Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures

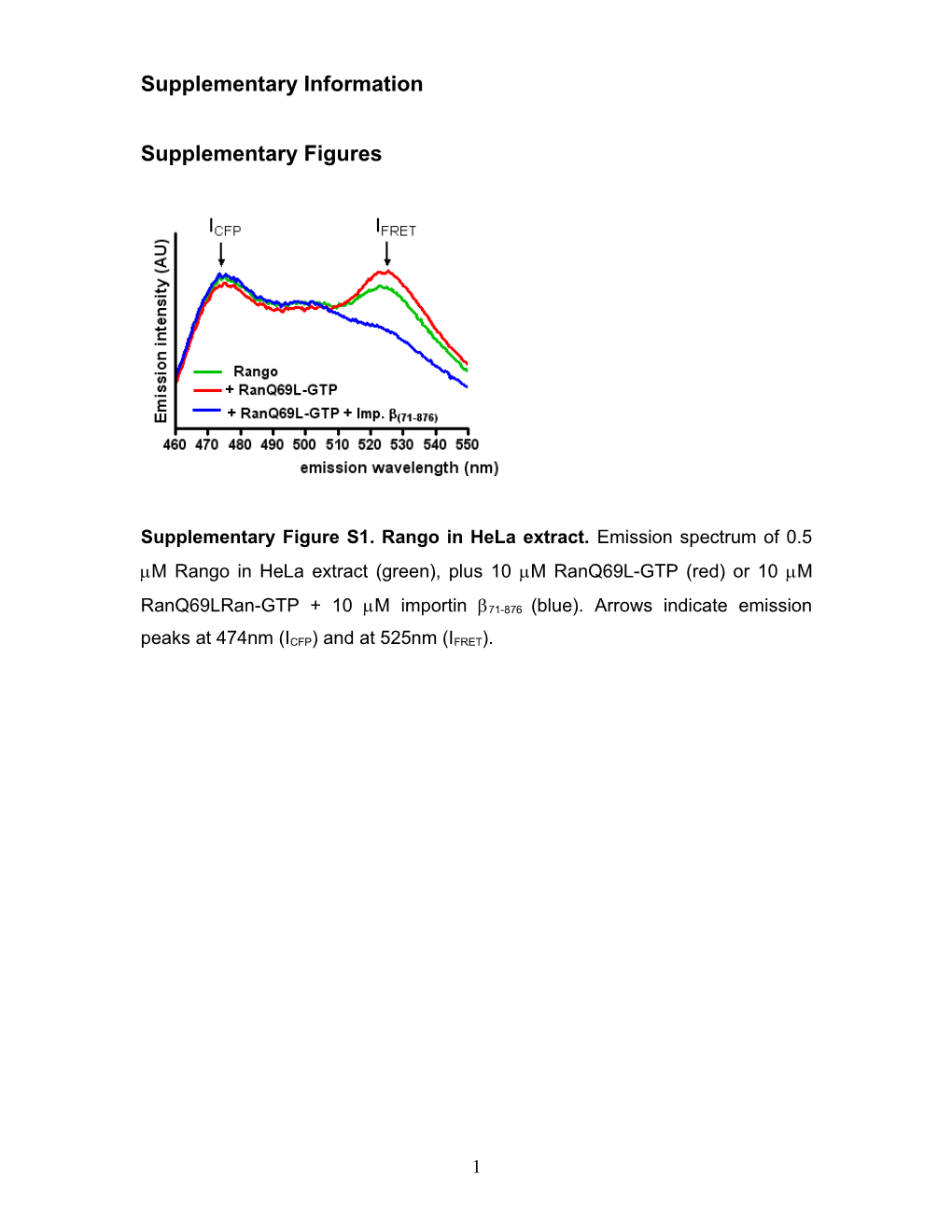

Supplementary Figure S1. Rango in HeLa extract. Emission spectrum of 0.5 M Rango in HeLa extract (green), plus 10 M RanQ69L-GTP (red) or 10 M

RanQ69LRan-GTP + 10 M importin 71-876 (blue). Arrows indicate emission peaks at 474nm (ICFP) and at 525nm (IFRET).

1 Supplementary Figure S2. Estimation of the apparent dissociation constant for Rango-importin . Increasing amounts of importin were added to 6 nM Rango and the IFRET/ICFP ratio was determined by spectrofluorimetry. Half- maximal binding was observed at about 2 nM importin .

2 Supplementary Figure S3. Disruption of the Ran-importin interaction in vivo is reported by the Rango fluorescence lifetime signal. The upper panel shows the same cells displayed in Fig. 1c together with an image of the fluorescent dextran tracer in the rhodamine channel to indicate the Rango- expressing cell (left) that was coinjected with importin 71-876 (420 M in the needle). The microinjection of importin 71-876 resulted in a strong increase of Rango fluorescence lifetime =2.44 ± 0.03 ns N=4) indicative of nearly complete binding of homologous endogenous cargo. In the lower panel, a mitotic HeLa cell expressing Rango was injected with rhodamine-tubulin and RanQ69L (420 M), abolishing the mitotic Rango gradient =2.21 ± 0.03 ns, N=5). Bar, 20 m.

3 Supplementary Figure S4. Comparison of Rango FRET signal in mitotic cells and interphase nuclei by acceptor bleach. Rango FRET signal was measured in interphase HeLa, in mitotic HeLa and BHK cells (averaged cytoplasmic + chromatin signal), and in HeLa interphase cells microinjected with

Rango and importin 71-876 as indicated. The ratio of Cerulean CFP fluorescence recovery after / before YFP photobleaching was used as a measure of the Rango FRET signal. Boxes include the 25th to 75th percentile. In addition, the median is represented by a horizontal line and minimal and maximal values indicated by the error bars. The Rango FRET signal is similar in the cytoplasm of mitotic HeLa and BHK cells (P> 0.05), but smaller than the Rango FRET signal in interphase HeLa nuclei (P<0.01), and larger than in nuclei of HeLa cells coinjected with

Rango and importin 71-876 (P<0.01). The statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests.

4 Supplementary Figure S5. Fractional occupancy detected by FLIM in mitotic HeLa cells. The scatter plot displays the Rango fractional occupancy in individual mitotic cells (N=36) in the chromatin region (red) and in the cytoplasm (N=36) (blue). The difference between cytoplasmic and perichromatin fractional occupancy in individual cells is displayed in orange (N=36, “gradient”). The horizontal bars in plots represent means +/- standard deviation. We excluded from the analysis of the Rango gradient additional 10 cells in which the difference between chromatin and cytoplasmic donor was found to be lower than the typical pixel-to-pixel noise in our conditions (0.04ns). If this data were included, the average Rango occupancy in the chromatin changes from 18 +/- 9% (N=36) to 18 +/- 10% (N=46) and from 31 +/- 12% (N=36) to 29 +/- 13% (N=46) in the cytoplasm.

5 IYFP IFRET/ICFP ICFP after/before YFP bleach

Supplementary Figure S6. The Rango gradient detected by confocal microscopy in mitotic Hela cells. Rango is excluded from mitotic chromatin, as shown in the YFP fluorescence image (left). Pseudocolor images of the IFRET/ICFP ratio (center) and ratio of ICFP after and before YFP photobleaching (right) demonstrate a significant increase in importin free Rango in the perichromatin area. Linescans below the ratio images display the signal averaged over 5 m wide area in linear section across cells in the ratio images, marked with a line. Bar, 10 m.

6 Supplementary Figure S7. Rango FRET gradient in mitotic cells. The Rango FRET signal was measured by the acceptor bleach method in mitotic cells transfected with Rango, and the Rango gradient was calculated as a difference between the average signal over the chromatin area vs. cytoplasm in individual cells (bar height = mean +/- standard deviation). Boxes include the 25th to 75th percentile, with the median represented by a horizontal line and minimal and maximal values indicated by shorter horizontal lines. Already at the permissive temperature (tsBN2 33oC) the average Rango gradient in tsBN2 cells was smaller than in BHK21 cells (P<0.05) and in HeLa cells (P<0.01) indicative of a decreased activity of RCC1 carrying temperature sensitive mutation. However, treatment with the non-permissive temperature (tsBN2 40oC) abolished the gradient, as indicated by a significant difference between tsBN2 at permissive and non-permissive temperature (P<0.05). Statistical analysis was performed with one way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

7 Supplementary Figure S8. Computational model of mitotic cytoplasm We built a computational model of a minimal Ran system1 coupled to the minimal set of nuclear transport receptors, including importin and Rango, using Virtual Cell2, 3. This model applies kinetic parameters as described by Görlich et al. (2003) 1 and Riddick and Macara (2005) 4. As expected, in initial simulations we found that the relative concentrations of transport receptors and their cargoes, have a large effect on the resulting Rango fractional occupancy at equilibrium. To compare the response of this model system to the experimental perturbations in the extracts (i.e. the addition of importin and RanQ69L), we set the initial reactant conditions to reflect the measured Rango fractional occupancy at equilibrium in mitotic Xenopus egg extracts.

Concentrations of Ran-transport system components used in the model (in M)

RanGTP 3 RanBP1 2 RanGDP 3 NTF2 0.6 GDP 1.6 Importin 3 GTP 470 Importin cargos 8 RCC1 0.25 Rango 2 RanGAP 0.4 Importin -like 5 transport receptors

Under these conditions, the response of this minimal system to importin and RanQ69L is qualitatively similar to our in vitro observations (Fig. 3c). This suggests that the response of a localized importin cargo release in vivo can be quantitatively described in a simple mathematical model.

The models can be accessed at the published models webpage of the Virtual Cell project (http://www.nrcam.uchc.edu/ User: Pralle, password: Ran ).

8 a b c

RanQ69L, 420 M importin , 80 M importin 71-876, 25 M 40 min 40 min 105 min

Supplementary Fig S9. Examples of phenotypes induced by microinjection of HeLa cells with Ran system components. Mitotic HeLa cells were microinjected, allowed to recover and then fixed and stained for tubulin and DNA. The concentration of individual proteins in the needle, and time of recovery after injection are indicated below the figures. a, Ectopic microtubule asters connecting to chromatin observed in a prophase cell microinjected with RanQ69L. b, Prophase reversal: example of a HeLa cell that was microinjected in prophase-to- metaphase state was found to revert to an interphase-like microtubule pattern with decondensing chromatin. c, HeLa cell arrested in a prolonged prophase state following microinjection of a relatively low concentration of importin 71-876.). Scale bar, 10 m

9 Supplementary Table

prophase prophase spindle Protein M reversal stall / ectopic pole % normal N defect asters defect BSA 550 3 0 0 1 70 37 RanQ69L 420 8 14 10 9 29 62

Imp. 66-529 310 3 18 0 4 52 56 40 0 3 0 0 77 13

Imp.71-876 180 4 9 0 0 30 23 420 5 19 0 0 58 63 25 2 2 0 5 54 33 Importin 80 2 8 0 1 46 26 410 6 9 0 7 22 31

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of phenotypes induced by HeLa cell microinjections. Prophase and metaphase HeLa cells were injected with protein

o solutions as indicated and incubated at 37 C, 5% CO2 before being fixed, stained and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Coinjected fluorescent dextran was used as a marker to locate the injected cells. All treatments contain data from slides fixed at time intervals that varied between 20-105 min. While this allowed us to qualitatively examine a wider spectrum of possible phenotypes during mitosis, a quantitative comparison of defect penetrance is limited. Highlighted in red are the most prominent mitotic phenotypes induced by individual microinjected proteins. Some cells that were injected in prophase-to- metaphase state were found with interphase-like microtubules and a single mass of decondensing chromatin, indicative of aborted mitosis (Supplementary Fig. S9b). While such a “prophase reversal” phenotype was induced by all microinjections, it was particularly frequent in cell injected with large concentration of wt importin (19%). This indicates the presence of a checkpoint-like mechanism that is capable to revert progression of mitosis in cells exposed to a variety of destabilizing insults, including disruptions of Ran- importin regulation. Prophase cells with large monoastral MT arrays (Figure

4, cell injected with Importin 66-529) and all cells that were found in a prophase state after more than 50 min of recovery (Supplementary Fig. S9c) are included in “prophase stall / defect“ category. Cells with “ectopic asters” were those with

10 relatively small cytoplasmic microtubule asters that in some cases partially interacted with chromatin (Fig. 4, cell injected with RanQ69L, Supplementary Fig. S9a). The category “spindle pole defect” includes cells with more robust, supernumerary spindle pole–like microtubule structures associating with the chromatin (Fig 4, cell injected with full length importin ), and cells with apparently split, duplicated or malformed spindle poles.

Supplementary methods

Cloning and protein expression

To create a His6-tagged Rango E.coli expression plasmid (pKW1648), the importin -binding domain of Snurportin15 (1-65) was inserted in frame between EYFP (Clontech) and Cerulean6 cloned into pRSET-A (Qiagen). For expression in tissue culture cells, the pKW1648 open reading frame was transferred into pSG8, removing the N-terminal His6 tag (pKW1608). The pSG8 plasmid for k- Rango expression in cells (pKW1844) was produced by inserting the satellite DNA binding domain of human Cenp-B7, at the 3’ of pKW1608 via BamH1 site. The double protein A (ZZ) tagged-RanQ69L E.coli expression clone was obtained by transferring ZZ-RanQ69L8 from pQE32 into pRSET-A (pKW1234). The RBD-Cerulean clone for expression of Cerulean control protein in cells (pKW1705) contains the Ran-binding-domain (RBD) of Yrb19 followed by Cerulean.

Wild type Ran, zzRanQ69L, importin and importin 71-976 were expressed as described9. High yield of Rango proteins was obtained from BL21- DE3 cells induced overnight at room temperature. The proteins were isolated from French press lysates on NiNTA beads (Qiagen), dialyzed in XB (50 mM sucrose, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.7), purified using a Superose 6 column (Pharmacia) in XB, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80oC. Wheat germ agglutinin was purchased from Sigma, rhodamine-tubulin from Cytoskeleton, and Lysine-fixable 75 kD Dextran-FITC and Dextran-Rhodamine from Molecular Probes.

11 Spectrophotometry Emission spectra were analyzed with a Fluorolog 2 spectrofluorimeter controlled by Datamax 2.2 (Jobin Yvon Spex) and the Grams 3.04 II software package (Galactic Industries, Salem, NH). Excitation wavelength, and excitation (1.2-2.0 nm) and emission slits (2 or 5 nm) were set individually to minimize sample-specific background and prevent saturation. Rango in Xenopus extracts (Fig. 3c) was excited at 410 nm; excitation at 435 nm was used in Fig. 1b,c. A blank was subtracted from all emission spectra except Fig. 1b. Rango in HeLa extract (Supplementary Fig. 1) and in buffer (Supplementary Fig 2) was excited at 410 nm and a corresponding blank was subtracted from the emission spectra.

Estimate of the importin free Rango fraction in X. laevis egg extract

We assumed that the IFRET/ICFP ratio measured at saturating concentrations of RanQ69L (25 M, data not shown) corresponds to a concentration of free Rango approaching 100%, and the IFRET/ICFP measured at saturating concentration of importin (20 M) corresponds to near complete Rango binding. Using this assumption, we normalized IFRET/ICFP values measured in extract (Fig. 3c), and

IFRET/ICFP values measured in vitro (Fig. 1c) to a 0-1 scale. Next, we used the

IFRET/ICFP values measured in the extract to determine the closest corresponding Rango fractional occupancy determined in in vitro.

Microinjection

Cells were seeded at 25% confluency on glass coverslips 2-3 days prior to microinjection. Proteins were diluted in XB or IB buffer (100 mM potassium glutamate, 40 mM citric acid, pH 7.4), and centrifuged 5 min at 100 000xG prior to microinjection, using an Olympus IX71 microscope equipped with a FemtoJet microinjector (Eppendorf).

Immunofluorescence Microinjected HeLa cells were fixed in 0.05% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde (freshly prepared) in PHEM (60 mM Pipes, 25 mM Hepes, pH

12 o 6.9, 10 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgSO4) for 15 min at 37 C, followed by 5 min treatment with fresh 0.5% (w/v) NaBH4 in PHEM and 20 min block in 100 mM Glycine made in 6% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 0.02% saponin, PHEM, pH 7.0. The cover slips were incubated with anti -tubulin mouse monoclonal antibody E7 (1:350; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa) followed by Donkey anti mouse IgG- Rhodamine or Donkey anti-mouse IgG-FITC (Jackson Laboratories). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 dye (Sigma). Samples were mounted with Anti-Fade Gold (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen).

Live cell imaging During all live cell imaging experiments, cells were maintained at 30 oC in a temperature controlled imaging chamber (Warner instruments). For epifluorescence and FLIM measurement, cells were kept in Dulbecco’s PBS (Gibco, Invitrogen) supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco, Invitrogen). During acceptor bleach experiments, cells were in Opti-MEM, 4% FBS (Gibco, Invitrogen).

Epifluorescence Live epifluorescence ratio imaging in Fig. 3a was performed with a Nikon E600 microscope equipped with CFP-YFP FRET filter sets (Chroma) and Hamamatsu C4742-98 CCD camera as described previously9, using Nikon Fluor 60x/1.00W water immersion lens (Nikon) for cells, and 40x/0.75 Nikon PlanFluor lens for egg extract samples. Exposure time was 0.5-4 s and always identical for YFP, CFP an FRET channels within a given sample. Image processing was performed with Metamorph (Molecular Devices). The pixel alignment of the IYFP,

ICFP, and IFRET images was verified and adjusted, the background taken outside the cells subtracted and IFRET/ICFP and ICFP/IYFP ratio computed. The 60x oil immersion lens on Nikon E600 microscope was used to count rhodamine labeled microtubule asters in Fig. 3c. Live samples of rhodamine labeled microtubules in Xenopus egg extracts (Fig. 3c) were examined and photographed using 60x oil immersion lens and all fixed immunofluorescence samples using 100/1.30x oil immersion lens, both on Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with Hamamatsu CA 742-98 CCD camera.

13 Confocal microscopy Confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM 510 META laser scanning confocal microscope. Cerulean was excited by the 458 nm Argon laser line and emission was simultaneously acquired at 462-505 nm (ICFP) and 537-569 nm (IFRET) by the META detector. YFP was excited by the 514 nm Argon laser line, acquiring IYFP by 526-601 nm META detector. Four 12-bit image sets of

256x256 pixels were acquired (7.58 s per image) in each channel (IYFP, ICFP +

IFRET) prior to bleaching YFP by scanning with the 514 nm laser at full power for 100-200 iterations (20-30 s), followed by acquisition of an additional three sets of images in all channels. As Rango is mostly excluded from condensed mitotic chromatin, we used an 8 M optical slice in all experiments to obtain enough signal. FRET efficiency was calculated as ratio of ICFP signal in the first image following bleaching, and the ICFP signal in the image preceding the bleach. In mitotic cells, the FRET efficiency was determined from an area covering the entire cell, an area within the chromatin region, and two cytoplasmic regions located approximately 70% distance between chromatin and the plasma membrane. As a measure of the mitotic Rango gradient, we calculated the difference between FRET efficiency within chromatin area and cytoplasmic average.

Fluorescence lifetime microscopy Datasets of spatially resolved, time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) were acquired on an inverted Zeiss LSM510 Axiovert 200M microscope with a NeoFLUAR 40 /1.3 NA oil-immersion immersion objective lens, equipped with a TCSPC controller (Becker & Hickl SPC-730 card). Samples were excited by 6 W, 435 nm generated by frequency-doubling 870nm pulses from a mode- locked Ti:Sapphire laser (Tsunami, SpectraPhysics, 120-150 fs pulse width, 80 MHz repetition rate). One photon excitation of Cerulean at 435 nm was preferred over two-photon excitation because it provided less direct excitation of YFP. The emission light was filtered with a 480 nm bandpass filter (480BP40, Chroma) and detected by a PMC-100 photomultiplier (Becker & Hickl) mounted to the fiber-out port of the confocal scanhead. Recording conditions were chosen to achieve

14 approximately 105 counts per second, and images of 64 64 pixels (1024 time bins/pixel) were averaged over 2-4 minutes. For the calibration curve (Fig. 1), the fluorescence lifetime of a 1 M solution of Rango in PBS, 0.03% Tween 20 was measured over 1 minute while scanning the laser in an area of 20 20 m 30 m above the coverslip surface at 23oC and 30oC. Off-line data analysis was done using pixel-based fitting software (SPCImage, Becker & Hickl), assuming single exponential incomplete decay during the 12.5 ns interval between laser pulses.

Xenopus laevis egg extracts

Assays for the detection of the Rango IFRET/ICFP signal during mitotic spindle assembly in X. laevis egg extracts were performed as described previously9 with rhodamine-tubulin and 2 M Rango in the extract instead of YIC. For the experiment in Fig. 3c, mitotic egg extract containing 1 M Rango and 15 g/ml rhodamine-tubulin was divided into 57 l aliquots. Samples were then supplemented with 3 l zzRanQ69L or importin , respectively, to achieve concentrations indicated in Fig. 3c. Control samples received 3 l buffer only. Samples were then transferred from ice to a 21oC water bath and Rango emission at 435 nm excitation was continuously monitored until a stable I FRET/ICFP ratio was reached (60-90 min). At the end of the scans (90-120 min), rhodamine- labeled microtubule structures were examined and photographed live in 2-3 aliquots of samples. To quantify the aster promoting activity in the samples, after the last scan, 30 l extract samples were fixed in freshly prepared 10% glycerol, 4% formaldehyde, 0.1% glutaraldehyde, PHEM. Fixed samples were then spun on 12 mm round coverslips as described8, fixed in -20oC methanol (10 min), rinsed with PHEM and mounted on microscope slides. The aster promoting activity, defined as an average number of microtubule asters highlighted by incorporated rhodamine-tubulin, was counted in 30 randomly selected visual fields (600x total magnification).

HeLa cell extracts

15 HeLa S3 cells grown in suspension culture were washed with PBS by centrifugation, pelleted and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The frozen pellet (1 ml) was supplemented with 700 l M/PBS buffer (120 mM Na -glycerophosphate, 60 mM EGTA, 22.5 mM MgCl2, 72 mM NaCl, 1.3 mM KCl , 5 mM Na2HPO4. 8.5 mM

KH2PO4, pH 7.4.) containing 20 mg/ml each leupeptin, pepstatin and chymostatin, and 1 mM PMSF. The tube was placed on ice and the liquid above the pellet sonicated at 0.5 W using a microtip (Virsonic sonicator, The Virtis Company Inc., Gardiner, NY) until the pellet became homogenized (about 5 min). The sonicated lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 10 min and used immediately.

Rango – importin dissociation constant Aliquots of 40 nM Rango in PBS were diluted with increasing concentrations of importin in PBS to achieve a final concentration of 6 nM

Rango and 0-40 nM importin . IFRET/ICFP ratios in samples were measured at 25oC against a PBS blank in two samples (2-3 scans each) from each dilution aliquot. The IFRET/ICFP values were plotted against the importin concentration and data were fitted with a down to bottom curve, standard slope using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA). The Rango-importin dissociation constant was determined using the importin concentration at 50% amplitude of Rango IFRET/ICFP curve.

Supplementary references 1. Gorlich, D., Seewald, M. J. & Ribbeck, K. Characterization of Ran-driven cargo transport and the RanGTPase system by kinetic measurements and computer simulation. Embo J 22, 1088-100 (2003). 2. Schaff, J. C., Slepchenko, B. M. & Loew, L. M. Physiological modeling with virtual cell framework. Methods Enzymol 321, 1-23 (2000). 3. Smith, A. E., Slepchenko, B. M., Schaff, J. C., Loew, L. M. & Macara, I. G. Systems analysis of Ran transport. Science 295, 488-91 (2002). 4. Riddick, G. & Macara, I. G. A systems analysis of importin-a-b mediated nuclear protein import. J Cell Biol 168, 1027-38 (2005). 5. Huber, J., Dickmanns, A. & Luhrmann, R. The importin-beta binding domain of snurportin1 is responsible for the Ran- and energy-independent nuclear import of spliceosomal U snRNPs in vitro. J Cell Biol 156, 467-79 (2002).

16 6. Rizzo, M. A., Springer, G. H., Granada, B. & Piston, D. W. An improved cyan fluorescent protein variant useful for FRET. Nat Biotechnol 22, 445-9 (2004). 7. Shelby, R. D., Hahn, K. M. & Sullivan, K. F. Dynamic elastic behavior of alpha- satellite DNA domains visualized in situ in living human cells. J Cell Biol 135, 545-57 (1996). 8. Nachury, M. V. et al. Importin beta is a mitotic target of the small GTPase Ran in spindle assembly. Cell 104, 95-106 (2001). 9. Kalab, P., Weis, K. & Heald, R. Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science 295, 2452-6 (2002).

17