Legal Studies | 2020 Chapter Showcase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Mow!,'Mum INN Nn

mow!,'mum INN nn %AUNE 20, 1981 $2.75 R1-047-8, a.cec-s_ Q.41.001, 414 i47,>0Z tet`44S;I:47q <r, 4.. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS COMMODORES.. -LADY (YOU BRING TUBES, -DON'T WANT TO WAIT ANY- POINTER SISTERS, "BLACK & ME UP)" (prod. by Carmichael - eMORE" (prod. by Foster) (writers: WHITE." Once again,thesisters group) (writers: King -Hudson - Tubes -Foster) .Pseudo/ rving multiple lead vocals combine witt- King)(Jobete/Commodores, Foster F-ees/Boone's Tunes, Richard Perry's extra -sensory sonc ASCAP) (3:54). Shimmering BMI) (3 50Fee Waybill and the selection and snappy production :c strings and a drying rhythm sec- ganc harness their craziness long create an LP that's several singles tionbackLionelRichie,Jr.'s enoughtocreate epic drama. deep for many formats. An instant vocal soul. From the upcoming An attrEcti.e piece for AOR-pop. favoriteforsummer'31. Plane' "In the Pocket" LP. Motown 1514. Capitol 5007. P-18 (E!A) (8.98). RONNIE MILSAI3, "(There's) NO GETTIN' SPLIT ENZ, "ONE STEP AHEAD" (prod. YOKO ONO, "SEASON OF GLASS." OVER ME"(prod.byMilsap- byTickle) \rvriter:Finn)(Enz. Released to radio on tape prior to Collins)(writers:Brasfield -Ald- BMI) (2 52. Thick keyboard tex- appearing on disc, Cno's extremel ridge) {Rick Hall, ASCAP) (3:15). turesbuttressNeilFinn'slight persona and specific references tc Milsap is in a pop groove with this tenor or tit's melodic track from her late husband John Lennon have 0irresistible uptempo ballad from the new "Vlaiata- LP. An air of alreadysparkedcontroversyanci hisforthcoming LP.Hissexy, mystery acids to the appeal for discussion that's bound to escaate confident vocal steals the show. -

Reo Speedwagon Reschedules Concert at Four Winds New Buffalo

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE REO SPEEDWAGON RESCHEDULES CONCERT AT FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO Concert moved to Friday, November 9 NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – January 24, 2018 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians’ Four Winds® Casinos announce the performance date for REO Speedwagon at Four Winds New Buffalo’s® Silver Creek® Event Center has changed to Friday, November 9, 2018 at 9 p.m. All tickets purchased for the concert originally scheduled for February 9 will be honored at the November 9 performance. Hotel and dinner packages are still available on the night of the concert. Tickets are on sale now exclusively through Ticketmaster®, www.ticketmaster.com, or by calling (800) 745-3000. Ticket prices for the show start at $75 plus applicable fees. Four Winds New Buffalo will be offering hotel and dinner packages along with tickets to REO Speedwagon. The Hard Rock option is available for $512 and includes two concert tickets, a one-night hotel stay on Friday, November 9 and a $50 gift card to Hard Rock Cafe® Four Winds. The Copper Rock option is available for $612 and includes two tickets to the performance, a one-night hotel stay on Friday, November 9 and a $150 gift card to Copper Rock Steak House®. All hotel and dinner packages must be purchased through Ticketmaster. Formed in 1967 at college in Champaign, IL, signed in 1971, and fronted by iconic vocalist Kevin Cronin since 1972, REO Speedwagon’s non-stop touring and recording jump-started the burgeoning rock movement in the Midwest. Platinum albums and radio staples soon followed, including the number one singles “Keep on Loving You” and “Can’t Fight This Feeling,” plus fan favorites like “Take It on the Run,” and “Ridin’ The Storm Out.” The band released its most successful album—Hi Infidelity—in 1980, which spent 15 weeks at #1 and has since earned the RIAA’s coveted 10X Diamond Award for surpassing 10 million units in the United States. -

ONE PARTICULAR NEWSLETTER the Ophicial Publication of the Orange County Parrot Head Club Partying with a Purpose for Over 20 Years!

ONE PARTICULAR NEWSLETTER The Ophicial Publication of the Orange County Parrot Head Club Partying with a purpose for over 20 years! www.ocphc.org December 2016 Last Mango in Irvine for Jimmy Buffett & The Coral Reefer Band Jimmy Buffett and The Coral Reefer Band played for the last time at The Irvine Meadows Amphitheater in Irvine on Saturday, October 22nd. The OCPHC was the national host for The Last Mango in Irvine Party. Word of the party went out on the club Facebook page and a pre-concert tailgate was planned near the event. Several club members joined the official Club RV to help prepare for the party. Much to our surprise, more than 10 additional RVs from all across the country joined us to get ready and gear up for the concert. Our old friend Jimmy Groovy showed up in costume and added to the pre-concert fun. Once inside the parking lot, Jerry Gontang played to the huge crowd In This Issue around the OCPHC event site. A.J.’s famous Cheeseburgers in Paradise were on the grill all were partying just like Bubba does in Pg 1: Last Mango in Irvine preparation for the concert. Once inside the venue, Jimmy and the CRB did not disappoint. The 26 song set included a tribute to Jimmy’s Pg 2: Andy’s Irvine Letter friend, Glenn Frey of The Eagles, who recently passed away. The show concluded in appropriate fashion with an acoustic version Pg 3: Tilleritaville of Lovely Cruise. Several club members related to the fact that they saw the first and last Buffett shows at Irvine Pg 4-7: Tales From MOTM Meadows. -

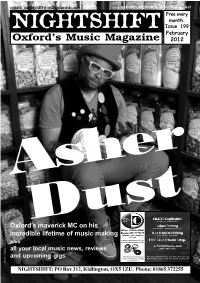

Issue 199.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 199 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2012 Asher Oxford’sDust maverick MC on his incredible lifetime of music making plus all your local music news, reviews and upcoming gigs. photo: Zahra Tehrani NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net TRUCK FESTIVAL is set to return this summer after founders Robin and Joe Bennett handed the event over to new management. Truck, which had been the centrepiece of Oxford’s live music calendar since 1998, surviving both floods and foot and mouth crises, succumbed to financial woes last year, going into administration in September. However, the event has been taken over by the organisers of Y-Not Festival in Derbyshire, which won Best Grassroots Festival 2011 at the UK Festival Awards. The new organisers hope to take Truck back to its roots as a local community festival. In a statement on the Truck website, Joe and Robin announced, ““We have always felt a great responsibility for the integrity and sustainability of Truck Festival, which grew so quickly and with such enthusiasm from very humble beginnings in 1998. Via Truck’s unique catering arrangements with the Rotary Club, tens of thousands of pounds have been raised for charities and good causes every year, including last year, and many great bands have taken their first steps to international prominence. BONNIE ‘PRINCE’ BILLY makes visits Oxford in May when he “However, after a notoriously difficult summer of trading for Truck teams up with alt.folk band Trembling Bells. -

Bluegrass Songs with Chords

The Freebird Fell Intro: C Am C Am I was just a teenage boy on my way to school Mama mad at me for me 'cause I turned on the news Details still uncertain as I put on my shoes Wasn't sure what happened but I knew I had the blues. F GC Cause that's the day the freebird fell Oh, I remember it well F GC So many cried when Ronnie died He never said farewell F G What he'd say in a southern song C Am Stories told still here long F GC The day the freebird fell. CAm Pulled myself together and I went on my way Missed the bus on purpose so I could walk that day Tuesday's Gone and Simple Man Play on in my mind Sweet Home Alabama, Curtis Loew and One More Time 'Cause that's the day the freebird fell Oh, I remember it well So many cried when Ronnie died He never said farewell What he'd say in a southern song Stories told still here long The day the freebird fell. Freebird fell Freebird fell, mmmm. Many years have come and gone, a lot of things have changed Father time has passed me by one thing stayed the same When I'm feeling lonely, when I'm feeling blue I crank up some of that good ol' honkey, Lord I think of you. Back to the day the freebird fell Oh, I remember it well So many cried when Ronnie died Visit www.traditionalmusic.co.uk for more songs. -

Booklist 3-4.Xlsx

2019 Years 3-4 Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Abela, Deborah The Stupendously Spectacular Spelling Bee 9781925324822 3-4, 5-6 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Agard, John Hello New! 978-1-84121-621-8 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan Please Mrs Butler 9780140314946 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan The Bravest Ever Bear 9780744578645 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan; Ingham, Bruce The Pencil 9781406309621 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan; Ingman, Bruce Previously 9781844280629 3-4 Ahlberg, Allan; Ingman, Bruce (ill.) Everybody Was a Baby Once 9781406321562 EC-2, 3-4 Airey, Miriam No Hat Brigade 978-1-74051-773-7 3-4 Alderson, Maggie Evangeline 9780670075355 EC-2, 3-4 Alexander, Goldie The Youngest Cameleer 978-1-74130-495-4 3-4, 5-6 Alexander, Goldie; Gaudion, Michele (ill.) Lame Duck Protest 978-1-921479-13-7 3-4 Allaby, Michael DK Guide to Weather 978-0-7513-2856-1 3-4 Allen, Emma; Blackwood, Freya (ill.) The Terrible Suitcase 9781862919402 EC-2, 3-4 Allen, Judy Anthology for the Earth 978-0-7636-0301-4 3-4 Allen, Scott Jesse the Elephant 9781921638138 3-4 Almond, David; Pinfold, Levi (ill.) The Dam 9781406304879 EC-2, 3-4 Almond, David; Smith, Alex T. The Tale of Angelino Brown 9781406358070 3-4, 5-6 Amadio, Nadine; Blackman, Charles (ill.) The New Adventures of Alice in Rainforest Land 978-0-949284-07-5 3-4 Andreae, Giles; Sharrat, Nick (ill.) Billy Bonkers series 3-4 Anholt, Laurence Camille and the Sunflowers 978-0-7112-1050-9 3-4 Anholt, Laurence Frida Kahlo and the Bravest Girl in the World 9781847806666 3-4 Anna Ciddor A Roman Day to Remember 978-0816767960 -

Robert Faurisson, Ecrits Re'visionnistes, Table of Contents

Ecrits Révisionnistes (1974-1998) translated from the French by S.Mundi By Robert Faurisson Table of Contents Historian Suffers Savage Beating Just who is Robert Faurisson? An Interview with the Author Chapters 1 through 4 Chapter 1: Against the Law Chapter 2: Nature of this Book Chapter 3: Historical Revisionism Chapter 4: The Official History Chapters 5 through 8 Chapter 5: Revisionism's Successes/Failures Chapter 6: Holocaust Propaganda Chapter 7: Gas Chambers Chapter 8: The Holocaust Witnesses Chapters 9 through 12 Chapter 9: Other Mystifications of WWII Chapter 10: A Universal Butchery Chapter 11: Who Wanted War? Chapter 12: Did the French Want War?Chapters 13 through 16 Chapter 13: Did Germans Want War? Chapter 14: British Masters of War Propaganda Chapter 15: British Intro Nazi Crime Shows Chapter 16: Americans & Soviets one-up British Chapters 17 through 20 Chapter 17: At Last a Fraud Denounced,1995 Chapter 18: Jewish Propaganda Chapter 19: Jews Impose a 'Creed of the Holocaust' Chapter 20: Historical Sciences Resist the Creed Chapters 21 through 24 Chapter 21: For a Revisionism with Gusto Chapter 22: A Conflict Without End Chapter 23: Future of Repression & the Internet Chapter 24: A Worsening Repression Chapter 25, Notes and References Chapter 25: The Duty of Resistance Notes and References Historian Suffers Savage Beating One of Europe's most prominent Holocaust revisionists, Dr. Robert Faurisson, was severely injured in a nearly fatal attack on September 16, 1989. After spraying a stinging gas into his face, temporarily blinding him, three Jewish assailants punched Dr. Faurisson to the ground and then repeatedly kicked him in the face and chest. -

MV Newsletter 3-06

Bama Breeze Jimmy’s latest CD is scheduled to be released on October 10. Award winning bassist Glenn Worf, Mobile native Will Kimbrough, Little Feats’ Billy Payne, and Party At The End Of The World slide guitar master Sonny Landreth joined Jimmy and the resident Coral Weather With You Reefers in Key West last February at what was then the Party At The End Of The World. We knew better than to refer to it as such so early, but it Everybody's On The Phone was a working title. In between fishing and boating trips, and sampling the Whoop De Doo keys culinary offerings, “should I spend time on the treadmill or eat at Hogfish,” Jimmy and his talented troop started the “party” that ended as Nothin' But A Breeze “weather” in Mac McAnally’s studio in Muscle Shoals. Cinco De Mayo In Memphis All the talent trapped in the old ice house on Key West’s historic waterfront Reggabilly Hill set the substance for the new recording, and the style was added by Mac and Mr. Utley. Meanwhile, Jimmy was overseas watching World Cup soccer and Elvis Presley Blues hanging with Mark Knopfler – not exactly dire straits. A video was filmed last Hula Girl At Heart summer for the song “Bama Breeze” and Jimmy told the Boston Globe’s Steve Morse, “It's a tribute to those honky-tonks that line the Gulf Coast where Wheel Inside The Wheel I grew up on the Alabama, Mississippi, Florida coast of the Gulf. It's about Silver Wings the infamous Flora-Bama bar. -

Taking Down Trumpism from Africa: Delegitimation, Not Collaboration, Please Patrick Bond 9 Feb 2017

Taking down Trumpism from Africa: Delegitimation, not collaboration, please Patrick Bond 9 Feb 2017 In the US there are already effective Trump boycotts seeking to delegitimise his political agenda. Internationally, protesters will be out wherever he goes. And from Africa, there are sound arguments to play a catalytic role, mainly because the most serious threat to humanity and environment is Trump’s climate change denialism. Consider two contrasting strategies to deal with the latest mutation of US imperialism: we should protest Donald Trump and Trumpism at every opportunity as a way to contribute to the unity of the world’s oppressed people, and now more urgently link our intersectional struggles; or we should somehow take advantage of his presidency to promote the interests of the ‘left’ or the ‘Global South’ where there is overlap in weakening Washington’s grip (such as in questioning exploitative world trading regimes). The latter position is now rare indeed, although before the election Hillary Clinton’s commitment to militaristic neoliberalism generated so much opposition that to some, the anticipated ‘paleo-conservatism’ of an isolationist-minded Trump appeared attractive. One international analyst of great reknown, Boris Kagarlitsky, makes this same argument this week largely because Trump is questioning pro-corporate ‘free trade’ deals. But the argument for selective cooperation with Trump was best articulated in Pambazuka as part of a series of otherwise compelling reflections by the Ugandan writer and former South Centre director Yash Tandon. Tandon might re-examine the ‘space’ he can ‘seize’ with Trump, the ‘fraud’ Since more than any other individual Tandon helped make the 1999 Seattle and Cancun World Trade Organisation summits a profound disaster for world elites, I take him very seriously. -

10 Reasons Why Congress Should Defund ICE's Deportation Force

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 1-1-2019 10 Reasons Why Congress Should Defund ICE’s Deportation Force Kari E. Hong Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Kari E. Hong. "10 Reasons Why Congress Should Defund ICE’s Deportation Force." NYU Review of Law & Social Change Harbinger 43, (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 10 REASONS WHY CONGRESS SHOULD DEFUND ICE’S DEPORTATION FORCE KARI HONG¥ Calls to abolish ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency tasked with deportations, are growing.1 ICE consists of two agencies – Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), which investigates transnational criminal matters, and Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO), which deports non-citizens. The calls to abolish ICE focus on the latter, the ERO deportation force. Defenders proffer that the idea is silly,2 that abolition could harm public safety,3 or that advocates of abolition must first explain what, if anything, would replace the agency.4 Those reasons are not persuasive. -

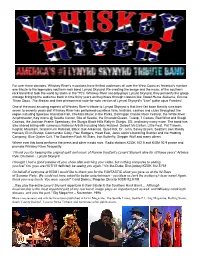

Since the Idea of Doing a Lynyrd Skynyrd Tribute Was Conceived By

For over three decades, Whiskey River’s musicians have thrilled audiences all over the West Coast as America's number one tribute to the legendary southern-rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd. Re-creating the image and the music of the southern rock band that took the world by storm in the "70's. Whiskey River not only plays Lynyrd Skynyrd, they personify the group onstage bringing the audience back in time thirty years as they blaze through classics like Sweet Home Alabama, Gimme Three Steps, The Breeze and their phenomenal note-for-note version of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s "Live" guitar opus Freebird. One of the most amazing aspects of Whiskey River’s tribute to Lynyrd Skynyrd is that their fan base literally runs from seven to seventy years old! Whiskey River has performed countless fairs, festivals, casinos and clubs throughout the region including Spokane Interstate Fair, Chehalis Music in the Parks, Darrington Classic Rock Festival, the White River Amphitheater, Key Arena @ Seattle Center, Bite of Seattle, the Emerald Queen, Tulalip, 7 Cedars, Red Wind and Skagit Casinos, the Jackson Prairie Speedway, the Sturgis Black Hills Rally in Sturgis, SD, and many many more. The band has also shared billing with numerous National Artists including Molly Hatchet, Delbert McClinton, Little Feat, Pat Travers, Foghat, Mountain, Grand Funk Railroad, Black Oak Arkansas, Quiet Riot, Dr. John, Savoy Brown, Seattle's own Randy Hansen, Elvin Bishop, Commander Cody, Paul Rodgers, Head East, Janis Joplin's band Big Brother and the Holding Company, Blue Oyster Cult, The Southern Rock All Stars, Iron Butterfly, Steppin Wolf and many others.