanding, previously asymptomatic scrotal mass, highly suggestive of testicular malignancy on palpation. Ultrasound sited the lesion in the epididymis. Although there was no evidence of urethritis, chlamydia polymerase chain reaction testing was positive. Tumour mark- ers were negative. Complete clinical and radiological response was achieved after a long course of doxycycline treatment, without surgical exploration of the scrotum, confirming the diagnosis of chlamydial epididymitis. (Sex Transm Inf 1999;75:270) Keywords: testicular malignancy; Chlamydia trachomatis; epididymitis A 36 year old Chinese man presented with a 2 Fifteen months later the patient was asymp- day history of a sore scrotal lump. He had no tomatic with normal examination and ultra- urethral discharge or dysuria, and no history of sonography, and negative urinary chlamydia sexually transmitted diseases. He denied any PCR. He declined semen analysis. extramarital sexual partners since his marriage 5 years ago, but acknowledged four or five female partners before that. The couple had one child and were using condoms for contra- Discussion ception. Longstanding, subacute epididymitis, present- Examination revealed left sided scrotal ing with a painless scrotal mass, and without swelling and a mildly tender mass, inseparable evidence of urethritis, is an unusual complica- from the lower pole of the left testis, with an tion of chlamydial infection.1 irregular surface and rock hard consistency. -

Case Report a Case of a Patient Who Is Diagnosed with Mild Acquired Hemophilia a After Tooth Extraction Died of Acute Subdural Hematoma Due to Head Injury

Hindawi Case Reports in Dentistry Volume 2018, Article ID 7185263, 3 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7185263 Case Report A Case of a Patient Who Is Diagnosed with Mild Acquired Hemophilia A after Tooth Extraction Died of Acute Subdural Hematoma due to Head Injury Tomohisa Kitamura,1 Tsuyoshi Sato ,1 Eiji Ikami,1 Yosuke Fukushima,1 and Tetsuya Yoda2 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Saitama Medical University, 38 Moro-hongou, Moroyama-machi, Iruma-gun, Saitama 350-0495, Japan 2Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence should be addressed to Tsuyoshi Sato; [email protected] Received 13 September 2018; Revised 12 November 2018; Accepted 25 November 2018; Published 9 December 2018 Academic Editor: Yuk-Kwan Chen Copyright © 2018 Tomohisa Kitamura et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background. Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare disorder which results from the presence of autoantibodies against blood coagulation factor VIII. The initial diagnosis is based on the detection of an isolated prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) with negative personal and family history of bleeding disorder. Definitive diagnosis is the identification of reduced FVIII levels with evidence of FVIII neutralizing activity. Case report. We report a case of a 93-year-old female who was diagnosed as AHA after tooth extraction at her home clinic. Prolongation of aPTT and a reduction in factor VIII activity levels were observed with the presence of factor VIII inhibitor. -

Blood Counts

Medicare National Coverage Determinations (NCD) Coding Policy Manual and Change Report April 2009 Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory Services Health & Human Services Department Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 7500 Security Boulevard Baltimore, MD 21244 CMS Email Point of Contact: [email protected] TDD 410.786.0727 Fu Associates, Ltd. Medicare National Coverage Determinations (NCD) Coding Policy Manual and Change Report This is CMS Logo. NCD Manual Changes Date Reason Release Change Edit The following section represents NCD Manual updates for April 2009. 04/01/09 Per CR 6383 add 2009200 *525.71 Osseointegration *190.15 Blood Counts ICD-9-CM codes failure of dental implant 525.71, 525.72 and 525.73 to the list of ICD-9-CM codes that *525.72 Post- do not support osseointegration Medical necessity for biological failure of the Blood Counts dental implant NCD. *525.73 Post- Transmittal # 1684 osseointegration mechanic failure of dental implant 04/01/09 Per CR 6383 add 2009200 *535.70 Eosinophilic *190.16 Partial ICD-9-CM codes gastritis, without Thromboplastin Time 535.70 and 535.71 to mention of obstruction (PTT) the list of ICD-9-CM codes covered by Medicare for the *535.71 Eosinophilic Partial gastritis, with Thromboplastin Time obstruction NCD. Transmittal # 1684 04/01/09 Per CR 6383 add 2009200 *414.3 Coronary *190.17 Prothrombin ICD-9-CM codes atherosclerosis due to Time 414.3, 535.70 and lipid rich plaque 535.71 to the list of ICD-9-CM codes *535.70 Eosinophilic covered by Medicare gastritis, without mention for the Prothrombin of obstruction Time NCD. -

Non-Certified Epididymitis DST.Pdf

Clinical Prevention Services Provincial STI Services 655 West 12th Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 4R4 Tel : 604.707.5600 Fax: 604.707.5604 www.bccdc.ca BCCDC Non-certified Practice Decision Support Tool Epididymitis EPIDIDYMITIS Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency and requires immediate consultation. It can mimic epididymitis and must be considered in all people presenting with sudden onset, severe testicular pain. Males less than 20 years are more likely to be diagnosed with testicular torsion, but it can occur at any age. Viability of the testis can be compromised as soon as 6-12 hours after the onset of sudden and severe testicular pain. SCOPE RNs must consult with or refer all suspect cases of epididymitis to a physician (MD) or nurse practitioner (NP) for clinical evaluation and a client-specific order for empiric treatment. ETIOLOGY Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis, with bacterial and non-bacterial causes: Bacterial: Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) coliforms (e.g., E.coli) Non-bacterial: urologic conditions trauma (e.g., surgery) autoimmune conditions, mumps and cancer (not as common) EPIDEMIOLOGY Risk Factors STI-related: condomless insertive anal sex recent CT/GC infection or UTI BCCDC Clinical Prevention Services Reproductive Health Decision Support Tool – Non-certified Practice 1 Epididymitis 2020 BCCDC Non-certified Practice Decision Support Tool Epididymitis Other considerations: recent urinary tract instrumentation or surgery obstructive anatomic abnormalities (e.g., benign prostatic -

Male Infertility Low Testosterone

Male Infertility low testosterone. One of the first academic medical centers in the Both are fellowship-trained, male reproductive urologists prepared to deal nation to create a sperm bank continues to lead with the most complex infertility cases and the way in male infertility research and in complex to perform complex microsurgeries, such as vasectomy reversals and testicular-sperm clinical care. extraction. Partnering with URMC’s female infertility experts, the male infertility clinic An andrology lab and sperm bank were bank, today URMC’s Urology department is part of a designated in-vitro fertilization created more than 30 years ago at the now boasts two fellowship-trained male center of excellence in New York state. University of Rochester Medical Center infertility specialists—Jeanne H. O’Brien, (URMC). Grace M. Centola, Ph.D., M.D. and J. Scott Gabrielsen, M.D., Ph.D. Complex Care H.C.L.D., former associate professor of A nationally recognized male-infertility URMC’s male infertility clinicians see a Obstetrics and Gynecology at URMC, expert, O’Brien has received numerous growing number of patients with male- was instrumental in creating the bank, in awards and recognitions for both her factor infertility, such as decreased collaboration with Robert Davis, M.D., clinical and basic science research work. sperm counts, motility or morphology. and Abraham Cockett, M.D., from the Gabrielsen focuses on male reproductive The first steps in the care process are a Department of Urology. health, including male infertility, erectile baseline semen analysis, coupled with Building on the groundbreaking sperm dysfunction, male sexual dysfunction and an understanding of a patient’s health 4 UR Medicine | Department of Urology | urology.urmc.edu history. -

Ultrasonography of the Scrotum in Adults

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Radiology Publications and Presentations Radiology 2016-07-01 Ultrasonography of the scrotum in adults Anna L. Kuhn University of Massachusetts Medical School Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/radiology_pubs Part of the Male Urogenital Diseases Commons, Radiology Commons, Reproductive and Urinary Physiology Commons, Urogenital System Commons, and the Urology Commons Repository Citation Kuhn AL, Scortegagna E, Nowitzki KM, Kim YH. (2016). Ultrasonography of the scrotum in adults. Radiology Publications and Presentations. https://doi.org/10.14366/usg.15075. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/radiology_pubs/173 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Radiology Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ultrasonography of the scrotum in adults Anna L. Kühn, Eduardo Scortegagna, Kristina M. Nowitzki, Young H. Kim Department of Radiology, UMass Memorial Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA, USA REVIEW ARTICLE Ultrasonography is the ideal noninvasive imaging modality for evaluation of scrotal http://dx.doi.org/10.14366/usg.15075 abnormalities. It is capable of differentiating the most important etiologies of acute scrotal pain pISSN: 2288-5919 • eISSN: 2288-5943 and swelling, including epididymitis and testicular torsion, and is the imaging modality of choice Ultrasonography 2016;35:180-197 in acute scrotal trauma. In patients presenting with palpable abnormality or scrotal swelling, ultrasonography can detect, locate, and characterize both intratesticular and extratesticular masses and other abnormalities. -

What Is a Hydrocelectomy, Spermatocelectomy and Epididymal Cystectomy? a Hydrocele Is an Abnormal Fluid Collection Between the Outer Tissue Layers of the Testicle

Dr. Kevin G. Kwan, BSc (Hons), MD, FRCS(C) Minimally Invasive Surgery and General Urology Assistant Clinical Professor Division of Urology, Department of Surgery McMaster University Chief of Surgery, Milton District Hospital Georgetown Hospital • Milton District Hospital • Oakville Trafalgar Memorial Hospital Suite 205 - 311 Commercial Street • Milton • Ontario • L9T 3Z9 • Tel: (905) 875-3920 • Fax: (905) 875-4340 Email: [email protected] • Web: www.haltonurology.com What is a hydrocelectomy, spermatocelectomy and epididymal cystectomy? A hydrocele is an abnormal fluid collection between the outer tissue layers of the testicle. These tissue layers naturally secrete fluid and when this fluid is not reabsorbed, as it usually would be, a fluid collection or hydrocele forms. The cause of most hydroceles is unknown, although some may be related to trauma, infection, or past surgery. A spermatocele is a cyst-like sac that is usually attached to the epididymis, the tube that sits behind the testicle and stores sperm. The sac of a spermatocele is filled with sperm. The exact cause of a spermatocele is unknown but it is thought that injury and obstruction may play a part in their formation. An epididymal cyst is much the same as a spermatocele. However, the sac attached to the epididymis is a true cyst and is filled with cystic fluid and not sperm. A hydrocelectomy is an operation to treat a hydrocele. An incision is made in the scrotum and the testicle containing the hydrocele is lifted out. The sac is then removed and the remaining tissue edges are stitched back. The tissue edges then heal onto themselves and the surrounding vessels naturally reabsorb any fluid produced. -

Post-Orgasmic Illness Syndrome: a Closer Look

Indonesian Andrology and Biomedical Journal Vol. 1 No. 2 December 2020 Post-orgasmic Illness Syndrome: A Closer Look William1,2, Cennikon Pakpahan2,3, Raditya Ibrahim2 1 Department of Medical Biology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya, Jakarta, Indonesia 2 Andrology Specialist Program, Department of Medical Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga – Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia 3 Ferina Hospital – Center for Reproductive Medicine, Surabaya, Indonesia Received date: Sep 19, 2020; Revised date: Oct 6, 2020; Accepted date: Oct 7, 2020 ABSTRACT Background: Post-orgasmic illness syndrome (POIS) is a rare condition in which someone experiences flu- like symptoms, such as feverish, myalgia, fatigue, irritabilty and/or allergic manifestation after having an orgasm. POIS can occur either after intercourse or masturbation, starting seconds to hours after having an orgasm, and can be lasted to 2 - 7 days. The prevalence and incidence of POIS itself are not certainly known. Reviews: Waldinger and colleagues were the first to report cases of POIS and later in establishing the diagnosis, they proposed 5 preliminary diagnostic criteria, also known as Waldinger's Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria (WPDC). Symptoms can vary from somatic to psychological complaints. The mechanism underlying this disease are not clear. Immune modulated mechanism is one of the hypothesis that is widely believed to be the cause of this syndrome apart from opioid withdrawal and disordered cytokine or neuroendocrine responses. POIS treatment is also not standardized. Treatments includeintra lymphatic hyposensitization of autologous semen, non-steroid anti-inflamation drugs (NSAIDs), steroids such as Prednisone, antihistamines, benzodiazepines, hormones (hCG and Testosterone), alpha-blockers, and other adjuvant medications.