John C. Frémont Lithograph by John Henry Bufford, Boston, Massachusetts, 1856

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: the Administration of the Body and Blood of Jesus

religions Article Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: The Administration of the Body and Blood of Jesus James E. Faulconer Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Latter-day Saint (“Mormon”) liturgy opens its participants to a world undefined by a stark border between the transcendent and immanent, with an emphasis on embodiment and relationality. The formal rites of the temple, and in particular that part of the rite called “the endowment”, act as a frame that erases the immanent–transcendent border. Within that frame, the more informal liturgy of the weekly administration of the blood and body of Christ, known as “the sacrament”, transforms otherwise mundane acts of living into acts of worship that sanctify life as a whole. I take a phenomenological approach, hoping that doing so will deepen interpretations that a more textually based approach might miss. Drawing on the works of Robert Orsi, Edward S. Casey, Paul Moyaert, and Nicola King, I argue that the Latter-day Saint sacrament is not merely a ritualized sign of Christ’s sacrifice. Instead, through the sacrament, Christ perdures with its participants in an act of communal memorialization by which church members incarnate the coming of the divine community of love and fellow suffering. Participants inhabit a hermeneutically transformed world as covenant children born again into the family of God. Keywords: Mormon; Latter-day Saint; liturgy; rites; sacrament; endowment; temple; memory Citation: Faulconer, James E. 2021. Latter-Day Saint Liturgy: The In 1839, in contrast to most other early nineteenth-century American religious leaders, Administration of the Body and Joseph Smith, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints1 said, “Being Blood of Jesus. -

Lure of the Great Salt Lake

Lure of the Great Salt Lake January 2020 For DUP Lesson Leaders This photo array is reserved solely for use by a DUP Lesson Leader to supplement the appropriate lesson. No other uses are authorized and no images or content may be shared or distributed for any other purpose. Please feel free to use the images in any way you wish to enhance your lesson, including printed copies of the images to show your group as well as use in any digital presentations, as long as you adhere to the above restrictions. Please advise members of your group that they can order digital copies of any of the images provided here by contacting the DUP Photo Department. The funds generated by the DUP Photo Department help sustain our organization. Tel: 801-532-6479, Ext 206 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isdup.org Thank you for all you do. “Great Salt Lake – Moonrise from Fremont Island” painted by pioneer artist Alfred Lambourne. The painting is now located in Salt Lake City, at the Pioneer Memorial Museum, on the first floor, east wall. (DUP Collection) Jim Bridger (1804-1881). James Felix Bridger was an American mountain man, fur trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. (DUP Photo Collection) Albert Carrington (1813-1889. Carrington worked with Captain Howard Stansbury in 1849-50, surveying the Great Salt Lake. Carrington Island in the lake was named for him. (DUP Photo Collection) Current map of the Great Salt Lake showing locations of the islands and the average size of the Lake. -

Prepared in Cooperation with The

CONTINUOUS SEiailC-fcEFLECTION SURVEY OF THE GREAT SALT LAKE, UTAH EAST OF ANTELOPE AND FREMONT ISLANDS By Patrick M. Lairbert and John C. West U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 88-4157 Prepared in cooperation with the UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER RIGHTS Salt Lake City, Utah 1989 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, JR., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports Room 1016 Administration Building Federal Center, Bldg. 810 1745 West 1700 South Box 25425 Salt Lake City, Utah 84104 Denver, Colorado 80225 ii CONTENTS Page Abstract ........................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................... 1 Numbering system for wells in Utah ................................. 3 Geologic setting ................................................... 5 Seismic field survey ............................................... 8 Seismic interpretation ............................................. 9 Consolidated-rock surface ..................................... 10 Basin fill .................................................... 14 Summary and conclusions ............................................ 15 References cited ................................................... 16 ILLCJSTRATICNS Plate 1. Seismic-reflection profiles east of Antelope and Fremont Islands, -

North Platte Project, Wyoming and Nevraska

North Platte Project Robert Autobee Bureau of Reclamation 1996 Table of Contents The North Platte Project ........................................................2 Project Location.........................................................2 Historic Setting .........................................................4 Project Authorization.....................................................7 Construction History .....................................................8 Post-Construction History................................................20 Settlement of Project ....................................................26 Uses of Project Water ...................................................30 Conclusion............................................................32 Suggested Readings ...........................................................32 About the Author .............................................................32 Bibliography ................................................................33 Manuscript and Archival Collections .......................................33 Government Documents .................................................33 Articles...............................................................33 Newspapers ...........................................................34 Books ................................................................34 Other Sources..........................................................35 Index ......................................................................36 1 The North Platte Project -

Vol. 13, No. 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 1983

THE COCHISE '- Volume 13, Numbers 3 and 4 QUARTERLY Fall/Winter 1983 PHILIP ST. GEORGE COOK Table of Contents page The Mormon Battalion in Cochise County and Adjacent Areas 3 Photos: Cover photo of Colonel Philip St. George Cooke (from "The Mormon Battalion: Its History and Achievements" by B.H. Roberts, The Deseret News, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1919.) Monument near San Bernardino Ranch 18 Grave of Elisha Smith, near Paul Spur 29 Monument at entrance to Paul Spur road 30 Monument in Veterans Park, Douglas 33 Map of part of the march and wagon road of Lt. Colonel Cooke centerfold Edited tape of interview with Marvin L. Follett. 43 Larry D. Christiansen, a native of Utah, received both his Bachelor and Master's degrees from Utah State University. He also attended the University of Arizona and Wake Forest University. Christiansen served as the first editor of The Cochise Quarterly and has been a long-time member of the CCHAS. His interest in the Mormon Battalion and Cochise County history came with his moving to the area to teach at Cochise College. He has had one book published and several articles in magazines and quarterlies including The Cochise Quarterly. He now resides in North Carolina with his wife Becky and two children and pursues his hobbies of reading, writing and researching history, especially of the American West. * * * * Marvin L. FoUett, a long-time resident of Douglas, has studied, especially since the 1950s. the trail of the Mormon Battalion in Cochise County. His great-grandfather was William A. Follett, who was in Company B of the Mormon Battalion. -

Sandhill Cranes and the Platte River

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 1982 Sandhill Cranes and the Platte River Gary L. Krapu U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [email protected] Kenneth J. Reinecke U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Charles R. Frith U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Krapu, Gary L.; Reinecke, Kenneth J.; and Frith, Charles R., "Sandhill Cranes and the Platte River" (1982). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 87. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in TRANSACTIONS OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH NORTH AMERICAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL RESOURCES CONFERENCE (Washington, 1982) The Platte River Basin The Platte River Basin extends across about 90,000 square miles (233,100 km2) Gary L. Krapu, Kenneth J. Reinecke', and Charles R. Frith2 of Colorado, Wyoming, and Nebraska. The Platte begins near North Platte, Nebraska, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, at the confluence of the North and South Platte Rivers (Figure 1). The River loops Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, southeastward to form the Big Bend reach before crossing eastern Nebraska and Jarnestown, North Dakota joining the Missouri River near Omaha. The headwaters of the North Platte River are in north central Colorado, about 90 miles (145 km) northwest of Denver, and Introduction those of the South Platte about 60 miles (97 km) southwest of Denver (Figure 1). -

South Platte River, Littleton

South Platte River, Littleton FISH SURVEY AND MANAGEMENT DATA Paul Winkle, Aquatic Biologist, Denver [email protected] / 303-291-7232 General Information: The South Platte River, with its headwaters in South Park, flows out of Water- ton Canyon onto the plains of the Denver Metro area just upstream from Chatfield Reservoir. After exiting the reservoir, the river flows through the metro area and then northeast past Fort Morgan, Sterling, and other eastern Colorado towns before joining with the North Platte River in Nebraska to form the Platte River. There is excellent public access in the Littleton section, which is located within South Suburban Park. Location: Littleton, between C470 and Reynolds Landing, north of the Carson Nature Center. Fishery Management: Cold and warmwater angling. Annual Survey Data: (see page 2) Amenities and General Info. Previous Stocking Sportfishing Notes Approximately 2 1/2 miles of continuous public access 2019 Although this section of the within South Suburban Park Rainbow Trout South Platte River is stocked by way of cement walking/ with rainbow trout, several bike path 2018 species of fish escape through Parking available at the Rainbow Trout Chatfield dam into the river. junction of C470 and the These species include wall- South Platte River, and at 2017 eye, channel catfish, rainbow Carson Nature Center Rainbow Trout trout, and smallmouth bass Restrooms at the parking lot Smallmouth bass and brown at C470 and the South Platte 2016 trout sustain their river popu- River, and at Carson Nature Rainbow Trout lations through natural repro- Center duction 2015 A major fish habitat improve- Rainbow Trout ment project was completed Fishing Regulations here within the past several General regulations apply 2014 years, narrowing the channel Rainbow Trout to create deeper water. -

Great Salt Lake FAQ June 2013 Natural History Museum of Utah

Great Salt Lake FAQ June 2013 Natural History Museum of Utah What is the origin of the Great Salt Lake? o After the Lake Bonneville flood, the Great Basin gradually became warmer and drier. Lake Bonneville began to shrink due to increased evaporation. Today's Great Salt Lake is a large remnant of Lake Bonneville, and occupies the lowest depression in the Great Basin. Who discovered Great Salt Lake? o The Spanish missionary explorers Dominguez and Escalante learned of Great Salt Lake from the Native Americans in 1776, but they never actually saw it. The first white person known to have visited the lake was Jim Bridger in 1825. Other fur trappers, such as Etienne Provost, may have beaten Bridger to its shores, but there is no proof of this. The first scientific examination of the lake was undertaken in 1843 by John C. Fremont; this expedition included the legendary Kit Carson. A cross, carved into a rock near the summit of Fremont Island, reportedly by Carson, can still be seen today. Why is the Great Salt Lake salty? o Much of the salt now contained in the Great Salt Lake was originally in the water of Lake Bonneville. Even though Lake Bonneville was fairly fresh, it contained salt that concentrated as its water evaporated. A small amount of dissolved salts, leached from the soil and rocks, is deposited in Great Salt Lake every year by rivers that flow into the lake. About two million tons of dissolved salts enter the lake each year by this means. Where does the Great Salt Lake get its water, and where does the water go? o Great Salt Lake receives water from four main rivers and numerous small streams (66 percent), direct precipitation into the lake (31 percent), and from ground water (3 percent). -

Water Quality of the North Platte River, East-Central Wyoming

WATER QUALITY OF THE NORTH PLATTE RIVER, EAST-CENTRAL WYOMING By L. R. Larson U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 84-4172 Cheyenne, Wyoming 1985 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: Open-File Services Section District Chief Western Distribution Branch U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey 2120 Capitol Avenue Box 25425, Federal Center P.O. Box 1125 Denver, Colorado 80225 Cheyenne, Wyoming 82003 Telephone: (303) 236-7476 CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 3 Description of the problem 3 Purpose of the report 4 Scope of the investigation 4 Description of the streamflow and its relation to water quality 4 Concentrations or values and criteria for selected water-quality constituents or characteristics 12 Alkalinity 15 Arsenic 16 Barium 16 Bicarbonate 20 Boron 20 Cadmium 20 Calcium 24 Carbonate 24 Total organic carbon 26 Chemical oxygen demand 26 Chloride 30 Chromium 30 Fecal coliform bacteria 33 Copper--------------------------------------------------------------- 33 Di ssol ved sol i ds 35 Fluoride 35 Hardness 38 Hydrogen-ion activity 40 Iron 40 Lead 43 Magnesium 43 Manganese 46 Mercury 46 Ammonia nitrogen 49 Nitrate nitrogen 53 Total kjeldahl nitrogen- 56 Oxygen 56 Total phosphorus 59 Polychlorinated biphenyls 59 Potassium 61 Suspended sediment 61 Selenium 63 Silica 66 Sodi urn----- ------ .--- .... ... .............. .... ....... 66 Sodiurn-adsorption ratio 69 Specifie conductance 72 Stronti urn 72 Sulfate- 75 Turbidity 78 Zinc 79 Discussion and conclusions 82 References 85 - i i i - ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing study reach of the North Platte River and location of sampling stations 5 2. -

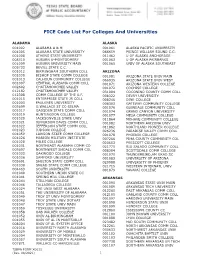

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Ramah, New Mexico, 1876-1900 an Historical Episode with Some Value Analysis'

RAMAH, NEW MEXICO, 1876-1900 AN HISTORICAL EPISODE WITH SOME VALUE ANALYSIS' BY IRVING TELLING* W'HE„ N BRIGHAM YOUNG planted colonies throughout the semi- arid intermountain region, the conditions under which settlers were called to live equalled in hardship those met anywhere on the American frontier. Yet the number of communities which failed was amazingly small. The Latter-day Saints remained at their posts through the most trying times.2 Why should these people leave their old homes to build anew, suffering again the trials of pioneering in an unfriendly country? Ramah was such a Mormon colony. In west central New Mexico, surrounded by a few hundred Navaho Indians, and twenty miles east of the Indian pueblo of Zuni, the settlement was founded as a mission to the Indians. A contemporary of the first Mormon settlements on the Little Colorado River (Sunset, Obed, Brigham City, and Joseph City), Ramah has been the only one of these initial ventures besides Joseph City to survive the struggle against a hostile environment.3 A mountain ridge *Mr. Telling recently received his doctor's degree from Harvard Uni versity, and is now serving as history instructor at the University of Massa chusetts. This study is an outgrowth of his thesis dealing with the social historyof the Gallup, New Mexico, area. 1The author is grateful for assistance in this study to Mrs. Wayne Clawson and E. Atheling Bond, of Ramah; Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Frederick Nielson, of Bluewater, New Mexico; A. William Lund, Stanley Ivins, Preston Nibley, William Mulder, and Professor Leland H. Creer, of Salt Lake City; Professors Clyde Klucknohn, Arthur M. -

Lehi Historic Archive File Categories Achievements of Lehi Citizens

Lehi Historic Archive File Categories Achievements of Lehi Citizens AdobeLehi Plant Airplane Flights in Lehi Alex ChristoffersonChampion Wrestler Alex Loveridge Home All About Food and Fuel/Sinclair Allred Park Alma Peterson Construction/Kent Peterson Alpine Fireplaces Alpine School BoardThomas Powers Alpine School District Alpine Soil/Water Conservation District Alpine Stake Alpine Stake Tabernacle Alpine, Utah American Dream Labs American Football LeagueDick Felt (Titans/Patriots) American Fork Canyon American Fork Canyon Flour Mill American Fork Canyon Mining District American Fork Canyon Power Plant American Fork Cooperative Institution American Fork Hospital American Fork, Utah American Fork, UtahMayors American Fork, UtahSteel Days American Legion/Veterans American Legion/VeteransBoys State American Patriotic League American Red Cross Ancient Order of United Workmen (AOUW) Ancient Utah Fossils and Rock Art Andrew Fjeld Animal Life of Utah Annie Oakley Antiquities Act Arcade Dance Hall Arches National Park Arctic Circle Ashley and Virlie Nelson Home (153 West 200 North) Assembly Hall Athenian Club Auctus Club Aunt Libby’s Dog Cemetery Austin Brothers Companies AuthorFred Hardy AuthorJohn Rockwell, Historian AuthorKay Cox AuthorLinda Bethers: Christmas Orange AuthorLinda JefferiesPoet AuthorReg Christensen AuthorRichard Van Wagoner Auto Repair Shop2005 North Railroad Street Azer Southwick Home 90 South Center B&K Auto Parts Bank of American Fork Bates Service Station Bathhouses in Utah Beal Meat Packing Plant Bear