Childhood, Region, and Iowa's Missing Paperboys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paperboys Workshops 092515

The Paperboys Workshops Celtic Fiddle Kalissa Landa teaches this hands-on workshop covering Irish, Scottish, Cape Breton and Ottawa Valley styles. The class covers bow technique, ornamentation, lilts, slurs, slides etc. and includes reels, jigs, polkas, airs and strathspeys. Kalissa has been playing fiddle since before she could walk, and dedicates much of her time to teaching both children and adults. She runs the fiddle program at the prestigious Vancouver Academy of Music. For beginners, intermediate, or advanced fiddlers. Celtic Flute/Whistle Paperboys flute/whistle player Geoffrey Kelly will have you playing a jig or a reel by the end of the class. While using the framework of the melody, you will learn many of the ornaments used in Celtic music, including slides, rolls, trills, hammers etc. We will also look at some minor melody variations, and where to use them in order to enhance the basic melody. Geoffrey is a founding member of Spirit of the West, a four-year member of the Irish Rovers, and the longest serving Paperboy. Geoffrey has composed many of the Paperboys’ instrumentals. Latin Music Overview In this workshop, the Paperboys demonstrate different styles of Latin Music, stopping to chat about them and break down their components. It's a Latin Music 101 for students to learn about the different kinds of genres throughout Latin America, including but not limited to Salsa, Merengue, Mexican Folk Music, Son Jarocho, Cumbia, Joropo, Norteña, Son Cubano, Samba, and Soca. This is more of a presentation/demonstration, and students don't need instruments. Latin Percussion Percussionist/Drummer Sam Esecson teaches this hands-on workshop, during which he breaks down the different kinds of percussion in Latin music. -

Port Orford Today! FREE! Serving the Port Orford Area Since 1990 Vol

Port Orford Today! FREE! Serving the Port Orford area since 1990 Vol. 11 Number 12 Thursday, March 23, 2000 © 2000 by The Downtown Fun Zone The Downtown Fun Zone Valerie: [email protected] Evan & Valerie Kramer, Owners Evan: ........... [email protected] 832 Highway 101, P.O. Box 49 Nancy: ... [email protected] This week is for the birds! Port Orford, OR 97465 Brenda: .. [email protected] Bazillions of Bird Houses Art Show (541) 332-6565 (Voice or FAX) http://www.harborside.com/~funzone The Woodpeckers music group Democrats Host Bradbury Bradbury opened his remarks by saying it Langlois and Bandon school districts. He said she is the first woman professor at By Evan Kramer was fun to be back in the saddle. Bradbury said it lights him up to be Sec- Southwestern Oregon Community Col- The Curry County Demo- retary of State and continued it was im- lege where she currently teaches account- cratic Central Committee portant for people to participate in gov- ing. hosted Secretary of State ernment. Bradbury previously served in Bradbury spoke about the need to recog- Bill Bradbury as their the state representative and state senator nize how our economy is changing from guest speaker at Saturday in this area. one which had been dependent on fish- night’s grassroots dinner ing, agriculture and timber. He said that at the fairgrounds. Bradbury explained the secretary of state’s responsibilities. One is he or she is success has been the biggest problem for Governor John Kitzhaber appointed the chief elections officer and has the job the cranberry growers. -

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

The Canmore Highland Games and the Canmore Ceilidh – at the Canmore MIKE HURLEY Was Elected the Highland Games at Canmore, Alberta on August 31-September 1

ISSUE 28 VOLUME 4 Proudly Serving Celts in North America Since 1991 MAY/JUNE 2019 Inside This Issue PHOTO: Creative Commons/Flickr CIARÁN CANNON (R) the Irish Minister of State at the Depart- ment of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Diaspora and International De- velopment, was in western Canada and Washington State for the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations this March. He met with Premier John Horgan (L) in Victoria while in British Columbia to discuss common priorities and bi-lateral cooperation. [Full coverage of the Minister’s visit pages 7, 18, 19] SHOCK and sorrow across Ireland and the U.K. following news of the tragic death of 29-year-old journalist Lyra McKee. She was killed by dissident republicans while covering a disturbance in the ARTWORK by Wendy Andrew Creggan area of Derry on the evening of Thursday, April 18. BELTANE – Rhiannon-the lover, dances the blossoms into being. The white horse maiden brings joy, [Read more on page 27] creativity and a lust for life...a time of love and celebration. Beltane or Beltaine is the Gaelic May Day festival. Most commonly it is held on May 1, or about halfway between the spring equinox and the summer solstice. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Irish the name for the festival day is Lá Bealtaine, in Scottish Gaelic Là Bealltainn, and in Manx Gaelic Laa Boaltinn/Boaldyn. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals—along with Samhain, Imbolc and Lughnasadh – and is similar to the Welsh Calan Mai. -

Dave Behrman

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Dave Behrman This article was written by Budd Bailey. It’s a given that playing football can take a toll on a person. Even so, Dave Behrman was particularly unlucky in this area. Not only was his promising career cut short by physical problems, but Behrman’s quality of life also suffered well past the time that the game was just a memory for him. David Wesley Behrman was born on November 9, 1941, in Dowagiac, Michigan. That’s a small town in the southwest corner of the state, located about 25 miles north of South Bend, Indiana, and 25 miles southeast of Benton Harbor, Michigan. Dowagiac’s biggest celebrity (literally and figuratively) might be Chris Taylor, the 412-pound wrestler who won a bronze medal for the United States at the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Dave’s father was Chauncey Orville Behrman, who was born in Volinia – just east of Dowagiac. Mother Freda was born in Sturgis – about an hour southeast of Volinia near the Indiana state line. Dave was an only child. Behrman stayed in Dowagiac through his childhood, and attended Dowagiac Union High School. That facility had only one other pro football player among its alumni. Vern Davis played three games at cornerback for the 1971 Philadelphia Eagles. Information about Dave’s time with the Chieftains is tough to find. We do know that Behrman was on his way to become something of a giant on the line, since he reportedly checked in at 280 1 Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com pounds at that stage of his life. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’S Fractured Europe Quartet

humanities Article Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet Hadas Elber-Aviram Department of English, The University of Notre Dame (USA) in England, London SW1Y 4HG, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Recent years have witnessed the emergence of a new strand of British fiction that grapples with the causes and consequences of the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Building on Kristian Shaw’s pioneering work in this new literary field, this article shifts the focus from literary fiction to science fiction. It analyzes Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe quartet— comprised of Europe in Autumn (pub. 2014), Europe at Midnight (pub. 2015), Europe in Winter (pub. 2016) and Europe at Dawn (pub. 2018)—as a case study in British science fiction’s response to the recent nationalistic turn in the UK. This article draws on a bespoke interview with Hutchinson and frames its discussion within a range of theories and studies, especially the European hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer. It argues that the Fractured Europe quartet deploys science fiction topoi to interrogate and criticize the recent rise of English nationalism. It further contends that the Fractured Europe books respond to this nationalistic turn by setting forth an estranged vision of Europe and offering alternative modalities of European identity through the mediation of photography and the redemptive possibilities of cooking. Keywords: speculative fiction; science fiction; utopia; post-utopia; dystopia; Brexit; England; Europe; Dave Hutchinson; Fractured Europe quartet Citation: Elber-Aviram, Hadas. 2021. Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit 1. Introduction Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet. -

Rescuing Ambition

Putting Ambition to Work It’s time to reach further and dream bigger for the glory of God. Rescuing Ambition Rescuing “This is not a self-help book that doesn’t really help; it’s a wake-up alarm to rouse the good gifts specifically placed within us by God for his own glory.” SCOTT THOMAS, Rescuing Director, Acts 29 Church Planting Network “You will find this book not only profitable but also hard to put down.” JERRY BRIDGES, author, The Pursuit of Holiness Ambition “Dave Harvey has delivered a compelling case for developing God-ward ambition in the lives of men and women alike. With self-effacing humor, Dave reveals how being wired for glory can either corrupt us or lead us to a divine agenda. Highly recommended!” CAROLYN MCCULLEY, author, Radical Womanhood and Did I Kiss Marriage Goodbye? “I hope every leader in the church today will read Rescuing Ambition.” ED STETZER, President, LifeWay Research “Whether you’re on Main Street or Wall Street, this book has something to say to you.” JOSH DECKARD, Former Assistant Press Secretary to President Bush “Those who want to live with high and glorious purpose for the Savior must read this book.” THABITI ANYABWILE, Senior Pastor, First Baptist Church of Grand Cay- man; author, What Is a Healthy Church Member? Harvey DAVE HARVEY (DMin, Westminster Theological Seminary) is responsible for church planting, church care, and international expansion for Sovereign Grace Ministries, having served on the leadership team since 1995. He is the author of When Sinners Say I Do and a contributor to Worldliness: Resisting the Seduction of a Fallen World. -

March 4, 2019 Gov. Kim Reynolds Iowa Capitol Speaker Linda

SUSTAINING MEMBERS March 4, 2019 Business Record, Des Moines Cedar Rapids Gazette Centerville Iowegian Cityview, Des Moines Gov. Kim Reynolds Community Publishing Co., Armstrong Iowa Capitol Des Moines Register Iowa Broadcasters Association Speaker Linda Upmeyer President Charles Schneider Iowa Cubs Iowa House Iowa Senate Iowa Newspaper Association Iowa Public Television KCCI-TV, Des Moines Chief Clerk Carmine Boal Secretary Charlie Smithson KCRG-TV, Cedar Rapids Iowa House Iowa Senate Meredith Corporation N’West Iowa REVIEW, Sheldon Greetings: Quad-City Times, Davenport Sioux City Journal Storm Lake Times I write to you on behalf of the Iowa Freedom of Information WHO-TV, Des Moines Council. We are an education and advocacy organization that Woodward Communications Inc., Dubuque Telegraph Herald, was established 40 years ago by leaders from across Iowa — Dyersville Commercial, Cascade business executives, representatives of broadcasting and Pioneer, Manchester Press, Mount publishing, attorneys, educators, librarians and open- Vernon-Lisbon Sun, Marion Times, Anamosa Journal-Eureka, Solon government advocates — to provide a shared voice on issues Economist, North Liberty Leader, affecting open government and government accountability. Linn News-Letter FIRST AMENDMENT MEMBERS There has been much discussion in Iowa in the past two American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa months about the criteria for journalists wanting media Ames Daily Tribune credentials to cover proceedings in person of the Iowa Senate, Associated Press, Iowa Bureau Iowa House and the governor’s press conferences. The Carroll Daily Times Herald Burlington Hawk Eye questions have arisen over the decision to deny Laura Belin Rob Davis, Des Moines credentials to cover the House from inside the chamber and David E. -

Everett Rock's Weekend Live Music List Friday May 2, 2014 Time Venue City Band Genre*

Everett Rock's Weekend Live Music List Friday May 2, 2014 Time Venue City Band Genre* 4:45 Columbia Winery Woodinville Carly Calbero Al I R F 6:00 Bake's Place Bellevue The Gotz Lowe Duo B CR 6:00 Beaumont Cellars Woodinville Jeremy Serwer A Am 6:00 Lake Trail Taproom Kenmore Andrew Norsworthy F 6:30 Matthews Estate Winery Woodinville Robin Landry A R P 6:30 The Repp! Snohomish ROD COOK B CR 6:30 Salud Whisky & Wine Bar Bothell Chuck Gay P R C 6:30 Village Wines Woodinville Robbie Christmas P R RB 6:30 Woodinville Wine Cellars Woodinville Larry Murante A F R 7:00 Eagles Kirkland The Ugly Cousin Brothers Am I 7:00 Grazie Ristorante Bothell Andre Thomas and Quiet Fire J L RB 7:00 The Living Room Lodge Bellevue Jen Haugland Re 7:00 The Mirkwood Arlington PREHUMANITY - Mixed Messages - Root Legion - Jester's Secret - Hedon R M 7:00 Port Gardner Bay Winery Everett Alyse Rise J 7:30 Conway Muse Conway Sabrina y Los Reyes Mx F 7:30 Fleet Reserve #170 Everett Alien Culture CR 7:30 Spar Tree Granite Falls Marlin James (solo) every Friday C 7:30 Third Place Books Lk Forest Pk Mark DuFresne Band B 8:00 The Hawthorne Snohomish The Pin Drops R 8:00 Kirkland Perf Ctr Kirkland Maria Doyle Kennedy Al F 8:00 Salmon Bay Eagles Ballard Blues County Sheriff B 8:00 Triplehorn Brewing Co. Woodinville Shelley & the Curves CR 8:00 VFW Hall Oak Harbor el Colonel & Doubleshot with Mary De La Fuente B A 8:00 Wild Vine Bistro Bothell Black Stone River R 8:30 Mel's Old Village Pub Lynnwood $cratch Daddy B 8:30 Norm's Place Everett Red House B RB Fk 8:30 Yuppie Tavern -

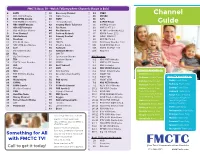

Channel Guide

FMCTC Basic TV - Watch TVEverywhere Channels Shown in Bold 2 ESPN 38 Discovery Channel 84 CNBC Channel 3 CBS KMTV-Omaha 39 WGN America 85 MSNBC 4 FOX KPTM-Omaha 40 HGTV 86 SyFy 5 FOX KDSM-Des Moines 41 History Channel 90 CSPAN-House Guide 6 NBC WOWT-Omaha 42 Country Music Television 91 CSPAN2-Senate 7 ABC KETV-Omaha 43 Fox News 93 KMTV LAFF 3.2 8 CBS KCCI-Des Moines 44 Fox Business 94 KPTM This-Omaha 42.2 9 Food Channel 45 Cartoon Network 95 KDSM Comet 17.2 10 USA Network 46 Comedy Central 96 WOWT COZI 6.2 11 Freeform 47 EWTN 98 KCCI MeTV 8.2 12 PBS KHIN-Iowa 48 FMCTV 100 WHO Iowa Weather 13.2 13 NBC WHO-Des Moines 49 Channel Guide 101 KXVO CHARGE 15.3 14 Golf 50 Hallmark 105 KDSM CHARGE 17.3 15 CW KXVO-Omaha 51 Hallmark Movies 108 KCCI 8.3 16 TLC 52 MAV TV 17 Big Ten Network 53 Sportsman Channel HD Channels 18 TBS 54 Outdoor Channel 3-1 CBS KMTV-Omaha 19 FMCTV Local Weather 55 RFDTV 3-2 KMTV LAFF-Omaha 23 VH1 56 Do It Yourself 3-3 KMTV Escape 24 TV Land 57 OWN 6-1 NBC WOWT-Omaha 25 MTC 58 BTN Overflow 6-2 WOWT COZI-Omaha Digital TV Available In: 26 PBS KYNE-Nebraska 59 Great American Country 6-3 WOWT H&I • Corley-Rural & Town 27 TNT 70 FX 6-4 WOWT ION • Defiance-Rural & Town Basic TV Available In: 28 Nickelodeon 71 FOX Sports 6-5 WOWT STAR • Earling-Rural & Town • Corley-Town Only 29 ESPN2 72 FXX 7-1 ABC KETV-Omaha • Defiance-Town Only 30 ESPN Classic 73 FX Movie Channel 7-2 KETV MeTV-Omaha • Hancock-Rural & Town 31 Weather Channel 74 FOX Sports 2 15-1 CW KXVO-Omaha • Harlan-Parts of Town, • Earling-Town Only 32 CNN 75 Olympic Channel -

The Lost Boys of Bird Island

Tafelberg To the lost boys of Bird Island – and to all voiceless children who have suffered abuse by those with power over them Foreword by Marianne Thamm Secrets, lies and cover-ups In January 2015, an investigative team consisting of South African and Belgian police swooped on the home of a 37-year-old computer engineer, William Beale, located in the popular Garden Route seaside town of Plettenberg Bay. The raid on Beale came after months of meticulous planning that was part of an intercontinental investigation into an online child sex and pornography ring. The investigation was code-named Operation Cloud 9. Beale was the first South African to be arrested. He was snagged as a direct result of the October 2014 arrest by members of the Antwerp Child Sexual Exploitation Team of a Belgian paedophile implicated in the ring. South African police, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Heila Niemand, cooperated with Belgian counterparts to expose the sinister network, which extended across South Africa and the globe. By July 2017, at least 40 suspects had been arrested, including a 64-year-old Johannesburg legal consultant and a twenty-year-old Johannesburg student. What police found on Beale’s computer was horrifying. There were thousands of images and videos of children, and even babies, being abused, tortured, raped and murdered. In November 2017, Beale pleaded guilty to around 19 000 counts of possession of child pornography and was sentenced to fifteen years in jail, the harshest punishment ever handed down in a South African court for the possession of child pornography.