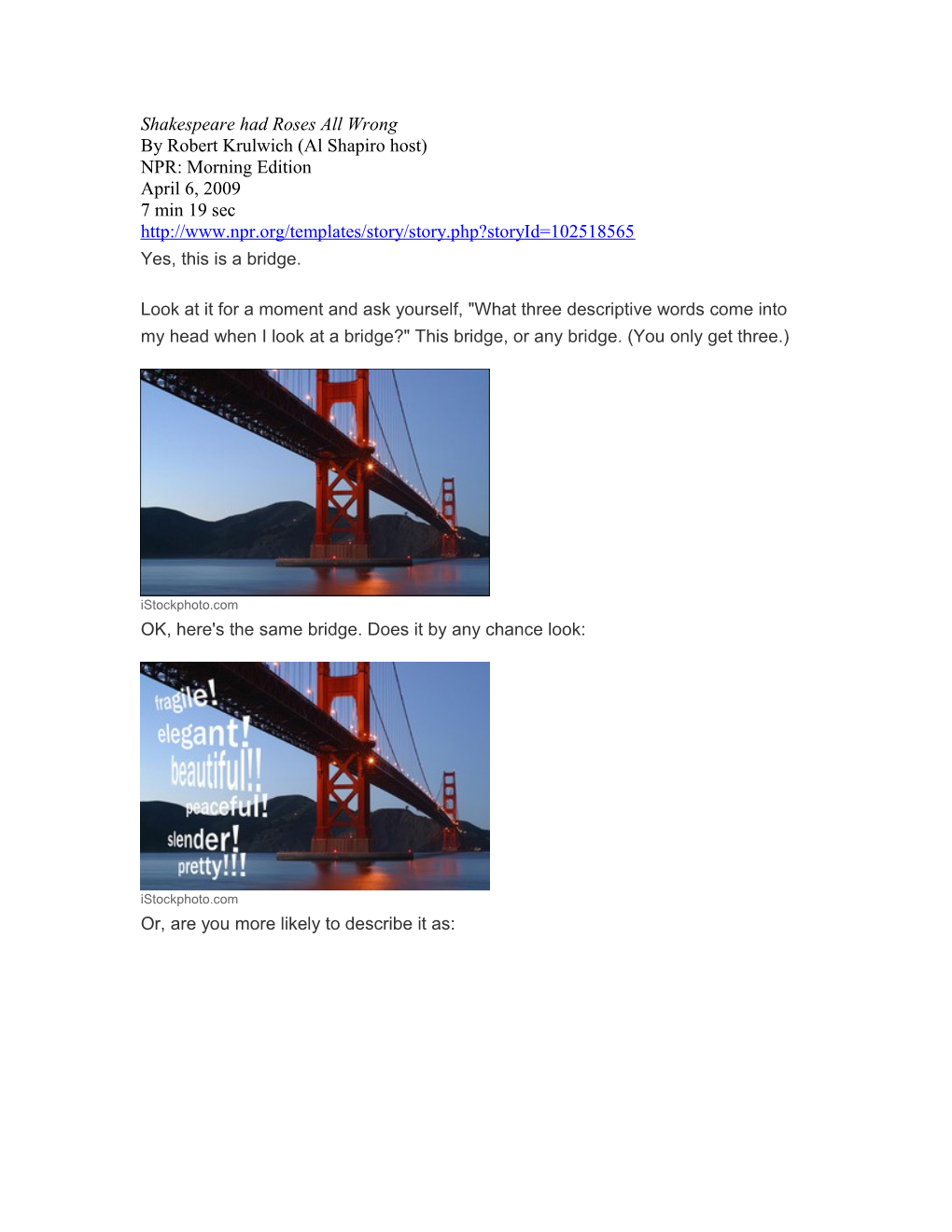

Shakespeare had Roses All Wrong By Robert Krulwich (Al Shapiro host) NPR: Morning Edition April 6, 2009 7 min 19 sec http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=102518565 Yes, this is a bridge.

Look at it for a moment and ask yourself, "What three descriptive words come into my head when I look at a bridge?" This bridge, or any bridge. (You only get three.)

iStockphoto.com OK, here's the same bridge. Does it by any chance look:

iStockphoto.com Or, are you more likely to describe it as: iStockphoto.com The first batch of words — such as beautiful, elegant, slender — were those used most often by a group of German speakers participating in an experiment by Lera Boroditsky, an assistant psychology professor at Stanford University.

She told the group to describe the image that came to mind when they were shown the word, "bridge."

The second batch of words — such as strong, sturdy, towering — were most often chosen by people whose first language is Spanish.

iStockphoto.com What explains the difference?

Boroditsky proposes that because the word for "bridge" in German — die brucke — is a feminine noun, and the word for "bridge" in Spanish — el puente — is a masculine noun, native speakers unconsciously give nouns the characteristics of their grammatical gender. "Does treating chairs as masculine and beds as feminine in the grammar make Russian speakers think of chairs as being more like men and beds as more like women in some way?" she asks in a recent essay. "It turns out that it does. In one study, we asked German and Spanish speakers to describe objects having opposite gender assignment in those two languages. The descriptions they gave differed in a way predicted by grammatical gender."

When asked to describe a "key" — a word that is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish — German speakers were more likely to use words such as "hard," "heavy," "jagged," "metal," "serrated" and "useful." Spanish speakers were more likely to say "golden," "intricate," "little," "lovely," "shiny" and "tiny."

Boroditsky created a pretend language based on her research — called "Gumbuzi" — replete with its own list of male and female nouns. Students drilled in the language were then shown bridges and tables and chairs to see if they began to characterize these things with their newly minted genders. And it turns out well, we don't want to spoil this for you, so if you want to listen to ourMorning Edition piece, stop reading here.

(And click the red listen button in the upper left of this page.)

OK. Ready for the answer? They did.

Boroditsky suggests that the grammar we learn from our parents, whether we realize it or not, affects our sensual experience of the world. Spaniards and Germans can see the same things, wear the same cloths, eat the same foods and use the same machines. But deep down, they are having very different feelings about the world about them.

William Shakespeare may have said (through Juliet's lips): "a rose by any other name would smell as sweet," but Boroditsky thinks Shakespeare was wrong. Words, and classifications of words in different languages, do matter, she thinks. Kean Collection/Getty Images (In case you don't speak Gumbuzi, "oos huff" means "a rose.")

In our broadcast, Boroditsky does an experiment — two bags, both filled with rose petals, but with different labels — that proves the Bard wrong. Or so she says.

Boroditsky's essay on this subject, "How Does Our Language Shape the Way We Think?" is part of the soon-to-be published anthology What's Next?" (Vintage Books, June 2009).

Related NPR Stories

What's The Big Idea? Start With Language Nov. 12, 2008 Darwin's Very Bad Day: 'Oops, We Just Ate It!' Feb. 24, 2009 A Way With Words: Language And Human Nature Sep. 14, 2007 Would Life Be Better If We All Spoke Shakespeare? April 26, 2007

TRANSCRIPT: Heard on Morning Edition

April 6, 2009 - ARI SHAPIRO, host:

This next story, from our science correspondent Robert Krulwich, starts with a language exercise.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Okay, now here's what we're going to do. We're going to ask a German speaker?

Unidentified Woman (German Speaker): Guten tag.

KRULWICH: ?and a Spanish speaker? Unidentified Man (Spanish Speaker): (Foreign language spoken)

KRULWICH: ?and we'll show each of you some simple nouns, words on a screen like table, chair, maybe a bridge. If you speak German, what is the word for bridge?

Unidentified Woman: Die brucke.

KRULWICH: Die brucke, which is what kind of a noun?

Unidentified Woman: A feminine noun.

KRULWICH: Okay. So we all know that in many languages, nouns can be either masculine, feminine. In German, again, it's?

Unidentified Woman: Die brucke.

KRULWICH: And in Spanish, the word for bridge is?

Unidentified Man: El Puente.

KRULWICH: Which is which kind, a masculine or a feminine?

Unidentified Man: Masculine, el is always masculine.

KRULWICH: Okay. So the Spanish speakers call bridges by a masculine noun, with German speakers it is?

Unidentified Woman: Feminine noun.

KRULWICH: Okay, now comes the fun part.

At her lab, assistant psychology professor Lera Boroditsky of Stanford University asked a bunch of Spanish speakers and then German speakers to look at simple words on a screen - including, as it happens, the word bridge.

Ms. LERA BORODITSKY (Assistant Psychology Professor, Stanford University): And for each object, we just asked them, give us three adjectives that describe that object.

KRULWICH: Just look at the picture and say whatever comes into your head. Ms. BORODITSKY: What we find is that Spanish and German speakers come up with a very different set of descriptions for things like a bridge.

KRULWICH: For German speakers, where the bridge is feminine, the adjectives that popped up most for them were?

Ms. BORODITSKY: Beautiful, extended, elegant.

KRULWICH: And also fragile and pretty. But for Spanish speakers, when they looked at a bridge, they chose?

Ms. BORODITSKY: Long, strong, thrilling?

KRULWICH: Towering, sturdy, dangerous. So when your word for bridge is a masculine noun?

Ms. BORODITSKY: People start to focus on the more masculine parts.

KRULWICH: What Lera Boroditsky found is that the grammar that you learned from your parents, whether you know it or not, affects your sensual experience of the world. If you're German, you can look at the same bridge as a Spaniard and because of a grammatical difference between masculine and feminine nouns?

Ms. BORODITSKY: You find, wow, their underlying understandings of these things are totally different.

KRULWICH: And it's not just bridges. Germans and Spaniards have different genders for tables and for chairs, for all kinds of nouns.

Ms. BORODITSKY: It's a whole lot of stuff.

KRULWICH: It is. So when you inherit a language?

Ms. BORODITSKY: You're inheriting much more than just how to speak. You're learning a whole cultural system.

KRULWICH: Here's another example. Lera asked some German speakers to look at a toaster.

Unidentified Woman: Der toaster. KRULWICH: That's the German word?

Unidentified Woman: Masculine.

KRULWICH: Okay.

Unidentified Woman: Der.

KRULWICH: So everybody turned on their computers and alongside the picture of the toaster were some suggested names, including the name Patricia.

Ms. BORODITSKY: And we had one German speaker come out in the middle of the experiment and she said, I just wanted to tell you, I think there's something wrong with your computer. I think it's broken. And we said, well, why do you say that? And she said, well, it just told me the toaster's name is Patricia, and I know that can't be true because toasters are male.

KRULWICH: So it's somehow deeply ingrained in her that toasters have this quality.

Ms. BORODITSKY: Yes, and that is how it feels intuitively. You know, as a Russian speaker - I grew up in Russia, and then my parents and I moved to America and I had to, of course, learn English.

KRULWICH: And as Lera became more and more of an English speaker?

Ms. BORODITSKY: I felt like I was thinking in an entirely different way.

KRULWICH: And Lera couldn't help but wonder: Is this just the rules of grammar, masculine and feminine nouns that are creating these differences, or could it be something else?

Ms. BORODITSKY: You know, something in the olive oil that Spanish speakers eat or you know, it could be anything. There are so many differences between German speakers and Spanish speakers. So one way to establish whether it's really language that plays this role is to bring people into the lab and teach them a new language.

KRULWICH: So she invented one.

Ms. BORODITSKY: We have a language called Gumbuzi. KRULWICH: Gumbuzi? What does Gumbuzi sound like?

Ms. BORODITSKY: I don't know, you tell me.

(Soundbite of Gumbuzi)

KRULWICH: Useful phrases in Gumbuzi, part 23 - crossing the bridge.

(Soundbite of Gumbuzi)

KRULWICH: Excuse me, I left my umbrella on your bridge. Now you try.

Ms. BORODITSKY: I see you are very familiar with Gumbuzi, nearly fluent.

KRULWICH: To be fair, I just invented that version of Gumbuzi, how could I not, but back to Lera's version. What she did was, she got a bunch of American students who speak only English - so for them, tables and chairs have no gender; they'd had no experience with masculine or feminine nouns - and for a day, she taught these kids a language that assigned gender arbitrarily to different nouns. So she told them half the nouns will begin with oo - oosabigtruck(ph), big truck; oosachesthair(ph), chest hair; oosaman(ph), a man.

Ms. BORODITSKY: The other half of the things are supative(ph).

KRULWICH: Meaning they begin with su. Supink(ph).

Ms. BORODITSKY: Pink.

KRULWICH: Susoft(ph).

Ms. BORODITSKY: Soft.

KRULWICH: Suwoman(ph).

Ms. BORODITSKY: Woman.

KRULWICH: And she assigned oos and sus to tables and chairs, arbitrarily. And after one day of learning this new language?

Ms. BORODITSKY: What we find is that just learning this kind of grammatical distinction in the lab is enough to induce some of the very same affects. KRULWICH: So if the word bridge, for example, in Gumbuzi, is a male word, oobridge(ph), will they begin assigning it dangerous, long, towering, strong and sturdy?

Ms. BORODITSKY: That's exactly what we see.

KRULWICH: And that just comes from the inner logic of the grammar of the language?

Ms. BORODITSKY: And in - you have no idea it's happening to you. You just think you're learning a way of talking but really, you're learning a whole way of seeing the world.

KRULWICH: But you know, I keep listening to you and I'm thinking about Shakespeare.

Ms. BORODITSKY: What do you mean?

KRULWICH: Well, if we went back to the fundamental question here, remember it was Shakespeare who said that what we call a thing does not matter, like with the rose thing. A rose?

Ms. BORODITSKY: That's right. Shakespeare had a hypothesis that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

KRULWICH: ?would smell as sweet, um-hum.

Ms. BORODITSKY: And actually, I've had students in a class of mine at MIT test out Shakespeare's hypothesis.

KRULWICH: How - what did they do?

Ms. BORODITSKY: Make two paper bags and you put a rose in each.

KRULWICH: And then I guess, with a magic marker, what you do is you mark one of the bags rose, and the other bag, though it also has roses inside, you label mowed grass, or something like that, and then you invite people to sniff each bag. They can't look; they just sniff. Ms. BORODITSKY: And then they have to rate how pleasant the smell is, how sweet the smell is and so on.

KRULWICH: And it turns out that a rose by another name, mowed grass, does not smell as sweet. People overwhelmingly said the bag marked rose smelled to them sweeter. So Shakespeare was wrong.

Ms. BORODITSKY: You can turn Shakespeare into an experiment.

KRULWICH: And these experiments suggest not only that the language you speak seems to change your experience of the world, it may even change, I don't know, the way you think.

Ms. BORODITSKY: Yeah, the way you think, the way you see the world, the way you live your life, all of those things.

KRULWICH: Lera Boroditsky teaches psychology at Stanford University in California.

I'm Robert Krulwich, NPR News, in New York.

Copyright © 2009 National Public Radio®. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio. This transcript is provided for personal, noncommercial use only, pursuant to our Terms of Use. Any other use requires NPR's prior permission. Visit our permissions page for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a contractor for NPR, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of NPR's programming is the audio.

The Power of Language By Stusan Stamberg NPR: Morning Edition October 21, 2003 7 min 46 sec http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1473161