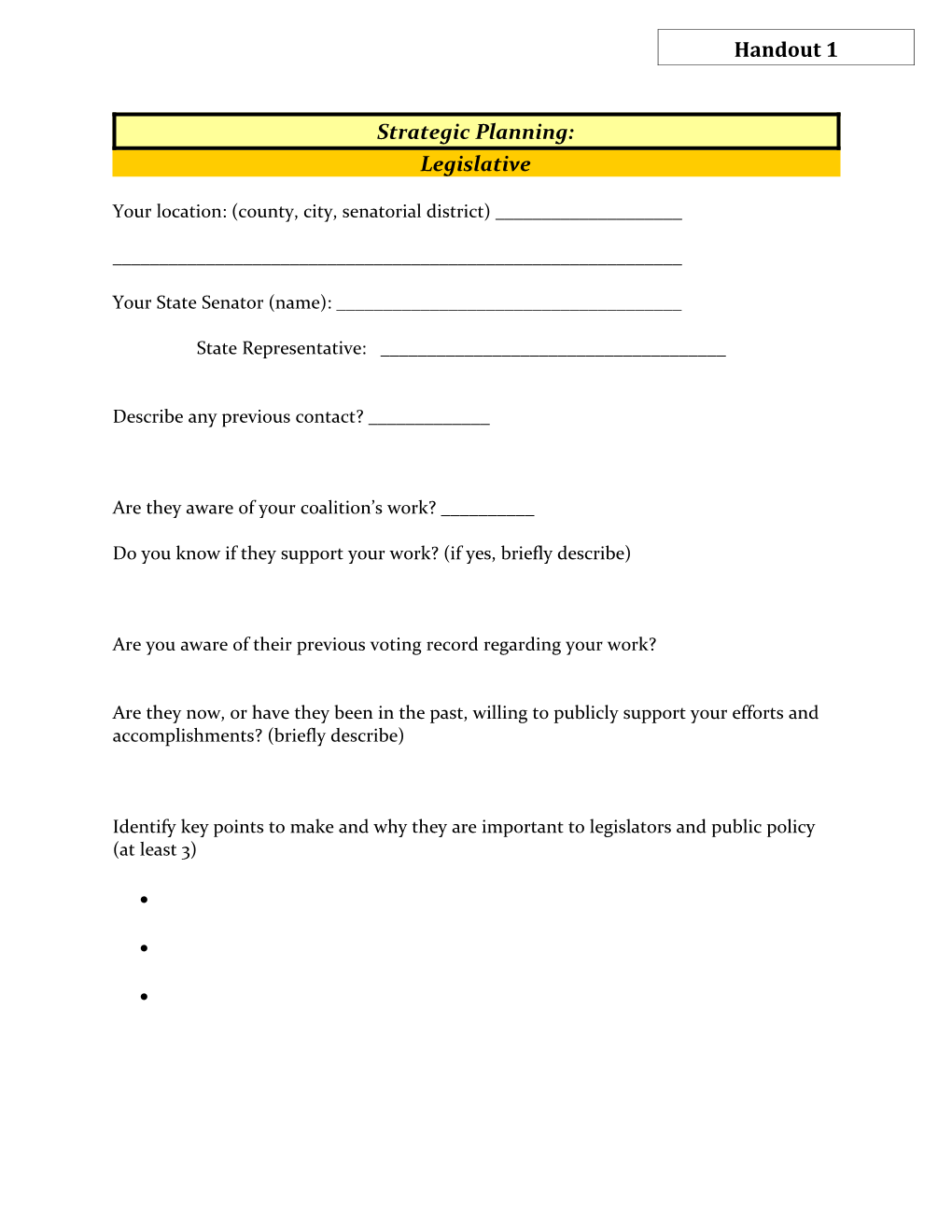

Handout 1

Strategic Planning: Legislative

Your location: (county, city, senatorial district) ______

______

Your State Senator (name): ______

State Representative: ______

Describe any previous contact? ______

Are they aware of your coalition’s work? ______

Do you know if they support your work? (if yes, briefly describe)

Are you aware of their previous voting record regarding your work?

Are they now, or have they been in the past, willing to publicly support your efforts and accomplishments? (briefly describe)

Identify key points to make and why they are important to legislators and public policy (at least 3)

Handout 2

The Ten Informal Rules of Advocacy or Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Advocacy But Never Thought to Ask

1. Consider Yourself an Information Source. Legislators have limited time, staff, and interest on any one issue. They can’t be as informed as they might like on all the issues – or the ones that concern you. You can fill the information gap.

2. Tell the Truth. Never give false or misleading information to a legislator.

3. Know Who Else is on Your Side. It is helpful for a legislator to know what other groups, individuals, state agencies and/or legislators are working with you on an issue.

4. Know the Opposition. Anticipate who the opposition will be – organized or individual. Tell the legislator what their arguments are likely to be and provide them with answers and rebuttals to those arguments.

5. Make the Legislator Aware of any Personal Connection You May Have . No matter how insignificant you may feel it is, if you have friends, relatives, and/or colleagues in common, LET THEM KNOW. Our legislative process is very informal and though it may make no difference in your effectiveness, it may make the difference.

6. Don’t be Afraid to Admit You Don’t Know Something . If the legislator wants information you don’t have, or asks something you don’t know, tell them and then offer to get the information they are looking for.

7. Be Specific About What You are Asking For. If you want a vote, information, answers to a question – whatever it is – make sure you ask directly and get an answer.

8. Follow Up. It is very important to find out if your legislator did what he/she said they would. It is very important that you then thank them if they did, or ask them for an explanation as to why they did not vote as they said they would.

9. Don’t “Burn any Bridges.” It is very easy to get emotional over issues you feel strongly about. That’s fine, but be sure that no matter what happens you leave your dealings on good enough terms that you can go back to them. Remember, your strongest opposition on one issue may be your strongest ally on the next.

10. REMEMBER YOU ARE THE BOSS ! Your tax money pays the legislators’ salaries, pays for the paper they write on, the phone they call you on. You are the employer and they are the employee. You should be courteous, but don’t be intimidated. They are responsible to you and nine times out of ten, legislators are grateful for your input. Handout 3

Pennsylvania Senate Standing Committees www.legis.state.pa.us

Aging & Youth

Agriculture & Rural Affairs Appropriations

Banking & Insurance

Communications & Technology

Community, Economic & Recreational Development

Consumer Protection & Professional Licensure Education

Environmental Resources & Energy

Finance

Game & Fisheries

Intergovernmental Operations Judiciary

Labor & Industry Law & Justice

Local Government Public Health & Welfare

Rules & Executive Nominations

State Government Transportation

Urban Affairs & Housing

Veterans Affairs & Emergency Preparedness Handout 4 Pennsylvania House Standing Committees www.legis.state.pa.us

Aging & Older Adult Services

Agriculture & Rural Affairs Transportation

Appropriations Urban Affairs

Children & Youth Veterans Affairs & Commerce Emergency Committee On Committees Preparedness Committee On Ethics

Consumer Affairs

Education

Environmental Resources & Energy

Finance

Game & Fisheries

Gaming Oversight

Health

Human Services

Insurance

Judiciary

Labor & Industry

Liquor Control

Local Government

Professional Licensure Rules

State Government

Tourism & Recreational Development Handout 5

Tips for Meeting a Legislator Make your best effort to schedule a meeting with your legislator. However, if that is not possible, you may need to meet with a legislative aide. Treat them with the same respect you would show your legislator. Remember that they are often a trusted advisor who your legislator may turn to for information and an opinion on your issue. Here are some tips for before, during and after a meeting with your legislator or a legislator’s aide:

Be prepared

Schedule an appointment. Contact your legislator’s office to request a meeting at their office or another convenient location. Let the scheduler know what topic you wish to discuss and who will be accompanying you, if anyone. Call to confirm the day before. If applicable, meet to coordinate. If there will be one or more joining you, meet or talk ahead of time to coordinate. Appoint a lead spokesperson and identify who will make what points or share experiences. Groups of two are often most effective. Groups of five or six also make a strong statement. Know your legislator. Look up your legislator’s bio and press releases. Research what committee(s) they are on. Know his or her history with your issue. Understanding their background, interests and roles will help you frame your message. If possible, compile information about the impact of prevention services in their district. Prepare a few dramatic numbers and anecdotes. Prepare your pitch. Be prepared for “five and fifteen.” Have a talk ready that can be made in five minutes if your legislator is hurried or needs to leave. Be ready with an extended version if you have longer. Be on time. Allow extra time to clear security and find your legislator’s office.

Introduce yourself. Keep it brief and thank your legislator for his or her time.

Address your legislator properly. Always address legislators with their elected title and last name. If they request that you use their first name, then you may do so. Example: Hello, [Senator Smith or Representative Jones]. Make introductions. Keep this to a name and city or town and affiliate or role. Example: I’m (name) and I’m from (county or city). Show appreciation. Let your legislator know that you appreciate his or her time to hear your concerns on prevention issues. You may want to thank your legislator if he or she has shown support for your issues in the past. Example: Senator Smith, Thank you very much for taking the time to see me today. I appreciate your support of our work in prevention of problems impacting our youth.

Tell your story. Explain your issue and position, your experience and the impact on others.

State your purpose. Let your legislator know the bill or general issue you are meeting with him or her about and your position (e.g., opposition to budget cuts). You should focus on a single issue or a very short set of priorities. Tell your story. Describe why this bill or issue matters to you. Share your experiences as a coalition leader. Your story should make a point that will support your request for action or a position. Address the public good. Describe the impact of the bill or issue more broadly on your community. Mention how the bill or issue will address a challenge and/or benefit others. Add a fact. If you like, add a fact that will help support your cause.

Wrap it up. Request a specific action or position on a bill or issue.

Make your “ask.” Describe what action or position you want your legislator to take. This should be specific and refer to proposed or pending legislation, vote or decision, if applicable. Give the bill number for the legislation, if possible. Otherwise, ask them to show leadership on your issue and to make it a legislative priority. Make sure you don’t do all the talking. Give your legislator opportunities to ask questions or state his or her opinion. Your legislator will appreciate the chance to be heard and you can learn a lot by listening. If your legislator expresses disagreement with your position, politely address any questions or concerns, make your point and move on. If you do not have an answer to a question, say so, and promise to get back to your legislator with an answer. Remember, you are meeting with your legislator to inform him or her about your issue and encouraging his or her support. It is not your job to make decisions or offer solutions on problems your legislator may bring up. Optional: Make the close. If your legislator did not give a definite response to your request, ask how he or she will vote on your issue. If your legislator is undecided or evasive, let him or her know you will follow-up with them. Optional: Leave a fact sheet. If you can, leave a fact sheet or leave-behind a summary of your request. This will remind your legislator of your key points and show that you are well-prepared. Thank your legislator. Once again, let your legislator know you appreciate his or her time and attention (and support, if applicable). Offer to be a resource. If he or she is unfamiliar with the issues you presented, make sure they know they can count on you as a resource in the future.

Follow-up

Send a thank you note. A hand-written thank you note is not only polite, but will leave a very positive impression and allows you to gently repeat your ask. If applicable: Follow through on a request. If your legislator requested additional information or facts about your issue, be sure to follow-up as soon as possible. You do not need to have all the answers. You can contact local mental health advocacy organizations to assist with an appropriate response. If applicable: Check back on your legislator's position. If you indicated that you would check back to get a response regarding your legislator’s position, make sure you do so. Write, call or email in a week or two after your meeting to follow-up. Handout 6

Return on Investment: Evidence-Based Options to Improve Statewide Outcomes Report

The 2009 Washington Legislature directed the Institute to “calculate the return on investment to taxpayers from evidence-based prevention and intervention programs and policies.” The Legislature instructed the Institute to produce “a comprehensive list of programs and policies that improve . . . outcomes for children and adults in Washington and result in more cost-efficient use of public resources.” The Legislature authorized the Institute to receive outside funding for this project; the MacArthur Foundation supported 80 percent of the work and the Legislature funded the other 20 percent. This main report summarizes our findings. Readers can download the two detailed technical appendices for in depth results and statistical methods.

To access this report please go to the following link: http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/pub.asp?docid=11-07-1201 Handout 7

State Legislative Process

Pennsylvania's General Assembly is made up of a 203-member House of Representatives and a 50-member Senate.

Any member of the legislature can introduce a bill. Upon introduction, the measure is assigned a number and referred to the appropriate committee. Both the House and Senate have committees, which focus on specific issues and serve as the General Assembly's legislative workshop.

Bills introduced by House members go to House committees; bills introduced by Senate members go to Senate committees.

The committee chairman, who represents the chamber's majority party, decides what bills the committee considers. This is a tremendous power for a legislator. The committees comprise several members of both parties, but the majority party has more voting members. Bills brought before the committee are subject to review and debate. The committee may hold hearings and solicit testimony; members may propose amendments.

Not every bill gets a vote. There are four potential outcomes:

The bill is approved as submitted and sent to the full House or Senate for consideration. The bill is amended, usually to hasten passage or as part of a compromise, and sent to the full House or Senate for consideration. The bill is tabled or set aside, rendering it inactive. The bill is voted down or never reported from committee, nullifying it.

Approved bills go immediately to the chamber of origin's Appropriations Committee, where a fiscal note is prepared to detail the financial impact of the legislation. Bills in this committee face the same four outcomes, as noted above.

A bill must clear many hurdles before it becomes a law. After committee approval, the House or Senate, where the measure is being debated, must consider the bill on three separate days before voting. On the first day, the bill is read on the chamber floor to alert members that the committee has reported the bill as originally introduced or amended. No amendments are offered, no debate is held and no votes are taken. Amendments to the bill may be offered on the second or third reading, after which a vote can be taken. All legislators who are present in the chamber must vote on the bill; abstentions are not allowed.

If the bill is approved by the full chamber, it is sent to the other chamber for consideration, where it must run through an identical committee structure and voting process. For example, a House bill that wins committee approval and is passed by the full House then moves to the Senate. After passage in the House, the appropriate Senate committees must approve the measure and send it to the full Senate for voting. If the Senate changes the bill, it must go back to the House for concurrence in those changes. Identical versions of the bill must be passed by both the House and Senate before it can be sent to the Governor, who can sign it into law or veto it. A bill also can become law if it is sent to the Governor, and he fails to sign it or veto it before a prescribed deadline.

The whole process can takes months. Bills not enacted during the two-year session must be reintroduced the following session and run through the same process again from the beginning. Handout 8

D0 You Know?......

WHAT WERE THE PRIMARY REASONS FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT? Our Founding Fathers expressed their reasons in the preamble to the Constitution: to "form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity..."

WHAT IS A REPUBLIC? A republic is that form of government in which the administration of affairs is open to all the citizens. It is characterized by a constitutional form of government, especially a democratic one. A republican government is a government by representatives chosen by the people.

WHAT IS A DEMOCRACY? A democracy is government by the people. In a democracy, supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them, either directly (absolute or pure democracy) or through elected representatives (representative democracy).

IS THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT A REPUBLIC OR A DEMOCRACY? It is both. The United States is a republic because we have a constitution, an elected leader rather than a monarch, and our citizens all work freely and equally toward the same cause - the preservation and operation of the nation.The United States government is also a representative democracy. An absolute or pure democracy would be unwieldy because of the country's large area and population.

WHAT IS THE "SUPREME LAW OF THE LAND"? The United States Constitution, federal laws, and treaties are considered to be the "supreme law of the land." The judges of every state are bound by it, regardless of anything contrary in individual state constitutions or laws.

WHAT IS A COMMONWEALTH? In reference to Pennsylvania, the word "commonwealth" is synonymous with "state." The term is of English derivation and implies a special devotion of the government to the common "weal," or the welfare of its citizens. The colony of William Penn was known as the Quaker Commonwealth, and records show that those who framed the Pennsylvania constitutions from 1776 through 1878 continued this terminology. Interestingly, the state seal of Pennsylvania does not use the term, but as a matter of tradition it is the legal designation used in referring to the state.

HOW MANY COMMONWEALTHS ARE THERE IN THE UNITED STATES? Four. In addition to Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Massachusetts, and Virginia are also considered commonwealths.

WHY IS PENNSYLVANIA CALLED THE "KEYSTONE STATE"? This nickname for Pennsylvania first appeared shortly after the American Revolution and was in common usage by the early 1800s. It is believed that the original attribution referred to Pennsylvania's central geographic location among the Atlantic seaboard states. Modern use of the designation is justified in view of Pennsylvania's key position in the economic, social, and political development of the United States.

HAS HARRISBURG ALWAYS BEEN THE CAPITAL OF PENNSYLVANIA? No. The Pennsylvania Colony established its first capital in 1643 at Tinicum Island in the Delaware River. William Penn arrived in 1682 and convened the first General Assembly in Chester, which remained the capital until the following year. Philadelphia became the state capital when the Provincial Government was established there in 1683. Lancaster became the capital on the first Monday of November 1799 and remained so until Harrisburg was designated as the seat of state government in 1812.

HOW CAN THE LOCATION OF THE STATE CAPITAL BE CHANGED? The Constitution says that a law that would change the location of Pennsylvania's state capital would only be valid when voted on and approved by voters in a general election (see Article III, Section 28).

WHAT PENNSYLVANIA CITIES WERE ONCE THE CAPITAL OF THIS COUNTRY? Philadelphia, Lancaster, and York. During the Revolutionary War, when General Washington was defeated by General Howe at Brandywine, it was decided to move the capital from Philadelphia because of the fear of attack. Congress adjourned and met in Lancaster for one day before moving to York. York remained the capital during the British occupation of Philadelphia from 1777 until 1778.The seat of government was transferred briefly to New York City and then returned to Philadelphia until 1800, when it moved to Washington, D.C.

WHO WAS THE ONLY NATIVE PENNSYLVANIAN TO BE ELECTED PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES? James Buchanan, born in Cove Cap, Franklin County, in 1791, was elected President of the United States in 1856. Handout 9

Working With the Media: Some Useful Tips

Be responsive, respect deadlines – missed opportunity

Be on time for the interview

Establish yourself as THE expert - no one knows this stuff better than you

Don’t be afraid to correct misinformation

Repeat your points – consistently stay on message

Collect your thoughts before responding – take a moment to frame your answers

Stick to facts and data - DO NOT speculate or editorialize; if you don’t have an answer, just say so

Provide a one-page fact sheet supporting your position

NOTHING is ‘off the record’

Don’t be defensive, argumentative, adversarial or critical of either the reporter or anyone else

Don’t use acronyms – ‘PCCD’, ‘DPW’, ‘ODAP’, ‘JCJC’ Don’t provide opinions that are not based on facts

Don’t send volumes of research or reports Handout 10

Communications & Legislative Advocacy Strategic Planning: Media

Your location (county, city, legislative district): ______; ______; ______

Your major local media outlets (print and television):

Do you have any local media contacts? (name(s)):

______; ______;

Are other ‘experts’ (locally or elsewhere) available to talk to the media who can support your position? (name(s)):

Can you provide an opportunity for your local elected official(s) to be credited for supporting your efforts (describe)? Description of local efforts - specific outcomes and accomplishments - and key talking points (list at least 3):

Handout 11

The Strategy Chart

GOALS ORGANIZATIONAL CONSTITUENCY TARGETS TACTICS

1. media releases & press stories Who has the Long term What resources can you Who cares about the power and 2. multiple (12-18 months) put into the advocacy issue? influence to give connections with effort? you want you policy makers want? 3. public events

4.

1. Capitol Hill Day

Intermediate Who are 2. (8-12 months) How will you build the How will you secondary targets advocacy effort? become organized? of your efforts? 3.

4. 1. Organize What and who are Short term Identify potential potential barriers to 2 Meet your (present – 8 problems you might your efforts? legislator months) encounter along the way? 3. Letters to the Do they have power Editor, develop and influence? press kit & seek coverage

* adapted from Midwest Academy ‘Organizing for Social Change’