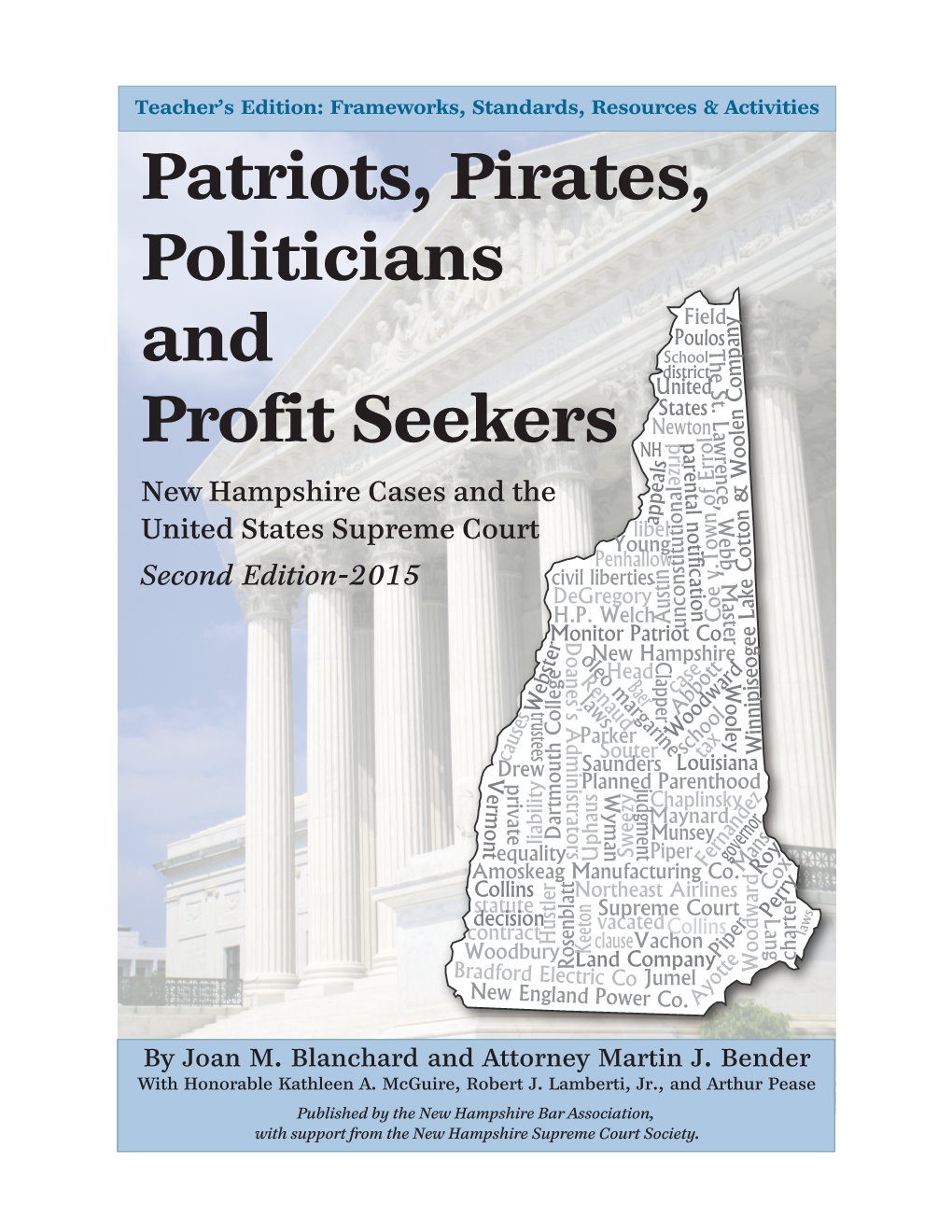

Patriots, Pirates, Politicians and Profit Seekers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A House Divided: When State and Lower Federal Courts Disagree on Federal Constitutional Rights

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications 11-2014 A House Divided: When State and Lower Federal Courts Disagree on Federal Constitutional Rights Wayne A. Logan Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Wayne A. Logan, A House Divided: When State and Lower Federal Courts Disagree on Federal Constitutional Rights, 90 NOTRE DAME L. REV. 235 (2014), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/161 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\90-1\NDL106.txt unknown Seq: 1 8-DEC-14 14:43 A HOUSE DIVIDED: WHEN STATE AND LOWER FEDERAL COURTS DISAGREE ON FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS Wayne A. Logan* “The operation of a double system of conflicting laws in the same state is plainly hostile to the reign of law. Janus was not a god of justice.”1 Despite our many differences, “We the People”2 take as a given that rights contained in our Federal Constitution will apply with equal force throughout the land. As John Jay put it in The Federalist No. 22, “we have uniformly been one people; each individual citizen everywhere enjoying the same national rights, privileges, and protection.”3 To better ensure federal rights uniformity, the Framers included the Supremacy Clause in the Consti- tution4 and ordained that there be “one supreme Court”5 to harmonize what Justice Joseph Story termed “jarring and discordant judgments”6 of lower courts, giving rise to “public mischiefs.”7 © 2014 Wayne A. -

Marblehead Boaters Slip Into Winter

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2016 Peabody gins up case for 20 more liquor licenses By Adam Swift areas in surrounding communities like Thursday night. If the committee ap- If the latest home rule petition gets ap- ITEM CITY EDITOR Salem, Beverly and Danvers, and unless proves the request, it will be forwarded to proved, Gravel said he hopes it is with there are liquor licenses, we won’t get the the Committee of the Whole for approval. more leeway than the 2014 license in- PEABODY — A home rule petition caliber of restaurants that will be able to At that point, Bettencourt would be able crease. led with the state legislature to allow survive.” to le a home rule petition with the state “On Main Street and Walnut Street, as many as 20 new liquor licenses in the In August, Mayor Edward A. Betten- legislature. there are a lot of buildings with poten- city could help open up downtown devel- court Jr. submitted a request to the In 2014, similar legislation added 10 li- tial for restaurants if they had a liquor opment, said a city councilor. council for approval of a home rule pe- quor licenses, bringing the city’s total to license,” he said. “I’m supportive of any move that will tition to increase the number of all-al- 11 beer and wine licenses and 70 all-alco- Gravel said there are already examples give us the ability to lock up restaurants cohol liquor licenses in Peabody by no hol licenses. But the 2014 legislation did on Main Street of how liquor licenses and other businesses that are looking at more than 20. -

Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate

DePaul Law Review Volume 23 Issue 2 Winter 1974 Article 5 Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate Luis Kutner Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Luis Kutner, Advice and Dissent: Due Process of the Senate, 23 DePaul L. Rev. 658 (1974) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol23/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVICE AND DISSENT: DUE PROCESS OF THE SENATE Luis Kutner* The Watergate affair demonstrates the need for a general resurgence of the Senate's proper role in the appointive process. In order to understand the true nature and functioning of this theoretical check on the exercise of unlimited Executive appointment power, the author proceeds through an analysis of the Senate confirmation process. Through a concurrent study of the Senate's constitutionally prescribed function of advice and consent and the historicalprecedent for Senatorial scrutiny in the appointive process, the author graphically describes the scope of this Senatorialpower. Further, the author attempts to place the exercise of the power in perspective, sug- gesting that it is relative to the nature of the position sought, and to the na- ture of the branch of government to be served. In arguing for stricter scrutiny, the author places the Senatorial responsibility for confirmation of Executive appointments on a continuum-the presumption in favor of Ex- ecutive choice is greater when the appointment involves the Executive branch, to be reduced proportionally when the position is either quasi-legis- lative or judicial. -

2013 Annual Report M Ission

2013 ANNUAL REPORT M ISSION The New England Council is an alliance of businesses, academic and health institutions, and public and private organizations throughout New England formed to promote economic growth and a high quality of life in the New England region. The New England Council is a leading voice on the issues that shape the region’s economy and quality of life. The Council focuses on key industries that drive the region’s economic growth including education, energy, transportation, technology and innovation, healthcare and financial services. THE NEW ENGLAND COUNCIL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2013 4 President’s Letter 5 Chairman’s Letter ADVOCACY & INITIATIVES 6 Overview 7 Advanced Manufacturing 8 Defense 9 Energy & Environment 11 Financial Services 12 Healthcare 14 Higher Education 16 New England Economic Partnership 17 Technology 19 Transportation Committee EVENTS 20 Annual Spring Event 22 Annual Dinner 24 Congressional Roundtable Series 26 Capital Conversations Series 28 Featured Events 30 Politics & Eggs Series ABOUT THE COUNCIL 31 DC Dialogue 32 Board of Directors 35 Members 3 THE NEW ENGLAND COUNCIL 2013 PRESIDENT’S LETTER DeaR NEW ENGland Council MEMBER: As I look back at 2013, I am once again impressed by what a successful and productive year it has been for The New England Council. That success has come on several fronts, from membership growth, to new programming and events, to effective advocacy for issues and policies that impact our region. I’m pleased to report that 2013 was an incredibly busy year for the Council with over 50 events and programs for our members over the course of the year. -

From the Winnipeg Tribune

THE WINNJPEU TRIBUNE, SATURDAY, MAY U, 1U14 2 Ml'Slj AND DRAMA M rsrc A NO BRAVA 1— , , -- —■---- 1 ■ —— - - M«el Evelyn Thaw Declares My Little Boy’s Sake)> '(Dt>y/7ojfre?r mation of pasts, and I can't f*e! that up. If 1 did I wouldn't deserve II. And ♦ + ♦ ♦ + + + + ♦ + + + + * phele of the opera house Is very large from another viewpoint. Anyway the "Hiram Perkins," and by Miss Rlancht ly the atmosphere of the halfpenny presentation is not devoid of interest. Chapman, whose long experience in ERE is a personal story It matters so much whether, si. years it's unfair to say that 1 am capitalis + • * • i haracter roles imminently fitted her ago. she was a martyr or a mummer. ing my personal notoriety. If I luid AMUSEMENTS FOR novelette. Mr. Laurence Irving has quite cap for the stage duties of his most cap with one of the most cared to do that 1 could have earned NEXT WEEK Now, why Is this? What is there In tured the esteem of the theatre-goers able wife, who would do honor to His Gone Too Far. AS ADVERTISED. human nature which compels men to of western Canada, if one may Judge pn olent's chair In any branch of th« talked of women in the $7,500 In one week, after the second modern suffrage movement among a n e p t gladly at one moment what by the enthusiasm with which he lias world--~Evelyn Nesbit Thaw. "1 know tti.it some persons arc paid Thaw trial, Jusl to stand up and he | been greeted every where upon his tour women. -

2015 Annual Report Swanzey, New Hampshire

2015 Annual Report Swanzey, New Hampshire The Four Seasons of Swanzey County, State & Federal Government Resources Contact and Meeting Information Governor Maggie Hassan Cheshire County - Commissioners Office of the Governor County Administrative Offices www.town.swanzey.nh.us State House 33 West Street Town Hall Contact Information Regular Monthly Meetings 107 North Main Street Keene, NH 03431 All meetings are held at Town Hall, unless Concord, NH 03301 352-8215 District 1 (Swanzey): 620 Old Homestead Highway otherwise posted. 207-2121 Peter Graves, Clerk PO Box 10009 Swanzey, New Hampshire 03446-0009 Consult the town calendar at New Hampshire General Court District 2: www.town.swanzey.nh.us for the most Chuck Weed, Vice Chair (603)352-7411 up-to-date meeting information. Senator Molly Kelly PO Box 267 District 3: NH Relay TDD 1(800)735-2964 Board of Selectmen Harrisville, NH 03450 cell: Stillman Rogers, Chair (603)352-6250 (Fax) Tuesday Evenings, 6 p.m. 603-491-2502 [email protected] x101 Town Clerk Deborah J. Davis: 352-4435 (home) NH Congressional Delegation x105 Code Enforcement Offi cer W. William Hutwelker III: 313-3948 (cell) Representative Jim McConnell U.S. Senators x107 Town Administrator Kenneth P. Colby Jr.: 357-3499 (home) PO Box G Senator Kelly Ayotte x108 Town Planner [email protected] Keene, NH 03431 41 Hooksett Road, Unit 2 x109 Tax Collector 357-7150 x110 General Assistance Coordinator Planning Board Manchester, NH 03104 2nd & 4th Thursday, 6 p.m. [email protected] x111 Finance Offi ce 622-7979 http://ayotte.senate.gov/ x114 Assessing Coordinator Zoning Board of Adjustment Representative Benjamin Tilton 3rd Monday (Except Jan & Feb), 7 p.m. -

University of Minnesota

THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Announces Its ;Uafclt eommellcemellt 1961 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 16 AT EIGHT-THIRTY O'CLOCK Univcrsitp uf Minncsuta THE BOARD OF REGENTS Dr. O. Meredith Wilson, President Mr. Laurence R. Lunden, Secretary Mr. Clinton T. Johnson, Treasurer Mr. Sterling B. Garrison, Assistant Sccretary The Honorable Ray J. Quinlivan, St. Cloud First Vice President and Chairman The Honorable Charles W. Mayo, M.D., Rochester Second Vice President The Honorable James F. Bell, Minneapolis The Honorable Edward B. Cosgrove, Le Sueur The Honorable Daniel C. Gainey, Owatonna The Honorable Richard 1. Griggs, Duluth The Honorable Robert E. Hess, White Bear Lake The Honorable Marjorie J. Howard (Mrs. C. Edward), Excelsior The Honorable A. I. Johnson, Benson The Honorable Lester A. Malkerson, Minneapolis The Honorable A. J. Olson, Renville The Honorable Herman F. Skyberg, Fisher As a courtesy to those attending functions, and out of respect for the character of the building, be it resolved by the Board of Regents that there be printed in the programs of all functions held in Cyrus Northrop Memorial Auditorium a request that smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms, and that members of the audience be not allowed to use cameras in the Auditorium. r/tis Js VOUf UnivcfsilU CHARTERED in February, 1851, by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Minnesota, the University of Minnesota this year celebrated its one hundred and tenth birthday. As from its very beginning, the University is dedicated to the task of training the youth of today, the citizens of tomorrow. -

Thaw Escapes from Asylum 1Ultimatum Story Fabricated

tat IN STERLING GALT.EDITOR AND PROPRIETOR ESTABLISHED OVER A QUARTER OF A CENTURY TERMS-91.00 A YEAR ADVANCE VOL. XXXV EMMITSBTJRG, MARYLAND. FRIDAY, AT:( UST 22, 1913 NO. 20 ESCAPES FROM ASYLUM 1ULTIMATUM STORY FABRICATED THAW FROM ALL goi *Zit" FALSE STATEMENT USED TO INFLUENCE PUBLIC SLAY ER OF STANFORD WHITE GAINS FREEDOM 1114 ,f7,:try.f If 4 ** iefriatibiS idiffititS I Huerta Adherents---Press Ordered to Matteawan Attendant Held For Connivance in Sensa- alltitarittar 1.111100.11ii COMS'ASS Device to Help tional Plot.---Rescue Accurately Planned. btiorAmikilk joiRIMINIPAVE Withhold Denial 24 Hours DEMAND—WILSON IS HOPEFUL FLEES IN HIGH POWERED A(JTOMOBILE.—CAPTURED IN CANADA 1rN 411.144# DISCLAIMS ALLEGED RECOGNITION Mediation After Conference with Special Repre- Recognized by a Deputy Sheriff On a Train. —Fugitive Will Fight Against Southern Government Rejects Settlement Expected—Lind and Huerta Still Extradition. —May Be Returned to State of New Hampshire.—Counsel Friday ; Two small sons of Joseph Leveille, a sentative Lind—Amicable Contained—War Scare Caused Secures Habeas Corpus. —Canadian Government Aims To Return Fugitve Rev. Charles V. Holbrook, an Ameri- rancher near Belle Fouche. S. D., ate a Negotiating—What the American Note to New York State. can missionary,was shot and killed near basket of cherries and consumed a quart By One Minister, Sivas, in Asiatic Turkey. of milk both dying a short time later. Harry Kendall Thaw, slayer of Stan- between the United States and the The Mexican ultimatum story utter- ent, however, that a formal recogni- Auguste Frederick Brosseau, aged 24, who John Lind, ford White,escaped from the Mattewan Dominion of Canada. -

What Happened ALONG the WAY

Annual Report 20What happened19 ALONG THE WAY... MISSION To empower people of all ages through an array of human services and advocacy MERIT Established in 1850, Waypoint is a private, nonprofit organization, and the oldest human service/children’s charitable organization in New Hampshire. A funded member of the United Way, Waypoint is accredited by the Council on Accreditation, is the NH delegate to the Children’s Home Society of America, and is a founding member of the Child Welfare League of America. WAYPOINT Statewide Headquarters P.O. Box 448, 464 Chestnut Street, Manchester, NH 03105 603-518-4000 800-640-6486 www.waypointnh.org [email protected] Welcome to Waypoint. This is our 2019 Annual Report. It was a good year. We’ll give you the highlights here. That way, you can get the picture of how we did in 2019, with your help, and then get right back to what you were doing... adjusting to life in unprecedented times while continuing to be an amazing human being who is making an impact. Here’s what you’ll find in this publication: uMission & merit statements uMessage from our leaders uPeople served by program uOutcomes measures of our work uFinancial overview uLegislative recap uDonor honor roll listing uBoard listing uHeadquarters information 1 Message from our Dear Friends, Leaders You know, we feel rather sorry for 2019. It got sandwiched between our milestone year of 2018 when we rebranded and changed our name to Waypoint, and 2020 when our world turned upside down. Now with a global pandemic, political divides, soaring unemployment, extreme natural disasters, civil unrest and an international uprising against racial injustice, the months before this seem to pale in comparison. -

(Willmar, Minn.) 1908-01-15

*>w «#j&mi#itw Pes ™&v<2 ,*"*»*• The Nebraska Republican state com Foster E. Percy of Mendota, m, mittee fixed the state convention for Willmar Tribune. committed suicide in Chicago. i&g&a March 11 at Omaha and declared for Prince Stanislas Poniatowskl, the TU* USE FILLS HEWS 8F IIHIESiTA. BT THE TRIBUNE PRINTING CO. Taft. head of the historic Polish house of Capt. Daniel Ellis, aged 79, the cele that name, is dead In Paris. - State Funds. WILLMAR. - - - MINN. brated union scout of East Tennessee, Gen. Hempartzoonian Boyadjian, ULf OF ITS JDKY St. Paul—The close of 1907 found died at his home near Elizabethtown, head of the Hunchakists, or Armenian the state treasury with a cash balance Tenn. Revolutionary society, is In New York WORK OF SECURING HEARERS of $555,285.13. The statement at the A schooner was wrecked on the to organize Armenians in America in close of business Dec. 31 showed an Diamond shoals, near Cape Hatteras, armed bands to help the society in its FOR NEW YORK TRIAL overdraft charged to the revenue BRIEF REVIEW OF and only two of the crew of seven effort to wrest their country from PROVES DIFFICULT. fund of $324,416.03, while other ^unds were saved. Turkey. ' § had a total of $879,701.16, distributed A very impressive service was held The new king of Spain has an A radical bank bill was presented Claus A. Spreckle, son of the big as follows: in Trinity church, Kristlania, on the nounced that he is going to waive the in the Illinois house at Springfield by sugar refiner, charges that the Amer MISS EDNA GOODRICH Soldiers' relief $32,743.85 day before the funeral of King Oscar, coronation ceremonies on which so H WEEK'S EVENTS Representative Templeman. -

Facts Are Stubborn Things": Protecting Due Process from Virulent Publicity

Touro Law Review Volume 33 Number 2 Article 8 2017 "Facts Are Stubborn Things": Protecting Due Process from Virulent Publicity Benjamin Brafman Darren Stakey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Brafman, Benjamin and Stakey, Darren (2017) ""Facts Are Stubborn Things": Protecting Due Process from Virulent Publicity," Touro Law Review: Vol. 33 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol33/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brafman and Stakey: Facts Are Stubborn Things “FACTS ARE STUBBORN THINGS”: PROTECTING DUE PROCESS FROM VIRULENT PUBLICITY by Benjamin Brafman, Esq.* and Darren Stakey, Esq.** *Benjamin Brafman is the principal of a seven-lawyer firm Brafman & Associates, P.C. located in Manhattan. Mr. Brafman’s firm specializes in criminal law with an emphasis on White Collar criminal defense. Mr. Brafman received his law degree from Ohio Northern University, in 1974, graduating with Distinction and serving as Manuscript Editor of The Law Review. He went on to earn a Masters of Law Degree (LL.M.) in Criminal Justice from New York University Law School. In May of 2014, Mr. Brafman was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Ohio Northern University Law School. Mr. Brafman, a former Assistant District Attorney in the Rackets Bureau of the New York County District Attorney’s Office, has been in private practice since 1980. -

Supreme Court of the United States

1st DRAFT SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Nos. 74-1055 AND 74-1222 W. T. Stone, Warden,! . Petitioner On Wnt of Certwran to the 74-1055 ' United States Court of Appeals Lloyd Ch;ies Powell. for the Ninth Circuit. Charles L. Wolff, Jr.,) . Warden, Petitioner, On Wnt of Cert1oran to the ?'4-1222 v United States Court of Appeale 'd L. R' for the Eighth Circuit. D av1 . 1ce. [May -, 1976] Mn. JusTICE PowELL delivered the opinion of the Court. Respondents in these cases were convicted of criminal offenses in state courts, and their convictions were af firmed on appeal. The prosecution in each case relied upon evidence obtained by searches and seizures alleged by respondents to have been unlawful. Each respondent subsequently sought relief in a federal district court by filing a petition for a writ of federal habeas corpus under- 28 U. S. C. § 2254. The question presented is whether a federal court should consider, in ruling on a petition for· habeas corpus relief filed by a state prisoner, a claim that evidence obtained by an unconstitutional search or sei zure was introduced at his trial, when he has previously been afforded an opportunity for full and fair litigation of his claim in the state courts. The issue is of consid erable importance to the administration of criminal justice. 74-1055 & 74-1222-0PINION 2 STONE v. POWELL I We summarize first the relevant facts and procedural history of these cases. Respondent Lloyd Powell was convicted of murder in June 1968 after trial in a California state court.