Wallace & Gromit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

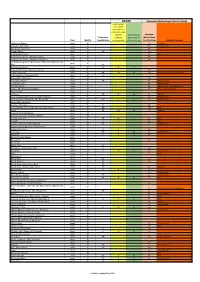

Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some Content May Not Be Appropriate for Children This Age

ACCM Kijkwijzer (Netherlands Classification) Some content may not be appropriate for children this age. Parental Content is age Kijkwijzer Australian guidance appropriate for (Netherlands Year Netflix Classification recommended children this age Classification) Kijkwijzer reasons 1 Chance 2 Dance 2014 N 12+ Violence 3 Ninjas: Kick Back 1994 N 6+ Violence; Fear 48 Christmas Wishes 2017 N All A 2nd Chance 2011 N PG All A Christmas Prince 2017 N 6+ Fear A Christmas Prince: The Royal Baby 2019 N All A Christmas Prince: The Royal Wedding 2018 N All A Christmas Special: Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug & Cat 2016 N Noir PG A Cinderella Story 2004 N PG 8 13 A Cinderella Story: Christmas Wish 2019 N All A Dog's Purpose 2017 N PG 10 13 12+ Fear; Drugs and/or alcohol abuse A Dogwalker's Christmas Tale 2015 N G A StoryBots Christmas 2017 N All A Truthful Mother 2019 N PG 6+ Violence; Fear A Witches' Ball 2017 N All Violence; Fear Airplane Mode 2020 N 16+ Violence; Sex; Coarse language Albion: The Enchanted Stallion 2016 N 9+ Fear; Coarse language Alex and Me 2018 N All Saints 2017 N PG 8 10 6+ Violence Alvin and the Chipmunks Meet the Wolfman 2000 N 6+ Violence; Fear Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip 2015 N PG 7 8 6+ Violence; Fear Amar Akbar Anthony 1977 N Angela's Christmas 2018 N G All Annabelle Hooper and the Ghosts of Nantucket 2016 N PG 12+ Fear Annie 2014 N PG 10 13 6+ Violence Antariksha Ke Rakhwale 2018 N April and the Extraordinary World 2015 N Are We Done Yet? 2007 N PG 8 11 6+ Fear Arrietty 2010 N G 6 9+ Fear Arthur 3 the War of Two -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

Shaun Le Mouton

STUDIOCANAL PRÉSENTE UNE PRODUCTION AARDMAN Un film réalisé par Richard Starzak et Mark Burton DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Durée : 1h25 Michèle ABITBOL-LASRY Sophie FRACCHIA Séverine LAJARRIGE 1, place du Spectacle SORTIE LE 1ER AVRIL 2015 184, boulevard Haussmann 92130 Issy-les-Moulineaux 75008 Paris Tél. : 01 71 35 11 19 Tél. : 01 45 62 45 62 [email protected] [email protected] / [email protected] Photos et dossier de presse sont disponibles sur www.studiocanal.fr Shaun est un petit mouton futé qui travaille, avec son troupeau, Comment survivre en ville quand on est un mouton ? Comment éviter pour un fermier myope à la ferme Mossy Bottom, sous l’autorité de d’être reconnu et donc échapper aux griffes acérées de Trumper le Bitzer, chien de berger dirigiste mais bienveillant et inefficace. La terrifiant responsable de la fourrière ? vie est belle, globalement, mais un matin, en se réveillant, Shaun Cette plongée urbaine sera pour le troupeau une course à 100 à se dit que sa vie n’est que contraintes. Il décide de prendre un l’heure, pleine d’aventures incroyables où Shaun va croiser la route jour de congé, avec pour cela un plan qui consiste à endormir le d’une petite chienne orpheline Slip, qui rêve d’avoir des parents fermier. Mais son stratagème fonctionne un peu trop bien et il perd et lui fera réaliser qu’il serait finalement bien plus heureux avec sa rapidement le contrôle de la situation. Une chose en entraînant une famille de moutons, à la ferme… autre, tout le troupeau se retrouve pour la première fois bien loin de la ferme et plus précisément : dans la grande ville. -

Film Is GREAT, Edition 2, November 2016

©Blenheim Palace ©Blenheim Brought to you by A guide for international media The filming of James Bond’s Spectre, Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire visitbritain.com/media Contents Film is GREAT …………………………………………………………........................................................................ 2 FILMED IN BRITAIN - British film through the decades ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 - Around the world in British film locations ……………………………………………….…………………........ 15 - Triple-take: Britain's busiest film locations …………………………………………………………………….... 18 - Places so beautiful you'd think they were CGI ……………………………………………………………….... 21 - Eight of the best: costume dramas shot in Britain ……………………………………………………….... 24 - Stay in a film set ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 27 - Bollywood Britain …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 30 - King Arthur's Britain: locations of legend ……………………………………………………………………...... 33 - A galaxy far, far away: Star Wars in Britain .…………………………………………………………………..... 37 ICONIC BRITISH CHARACTERS - Be James Bond for the day …………………………………………………………………………………………….... 39 - Live the Bridget Jones lifestyle ……………………………………………………………………………………..... 42 - Reign like King Arthur (or be one of his knights) ………………………………………………………….... 44 - A muggles' guide to Harry Potter's Britain ……………………………………………………………………... 46 FAMILY-FRIENDLY - Eight of the best: family films shot in Britain ………………………………………………………………….. 48 - Family film and TV experiences …………………….………………………………………………………………….. 51 WATCHING FILM IN BRITAIN - Ten of the best: quirky -

Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian Video Introduction to This Week's Film

April 28, 2020 (XL:13) Wes Anderson: ISLE OF DOGS (2018, 101m) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian video introduction to this week’s film (with occasional not-very-cooperative participation from their dog, Willow) Click here to find the film online. (UB students received instructions how to view the film through UB’s library services.) Videos: Wes Anderson and Frederick Wiseman in a fascinating Skype conversation about how they do their work (Zipporah Films, 21:18) The film was nominated for Oscars for Best Animated Feature and Best Original Score at the 2019 Academy Isle of Dogs Voice Actors and Characters (8:05) Awards. The making of Isle of Dogs (9:30) CAST Starting with The Royal Tenenbaums in 2001, Wes Isle of Dogs: Discover how the puppets were made Anderson has become a master of directing high- (4:31) profile ensemble casts. Isle of Dogs is no exception. Led by Bryan Cranston (of Breaking Bad fame, as Weather and Elements (3:18) well as Malcolm in the Middle and Seinfeld), voicing Chief, the cast, who have appeared in many Anderson DIRECTOR Wes Anderson films, includes: Oscar nominee Edward Norton WRITING Wes Anderson wrote the screenplay based (Primal Fear, 1996, American History X, 1998, Fight on a story he developed with Roman Coppola, Club, 1999, The Illusionist, 2006, Birdman, 2014); Kunichi Nomura, and Jason Schwartzman. Bob Balaban (Midnight Cowboy, 1969, Close PRODUCERS Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Encounters -

Animating Revolt and Revolting Animation

ChApter one Animating Revolt and Revolting Animation The chickens are revolting! —Mr. Tweedy in Chicken Run Animated films for children revel in the domain of failure. To captivate the child audience, an animated film cannot deal only in the realms of success and triumph and perfection. Childhood, as many queers in particular recall, is a long lesson in humility, awkwardness, limitation, and what Kathryn Bond Stockton has called “growing sideways.” Stockton proposes that childhood is an essentially queer experience in a society that acknowledges through its extensive training programs for children that hetero- sexuality is not born but made. If we were all already normative and heterosexual to begin with in our desires, orientations, and modes of being, then presumably we would not need such strict parental guidance to deliver us all to our common destinies of marriage, child rearing, and hetero- reproduction. If you believe that children need training, you assume and allow for the fact that they are always already anarchic and rebellious, out of order and out of time. Animated films nowadays succeed, I think, to the extent to which they are able to address the disorderly child, the child who sees his or her family and parents as the problem, the child who knows there is a bigger world out there beyond the family, if only he or she could reach it. Animated films are for children who believe that “things” (toys, nonhuman animals, rocks, sponges) are as lively as humans and who can Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/chapter-pdf/106945/9780822394358-002.pdf by TEMPLE UNIVERSITY user on 07 January 2019 1. -

Holidaytv © Seanlockephotography © | Seanlockephotography Dreamstime.Com

HolidayTV © Seanlockephotography © | Seanlockephotography Dreamstime.com An enduring tale The story of a little girl whose favorite toy comes to life and whisks her away to a magical doll kingdom has become a Christmas staple the world over. Two hundred years after its initial publication, it’s clear just how beloved “The Nutcracker” truly is. HolidayTV | The Nutcracker A timeless Christmas companion ‘The Nutcracker and the Mouse King’ celebrates its 200th anniversary By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media ore than 120 years ago, a ballet opened in St. Petersburg, just in time for MChristmas. It was not a success — it gleaned, in fact, much disparagement from critics — yet, with a production change here and a casting tweak there, “The Nutcracker” went on to become one of the most popular and well-known ballets in the world. One can’t begrudge composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky his part in the show’s eventual success, yet the bulk of it undoubtedly goes to the storyteller. The tale of a little girl whose favorite toy comes to life and whisks her away to a magical doll king- dom has become a Christmas staple. The ballet is just one of many productions spawned by the origi- nal novella written in 1816 by E. T. A. Hoffmann, and with 2016 marking the 200th anniversary of the story, it’s clear just how truly enduring it is. Hoffmann’s “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” has been adapted countless times for stage and screen. Details change here and there, but for the most part, they all follow the same basic structure, which sees little Marie (or Clara, as she’s called in the ballet) drawn into a dreamlike world where her toys come to life at Christmastime. -

EVGENI TOMOV Website: E-Mail

EVGENI TOMOV Website: http://evgenitomov.com e-mail: [email protected] Citizenship: Canadian Permanent resident status in the US (green card) QUALIFICATIONS A visual artist specialized in illustration, concept art, production design/art direction of feature animation films and TV animation series. EDUCATION 1980-86: A full time student and graduated with Master Degree in Fine Arts and Illustration from “Nikolai Pavlovitch” University, Sofia, Bulgaria. EMPLOYMENT Nov 2016 – present Senior Concept Illustrator at Marvel Studios on “Ant Man and the Wasp”, Burbank, CA Nov 2015 – Nov 2016 Visual development Artist & Designer at Reel FX, Santa Monica, CA March 2014 – October 2015 Independent visual development & concept artist, Art Director November 2014 – February 2015 Production Designer at LAIKA LLC, Portland, Oregon Worked on the development of the visual style and production design of a new animated feature. March 2014 – October 2014 Independent visual development & concept artist, Art Director September 2012 – February 2014 Visual development & concept artist at Dreamworks Animation, California, USA February 2012 – July 2012 Production Designer for the 3D feature animated film “The Little Prince”, Onyx Films, Paris, France October 2011 – Jan 2012 Visual development artist at Dreamworks Animation, Los Angeles, USA January 2008 – September 2011 Production Designer for the 3D feature animated film “Arthur Christmas”, an Aardman Animations/Sony Entertainment co-production. I was responsible for the visual concept of the film and the design style for characters, locations, props and lighting. I appointed and creatively managed the art department and the Art Directors. February 2005 – November 2008 Production Designer for the 3D feature animated film “The Tale of Despereaux”, a Universal Pictures project, London, UK. -

2D Animation Software You’Ll Ever Need

The 5 Types of Animation – A Beginner’s Guide What Is This Guide About? The purpose of this guide is to, well, guide you through the intricacies of becoming an animator. This guide is not about leaning how to animate, but only to breakdown the five different types (or genres) of animation available to you, and what you’ll need to start animating. Best software, best schools, and more. Styles covered: 1. Traditional animation 2. 2D Vector based animation 3. 3D computer animation 4. Motion graphics 5. Stop motion I hope that reading this will push you to take the first step in pursuing your dream of making animation. No more excuses. All you need to know is right here. Traditional Animator (2D, Cel, Hand Drawn) Traditional animation, sometimes referred to as cel animation, is one of the older forms of animation, in it the animator draws every frame to create the animation sequence. Just like they used to do in the old days of Disney. If you’ve ever had one of those flip-books when you were a kid, you’ll know what I mean. Sequential drawings screened quickly one after another create the illusion of movement. “There’s always room out there for the hand-drawn image. I personally like the imperfection of hand drawing as opposed to the slick look of computer animation.”Matt Groening About Traditional Animation In traditional animation, animators will draw images on a transparent piece of paper fitted on a peg using a colored pencil, one frame at the time. Animators will usually do test animations with very rough characters to see how many frames they would need to draw for the action to be properly perceived.