A Note from Howard Bryant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Giants 2012 Season Recap 2012 New York Giants

NEW YORK GIANTS 2012 SEASON RECAP The 2012 Giants finished 9-7 and in second place in the NFC East. It was the eighth consecutive season in which the Giants finished .500 or better, their longest such streak since they played 10 seasons in a row without a losing record from 1954-63. The Giants finished with a winning record for the third consecutive season, the first time they had done that since 1988-90 (when they were 10-6, 12-4, 13-3). Despite extending those streaks, they did not earn a postseason berth. The Giants lost control of their playoff destiny with back-to-back late-season defeats in Atlanta and Baltimore. They routed Philadelphia in their finale, but soon learned they were eliminated when Chicago beat Detroit. The Giants compiled numerous impressive statistics in 2012. They scored 429 points, the second-highest total in franchise history; the 1963 Giants scored 448. The 2012 season was the fifth in the 88-year history of the franchise in which the Giants scored more than 400 points. The Giants scored a franchise- record 278 points at home, shattering the old mark of 248, set in 2007. In their last three home games – victories over Green Bay, New Orleans and Philadelphia – the Giants scored 38, 52 and 42 points. The 2012 team allowed an NFL-low 20 sacks. The Giants were fourth in the NFL in both takeaways (35, four more than they had in 2011) and turnover differential (plus-14, a significant improvement over 2011’s plus-7). The plus-14 was the Giants’ best turnover differential since they were plus-25 in 1997. -

Cheap Jerseys on Sale Including the High Quality Cheap/Wholesale Nike

Cheap jerseys on sale including the high quality Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps offer low price with free shipping!The Giants put a dismal 2009 season behind them and opened New Meadowlands Stadium so that you have an all in one 31-18 season-opening win even more than the Carolina Panthers. But they has been doing never ever necessarily need to panic about element upon preference.In a game as chaotic as the rainy weather, there are already tipped passes and a multi function ostracized hit interceptions and aches and pains slips and sacks,fumbles and follies of all sort. But in the stop,going to be the Giants emerged allowing an individual an all in one needed win for more information regarding chart a positive greens and for 2010 after they lost eight to do with their final 11 games on 2009.The Giants answered questions about an all in one defense that was renovated on such basis as going to be the new coordinator Perry Fewell and additions in the secondary,all of these had an all in one strong performance so that you have Terrell Thomas, Deon Grant and KennyPhillips all of them are intercepting Carolina quarterback Matt Moore.Meanwhile, Eli Manning threw about three touchdown passes, completing 20 of 30 passes and then for 263 yards. He would certainly have been significantly more triumph had his receivers held onto going to be the ball. All about three to do with his interceptions came as an all in one result relating to deflections -

Forced Slave Camps Draft Results 13-Feb-2004 03:37 PM Eastern

WWW.RTSPORTS.COM Forced Slave Camps Draft Results 13-Feb-2004 03:37 PM Eastern Forced Slave Camps Draft BRICK Conference Mon., Sep 1 2003 1:00:00 PM Rounds: 16 Round 1 Round 6 #1 Buckweet - Ricky Williams, RB, MIA #1 Jammin Blues - Donte' Stallworth, WR, NOR #2 Sharks - St. Louis Rams, QB, STL #2 DRED ED's - Todd Heap, TE, BAL #3 Heidelville Humpers - LaDainian Tomlinson, RB, SDG #3 Boltz - Rod Smith, WR, DEN #4 Psychic Psychos - Marshall Faulk, RB, STL #4 Willy's Lumpers - Green Bay Packers, QB, GNB #5 Fast Attack Boomers - Clinton Portis, RB, DEN #5 Keystone Kops - Shannon Sharpe, TE, DEN #6 Keystone Kops - Shaun Alexander, RB, SEA #6 Fast Attack Boomers - Anthony Thomas, RB, CHI #7 Willy's Lumpers - Priest Holmes, RB, KAN #7 Psychic Psychos - Derrick Mason, WR, TEN #8 Boltz - Deuce McAllister, RB, NOR #8 Heidelville Humpers - Marty Booker, WR, CHI #9 DRED ED's - Edgerrin James, RB, IND #9 Sharks - Jerry Rice, WR, OAK #10 Jammin Blues - Terrell Owens, WR, SFO #10 Buckweet - Tim Brown, WR, OAK Round 2 Round 7 #1 Jammin Blues - Ahman Green, RB, GNB #1 Buckweet - James Stewart, RB, DET #2 DRED ED's - Marvin Harrison, WR, IND #2 Sharks - Chad Johnson, WR, CIN #3 Boltz - Randy Moss, WR, MIN #3 Heidelville Humpers - Jerry Porter, WR, OAK #4 Willy's Lumpers - Travis Henry, RB, BUF #4 Psychic Psychos - New England Patriots, QB, NWE #5 Keystone Kops - Charlie Garner, RB, OAK #5 Fast Attack Boomers - Keyshawn Johnson, WR, TAM #6 Fast Attack Boomers - Eric Moulds, WR, BUF #6 Keystone Kops - James Thrash, WR, PHI #7 Psychic Psychos - Fred Taylor, -

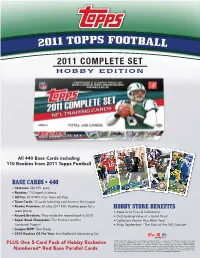

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

New York Giants: 2014 Financial Scouting Report

New York Giants: 2014 Financial Scouting Report Written By: Jason Fitzgerald, Overthecap.com Date: January 10, 2014 e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Welcome to one of the newest additions to the Over the Cap website: the offseason Financial Scouting Report, which should help serve as a guide to a teams’ offseason planning for the 2014 season. This report focuses on the New York Giants and time permitting I will try to have a report for every team between now and the start of free agency in March. If you would like copies of other reports that are available please either e-mail me or visit the site overthecap.com The Report Contains: Current Roster Overview 2013 Team Performances Compared to NFL Averages Roster Breakdown Charts Salary Cap Outlook Unrestricted and Restricted Free Agents Potential Salary Cap Cuts NFL Draft Selection Costs and Historical Positions Selected Salary Cap Space Extension Candidates Positions of Need and Possible Free Agent Targets Any names listed as potential targets in free agency are my own opinions and do not reflect any “inside information” reflecting plans of various teams. It is simply opinion formed based on player availability and my perception of team needs. Player cost estimates are based on potential comparable players within the market. OTC continues to be the leading independent source of NFL salary cap analysis and we are striving to continue to produce the content and accurate contract data that has made us so popular within the NFL community. The report is free for download and reading, but if you find the report useful and would like to help OTC continue to grow we would appreciate the “purchase” of the report for just $1.00 by clicking the Paypal link below. -

Office of Communications & Media Relations

Office of Communications & Media Relations IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT EVA PICKENS (713) 313-4205 o Strahan’s Induction into 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame Big for TSU…Big for Houston Seven NFL legends including Texas Southern’s own Michael Strahan will be formally enshrined into the Pro Football Hall of Fame during a memorable ceremony held at Pro Football Hall of Fame Field on Saturday, Aug. 2, 2014 in Canton, Ohio. The former NFL player and Super Bowl champion Strahan, has put Texas Southern University in the national spotlight as host of the NFL pregame show on Fox, co-host on ABC’s "Live with Kelly & Michael" and a member of ABC’s “Good Morning America” team. After starring at Westbury High School, Texas Southern University was the only school that offered Strahan a scholarship to play football. Focus, determination and hard work propelled him to be drafted in 1993 by the New York Giants. He would spend the next 15 years carving out a hall of fame worthy career that included a Super Bowl championship, a Defensive Player of the Year award, seven Pro Bowls, and breaking the NFL single-season record with 22.5 sacks. “We are extremely proud of Strahan’s induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame,” said Dr. John Rudley, Texas Southern University president. “This honor is just further proof that ‘Excellence in Achievement’ is more than a mantra at Texas Southern, it is a way of life.” Another Texas Southern alumnus Tony Wyllie, who currently holds the position of Senior Vice President of Communications for the Washington Redskins says, “I was prepared for this announcement because Mike is so deserving of the Hall. -

NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl Has Grown to Become One of the Largest Sports Spectacles in the United States

/ The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Chelsea Police Thesis Advisor Mr. Neil Behrman Signed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2016 Expected Date of Graduation May 2016 §pCoJI U ncler.9 rod /he. 51;;:, J_:D ;l.o/80J · Z'7 The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making ~0/G , PG.5 Abstract Originally known as the AFL-NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl has grown to become one of the largest sports spectacles in the United States. Cities across the cotintry compete for the right to host this prestigious event. The reputation of such an occasion has caused an increase in demand and price for tickets, making attendance nearly impossible for the average fan. As a result, the National Football League has implemented free events for local residents and out-of-town visitors. This, along with broadcasting the game, creates an inclusive environment for all fans, leaving a lasting legacy in the world of professional sports. This paper explores the growth of the Super Bowl from a novelty game to one of the country' s most popular professional sporting events. Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I would like to thank my parents for their unending support. Thank you for allowing me to try new things and learn from my mistakes. Most importantly, thank you for believing that I have the ability to achieve anything I desire. Second, I would like to thank my brother for being an incredible role model. -

Afc Notes Patriots Aim to Clinch Seventh

AFC NOTES FOR USE AS DESIRED FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION, 11/24/15 CONTACT: JON ZIMMER http://twitter.com/NFL345 PATRIOTS AIM TO CLINCH SEVENTH CONSECUTIVE AFC EAST TITLE The New England Patriots have reached 10-0 for the second time in franchise history and first time since 2007, when they finished the regular season undefeated and advanced to Super Bowl XLII. “It feels good to win,” said quarterback TOM BRADY after the Patriots’ 20-13 win against the Bills on Monday Night Football. “It's obviously hard to get to this point (10-0). So, we'll just keep fighting.” The Patriots are the fourth defending Super Bowl champion to start a season 10-0, joining Green Bay (13-0 in 2011), Denver (13-0 in 1998) and San Francisco (10-0 in 1990). This weekend, New England can clinch its seventh consecutive division title, which would tie the 1973-79 Los Angeles Rams for the longest streak in NFL history. The Patriots will travel to Denver to face the Broncos in a battle of first-place teams in primetime on Sunday Night Football (8:30 PM ET, NBC). The Patriots, who also won five consecutive division titles from 2003-2007, are the only team in NFL history to win 11 division championships in a 12-year span. The teams with the most consecutive division titles: TEAM SEASONS CONSECUTIVE DIVISION TITLES Los Angeles Rams 1973-79 7 New England Patriots 2009-14 6* Cleveland Browns 1950-55 6 Dallas Cowboys 1966-71 6 Minnesota Vikings 1973-78 6 Pittsburgh Steelers 1974-79 6 *Active streak; can clinch AFC East title in Week 12 Since the NFL instituted the 16-game schedule in 1978, five teams have clinched a division a title after 11 games. -

Eli Manning Calling Time on 16-Year NFL Career One of Five Players in History with at Least Two Super Bowl Mvps

44 Friday Sports Friday, January 24, 2020 Eli Manning calling time on 16-year NFL career One of five players in history with at least two Super Bowl MVPs NEW YORK: Quarterback Eli Manning, who Manning, younger brother of another super- won two Super Bowls and was the face of the star quarterback, Peyton Manning, started 234 New York Giants franchise for more than a games for the Giants — the fourth most by a decade, is retiring from the NFL, the team said quarterback for one club. He was drafted first Wednesday. The Giants said Manning — who overall by the San Diego Chargers in the 2004 spent all 16 seasons of his NFL career with the draft but he made it known he didn’t want to play Giants after a draft-day trade in 2004 — will in San Diego and was traded to the Giants. formally announce his retirement on Wednesday. “For 16 seasons, Eli Manning defined what it ‘A privilege to coach’ is to be a New York Giant both on and off the He finishes his career seventh all-time with field,” said John Mara, the Giants’ president and 366 touchdown passes, seventh in passing yards chief executive officer. “Eli is our only two-time with 57,023, and tied with Joe Montana for 11th Super Bowl MVP and one of the very best play- in career wins with 117. But he’ll be best remem- ers in our franchise’s history. He represented our bered for two of the biggest upsets in Super Bowl franchise as a consummate professional with history. -

Game, Set, Rematch

B2 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2012 THE ADVOCATE-MESSENGER SPORTS/SCORECARD WWW.AMNEWS.COM AFC-NFC Championships 1. Patriots (15-3) F eel they are team of destiny; riding a 10-game win streak into Super Bowl. Sunday, Jan. 22 New England 23 Baltimore 20 2. Giants (12-7) E li Manning headed to his big brother Peyton’s adopted hometown of Indy. N.Y. Giants 20 San Francisco (ot) 17 3. Ravens (13-5) Ray Lewis says AFC title game loss was “absolutely not” his last game. Divisional Round 4. 49ers (14-4) Kyle Williams’ botched punts hurt but San Fran was 1-of-13 on 3rd down. Saturday, Jan. 14 5. Packers (15-2) Jim Irwin, radio voice of the Packers for 30 seasons, passes away at 77. San Francisco 36 New Orleans 32 New England 45 Denver 10 6. Saints (14-4) Sean Payton, Mickey Loomis confident free agent Drew Brees will re-sign. Sunday, Jan. 15 7. Texans (11-7) Center Chris Myers, DE Antonio Smith added to Pro Bowl roster as alternates. Baltimore 20 Houston 13 8. Broncos (9-9) Tim Tebow sings, performs on stage with country music star Brad Paisley. N.Y. Giants 37 Green Bay 20 9. Steelers (12-5) Interview former Chiefs coach Todd Haley for offensive coordinator vacancy. Wild Card Round Saturday, Jan. 7 10. Lions (10-7) Cam Newton, not Matt Stafford, named Eli Manning’s Pro Bowl replacement. Houston 31 Cincinnati 10 11. Falcons (10-7) Hire Mike Nolan as defensive coordinator; fire DB coach Alvin Reynolds. New Orleans 45 Detroit 28 12. -

LETTER to DISTRICT JUDGE by Arizona Cardinals, Inc., Atlanta

Brady et al v. National Football League et al Doc. 115 Att. 1 Attachment 1 – Plaintiffs’ Proposed Order that they emailed to Chambers on April 26, 2011 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MINNESOTA TOM BRADY, DREW BREES, VINCENT JACKSON, BEN LEBER, LOGAN MANKINS, PEYTON MANNING, VON MILLER, BRIAN ROBISON, OSI UMENYIORA, and MIKE VRABEL, individually, and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. No. 0:11-cv-00639-SRN-JJG NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE, et al., Defendants. [PROPOSED] ORDER ON PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION For the reasons explained in this Court’s memorandum opinion dated April 25, 2011, the Court has granted the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction. IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED that Defendants National Football League, Arizona Cardinals, Inc., Atlanta Falcons Football Club LLC, Baltimore Ravens Limited Partnership, Buffalo Bills, Inc., Panthers Football LLC, Chicago Bears Football Club, Inc., Cincinnati Bengals, Inc., Cleveland Browns LLC, Dallas Cowboys Football Club, Ltd., Denver Broncos Football Club, Detroit Lions, Inc., Green Bay Packers, Inc., Houston NFL Holdings LP, Indianapolis Colts, Inc., Jacksonville Jaguars Ltd., Kansas City Chiefs Football Club, Inc., Miami Dolphins, Ltd., Minnesota Vikings Football Club LLC, New England Patriots, LP, New Orleans Louisiana Saints, LLC, New York Football Giants, Inc., New York Jets Football Club, Inc., Oakland Raiders LP, Philadelphia Eagles LP, Pittsburgh Steelers Sports, Inc., San Diego Chargers Football Co., San Francisco Forty Niners Dockets.Justia.com Attachment 1 – Plaintiffs’ Proposed Order that they emailed to Chambers on April 26, 2011 Ltd., Football Northwest LLC, The Rams Football Co. LLC, Buccaneers Limited Partnership, Tennessee Football, Inc., and Washington Football Inc., as well as their officers, employees, and agents and any persons or entities acting under their direction and control, are restrained and enjoined, for one year from the effective date of this preliminary injunction or until further order from this Court, from: 1. -

Featuring Tom Coughlin and Steve Spagnuolo

All the Best Podcast Episode 57: “Team Above Self” Featuring Former New York Giants Head Coach Tom Coughlin and Kansas City Chiefs Defensive Coordinator Steve Spagnuolo Sam: May 15th, 1968, I sent this telegram to my Yale baseball coach, Ethan Allen, the day he announced his retirement. All of us 300 hitters read today's "Times" with mixed emotions. I regret that Yale will be losing a great coach but happiness is knowing that you will continue to make a significant contribution to American sports, in whatever you decide to do. One of the great experiences of my own was playing at Yale during your first three years. I will never forget the spirit we had, the pure enjoyment of it all, and the great benefits I felt that I got as a person playing for a wonderful coach, a real gentleman, and most importantly, a warm and close friend. Bar joins me in sending our love to Doris, on this significant occasion, my thanks to you for everything you did for me and for Yale baseball. Congratulations, and warmest regards, George H. W. Bush. George: In the first place, I believe that character is a part of being President. Barbara: And life really must have joy. Sam: This is "All the Best." The official podcast of the George and Barbara Bush Foundation. I'm your host, Sam LeBlond, one of their many grandchildren. Here, we celebrate the legacy of these two incredible Americans through friends, family, and the foundation. This is "All the Best." George: I remember something my dad taught me.