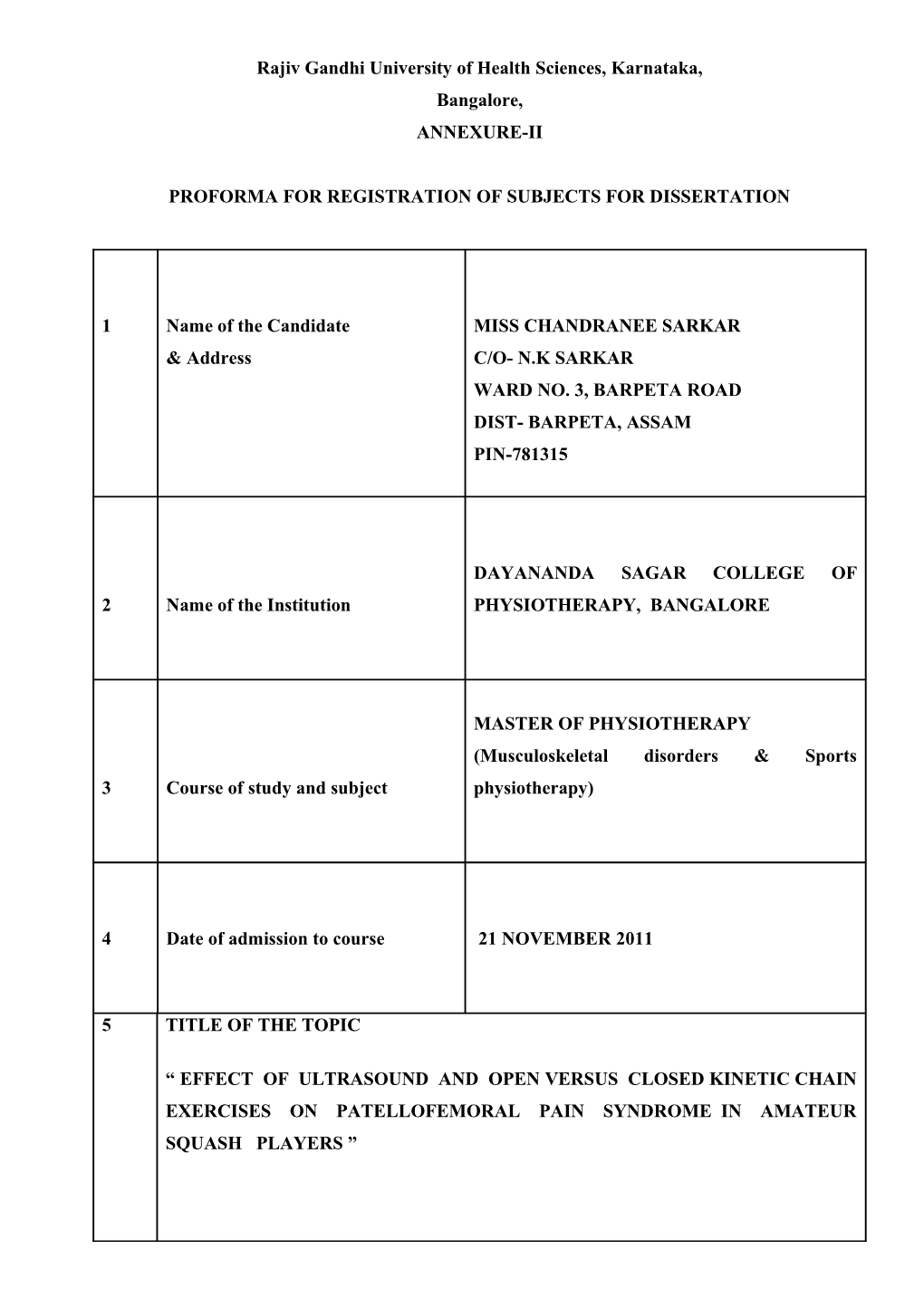

Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Karnataka, Bangalore, ANNEXURE-II

PROFORMA FOR REGISTRATION OF SUBJECTS FOR DISSERTATION

1 Name of the Candidate MISS CHANDRANEE SARKAR & Address C/O- N.K SARKAR WARD NO. 3, BARPETA ROAD DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM PIN-781315

DAYANANDA SAGAR COLLEGE OF 2 Name of the Institution PHYSIOTHERAPY, BANGALORE

MASTER OF PHYSIOTHERAPY (Musculoskeletal disorders & Sports 3 Course of study and subject physiotherapy)

4 Date of admission to course 21 NOVEMBER 2011

5 TITLE OF THE TOPIC

“ EFFECT OF ULTRASOUND AND OPEN VERSUS CLOSED KINETIC CHAIN EXERCISES ON PATELLOFEMORAL PAIN SYNDROME IN AMATEUR SQUASH PLAYERS ” 6 Brief resume of the intended work :

6.1 INTRODUCTION

Squash is a high-intensity sport that requires high-speed movements around the court while maintaining control over ball placement and being aware of the spatial orientation of the opponent. In order to hit the ball, squash players need large range of joint motion and velocity of limb action.

Injury risk factors in squash include the physical demands of the sport, the speed, size and physical properties of the ball, court surfaces, the confined area of play and close proximity of players while swinging a racket. The general injury prevalence among squash players is about 45%. [1]

A critical review of squash epidemiological studies indicated that squash players most commonly report acute soft-tissue injuries at hospital emergency departments. Lower-limb injuries account for the majority of the injuries sustained by squash players. The knee and ankle joint are reportedly the most commonly injured body regions in squash. Some of the factors that may increase your risk of injury include age, poor fitness level, poor technique - puts unnecessary strain on joints and muscles.[1]

In this sport, 58% of injuries affected the lower limb. Injuries in squash players most frequently affected the knee, lumbar region, ankle and muscles, especially the calf . Squash players face up more injuries (59%) in comparison with the tennis (21%) and badminton (21%) ones. On the other hand, injuries to the lower limbs in squash are common and relate to the acute physical stresses increase in the nature of the sport, as well as the more chronic overuse type of injuries. Since players are active for most time of the game, they may face more sport injuries.[2]

A study showed that knee injuries seen in squash players are collateral ligament (33%), patello femoral (23%), patella dislocation, meniscal (19%), cruciate ligament (6.8%) traumatic synovitis (9%) other (6.7%) [2]

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is described in the literature as anterior knee pain, caused by aberrant motion of the patella in the trochlear groove, which results from biochemical and/or physical changes within the patellofemoral joint (PFJ). PFPS exists without gross abnormality of the articular cartilage. It is a problem of chronic overload of the muscles of the lower extremity.[3] Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is a common musculoskeletal complaint characterised by pain in front of the knee which is provoked by activities such as walking up and down stairs, sitting with flexed knees for long periods, running, kneeling and squatting[4]

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is usually due to weakness of vastus medialis obliqus (VMO) resulting in abnormal patellar tracking.[5]

Pain at the front of the knee or ''behind the knee cap'' is a common problem for many sports people and can be very debilitating. This condition has a number of names including ''Patello-femoral Pain Syndrome'' & "Runners Knee". The problem occurs between the patella (kneecap) and the femur (thigh bone). Under normal circumstances, the kneecap presses against the lower portion of the thigh bone when the knee is in a bent position.[6,7]

Patellofemoral syndrome (PFPS) is one of the most common joint complaints and affects athletes and non-athletes alike. PFPS patients report of symptoms of anterior knee pain, aggravated by functional activities. Patellar crepitation, swelling and locking are other symptoms.[8]

During running or any step, squat or landing & jumping activity, the kneecap moves up and down or ''tracks'' against the thigh bone and in so doing, acts as a fulcrum, which provides a mechanical advantage for the front thigh muscles (the quadriceps). High forces are produced between the kneecap and thigh bone during such activities. Decreased soft- tissue flexibility is also evident in adolescents due to the inability of soft tissues to accommodate the rapid growth of skeletal structures such as the long bones.[9,10]

There is a commonly accepted concept that conservative rehabilitation induces symptom relief for PFPS patients. Different treatments can be tried to reduce the pain and difficulties experienced during daily activities, including drugs, electric modalities and massage. Exercise regimens to strengthen the muscles surrounding and supporting the knee are other options.[10]

Young squash players are now participating at relatively more competitive levels of play compared with 20 years ago. This shift in focus among young people from enjoyment of physical activity to competitiveness is placing high demands on the musculoskeletal and physical systems. Injury risk factors in squash include the physical demands of the sport, the speed, size and physical properties of the ball, court surfaces, the confined area of play and close proximity of players when swinging a racket.[11]

As with many musculoskeletal conditions, multiple biophysical agents, such as ultrasound, electrical stimulation, and ice, are also often used to treat individuals with PFPS. Therapeutic ultrasound is one of many rehabilitation interventions available for reducing pain and inflammation. “Ultrasound is a form of mechanical energy consisting of high frequency vibrations”. These vibrations result in acoustic streaming and radiation forces, both of which enhance the flow of particles from one side of a cell membrane to the other. Thus, ultrasound increases cell permeability. As a result of stable cavitation ultrasound also “exerts mechanical stresses on the surrounding cells or other structures. Pulsed ultrasound is generally recommended for treatment of pain and inflammation in acute stages, while the continuous ultrasound is recommended for treatment of restricted movement.[12,13]

Open kinetic chain (OKC) exercises are single joint movements that are performed in non-weight bearing with a free distal extremity. In contrast closed kinetic chain (CKC) exercises are multi-joint movements performed generally in weight bearing with a fixed distal extremity. The treatment often includes quadriceps femoris muscle strengthening exercises in an open kinetic chain (OKC) or closed kinetic chain (CKC).[14]

A study showed that OKC and CKC exercises promoted a reduction in the pain intensity and improvement of the functionality in PFPS bearers. The force unbalance between the vastus medialis oblique (VMO) and the vastus lateralis (VL) muscles, which are the main dynamic stabilizers of the patella is considered the main factor that causes the symptoms onset. [14]

6.2 Need for the study :- The reviews of literature on PFPS have found some evidence that exercise therapy might help to reduce the pain of PFPS. There are many studies that talk about the effect of OKC and CKC exercises on PFPS but there are hardly any literature available on the combined effect of ultrasound and exercises on PFPS, So the aim of this study is to find out whether exercise therapy along with ultrasound has any effect in the reduction of pain of PFPS in amateur squash players.

6.3 Hypothesis :- Null hypothesis: There will be no effect of ultrasound and open versus closed kinetic chain exercise in patellofemoral pain syndrome in amateur squash player.

Experimental hypothesis: Ultrasound and open versus closed kinetic chain exercise will help to reduce pain and improve muscle strength of patellofemoral pain syndrome in amateur squash players.

6.4 Review of Literature:-

Outcome measures:-

Tugba Kuru, Elif Elçin et al;(2009) :Validity of the Turkish version of the Kujala patellofemoral scoring patellofemoral pain syndrome. There has been no functional assessment scale validated for Turkish patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Internal consistency of the Turkish version of the Kujala patellofemoral score showed good reliability and test-retest results showed high reliability, suggesting that it is an appropriate functional instrument for Turkish patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cronbach’s alpha calculated for internal consistency of the Kujala patellofemoral score was 0.84. Correlation coefficients of the items to estimate test-retest reliability ranged from 0.613 (p=0.004) to 1.000 (p=0.000), with the mean correlation coefficient of 0.944 (p=0.000). [17]

Roos em, Klässbo M, Lohmander Ls.womac (1999): Osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Test-retest reliability, internal consistency, validity, and responsiveness were determined in 52 patients with arthroscopically assessed cartilage damage of the tibio-femoral knee joint. The Swedish version of WOMAC is a reliable, valid, and responsive instrument with metric properties in agreement with the original widely used version.[22]

Bert m. chesworth e lsie g. culham et al;(1989): Validation of Outcome Measures in Patients with Patellofemoral Syndrome. The purpose of this study was to determine the reliability and validity of the following outcome measures in a group of 18 patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome, the visual analog pain scale (VAS), a functional index questionnaire (FIQ), selected temporal components of gait on level walking and ascending stairs, knee joint angle on downhill walking, and electromyographic activity of the quadriceps during stair climbing. Subjects were tested at initial assessment (time 0), after 24 hours (time I), and after clinically significant improvement, following a course of treatment (time 2). Using the intra-class correlation coefficient (r,), the VAS (r, = 0.603) and FIQ (r, = 0.483) exhibited a poor day-to-day reliability (time 0 versus time 1).[20]

Squash injuries:-

L Meyer Q Louw et al;(2007): Prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries among adolescent squash players in the Western Cape. The aim of the study is to determine the prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries among adolescent squash players in the Western Cape. Injury data were collected for 106 players at three schools randomly selected from a list of the top 10 schools in the Western Cape high school squash league of 2005. An adapted structured self- administered questionnaire based on a previously validated musculoskeletal injury questionnaire was used to collect the data. The main variables investigated were prevalence, mechanism and injury site of musculoskeletal squash injuries. Authors concluded that a relatively high prevalence of squash injuries was found.[1]

K. Steininger, Dr. med. and R. E. Wodick, et al;(1987): Sports-specific fitness testing in squash. The field test was performed in a squash court. Six light bulbs were connected to a programming device causing individual bulbs to light up in a given sequence. The players were instructed to react to the flashes by running towards and striking balloons mounted in the vicinity of the bulbs. The results show that a valid estimate of fitness can be derived from measurements involving exercise closely resembling that which is specific for the sports activity in question. Improved training advice and guidance may result from such studies.[18]

M. D. Chard, and S. M. Lachmann et al;(1987): Racquet sports patterns of injury presenting to a sports injury clinic. The purpose of this study was to investigate and compare the pattern of injuries presenting to a sports injury clinic in players of the racquet sports squash, badminton and tennis. In an 8-year retrospective study, 631 injuries due to the racquet sports of squash (59%), tennis (21%) and badminton (20%) were seen in a sports injury clinic, males predominating (58 to 66%). So the study concluded from detailed assessment of 106 cases showed many to be new, infrequent, social players. Poor warm-up was a common factor in new and established players.[2]

Burton L. Berson et al;(1981): An epidemiologic study of squash injuries. A retrospective investigation of squash-related injuries incurred at a private and a public club in New York was undertaken to gain insight into the incidence and nature of such injuries. Telephone interviews were conducted with 200 randomly selected individuals to obtain their entire injury history. Sixty-nine of the 155 squash players contacted sustained injuries during their participation. Some had multiple injuries. This resulted in an overall injury rate of 44.5%. Nearly one-half of the injuries involved the lower extremity, with the lower leg being injured most often. Forty-seven percent of the injuries seen were considered disabling because the patients were out of action for more than two weeks after injury. Only rarely will an injured squash player become permanently impaired.[21]

PFPS and interventions:-

Heintjes EM, BergerM et al; (2009): Conducted a study to find out exercise therapy for patella femoral pain syndrome. This review aims to summarize the evidence of effectiveness of exercise therapy in reducing anterior knee pain and improving knee function in patients with PFPS. From 750 publications 12 trials were selected. All included trials studied quadriceps strengthening exercises. The study concludes that exercise therapy is more effective in treating PFPS than no exercise was limited with respect to pain reduction, and conflicting with respect to functional improvement. There is strong evidence that open and closed kinetic chain exercise are equally effective.[7]

Brosseau L, Casimiro L, Welch V, et al; (2009): Therapeutic ultrasound for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome. To assess the effectiveness and side effects of ultrasound therapy for treating patellofemoral knee pain syndrome. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), case-control and cohort studies comparing therapeutic ultrasound against placebo or another active intervention in people with patellofemoral pain syndrome were selected according to a prior protocol, Ultrasound therapy was not shown to have a clinically important effect on pain relief for people with patellofemoral pain syndrome. These conclusions are limited by the poor reporting of the therapeutic application of the ultrasound and low methodological quality of one of the trial included. No conclusions can be drawn concerning the use, or non-use, of ultrasound for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome. More well-designed studies are needed.[13]

Anil Bhave, Erin Baker et al(2008): Conducted a study Prescribing Quality Patellofemoral Rehabilitation before Advocating Operative Care. The study has classified patients in three categories of pain level: acute, sub-acute, or chronic. Authors conclude that Prescribing Quality Patellofemoral Rehabilitation before Advocating Operative Care, in the acute phase, the goal of therapy is to reduce inflammation, increase patellar mobility, and improve quadriceps strength. If lateral structures are tight, then pulsed ultrasound are useful to break up scar tissue and improve flexibility.[15]

Cristina Maria Nunes Cabral1, Angela Maria de Oliveira Melim et al; (2007): Effect of a closed kinetic chain exercise protocol on patellofemoral syndrome rehabilitation. The purpose of this study was to verify the efficacy of quadriceps femoris muscle strengthening exercises in a closed kinetic chain (CKC) in the treatment of patellofemoral syndrome. The 10 PFPS patients performed quadriceps femoris strengthening exercises using a leg-press with progressive increase in resistance during eight weeks, twice a week. The results of the present study permit the suggestion that the proposed quadriceps femoris strengthening exercises with ROM control should be prescribed for PFPS patients since, they improve the knee functional level. Moreover, progressive resistance increases according to the pain level should be used in patients with muscle skeletal disorders to protect the joints.[9]

Guilherme Lotierso Fehr1, Alberto Cliquet Junior et al;(2006): Effectiveness of the open and closed kinetic chain exercises in the treatment of the patellofemoral pain syndrome. The aim of this study was to analyze the therapeutic effects of the open kinetic chain and closed kinetic chain exercises to treat the patellofemoral syndrome. 24 volunteers were randomly divided in two groups: group (I) performed the OKC exercises; group (II) performed the CKC exercises. Both groups were submitted to eight consecutive weeks of treatment consisting of three weekly sessions performed in alternate days. The results found in this study suggest that according to the conditions of the trial, the OKC and CKC exercises provoke no changes in the patterns of the EMG activation in the VMO and VL muscles.[16]

Ann-katrin stensdotter, paul W. Hodges,et al;(2003): Quadriceps Activation in Closed and in Open Kinetic Chain Exercise. The aim of this study was to examine whether the quadriceps femoris muscles are activated differently in open versus closed kinetic chain tasks. Ten healthy men and women extended the knees isometrically in open and closed kinetic chain tasks in a reaction time paradigm using moderate force. Surface electromyography (EMG) recordings were made from four different parts of the quadriceps muscle. The onset and amplitude of EMG and force data were measured. Authors concluded that, exercise in closed kinetic chain promotes more balanced initial quadriceps activation than does exercise in open kinetic chain. This may be of importance in designing training programs aimed toward control of the patellofemoral joint.[14]

Danielle A.W.M. van der Windt (1999): Ultrasound therapy for musculoskeletal disorders a systematic review. The objective of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of ultrasound therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders. Data from the original publications were used to calculate the differences between groups for success rate, pain, disability and range of motion. Statistical pooling was performed, if studies were homogeneous with respect to study populations, interventions, outcome measures and timing of follow-up. Study concluded there is a little evidence to support the use of ultrasound therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.[23]

6.5 Objective of the study : To compare the effect of ultrasound and open versus closed kinetic chain exercise on patellofemoral pain syndrome in amateur squash players.

7 Materials and Methods:

7.1 Source of data :- Sports complex at Dayananda sagar college, Bangalore. Squash center at Jayanagar 5th block, Bangalore. Country club, Sarjapur road, Bangalore.

7.2 Method of collection of data:-

Population : Amateur squash players. Sample design : Simple random sampling. Sample size : 30 Type of Study : Comparative study. Duration : 8 months.

7.3 Inclusion criteria:- 19 to 40years of age. Amateur squash players diagnosed with PFPS. Both males and females will be included.

7.4 Exclusion criteria:- Non cooperative patients. Orthopedic surgery around the knee. Neurological and cardio vascular diseases, radicular pain, Referred pain. Positive clinical tests or imaging consistent with meniscal or ligamentous involvement. Limb length discrepancy. Degenerative joint diseases. Congenital deformities. Non squash players.

7.5 Materials required :-

Therapeutic Ultrasound. Ultrasound Gel. Quadriceps table.

Measuring tools:- WOMAC questionnaire. KUJALA scale. VAS scale. Manual muscle testing (MMT).

7.6 Methodology

Intervention to be conducted on participants:-

Subjects who fulfill the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be included in the study and an informed consent will be taken from each of the subjects prior to participation. Instructions are given to the subjects about techniques performed.

A total of 30 subjects will be divided equally into 2 groups by random lottery method. Group A (n=15) Group B (n=15); Group A will receive closed kinetic exercises and ultrasound, Group B will receive open kinetic exercises and ultrasound.

As to the dynamic CKC exercises (450 leg press) and the OKC exercises (quadriceps table), one repetition maximum (RM) of the quadriceps for each subject is found. The treatment protocol consists of three weekly physiotherapy sessions performed along eight weeks in alternate days and standard progressive resisted exercise programme (PRE) protocol is followed for strengthening quadriceps. Review to be taken after every two month and outcome measures are taken before and after the treatment.

Testing procedure:-

Group A: To the group submitted to the CKC protocol in both static and dynamic, the subjects would perform during the semi-squatting exercise in its eccentric phase (down) and in the concentric phase (up). From the stand up position, the volunteers will perform five repetitions of the squatting and rising movements, and one minute rest will be granted between each set. Exercises will be performed for five repetitions and gradually progressed, exercises are static exercise of the quadriceps with the knees at a 200 angle, static exercise of the quadriceps with the knees at a 400 angle, Semi squatting (00 to 500), Leg press (00 to 500). After exercise subject will undergo ultrasound therapy with an intensity of 1W/cm2 for 8 minutes using a pulsed mode 1: 1 ratio with frequency of 1MHz.

Group B: To the group submitted to the OKC protocol, the data collections would perform on a quadriceps table. The volunteers will remain seated having their lumbar and thoracic spine supported hips and knees at a 900 flexion. Next, they will perform five repetitions and gradually progress according to progressive resisted exercise programme (PRE). Exercises are extension movement (concentric phase), and flexion of the knees (eccentric phase), and one minute rest will be granted between each set. After exercise, the subject will undergo ultrasound therapy with the intensity of 1W/cm2 for 8 minutes using a pulsed mode 1: 1 ratio with frequency of 1MHz.(24)

These criteria were adopted following the studies performed by Steimkamp et al. and Escamilla et al, who suggested these angles as the most safe to perform the OKC and CKC exercises.(14)

Outcome measures :- VAS for pain. Manual muscle testing for Muscle power. WOMAC and KUJALA for functional outcome.

Statistics:- Data analysis will be performed by SPSS (version 17) for windows. The alpha value will be set as 0.05. Descriptive statistics will be used to find out mean, standard deviation and range for demographic and outcome variable. Man Whitney U test will be used to find out the homogeneity for base line and demographic and outcome variable. Chi square test will be used to find out gender differences among the two groups. Microsoft word, excel will be used to generate graph and tables etc.

7.7 Ethical Clearance :- As this study involve human subjects, the ethical clearance has been obtained from the ethical committee of DAYANANDA SAGAR COLLEGE OF PHYSIOTHERAPY, BANGALORE, as per ethical guidelines research from biomedical research on human subjects, 2000, ICMR, New Delhi.

8 List of References:-

1. L Meyer, L van Niekerk, E Prinsloo, M Steenkamp, Q Louw. Prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries among adolescent squash players in the Western Cape. SAJSM vol 19 No. 1 2007. 2. M. D. Chard and S. M. Lachmann. Racquet sports patterns of injury presenting to a sports injury cunic. Brit.J.Sports Med- 1987, December Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 150-153.

3. S.T. Green. Patellofemoral syndrome, Judah Street 2717, San Francisco, Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies (2005) 9, 16–26

4. Konstantinos D. Papadopoulos, Jane Noyes, Moyra Barnes, Jeremy G. Jones, Jeanette M. Thom. How do physiotherapists assess and treat patellofemoral pain syndrome in North Wales? A mixed method study. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, May 2012, Vol 19, No 5.

5. G.y.f, a.q. Zhang a. Biofeedback exercise improved the EMG activity ratio of the medial and lateral vasti muscles in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. G.Y.F. Ng et al. / Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 18 (2008) 128–133.

6. Erik Witvrouw, S. Werner, C. Mikkelsen, D. Van Tiggelen, L. Vanden Berghe, G. Cerulli. Clinical classification of patellofemoral pain syndrome: guidelines for non- operative treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc (2005) 13: 122–130.

7. Heintjes EM, Berger M, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Bernsen RMD, Verhaar JAN, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome (Review).The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 1.

8. Cristina Maria Nunes Cabral1, Angela Maria de Oliveira Melim, Isabel de Camargo Neves Sacco, Amelia Pasqual Marques. Effect of a closed kinetic chain exercise protocol on patellofemoral syndrome rehabilitation. , Ouro Preto – Brazil, ISBS Symposium 2007;688.

9. Carina D. Lowry, Management of Patients with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome Using a Multimodal Approach: A Case Series. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 38 | number 11 | November 2008 | 691.

10. Christian J. Barton, Hilton B. Menz. Evaluation of the Scope and Quality of Systematic Reviews on Non-pharmacological Conservative Treatment for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 38 number 9 September 2008 | 529.

11. Eime R, Zazryn T, Finch C. Epidemiology of squash injuries requiring hospitaltreatment. Inj Control Saf Promot 2003; 10:243-5.

12. David A. Lake, Nancy H. Wofford. Effect of Therapeutic Modalities on Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach March/April 2011vol. 3 no. 2 182-189.

13. Brosseau L, Casimiro L, Welch V, Milne S, Shea B, Judd M, Wells GA, Tugwell P. Therapeutic ultrasound for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome (Review). The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 1.

14. Ann-Katrin Stensdotter, Paul W. Hodges, Rebecca Mellor, Gunnevi Sundelin1, And Charlotte Ger-Ross, quadriceps. Activation in Closed and in Open Kinetic Chain Exercise. Submitted for publication December 2002.

15. Anil Bhav, Erin Baker, Prescribing Quality Patellofemoral Rehabilitation before Advocating Operative Care. Rubin Institute for Advanced Orthopedics 2008.

16. Guilherme Lotierso Fehr1, Alberto Cliquet Junior, Enio Walker Azevedo Cacho3 and João Batista de Miranda. Effectiveness of the open and closed kinetic chain exercises in the treatment of the patellofemoral pain syndrome. Rev Bras Med Esporte Mar/Abr, 2006. Vol. 12, No: 2; 3911-1345.

17. Anthony Keeley, Paul Bloomfield, Peter Cairns and Robert Molnar. Iliotibial band release as an adjunct to the surgical management of patellar stress fracture in the athlete: a case report and review of the literature. Sports Medicine Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology 2009. 30 July

18. K.Steininger and R. E. Wodick. sports-specific fitness testing in squash.BritJ.Sports Med. - Vol. 21, No. 2 June 1987, pp. 23-26.

19. Tugba Kuru, Elif Elçin Dereli, Yaliman. Validity of the Turkish version of the Kujala patellofemoral score in patellofemoral pain syndrome. Kuru et al. Validity of the Turkish version of the Kujala patellofemoral score in patellofemoral pain syndrome. December 2, 2010 Turkish Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology.153.

20. Bert M. Chesworth, E Lsie G. Culham, G. Elizabeth Tata, M Alcolm Peat. Validation of Outcome Measures in Patients with Patellofemoral Syndrome, 302 chesworth et al jospt, February 1989.

21. Burton L. Berson. An Epidemiologic Study Of Squash Injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. March 1981 vol. 9 no. 2 103-106.

22. Roos EM, Klässbo M, Lohmander LSScand J Rheumatol. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities.1999; 28:210- 5.

23. Daniëlle A.W.M. van der Windt, Geert J.M.G. van der Heijden, Suzanne G.M. van den Berg, Gerben ter Riet, Andrea F. de Winter, Lex M. Bouter. Ultrasound therapy for musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review.7 January 1999; accepted 11 January 1999.

24. Sheila Kitchen. Electrotherapy-evidence based practice. Eleventh edition,2006.page no 222-227

Signature of Candidate: 9

10 Remarks of the Guide : 11 Name and Designation of

11.1 Guide : DR ANIL T JOHN

11.2 Signature :

11.3 Co-Guide : DR JIMSHAD T U

11.4 Signature :

11.5 Head of Department : DR ANIL T JOHN

11.6 Signature :

12 12.1 Remarks of the Chairman & Principal:

12.2 Signature :