Training Methods in Distance Running

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2005 / 2006 the Racewalking Year in Review

2005 / 2006 THE RACEWALKING YEAR IN REVIEW COMPLETE VICTORIAN RESULTS MAJOR INTERNATIONAL RESULTS Tim Erickson 11 November 2006 1 2 Table of Contents AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITY GAMES, QLD, 27-29 SEPTEMBER 2005......................................................................5 VICTORIAN SCHOOLS U17 – U20 TRACK AND FIELD CHAMPIONSHIPS, SAT 8 OCTOBER 2005...................6 VRWC RACES, ALBERT PARK, SUNDAY 23 OCTOBER 2005...................................................................................7 CHINESE NATIONAL GAMES, NANJING, 17-22 OCTOBER 2005 ..........................................................................10 VICTORIAN ALL SCHOOLS U12-U16 CHAMPIONSHIPS, OLYMPIC PARK, 29 OCTOBER 2005 .....................12 VRWC RACES, ALBERT PARK, SUNDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2005.............................................................................13 PACIFIC SCHOOLS GAMES, MELBOURNE, NOVEMBER 2005..............................................................................16 AUSTRALIAN ALL SCHOOLS CHAMPS, SYDNEY, 8-11 DECEMBER 2005..........................................................19 VRWC RACES, SUNDAY 11 DECEMBER 2005...........................................................................................................23 RON CLARKE CLASSIC MEET, GEELONG, 5000M WALK FOR ELITE MEN, SAT 17 DECEMBER 2005.........26 GRAHAM BRIGGS MEMORIAL TRACK CLASSIC, HOBART, FRI 6 JANUARY 2006..........................................28 NSW 5000M TRACK WALK CHAMPIONSHIPS, SYDNEY, SAT 7 JANUARY 2006...............................................29 -

Finland in the Olympic Games Medals Won in the Olympics

Finland in the Olympic Games Medals won in the Olympics Medals by winter sport Medals by summer sport Sport Gold Silver Bronz Total e Sport Gol Silv Bron Total Athletics 48 35 31 114 d er ze Wrestling 26 28 29 83 Cross-country skiing 20 24 32 76 Gymnastics 8 5 12 25 Ski jumping 10 8 4 22 Canoeing 5 2 3 10 Speed skating 7 8 9 24 Shooting 4 7 10 21 Nordic combined 4 8 2 14 Rowing 3 1 3 7 Freestyle skiing 1 2 1 4 Boxing 2 1 11 14 Figure skating 1 1 0 2 Sailing 2 2 7 11 Biathlon 0 5 2 7 Archery 1 1 2 4 Weightlifting 1 0 2 3 Ice hockey 0 2 6 8 Modern pentathlon 0 1 4 5 Snowboarding 0 2 1 3 Alpine skiing 0 1 0 1 Swimming 0 1 3 4 Curling 0 1 0 1 Total* 100 84 116 300 Total* 43 62 57 162 Paavo Nurmi • Paavo Johannes Nurmi born in 13th June 1897 • Was a Finnish middle-long-distance runner. • Nurmi set 22 official world records at distance between 1500 metres and 20 kilometres • He won a total of nine gold and three silver medals in his twelve events in the Olympic Games. • 1924 Olympics, Paris Lasse Virén • Lasse Arttu Virén was born in 22th July 1949. • He is a Finnish former long-distance runner • Winner of four gold medals at the 1972 and 1976 Summer Olympics. • München 10 000m Turin Olympics 2006 Ice Hockey • In the winter Olymipcs year 2006 in Turin, the Finnish ice hockey team won Russia 4-0 in the semifinal. -

Paul Tergat O Most Observers It Came As No Great Surprise Tergat: Thank You Very That Paul Tergat Produced a WR 2:04:55 in Much

T&FN INTERVIEW Paul Tergat o most observers it came as no great surprise Tergat: Thank you very that Paul Tergat produced a WR 2:04:55 in much. I knew that I had T Berlin. So great are the talents of this legendary the potential. I knew that I by Sean Hartnett Kenyan—be it on the track, harrier course or the had the ability for bringing roads—that he faced WR expectations in every one down the World Record for of his previous five marathons. Tergat steadfastly the marathon, maybe by a maintained that “the marathon is a completely few seconds. But it was a big different event and I have much to learn.” surprise for me to go under This says much about the 34-year-old Kenyan, 2:05. Whatever you have whose quest for running greatness is matched by been putting in—in terms his passion for knowledge on all fronts. When he of energy, in terms of mental is not training his days are filled with a multitude preparedness and physical of family, business, and charitable activities, all torture—it is sweet when you the while juggling a couple of active cell phones. have such great moments. Conversation with Tergat ranges easily from world T&FN: Many people pre- issues to athletics or his homeland, and is always dicted that you would be the spiced with a bit of humor. WR holder right off the bat. But While Tergat is the epitome of a Kenyan distance the marathon is a very difficult runner, he is far from typical and did not even event, and you have made slow begin his running career until he completed his step-by-step progress. -

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Men's 10000M

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m by K Ken Nakamura Record to look for in Rio de Janeiro: 1) Last time KEN won gold at 10000m is back in 1968. Can Kamworor, Tanui or Karoki change that? 2) Can Mo Farah become sixth runner to win back to back gold? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:01.17 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 1 Beijing 2008 2 2 27:02.77 Sileshi Sihine ETH 2 Beijing 2008 3 3 27:04.11 Micah Kogo KEN 3 Beijing 2008 4 4 27:04.11 Moses Masai KEN 4 Beijing 2008 5 27:05.10 Kenenisa Bekele 1 Athinai 2004 6 5 27:05.11 Zersenay Tadese ERI 5 Beijing 2008 7 6 27:06.68 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 6 Beijing 2008 8 27:07.34 Haile Gebrselassie 1 Atlanta 1996 Slowest winning time since 1972: 27:47.54 by Alberto Cova (ITA) in 1984 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 47.8 29:59.6 Emil Zatopek TCH London 1948 18.68 27:47.54 Alberto Cova ITA Los Angeles 1984 Min 0.09 27:18.20 Haile Gebrselassie ETH Sydney 2000 Second line is largest margin since 1952 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 27:01.17 Kenenisa Bekele ETH Beijing 2008 2 27:02.77 Sileshi Sihine ETH Beijing 2008 3 27:04.11 Micah Kogo KEN Beijing 2008 4 27:04.11 Moses Masai KEN Beijing 2008 5 27:05.11 Zersenay Tadese ERI Beijing 2008 6 27:06.68 Haile Gebrselassie ETH Beijing 2008 7 27:08.25 Martin Mathathi KEN Beijing 2008 Multiple Gold Medalists: Kenenisa Bekele (ETH): 2004, 2008 Haile Gebrselassie (ETH): 1996, 2000 Lasse Viren (FIN): 1972, 1976 Emil -

List of International Competitions 2021

List of International Competitions 2021 This document constitutes the list of International Competitions at which the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) will conduct Testing in 2021 (sorted by the category of competition). The list will be published on the AIU and World Athletics’ websites and may be updated or amended from time to time to take account of changes to the 2021 competition calendar arising from the current global pandemic 1. It also serves as the definitive list of International Competitions for the purposes of determining whether an Athlete is an International-Level Athlete pursuant to Rule 1.4.4(b) of the 2021 World Athletics Anti-Doping Rules (2021 ADR)2. WORLD ATHLETICS SERIES 2021 MAY 01-02 World Athletics Relays Silesia, POL AUG 17-22 World Athletics U20 Championships Nairobi, KEN WORLD ATHLETICS INDOOR TOUR 2021 (GOLD) JAN 29 Indoor Meeting - Karlsruhe Karlsruhe, GER FEB 02 27. Banskobystrická latka - High Jump Men Banská Bystrica, SVK 09 Meeting Hauts-de-France Pas-de-Calais Liévin, FRA 13 New Balance Indoor Grand Prix Boston, USA 17 Copernicus Cup Torun, POL 24 Villa de Madrid Madrid, ESP WORLD ATHLETICS CROSS COUNTRY PERMITS 2021 FEB 02 44th Almond Blossom Cross Country Albufeira, POR San Giorgio su MAR 21 64°Campaccio-International Cross Country Legnano, ITA 28 89th Cinque Mulini San Vittore Olona, ITA TBC TBC Cross de Atapuerca TBC Burgos, ESP TBC TBC Cross Internacional de Soria TBC Soria, ESP TBC TBC Cross Internacional de la Constitucion TBC Alcobendas, ESP 1 This published list of International Competitions is without limitation to the AIU’s authority to conduct Testing at Competitions under Rule 5.1.3 2021 ADR. -

Office of Racing Integrity Harness Racing Stewards

OFFICE OF RACING INTEGRITY HARNESS RACING STEWARDS REPORT CLUB: LAUNCESTON PACING CLUB DATE: SUNDAY 16 APRIL 2017 TRACK: GOOD WEATHER: FINE STEWARDS: A CROWTHER (CHAIRMAN) R BROWN J ZUCAL S QUILL P HALL D COOPER J AINSCOW G GRIFFIN (STARTER) VETERINARY SURGEON: DR FIONA DUGGAN AND DR ALICIA FULLER Trainers with multiple runners engaged in any race were questioned as to their intended driving tactics. RACE 1 – ISLAND BLOCK AND PAVING PACE – 1680 METRES FEELIN DUSTY hung out severely in the score up and was significantly out of position at the start and will now be placed out of the draw, KRAFTY BOY has been placed back in the mobile draw. Shortly after the 300 metres, MISS SUPERBIA (Mark Yole) hung out under pressure, at the same time FEELIN DUSTY (Paul Hill) hung in under pressure and MISS SUPERBIA then contacted the sulky of FEELIN DUSTY and briefly raced rough. After unsuccessfully contesting the lead in the early stages, IDEN FOREST then restrained to take a trail. IDEN FOREST also hung in and contacted marker pegs. RACE 2 – LUXBET RACING CENTRE STAKES – 2200 METRES A Duggan was not listed in the racebook as the driver of THIRLSTANE KING. NEVER UNACHIEVABLE and ANIMI SUB IGNIS were both out of position at the start and will continue right out of the draw. THIRLSTANE KING was inconvenienced from the 500 metres behind the tiring ITSWHATILIKEABOUTU and was then held up in the latter stages of the race and unable to obtain clear running. TENFOUR was held up in the early part of the home straight. -

The Changing Role of Women in the Olympic Games

The changing role of women in the Olympic Games port belongs to all human beings. it is not surprising that women were ex- by Anita L. DeFrantz* It is unique to the human species. cluded from the first modern-era S Like humans, other animals engage Olympic Games, held in Athens in 1896. in play. But only the human species Games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, was Even though women were excluded takes part in sport. We are the only not in favour of women participating in from the 1896 Olympic Games, an en- ones on earth who set up barriers and the Games, or in sports in general. Writ- during legend has maintained that a try to jump over them to see who can ing in the Olympic Review in 1912: Cou- woman ran “unofficially” in the men’s get to the finish line first. We are the bertin defined the Games as “the solemn marathon. The evidence suggests that only ones who compete for the sheer and periodic exaltation of male athleti- no woman ran in the marathon along- satisfaction of winning. cism, with internationalism as a base, side the men, but that a woman did run Sport is our birthright. Sport provides loyalty as a means, art for its setting, the marathon course the day after the an opportunity for individuals to set and female applause as reward”. Ac- Olympic Games. their own goals and accomplish those cording to the sport historian Mary By the end of the nineteenth century goals, whether to run a mile in four min- Leigh, he believed that “a woman’s glory and during the beginning of the twenti- utes or to jump eight feet. -

Standard Tables 2020 E.S.A.A

Standard Tables 2020 E.S.A.A. National Standards are those performance levels for which standard badges may be purchased at the National Championships. Entry Standards are the minimum performance levels normally required for an athlete to be selected for a County Team for the National Championships. County Standards correspond to a good standard of performance by an athlete competing in a County Championship meeting. District Standard corresponds to a good standard of performance by an athlete competing at a District Championship meeting. These may need amendment to suit the variations in type of District Championship staged. School Standard corresponds to a good standard of performance by an athlete competing at a School Championship meeting. Except for Year 7 and 8 tables - the age groups, events and event specifications are as set out in the Track and Field Competition Rules. Years 7 and 8 The variety of events and specifications is offered in order to cater for the intense athletic interest and for the rapid physical changes which take place at this stage. It is stressed that success in the initial teaching of athletics stems from the understanding that the physical challenge to the pupil should not exceed that which can be comfortably handled. All children, therefore, should be started with light implements and low hurdles, and be allowed to progress as appropriate to themselves. This will almost certainly create some problems of organisation at school level, but these are NOT insurmountable. The Standards shown for younger age groups and for School and District level are being re-worked to match the Awards Scheme. -

Racing Stewards' Report

RACING STEWARDS’ REPORT – SATURDAY 20 JULY 2019 Board of Racing Stewards: Messrs S de Chalain (Chairman), B Daruty de Grandpré, G Kishtoo & Ms J Keevy. Weather: Fine Track: Races 1-5: Soft 2.9; Races 6-9: Good 2.8 Rail position: 2.50m RACE 1 – THE MTC WELCOMES THE INDIAN OCEAN GAMES 2019 CUP – 1500M Silver Rock – Fractious in its gate prior to the start being effected, then jumped awkwardly and was slow to begin. Approaching the 600 metres raced tight on the inside of Got To Fly and brushed the running rail. League Of Legends – Stood flat-footed, losing considerable ground. Never Fear – When urged forward after the start, shifted out and brushed Got To Fly . Inconvenienced near the 100 metres. He’s Got Gears – Raced wide in the early stages. Near the 1100 metres was eased to secure a position one off the rail. Passing the 400 metres was taken out from behind Got To Fly to improve its position. Shifted ground inwards in the home straight. Radlet – From its wide draw was taken across to race behind runners. Taken out to improve from the 350 metres and raced wide into the home straight. Social Network – Slow into stride. Blunderbuss – Slow to begin and, when being urged forward, failed to muster speed. Approaching the 600 metres raced momentarily tight on the inside of Got To Fly and brushed the running rail. Eased off the heels of Got To Fly approaching the 300 metres. Got To Fly – Approaching the 600 metres had to be eased when awkwardly placed close to the heels of Blazing Heart , which had shifted ground when insufficiently clear. -

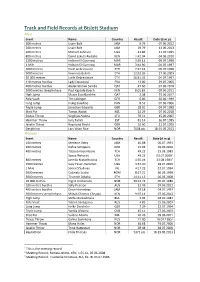

Track and Field Records at Bislett Stadium

Track and Field Records at Bislett Stadium Men Event Name Country Result Date (d.m.y) 100 metres Usain Bolt JAM 9.79 07.06.2012 200 metres Usain Bolt JAM 19.79 13.06.2013 400 metres Michael Johnson USA 43.86 21.07.1995 800 metres David Lekuta Rudisha KEN 1:42.04 04.06.2010 1500 metres Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3:29.12 09.07.1998 1 Mile Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3:44.90 04.07.1997 3000 metres Haile Gebrselassie ETH 7:27.42 09.07.1998 5000 metres Kenenisa Bekele ETH 12:52.26 27.06.2003 10 000 metres Haile Gebreslassie ETH 26:31.32 04.07.1997 110 metres hurdles Ladji Doucouré FRA 13.00 29.07.2005 400 metres hurdles Abderrahman Samba QAT 47.60 07.06.2018 3000 metres steeplechase Paul Kipsiele Koech KEN 8:01.83 09.06.2011 High Jump Mutaz Essa Barshim QAT 2.38 15.06.2017 Pole Vault Tim Lobinger GER 6.00 30.06.1999 Long Jump Irving Saladino PAN 8.53 02.06.2006 Triple Jump Jonathan Edwards GBR 18.01 09.07.1998 Shot Put Tomas Walsh NZL 22.29 07.06.2018 Discus Throw Virgilijus Alekna LTU 70.51 15.06.2007 Hammer Throw Jurij Tamm EST 81.14 16.07.1985 Javelin Throw Raymond Hecht GER 92.60 21.07.1995 Decathlon Lars Vikan Rise NOR 7608 pts 18-19.05.2013 Women Event Name Country Result Date (d.m.y) 100 metres Merlene Ottey JAM 10.88 06.07.1991 200 metres Dafne Schippers NED 21.93 09.06.2016 400 metres Tatjana Kocembova TCH 49.23 23.08.1983 Sanya Richards USA 49.23 03.07.20091 800 metres Jarmila Kratochvilova TCH 1:55.04 23.08.19832 1500 metres Suzy Favor-Hamilton USA 3:57.40 28.07.2000 1 Mile Sonia O'Sullivan IRL 4:17.25 22.07.1994 3000 metres Gabriela Szabo -

Model Function of Women's 1500M World Record Improvement Over Time

Undergraduate Journal of Mathematical Modeling: One + Two Volume 8 | 2018 Spring 2018 Article 3 2018 Model Function of Women’s 1500m World Record Improvement over Time Annie Allmark University of South Florida Advisors: Arcadii Grinshpan, Mathematics and Statistics Waren Bye, USF Athletics Department, Track and Field Head Coach Problem Suggested By: Annie Allmark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/ujmm Part of the Mathematics Commons UJMM is an open access journal, free to authors and readers, and relies on your support: Donate Now Recommended Citation Allmark, Annie (2018) "Model Function of Women’s 1500m World Record Improvement over Time," Undergraduate Journal of Mathematical Modeling: One + Two: Vol. 8: Iss. 2, Article 3. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5038/2326-3652.8.2.4890 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/ujmm/vol8/iss2/3 Model Function of Women’s 1500m World Record Improvement over Time Abstract We give an example of simple modeling of the known sport results that can be used for athletes’ self- improvement and estimation of future achievements. This project compares the women’s 1500-meter world record times to the time elapsed between when they were run. The function of time which describes this comparison is found through graphing the data and interpreting the graphs. Then the obtained model function is compared to the real time data. The conclusions drawn from the result include that the calculated function of time lacks in accuracy as time elapsed increases, but the model could be used to estimate the future world records. Keywords track and field, running, exponential modeling, line of best fit Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. -

Athletics SA 2021 State Track and Field Championships

Athletics SA 2021 State Track and Field Championships Final Timetable - as at 25/2/2021 Friday - 26th February Day Time Event Age Group Round Long Jump Triple Jump High Jump Pole Vault Shot Put Discus Javelin Hammer Fri 6.30 PM 3000 metres Walk Under 14 Men & Women FINAL 6.30 PM U17/18/20 Women Fri 3000 metres Walk Under 15 Men & Women FINAL Fri 3000 metres Walk Under 16 Men & Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 17 Men & Women FINAL 6.35 PM U17/18/20 Women Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 18 Men & Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 20 Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under Open Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 20 Men FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under Open Men FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Over 35 & Over 50 Men & FINAL 6.40 PM Women U14/15/16 Men Fri 6.45 PM 6.45 PM U15/16/U20 Women Fri 6.50 PM 6.50 PM Fri 6.55 PM 6.55 PM Fri 7.00 PM 200 metres Hurdles Under 15 Women FINAL 7.00 PM Fri 200 metres Hurdles Under 16 Women FINAL Fri 7.05 PM 200 metres Hurdles Under 15 Men FINAL 7.05 PM Fri 200 metres Hurdles Under 16 Men FINAL Fri 7.10 PM 200 metres Hurdles Over 35 & Over 50 Men & FINAL 7.10 PM Women Fri 7.15 PM 7.15 PM O35/O50 Women Fri 7.20 PM 400 metres Hurdles Open Men FINAL 7.20 PM Fri 400 metres Hurdles Under 20 Men FINAL 7.25 PM Fri 7:30 PM 400 metres Hurdles Under 17 Men FINAL 7.30 PM Fri 400 metres Hurdles Under 18 Men FINAL Fri 7.35 PM 7.35 PM Open Women Fri 7:40 PM 400 metres Hurdles Under 17 Women FINAL 7.40 PM Seated Fri 400 metres Hurdles Under 18 Women FINAL 7.45 PM U17/18/20 Men U17/18/20 Men Fri 7.50 PM 800 metres Open Men