Team Teaching in English for Employees English Language Partners Hutt

This reflective practice paper sets out to examine, consider, improve and re-evaluate a teaching situation which began in May 2013. It is a small piece of action research in which a group of teachers examined their experience with English for Employees (E4E) classes, made a change to the teaching process involved and re-investigated the results. The reflective practice model I have used is Kolb’s experiential learning cycle where “active experimentation leads to a transfer of learning from current cycle to a new cycle” (Surgenor, 2011). There are four main components to the cycle: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, active experimentation.

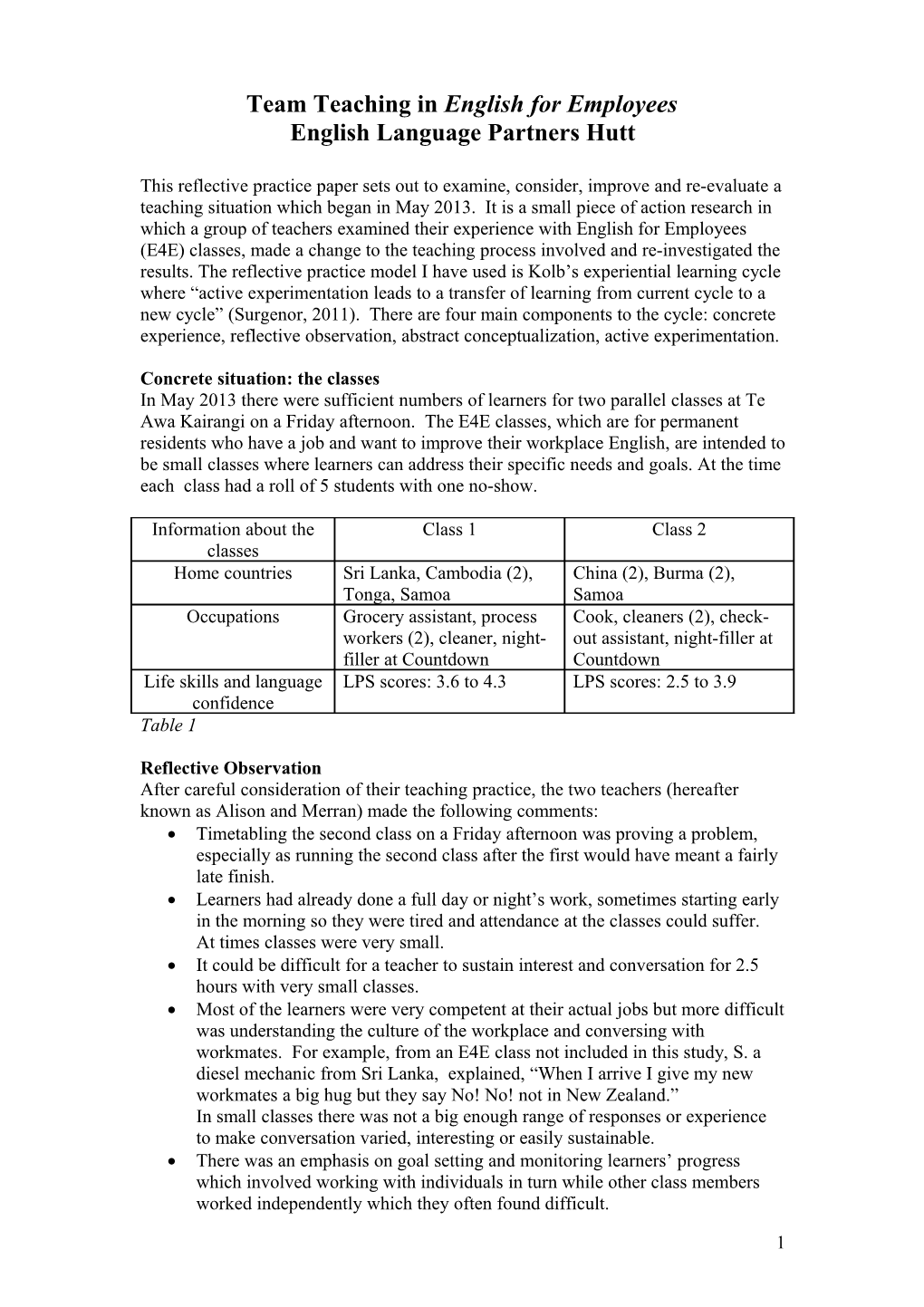

Concrete situation: the classes In May 2013 there were sufficient numbers of learners for two parallel classes at Te Awa Kairangi on a Friday afternoon. The E4E classes, which are for permanent residents who have a job and want to improve their workplace English, are intended to be small classes where learners can address their specific needs and goals. At the time each class had a roll of 5 students with one no-show.

Information about the Class 1 Class 2 classes Home countries Sri Lanka, Cambodia (2), China (2), Burma (2), Tonga, Samoa Samoa Occupations Grocery assistant, process Cook, cleaners (2), check- workers (2), cleaner, night- out assistant, night-filler at filler at Countdown Countdown Life skills and language LPS scores: 3.6 to 4.3 LPS scores: 2.5 to 3.9 confidence Table 1

Reflective Observation After careful consideration of their teaching practice, the two teachers (hereafter known as Alison and Merran) made the following comments: Timetabling the second class on a Friday afternoon was proving a problem, especially as running the second class after the first would have meant a fairly late finish. Learners had already done a full day or night’s work, sometimes starting early in the morning so they were tired and attendance at the classes could suffer. At times classes were very small. It could be difficult for a teacher to sustain interest and conversation for 2.5 hours with very small classes. Most of the learners were very competent at their actual jobs but more difficult was understanding the culture of the workplace and conversing with workmates. For example, from an E4E class not included in this study, S. a diesel mechanic from Sri Lanka, explained, “When I arrive I give my new workmates a big hug but they say No! No! not in New Zealand.” In small classes there was not a big enough range of responses or experience to make conversation varied, interesting or easily sustainable. There was an emphasis on goal setting and monitoring learners’ progress which involved working with individuals in turn while other class members worked independently which they often found difficult.

1 Abstract conceptualization After some discussion which included the centre manager, the teachers decided to trial a term of team teaching, a change that was suggested by one of the teachers who had had a very positive experience team teaching sixth form English. Team teaching involved “a group of instructors teaching regularly and co-operatively to help a group of students learn. As a team the teachers work together in setting goals for a course, designing a syllabus, preparing individual lesson plans, actually teaching students together and evaluating the results.” (Buckley, 2000, p4.)

Team teaching is a recognised pedagogic method which first was documented in the America of the mid-1950’s and was well established 10 years later. (Villa, Thousand, Narin, 2013). English educationalists adopted the technique a little later in the early 1960’s and by 1967 it was the subject of a positive nationwide survey conducted by John Freeman. (in Warwick, 1971, p17.)

Active Experimentation For the new cycle, instead of two classes there was one class with a slightly different makeup. A man from Sri Lanka had left and a high-level learner from Vietnam had been added to the group. The new class had a roll of 10 learners and was taught by Alison and Sue for six weeks while Merran was overseas. Merran resumed her teaching role when she returned to New Zealand.

Information about the new class 28 July, 2103 Home countries China (2), Burma (2), Samoa (2), Cambodia (2), Tonga and Vietnam Occupations process workers (2), night-fillers at Countdown (2), cleaners (3), cook, check-out assistant and administrator Life skills and language LPS scores ranged from 2.9 to 4.5 confidence Table 2

It was expected that Alison would be the lead teacher as she was most experienced but the working relationships between the two teachers (in practice, three) would vary between parallel and supportive.

All three teachers observed immediate advantages to the new cycle: Teachers could capitalize on their strengths. For example, Alison is an expert on pronunciation, spelling and grammar, Merran usefully steered planning to work-related material and Sue introduced a role-play based on a work accident. Teachers shared planning, goal-setting, class contact and evaluation so that they learned from each others’ strengths. For example, “Alison’s” deliberate pacing of a lesson made the other two teachers evaluate the speed of their delivery. Also, Alison was prepared to hold a silence and wait (and wait) for an answer, which generally elicited a response. (Palmer J Parker refers to this practice in his book The Courage to Teach: “…it is indisputable that the moment I break the silence, I foreclose on all chances for authentic learning. Why would my students think their own thoughts in the silence when they know I will invariably fill it with thoughts of my own.” (Palmer, 1998, p82) The shared insights became a form of in-service training.

2 It was easier to provide individual attention for learners, using a second teaching space if required. There was a small office available in the building which we could use if other rooms were busy – which was generally the case. For example, one teacher could concentrate solely on an LPS or ILP while the rest of the learners were engaged with the other teacher. Also Sue planned and implemented extension writing practice for a high level learner who would like to work in a library. Discussions, sometimes based on learners’ talks or current events, were wide- ranging, more easily sustainable and enjoyable. There was a greater range of response and experience available in the new combined class. (cf Tables 1 and 2) Although Merran was overseas for six weeks of the course, Alison provided continuity for all the learners and for Sue who was the relieving teacher. Equipment, such as a lap-top computer, always worked in the end but sometimes it took a while to get going. Sue was able to improvise a relevant pre-DVD discussion for the class while Alison coped with the technology. There was a 6.6 earthquake at the end of one class which caused most people to dive under desks. It was reassuring to have another responsible person to help support learners some of whom were frightened. The professional communication required strengthened the personal relationships between the teachers and built “a sense of community.”

The learners recorded their opinions of team teaching by ranking some statements on a 1-5 scale. Their typically favourable responses are shown on the spreadsheet we have handed around. I should perhaps note that learner No 7 was a high level learner who would have liked a small class of learners at her own level. After discussing her reaction to the class with her individually it seemed that she was unhappy with multilevel classes rather than team teaching. On her response sheet, under Any other comments? she wrote,” I think if we have a small class with the same level of students, maybe it is easier for us to study. But I also like to have two teachers in the class.”

There were advantages for the centre manager and administrators too as Christine Cook records: 1 room booking (where teaching spaces are at a premium) Back up tutor readily available (in case of sickness or, as here, overseas travel) Flexibility with scheduling that caters to a fluctuating demand without the need for a waiting list. Mentoring for new tutors Addresses safety/security issues that could arise for individual tutors working in isolation, perhaps at night. Less paper work to chase.

Although the response of manager, teachers and learners to this experiment was largely positive, I can foresee some possible difficulties or at least caveats. Teachers need to be compatible. A shared planning and evaluation time is essential but may be difficult to organize.

3 Good communication is always essential in teaching but with team teaching, a willingness to listen and share as well as a sense of humour may well determine the success of the project. Conclusion The new cycle of team teaching for these two E4E classes was endorsed by the centre manager, teachers and most of the learners. Management recorded that team teaching enabled more experienced teachers to work with new teachers and also to provide back-up in a variety of situations. There was less pressure on teaching space, more flexibility of enrolment to courses, less paperwork and, because there were two teachers together, less concern about safety/security issues.

The teachers reported that the programme invited flexibility of content, techniques and style. They learned from each others’ strengths and also from occasions when the learners had been less responsive by discussing what they could have done differently. Planning, preparing resources, class contact and evaluation were all discussed, generally in 30-40 minute meetings after each class.

The learners were largely enthusiastic, rating highly the chance to learn different things from different teachers and the opportunity for more individual attention. With one exception, the plan to continue team teaching was rated 4 on a 1-5 scale where 1 indicated complete disagreement and 5 registered enthusiastic agreement with the policy.

While the caveats listed above deserve careful attention, the new learning cycle presented many advantages for all those involved and perhaps this reflective practice paper could provide a basis for discussion for other teachers who might consider team teaching.

List of References Andrew, M. (2009). Reading and Spelling Made Simple. NZ: Simpli Reading Buckley, F. (2000). Team Teaching: What, Why, and How? California: Sage Publications Palmer, P. (1998). The Courage to Teach. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Surgenor, P. (2011) Reflective Practice. From www.ucd.ie/teaching. Villa, A., Thousand, J., Nevin,A. (2013) A Guide to Co-Teaching. USA:Corwin Warwick, D. (1971). Team Teaching. London: University of London Press.

With thanks to: Participants: Alison White, Merran Bakker, Sue Barlow Centre Manager: Christine Cook

Writer: Sue Barlow (for English Language Partners, Hutt.)

4