DOES PE STILL MATTER? SOARING PRICES UNDERMINE VALUE OF VENERABLE YARDSTICK

Published: Saturday, March 11, 2000 Edition: Morning Final Section: Business Page: 1C

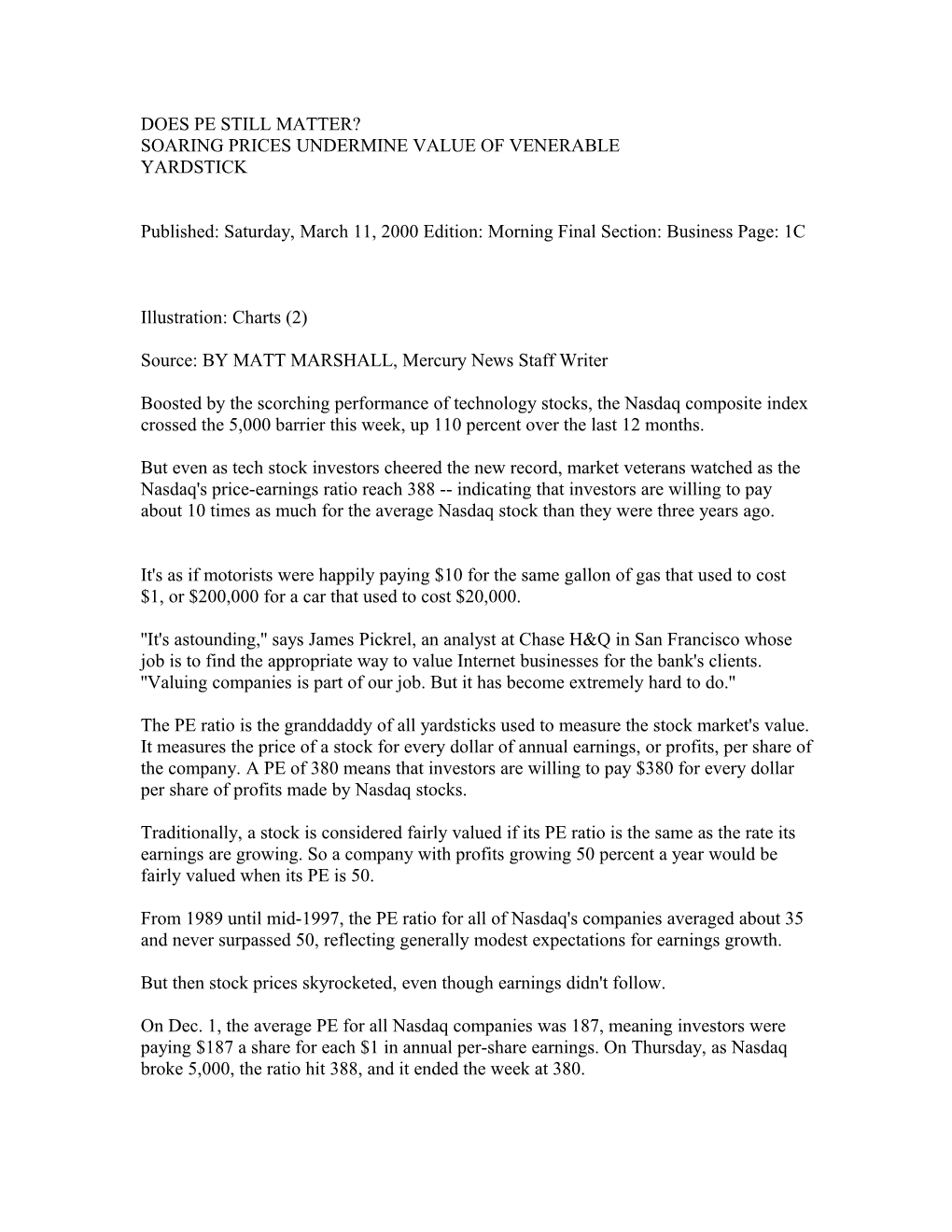

Illustration: Charts (2)

Source: BY MATT MARSHALL, Mercury News Staff Writer

Boosted by the scorching performance of technology stocks, the Nasdaq composite index crossed the 5,000 barrier this week, up 110 percent over the last 12 months.

But even as tech stock investors cheered the new record, market veterans watched as the Nasdaq's price-earnings ratio reach 388 -- indicating that investors are willing to pay about 10 times as much for the average Nasdaq stock than they were three years ago.

It's as if motorists were happily paying $10 for the same gallon of gas that used to cost $1, or $200,000 for a car that used to cost $20,000.

''It's astounding,'' says James Pickrel, an analyst at Chase H&Q in San Francisco whose job is to find the appropriate way to value Internet businesses for the bank's clients. ''Valuing companies is part of our job. But it has become extremely hard to do.''

The PE ratio is the granddaddy of all yardsticks used to measure the stock market's value. It measures the price of a stock for every dollar of annual earnings, or profits, per share of the company. A PE of 380 means that investors are willing to pay $380 for every dollar per share of profits made by Nasdaq stocks.

Traditionally, a stock is considered fairly valued if its PE ratio is the same as the rate its earnings are growing. So a company with profits growing 50 percent a year would be fairly valued when its PE is 50.

From 1989 until mid-1997, the PE ratio for all of Nasdaq's companies averaged about 35 and never surpassed 50, reflecting generally modest expectations for earnings growth.

But then stock prices skyrocketed, even though earnings didn't follow.

On Dec. 1, the average PE for all Nasdaq companies was 187, meaning investors were paying $187 a share for each $1 in annual per-share earnings. On Thursday, as Nasdaq broke 5,000, the ratio hit 388, and it ended the week at 380. Most of the rise in PEs has taken place in the technology sector. By contrast, the PE for the 30 blue chips of the Dow Jones Industrial Average is 27, just a bit higher than the historical median of 20.

So are tech-stock investors completely insane, foolishly paying more for the Amazon.coms and Red Hats than they will ever be worth? Or has something fundamentally changed in the marketplace, where many beloved dot-coms have no earnings and won't for many years?

Market experts are struggling to make sense of it all.

''The old model of valuing stocks isn't working anymore,'' said Steve Guo, senior quantitative analyst at Birinyi Associates in Connecticut. ''I wouldn't even try using price- per-earnings. Five years ago, it was a different story.''

End to fundamentals

Faced with such confusion, Guo said there is no point in searching for alternative ways to measure the value of a stock, once referred to as doing an analysis of a company's economic fundamentals. ''Right now, we're not doing any fundamental analysis,'' he said.

''How much weight should be given to PE? What does this all mean?'' asked Rusty Britt, a San Jose investor. ''That's a question I ask my stockbroker every time we get together.''

Without a benchmark like the PE to guide investing, many investors are searching for direction.

Some analysts have turned to a raft of other measurements, including some amusing ones, such as the ''price-to-story'' ratio or alternative PEs, like ''price-to-enthusiasm'' or ''price-to-eyeballs.''

The more conservative ones, however, have sought to reform the PE just enough to apply it to the Internet economy. The most conventional explanation for Nasdaq's stratospheric PE ratio is that Internet and other high-tech companies are more valuable than their losses or earnings might indicate because they are busy investing in their futures. If they spend now on advertising and other costs in order to boost their market share in the new Internet economy, they'll reap profits later, the theory goes.

Thus, some experts say the PE concept can be comfortably discarded.

In fact, Nasdaq's current PE is high partly because the market has more money-losing companies than it used to. The losses of these companies reduce the total earnings for the companies on Nasdaq and drive the PE ratio up. If you count only the profitable companies among the top 100 companies on Nasdaq, their PE was 78 at the beginning of the year, and has risen to more than 80 since then. This is still more than twice the historical median, but closer to earth than the PE for the whole Nasdaq market.

Highest in high tech

The highest PEs on Nasdaq are usually found among young high-tech companies. For example, an old-timer like chip maker Intel had a PE of 51 Friday. Yahoo, a Web portal, had a PE of 648. And MicroStrategy, which produces software for Internet companies, had a PE of 1,788.

Some market analysts argue that such high ratios simply aren't sustainable. They warn that the old PE ''rule of thumb'' is as basic as the law of gravity: what goes up, must come down.

If that's true and the PE of Nasdaq companies were to return to a more historical value like 38, it would mean a 90 percent drop in the value of the Nasdaq, wiping out $720 billion in investor wealth.

''We're definitely in a mania,'' said Paul Sonkin, a professor at Columbia University and a partner of the Hummingbird Value Fund in New York. ''And it definitely won't have a happy ending.''

Investors, meanwhile, are doing the best they can.

Britt views Time magazine's decision to choose Amazon.com's chairman, Jeff Bezos, as its ''Man of the Year'' as a scary sign that perception, rather than reality, is influencing the value of stocks.

She calls herself a ''conservative'' investor, and she wishes stocks would adhere to the old PE rule. Britt is buying up stock in companies like Johnson & Johnson and Merck, so- called Old Economy stocks that have lower PEs.

Still, she's reluctant to avoid technology entirely, so she is also buying shares in bigger, more stable tech companies like Lucent, Microsoft and Dell which, despite high PEs, seem to have a promising future.

Sticking with them

As much as they anguish about the soaring PEs, therefore, individual investors are themselves fueling their rise: They're holding the stocks even though they believe the high PEs indicate they're overvalued. Evelyn Meyer, of Saratoga, and a member of a stock club called ''A Step Ahead,'' said her group decided early on not to invest in companies with inflated PEs.

They do own technology stocks like Dell Computer, and Cisco Systems. But they invested when the PEs of those companies were a mere fraction of what they are now. Dell's PE hovered around 20 for years, but in mid-1997 began a steady climb to about 65 today. Likewise, Cisco's PE stayed at around 50 throughout the early and mid-1990s, but after 1998 soared to 152.

Although these PEs are still low by comparison to many dot-coms, they worry investors like Meyer. But she doesn't plan to sell.

After all, she said, ''Our return is quite admirable.''

And that, for many investors, is all that counts.

[RELATED STORY] HOW THE PE RATIO DEVELOPED BY MATT MARSHALL, Mercury News Staff Writer

The price-earnings ratio is one of a series of benchmarks developed after the Great Depression to measure the fair value of stocks.

Defined as the price of a stock for every dollar of annual earnings attributed to a share of that stock, PE arose from the assumption that investors bought a stock based on a company's underlying economic health.

The more profits a company made, the more investors should be willing to pay for the stock.

If a PE ratio itself began to rise, it meant investors were expecting more profits from the company in the future. If it fell, it showed that investors were losing confidence and thought the company would struggle in the future.

Though PE was used informally on Wall Street in the early 20th century, it was Benjamin Graham, a professor at Columbia University, who formalized the concept in his 1934 book, ''Security Analysis.''

Graham's work influenced a generation of investment gurus like Warren Buffett, Mario Gabelli, John Neff and Michael Price.

In recent years, however, the fast growth of many technology companies has persuaded investors to look beyond PE to other measures of value. Among them: (box) Price-to-revenues: First, analysts reasoned that the more sales that an Internet company had, the more likely that it was gaining market share in the new online economy. Profits could come later, but sales were seen as the most important measure of a company's future value. Thus, the price-to-revenues ratio became the measure du jour.

(box) Price-to-estimated-revenues: Like PE, price-to-revenues ratios have soared, a sign that investors were disregarding them. What really mattered, analysts decided, was a company's strategy, since even land-grabbing often doesn't produce any sales.

Thus, analysts concluded that estimated revenues for the following year was the important benchmark.

(box) EBITDA: In some sectors, the PE measure was altered to take into account an industry's special characteristics.

Large expenditures by semiconductor companies to build factories or telecommunications companies to string cables hurt earnings over a long period as they were slowly amortized on the company's books.

Analysts were willing to overlook such costs, believing that the company's cash flow from day-to-day operations was more important. To measure a company's cash flow, they came up with the so-called EBITDA, or earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization.

CHART: MERCURY NEWS

Nasdaq PE soars

Source: Nasdaq, Bloomberg News

CHART: MERCURY NEWS

PE SAMPLES

Here are some examples of the price-earnings ratios for Silicon Valley stocks that trade on Nasdaq.

COMPANY PE Ratio Yahoo 648

BroadVision 1,173

SDL 482

Artisan Components 835

Rambus 1,238

All PE ratios are calculated based on stock prices at Friday's close and current earnings.

Source: Bloomberg

.