The Construction Challenge in Greater Manchester: Employment, Skills and Training

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

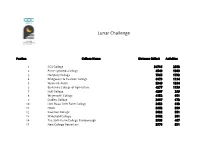

Lunar Challenge

Lunar Challenge Postion College Name Distance (Miles) Activities 1 SGS College 34786 2503 2 Peter Symonds College 8549 1069 3 Hartpury College 7565 1733 4 Bridgwater & Taunton College 6873 1194 5 Wyke 6th Form 5349 1594 6 Berkshire College of Agriculture 4277 1159 7 Hull College 4207 299 8 Weymouth College 4152 661 9 Dudley College 3987 673 10 Hills Road Sixth Form College 3953 693 11 HSDC 3902 599 12 Xaverian College 3632 591 13 Wakefield College 3602 301 14 The Sixth Form College Farnborough 3593 467 15 New College Pontefract 3578 531 16 Reaseheath College 3363 778 17 DN Colleges Group 3311 377 18 Barton Peveril College 3279 1091 19 Chichester College 3234 651 20 BMET College 3171 670 21 Preston's College 2981 402 22 Sandwell College 2791 406 23 Derby College 2534 216 24 Nottingham College 2490 360 25 Hopwood Hall 2421 533 26 Petroc 2378 332 27 City College Norwich Group 2377 481 28 Wiltshire College 2295 223 29 Royal National College for the Blind 2235 183 30 Stoke on Trent Sixth Form 2182 621 31 Furness College 2157 348 32 North Hertfordshire College 2110 464 33 Runshaw College 2052 548 34 AoC 2052 346 35 Lincoln College 2037 400 36 Kingston College 2007 247 37 Weston College 1907 358 38 Long Road 1891 282 39 Blackburn College 1862 267 40 Writtle College University 1821 126 41 Aquinas College 1797 227 42 New College Durham 1780 376 43 Tyne Coast College 1779 288 44 East Norfolk Sixth Form College 1778 437 45 Middlesborugh 1657 198 46 Walsall College 1591 361 47 Yeovil College 1550 285 48 Leeds College of Building 1521 187 49 Winstanley -

The Further Education and Sixth-Form Colleges 16

Greater Manchester Area Review Final report November 2016 Contents Background 4 The needs of the Greater Manchester area 5 Demographics and the economy 5 Patterns of employment and future growth 10 Jobs growth to 2022 12 Feedback from LEPs, employers, local authorities and students 13 The quantity and quality of current provision 14 Performance of schools at Key Stage 4 15 Schools with sixth-forms 15 The further education and sixth-form colleges 16 The current offer in the colleges 18 Quality of provision and financial sustainability of colleges 20 Higher education in further education 22 Provision for students with Special Educational (SEN) and high needs 23 Apprenticeships and apprenticeship providers 24 The need for change 25 The key areas for change 26 Initial options raised during visits to colleges 27 Criteria for evaluating options and use of sector benchmarks 29 Assessment criteria 29 FE sector benchmarks 29 Recommendations agreed by the steering group 31 Oldham, Stockport and Tameside Colleges 32 Bolton College, Bury College and the University of Bolton 32 Trafford College 33 Hopwood Hall College 33 Salford City College 34 Wigan and Leigh College 34 Aquinas College 35 Cheadle and Marple College Network 35 2 Ashton Sixth Form College 35 Oldham Sixth Form College 36 Rochdale Sixth Form College 36 Holy Cross Catholic Sixth Form College 36 Bolton Sixth Form College 37 Winstanley Sixth Form College 37 St John Rigby Sixth Form College 37 Xaverian Sixth Form College 38 Loreto Sixth Form College 38 Formation of a strategic planning group for Manchester 38 Development of a proposal for an Institute of Technology 39 An apprenticeship delivery group 39 Conclusions from this review 40 Next steps 42 3 Background0B In July 2015, the government announced a rolling programme of around 40 local area reviews, to be completed by March 2017, covering all general further education colleges and sixth-form colleges in England. -

College Employer Satisfaction League Table

COLLEGE EMPLOYER SATISFACTION LEAGUE TABLE The figures on this table are taken from the FE Choices employer satisfaction survey taken between 2016 and 2017, published on October 13. The government says “the scores calculated for each college or training organisation enable comparisons about their performance to be made against other colleges and training organisations of the same organisation type”. Link to source data: http://bit.ly/2grX8hA * There was not enough data to award a score Employer Employer Satisfaction Employer Satisfaction COLLEGE Satisfaction COLLEGE COLLEGE responses % responses % responses % CITY COLLEGE PLYMOUTH 196 99.5SUSSEX DOWNS COLLEGE 79 88.5 SANDWELL COLLEGE 15678.5 BOLTON COLLEGE 165 99.4NEWHAM COLLEGE 16088.4BRIDGWATER COLLEGE 20678.4 EAST SURREY COLLEGE 123 99.2SALFORD CITY COLLEGE6888.2WAKEFIELD COLLEGE 78 78.4 GLOUCESTERSHIRE COLLEGE 205 99.0CITY COLLEGE BRIGHTON AND HOVE 15088.0CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE COLLEGE6178.3 NORTHBROOK COLLEGE SUSSEX 176 98.9NORTHAMPTON COLLEGE 17287.8HEREFORDSHIRE AND LUDLOW COLLEGE112 77.8 ABINGDON AND WITNEY COLLEGE 147 98.6RICHMOND UPON THAMES COLLEGE5087.8LINCOLN COLLEGE211 77.7 EXETER COLLEGE 201 98.5CHESTERFIELD COLLEGE 20687.7WEST NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COLLEGE242 77.4 SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE AND STROUD COLLEGE 215 98.1ACCRINGTON AND ROSSENDALE COLLEGE 14987.6BOSTON COLLEGE 61 77.0 TYNE METROPOLITAN COLLEGE 144 97.9NEW COLLEGE DURHAM 22387.5BURY COLLEGE121 76.9 LAKES COLLEGE WEST CUMBRIA 172 97.7SUNDERLAND COLLEGE 11487.5STRATFORD-UPON-AVON COLLEGE5376.9 SWINDON COLLEGE 172 97.7SOUTH -

Framework Users (Clients)

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

Greater Manchester Area Review: College Annex

Greater Manchester Area Review College annex November 2016 Contents1 Aquinas College 3 Ashton-under-Lyne Sixth Form College 4 Bolton Sixth Form College 5 Cheadle and Marple Sixth Form College 6 Holy Cross Catholic Sixth Form College 7 Loreto Sixth Form College 8 Oldham Sixth Form College 9 Rochdale Sixth Form College 10 St John Rigby Sixth Form College 11 Winstanley Sixth Form College 12 Xaverian Sixth Form College 13 Bolton College 14 Bury College 15 Hopwood Hall College 16 Salford City College 17 Stockport College 18 Tameside College 19 The Manchester College 20 The Oldham College 21 Trafford College 22 Wigan and Leigh College 23 1 Please note that the information on the colleges included in this annex relates to the point at which the review was undertaken. No updates have been made to reflect subsequent developments or appointments since the completion of the review. 2 Aquinas College Type: Sixth-form college Location: The college is based in Stockport Local Enterprise Partnership: Greater Manchester Principal: Danny Pearson Corporation Chair: Tom McGee Main offer includes: The college offers academic and technical education provision for 16-18 year olds as well as some part-time provision for adults (19+), two evenings each week Details about the college offer can be reviewed on the college website Partnerships: The college is a member of the 6 colleges consortium (with Ashton Sixth Form College, Holy Cross Catholic Sixth Form College, King George V Sixth Form College, Priestley College and Salford City College) that collaborates to save costs, gain efficiencies and learn from each other The college receives funding from: Education Funding Agency. -

Financial Statements

Financial Statements July 31 2016 The Manchester College (trading as LTE Group) July 31 Financial statements !"#$ FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2016 Key Management Personnel, Board of Governors and Professional advisers Key management personnel Key management personnel are defined as members of the Leadership Team and were represented by the following in 2015/16: John Thornhill, CEO; Accounting officer Lisa O’Loughlin, Principal Paul Taylor, Chief Operating Officer Peter Cox, Director Rob Cressey, Group Finance Director Carolyn Murphy, Director of Marketing (resigned August 2016) Ian Holborn, Managing Director, Work Based Learning / CFO (resigned June 2016) Board of Governors A full list of Governors is given on pages 14 of these financial statements. Mrs Jennifer Foote acted as Company Secretary to the Board of Governors throughout the period. Registered office: Openshaw Campus & Administration Centre Ashton Old Road Manchester M11 2WH Professional Advisers: Financial statement and reporting accountants: Grant Thornton UK LLP 4 Hardman Square Spinningfields Manchester M3 3EB Internal auditors: RSM Risk Assurance Services LLP 9th Floor 3 Hardman Street Manchester M3 3HF Bankers: National Westminster Bank Manchester City Centre Branch 11 Spring Gardens Manchester M2 1FB Solicitors: Mills & Reeve LLP 1 New York Street Manchester M1 4AD DWF LLP 1 Scott Place 2 Hardman Street Manchester M3 3HH 1 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 JULY 2016 CONTENTS Page number Strategic report 3 Statement of Corporate Governance and Internal Control .. .. .. 15 Governing Body’s statement on the College’s regularity, propriety and compliance with Funding body terms and conditions of funding .. .. 23 Statement of Responsibilities of the Members of the Corporation . -

Priestley College Alumni Association Offers You a Tailored Service

COLLEGE LEAVERinformationguide ? ACCESS PROFESSIONAL CAREERS ADVICE ALTERNATIVE PROVIDERS OF FURTHER EDUCATION, EMPLOYMENT & TRAINING YOUR OPTIONS ON LEAVING COLLEGE Leaving College can be one of the most exciting but also most overwhelming times in your life. In addition to this, the Covid-19 pandemic has also meant a new and uncertain time for everyone, so it is it may affect you in different ways. Many of you may have had a positive experience, including spending time with your families, felt less pressure form tests and exams from lockdown. However, some of you may have faced a range of difficulties. As lockdown restrictions are slowly lifted, it is only natural for there to be some anxiety about what comes next. You may be worried about your results, going to university and applying for jobs. You have gone suddenly from routine and timetables to having nothing planned at all. It’s natural to feel a little insecure about it all but don’t worry, life post-College really is the start of the most exciting chapter. Leaving Priestley does not mean that we forget about you, you are not alone. EXTERNAL SUPPORT AVAILABLE IF YOU ARE CONCERNED ABOUT YOUR GENERAL WELLBEING Feeling anxious or worried? Would like to talk to someone in confidence about a mental health issue you are experiencing? Confidential information and support are available. Wellbeing page on the Priestley website We have identified some key sources for you to help you with the current climate as well as any general concerns you may have. https://www.priestley.ac.uk/wellbeing-and- support/ Happy? OK? Sad? In addition, this is an excellent website which highlights support in the Warrington area as well as nationally, whether you or someone you know requires urgent or non-urgent help. -

North West Introduction the North West Has an Area of Around 14,100 Km2 and a Population of Almost 6.9 Million

North West Introduction The North West has an area of around 14,100 km2 and a population of almost 6.9 million. The metropolitan areas of Greater Manchester and Merseyside are the most significant centres of population; other major urban areas include Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 490 people per km2, making the North West the most densely populated region outside London. This population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region; Cumbria in the north has just 24 people per km2. The economy The economic output of the North West is almost £119 billion, which represents 13 per cent of the total UK gross value added (GVA), the third largest of the nine English regions. The region is very varied economically: most of its wealth is created in the heavily populated southern areas. The unemployment rate stood at 7.5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2010, compared with the UK rate of 7.9 per cent. The North West made the highest contribution to the UK’s manufacturing industry GVA, 13 per cent of the total in 2008. It was responsible for 39 per cent of the UK’s GVA from the manufacture of coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel, and 21 per cent of UK manufacture of chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres. It is also one of the main contributors to food products, beverages, tobacco and transport equipment manufacture. Gross disposable household income (GDHI) of North West residents was one of the lowest in the country, at £13,800 per head. -

Regional Profiles North-West 29 ● Cumbria Institute of the Arts Carlisle College__▲■✚ University of Northumbria at Newcastle (Carlisle Campus)

North-West Introduction The North-West has an area of around 14,000 km2 and a population of over 6.3 million. The metropolitan area of Greater Manchester is by far the most significant centre of population, with 2.5 million people in the city and its wider conurbation. Other major urban areas are Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 477 people per km2, making the North-West the most densely populated region outside London. However, the population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region. Cumbria, by contrast, has the third lowest population density of any English county. Economic development The economic output of the North-West is around £78 billion, which is 10 per cent of the total UK GDP. The region is very varied economically, with most of its wealth created in the heavily populated southern areas. Important manufacturing sectors for employment and wealth creation are chemicals, textiles and vehicle engineering. Unemployment in the region is 5.9 per cent, compared with the UK average of 5.4 per cent. There is considerable divergence in economic prosperity within the region. Cheshire has an above average GDP, while Merseyside ranks as one of the poorest areas in the UK. The total income of higher education institutions in the region is around £1,400 million per year. Higher education provision There are 15 higher education institutions in the North-West: eight universities and seven higher education colleges. An additional 42 further education colleges provide higher education courses. There are almost 177,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) students in higher education in the region. -

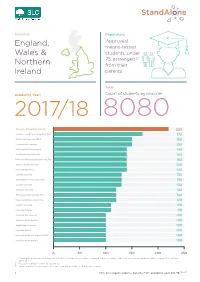

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Manchester Floor Plan Manchester Exhibitors 2020

MANCHESTER EXHIBITORS 2020 MANCHESTER University of Aberdeen 1 Cardiff Metropolitan University 33 University of Leicester 82 University of Southampton 135 University of Wolverhampton 148 HIGHER EDUCATION Abertay University 2 University of Central Lancashire 34 University of Lincoln 80 Solent University (Southampton) 136 University of Winchester 160 EXHIBITION Aberystwyth University 5 Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 95 University of Liverpool 88 University of St Andrews 137 University of Worcester 161 The Academy of Contemporary Music 3 University of Chester 35 Liverpool Hope University 79 SGS College 139 University of York 162 3 – 4 MARCH 2020 Anglia Ruskin University 4 City, University of London 121 Staffordshire University 138 83 163 Arden University 6 Coventry University 36 University of Stirling 140 Aston University 7 University for the Creative Arts 40 LMA 91 University of Strathclyde 142 Bangor University 9 University of Cumbria 39 London Metropolitan University 81 University of Suffolk 141 Supported by Barnsley College 8 De MontFort University 38 London School of Economics University of Sunderland 143 CAREER AND APPRENTICESHIP 97 and Political Science University of Bath 10 University of Surrey 144 British Army H 89 Loughborough University 84 Bath Spa University 11 University of Sussex 146 Microsoft C UCEN Manchester 92 University of Bedfordshire 12 Swansea University 149 National Apprenticeship Service A University of Derby 41 The University of Manchester 85 In association with Birmingham City University 14 Teesside University -

Members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) 2019-20

Members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) 2019-20 The following institutions are members of QAA for 2019-20. To find out more about QAA membership, visit www.qaa.ac.uk/membership List correct at time of publication – 18 June 2020 Aberystwyth University Activate Learning AECC University College Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education Amity Global Education Limited Anglia Ruskin University Anglo American Educational Services Ltd Arden University Limited Arts University Bournemouth Ashridge Askham Bryan College Assemblies of God Incorporated Aston University Aylesbury College Bangor University Barnsley College Bath College Bath Spa University Bellerbys Educational Services Ltd (Study Group) Bexhill College Birkbeck, University of London Birmingham City University Birmingham Metropolitan College Bishop Grosseteste University Blackburn College Blackpool and The Fylde College Bolton College Bournemouth University BPP University Limited Bradford College Brockenhurst College Buckinghamshire New University Burnley College Burton & South Derbyshire College 1 Bury College Cambridge Regional College Canterbury Christ Church University Cardiff and Vale College Cardiff Metropolitan University Cardiff University CEG UFP Ltd Central Bedfordshire College Cheshire College South and West Chichester College Group Christ the Redeemer College City College Plymouth City of Bristol College City, University of London Colchester Institute Coleg Cambria Cornwall College Coventry University Cranfield University David Game College De Montfort